Songs

Wearin 'o' the Green, The Rifles of the IRA

Battles

Battle of Yellow Ford

Tidbits

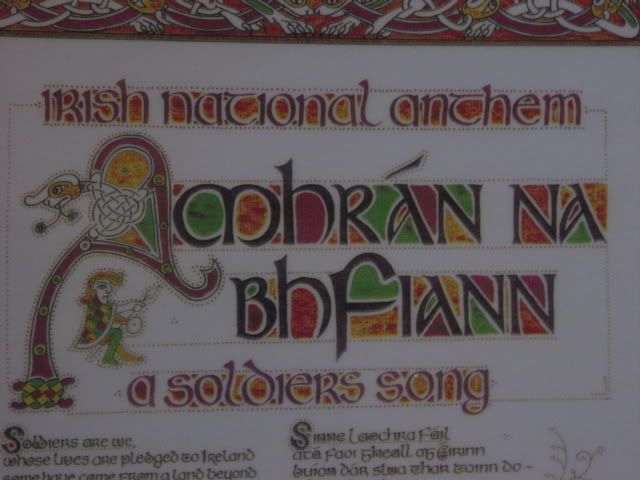

The O'Donnell Abu vs A Soldier's Song

Pictures

Irish Shillelagh, Drumoghill picture and stones, Irish Anthem Poster,

Meaning of the Name: Domhan is the Gaelic for 'world' and Dómhnall means 'world ruler'. Ó Dómhnaill = descendent of Dómhnall.

History Variations of the Name: (English)O'Donnell, O'Donell, O'Donel, (Gaelic)Ó Dómhnaill, Ó Dónaill

About the middle of the 18th cent. some immigrated to Spain and Austria, in which countries they played an important role. (General Leoopoldo O'Donnell, Spain, who brought Morocco under Spanish control. For this he and his descendants received the title, Duke de Tetuan)

General Leoopoldo O'Donnell

The most senior O'Donnell family today(according to the Chief Herald) is that of John O'Donnell (deceased), Blackrock, Co. Dublin, namely, Fr. Hugh O.F.M., Nuala and Siobhan. Next in seniority is Leopoldo O'Donnell, Duke of Tetuan, Madrid. The next in line live in Austria, Gabriel, Count O'Donell von Tyrconnell.

Without dwelling too much on ancient history, the popular myth of Donegal's traditional poverty must be laid to rest before we can deal with the present day.

The late medieval lordship of Tir Chonaill (Donegal) reached the height of its power during the years 1461 - 1555. The lords of Tir Chonaill became the dominant force in Gaelic Ireland for almost a century. The lordship itself was in close contact with many centres of the Renaissance in Europe. Focusing primarily on three lords or princes of Tir Chonaill - Aodh Ruadh, Aodh Dubh and Maghnus O'Domhnaill - who between them ruled from 1461 - 1533 in an almost unbroken line of direct succession, these three lords (father, son and grandson) are recorded in history as "Three of the most remarkable men ever produced in Co. Donegal".

Able and gifted, they have been described as the great soldier-statesmen of their respective generations in Gaelic Ireland.

The rise to power of the O'Donnells after 1461 shows remarkable leadership. At the height of their power, these lords of Tir Chonaill became immediate overlords of nine North-Western counties, their power being built on the great loyalty shown to them by the inhabitants of Tir Chonaill.

Tir Chonaill was certainly not a depressed economic region in late medieval times. It's natural resources were utilised by a relatively small population, concentrated in the fertile lowlands. The region was famous for its vast herds of cattle and flocks of sheep, as well as large unenclosed areas sewn with oats. The uplands and the rugged western coastlands were then largely uninhabited, providing the lowland inhabitants with valuable pastures, turf banks (fuel) , large woodlands and extensive reserves of wild game. Rivers and sheltered inlets were also a tremendous natural resource, giving salmon, eel, oyster and seal fisheries. Sheltered bays attracted large numbers of foreign merchants and fishermen (not much change there!) exploiting an immensely valuable salmon and herring fishery, which developed during the course of the early sixteenth century into one of the biggest of its kind in Europe.

On the continent, the lords of Tir Chonaill were famed for their wealth, increased by their skillful commercialism. While the Bretons and French supplied the O'Donnell's with wine, salt, iron, gunpowder and firearms in exchange for fish, tallow & hides, the Spanish too were important players. Hundreds of their fishing fleet were known to frequent the west coast. Not only did the Spaniards pay tribute of between a tenth and a sixth of their catch for protection while they fished, but they also paid for onshore facilities to cure their catch. Enterprises connected with the herring fishery were concentrated in the North-West, with O'Donnell ports such as Arranmore doing an extensive trade.

The pilgrim trade between the North-West of Ireland and the continent was another important form of contact between Renaissance Europe and Tir Chonaill. St. Patrick's Purgatory (Lough Derg) was one of the most exotic pilgrimage sites in western Europe. Many important visitors came to the site, not least Pers Yonge, Master of the Magdalen in London, who brought a letter from Aodh Dubh O'Domhnaill to Henry VIII in 1515, and the French knight who came via Scotland in 1516. Such was the hospitality received by this individual that he returned with artillery and royal soldiers from the king of Scotland, enabling Aodh Dubh to capture Sligo and three other castles. Pilgrims from the North-West in turn visited Santiago de Compostela in Spain, the holy site associated with St. James. Many of those were undoubtedly from Tir Chonaill, as Aodh Dubh in 1507 told James IV of Scotland that he had intended to visit Galicia himself, but had been otherwise advised.

Once there, Tir Chonaill pilgrims must have been impressed by the great Renaissance inspired Royal Hospice for Pilgrims built by King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella.

It is evident therefore that Tir Chonaill did not depend on southern England for its links with Renaissance Europe. Much more important was the contact with lowland Scotland, Brittany and Rome, which brought the region into direct touch with centres of humanist thought.

Donegal Castle

The main banquet room in Donegal Castle recently restored and now open to visitors in Donegal Town

Donegal Castle, by the banks of the river Eske, was built by Hugh Roe O'Donnell in 1474. His son - the legendary Red Hugh O'Donnell - fought bravely against the English in many a battle, one of which is commemorated in the song "O'Donnell Abu". Sadly, his last great battle was to be Kinsale in 1601 when his army marched non-stop from Donegal and were badly defeated. The tactics decided in the castle prior to the battle were to have significant ramifications for the country.

It is said that Red Hugh, aware of his imminent fate, destroyed the castle before leaving, "to prevent this fortress of the Gael becoming a fortress of the Gall". On capture, the English were able to fortify such castles and use them as a base to attack the Irish. However, this is what happened with the castle being granted to Captain Basil Brooke in 1611. He extended the manor house to the existing tower house and is indeed claimed to be the architect responsible for the layout of Donegal Town Centre.

After passing through several generations of Brookes before falling into decay in the 18th century, the then owner (the Earl of Arran) placed the castle in the guardianship of the Office of Public Works in 1898.

Only in recent times has the castle been restored, furnished throughout with Persian rugs and French tapestries. Writing about the castle's history, the author John M. Feehan goes as far as to suggest that the whole history of Ireland for three hundred years was decided within the castle walls before Kinsale. He recommends that we should "step up to them, touch, and say a silent prayer for the brave men who blundered so badly in those far-off days".

Then since the colour we must wear is England's cruel red,

Sure Ireland's sons will ne'er forget the blood that they have shed;

You may take the shamrock from your hand, and cast it in the sod,

But 'twill take root and flourish there, tho' underfoot 'tis trod.

When law can stop the blades of grass from growing as they grow,

And when the leaves in summertime their verdure dare not show,

Then I will change the colour that I wear in my caubeen;

But till that day, please God, I'll stick to wearin' o' the green.

But if at last our colour should be torn from Ireland's heart,

Her sons, with shame and sorrow, from the dear old isle will part;

I've heard whisper of a country that lies beyond the sea,

Where rich and poor stand equal in the light of freedom's day.

Oh, Erin! Must we leave you, driven by a tyrant's hand?

Must we ask a mother's blessing from a strange and distant land?

Where the cruel cross of England shall never more be seen,

And where, please God, we'll live and die still wearin' o' the green.

They burned their way through Munster and laid Leinster on the rack,

In Connaught and in Ulster marched the men of brown and black,

They shot down wives and children in their own heroic way,

And the Black and Tans like lightning ran from

The rifles of the IRA.

They hanged young Kevin Barry high, a lad of eighteen years,

Cork City's flames lit up the sky but our brave boys knew no fear.

The Cork brigade with hand grenades in ambush waiting lay,

And the Black and Tans like lightning ran from

The rifles of the IRA.

The Tans were caught, taken out and shot by the brave and valiant few,

Sean Treacy, Denny Lacey, and Tom Barry's gallant crew,

Though we're not free yet, we won't forget until our dying day,

How the Black and Tans like lightning ran from

The rifles of the IRA.

Nothing much else is recounted in the records for that year until mid-August when one of the greatest battles in Irish history took place - the Battle of the Yellow Ford, Cath Bhéal an Atha Buí.

Red Hugh leading his army

The English, during a time of 'peace and amity' had built a strong fortress north of Armagh, on the Blackwater. The three hundred choice soldiers garrisoning it often preyed on the locals for food. Finally, Hugh O'Neill with the help of Red Hugh O'Donnell decided to attack it and raze it to the ground. But being unsuccessful they abandoned their attack and returned to their homes. Later, O'Neill lay siege to it. The English, on learning of the plight of the garrison, assembled five thousand, both infantry and cavalry, well-armed troops to relieve the fort. O'Neill, on learning of their plans, invited O'Donnell to his aid. Red Hugh with his assembled troops, about 2,000 along with the same number of Connacht men and some Scots joined O'Neill before the English got there. The English marched from Dublin to Drogheda, from there to Dundalk, then to Newry and finally to Armagh. The Irish camped on the route they would take from Armagh to the fortress.

Finally, on the morning of the 10th of August(some records give the 14th) the English got up at dawn and "proceeded to clothe themselves with strange tunics of iron, and high-crested, shining helmets, and foreign shields of well-tempered, refined iron. They seized their wide-edged axes, smooth and bright, and their straight two-edged swords, and their long, singled-edged blades, and their loud-voiced shot-firing guns, so that it would be very hard for their leaders to recognise them if they were not known by their speech, owing to the array of shields, helmets and armour on them outside, hiding and covering their faces and their features, and to the quantity of arms also concealing them." Their captains under the supreme command of Henry Bagenal proceeded to arrange them in battle order and at last they marched to meet the Irish.

The Irish, according to Beatha Aodha Ruaidh Uí Dhomhnaill, marched to meet them. "Their weapons and dress were different, for the Irish did not wear armour like them, except a few, and they were unarmed in comparison with the English, but yet they had sufficient wide-bladed spears and broad-grey lances with strong handles of good ash. They had straight two-edged swords and slender flashing axes for hewing down champions. There were neither rings nor plates on them, as there were on the axes of the English. The implements for shooting which they had were darts of carved wood and powerful bows, with sharp-pointed arrows, and the English generally had quick-firing guns."

From these descriptions we see that the English were superior in arms. However, they were inferior in numbers. O'Neill had chosen the field well and had made some preparations. It was a narrow strip of ground with the River Callan to their(Irish) right and a bog and wood to the left. O'Neill had trenches dug and covered over with branches and heather in front of the Irish line. He and the Irish chiefs then proceed to exhort and instruct their men in preparation. "…be not feared or frightened by the English on account of their strange engines, their unusual armour and arms, and the thundering sound of their trumpets and tabours and war-cries, and of their own great numbers, for it is absolutely certain that they shall be routed in this day's fight." One of O'Donnell's bards who had accompanied them, recounted a prophecy made by an Irish saint which promised victory to an O'Neill fighting at a place called 'Béal an Átha Buí.'

All this had its affect. By the time the English arrived the Irish were really roused and ready for battle. Their spirits were further raised on seeing the English cavalry charging towards them and suddenly disappearing into the ground. Realising their greatest danger was from the English guns, the Irish, quickly closed in on the English leaving no room to use their muskets. The English right flank was attacked by O'Donnell and Maguire who had been hiding in the wood. Thus the English were pushed together so tightly that only those on the outside could fight. Furthermore, the English suffered two strokes of bad luck. Firstly, all their gunpowder exploded killing many and throwing the whole centre of the army into confusion. According to Lughaidh Ó Clérigh, "… all round was one mass of dark, black fog for a while after, so that it was not easy for any one to recognise a man of his own people from one of his enemies." Secondly, several of the English leaders, including Henry Bagenal, were killed and this added to the confusion. Henry's sister, Mabel, had sometime previously been married to Hugh O'Neill much against Henry's wishes. Though the English fought gallantly, nothing seemed to be in their favour and finally they fled towards Armagh having sustained the greatest defeat that had befallen them since the first Norman set foot on Irish soil in 1169 AD.

The Irish pursued them all the way to the city and then returned to the battlefield where they beheaded those severely wounded and collected the booty. The Irish then lay siege to Armagh. After three days the English asked to parley. Finally it was agreed that all English could go free provided those in the fortress departed leaving all their possessions behind. It is estimated that the English lost between 2,500 and 3,000 men including some of their best officers and nobles while the Irish losses are put at something around 500.

News of the battle infuriated Queen Elizabeth so much she complained that, "naught but news of fresh losses and calamities," from Ireland reached her ears. Morale was now at an all-time high among the Irish and many more joined the Irish confederacy while much of Munster rose in rebellion.

O'Donnell, after resting his men, turned his attention to Connacht once again. For thirteen years the English held Ballymote Castle. This was a strong fortress with an English garrison which had withstood many unsuccessful attacks from the Irish. Then, one day by some stroke of luck, the local Clann Donncha of Corran took it and held it. It was a great embarrassment to Sir Conyers Clifford, Governor of Connacht, that this strong strategic fortress should slip away so easily from the English. He offered a handsome reward for its return. On hearing of these developments, Red Hugh, immediately, set off and on arrival there besieged the castle. He tried all means to gain possession of the castle, force, threats, begging, pleading, promises etc. He finally ended up buying it for four hundred pounds and three hundred cows. The three hundred cows he rounded up in the next few days from those in the neighbourhood not loyal to him. It is possible, though not stated in the records, that he acquired some of the money in like manner. The records do state that "nine score pounds of that money" came from Seán Óg O Doherty. "The town was given over to O Domhnaill then, and he remained there afterwards." Red Hugh seems to have established Ballymote Castle as his military base from then on.

This all happened in the month of September and from then till the end of the year O'Donnell kept his men busy attacking and taking cattle and booty from all those on the English side, "and his army took the prey with them without strife or skirmish till they came by slow marches to Ballymote. Never before was the spoil of enemy's cattle collected the like or equal to it in that place since it was first built. Thereafter O Domhnaill's army go to their homes." And thus ended 1598.

There is a little place in Ireland that my granda always went to called Drumoghill. We have a piece of stone from Drumoghill, along with a beautiful photo. Way back when, the English forbade the Irish to go to Mass, so the Irish held secret Mass at Drumoghill. It's a highly sacred place, my granda says. Along with the stone and photo we have a laminated copy of the Irish national anthem -- in English and Irish Gaelic.