Book Reviews:

Fantasy and Science Fiction

It’s always difficult to find good fantasy and

science fiction. Much of it, after all, is utter junk. So I thought it was

worth the time and effort to create a page suggesting good authors, and good

books, for intelligent and discriminating readers who are disinterested in the

typical fare which science fiction and fantasy authors churn out year after

year. Be forewarned, however, that this page is oh so very under construction. There are only a few reviews written so far, but I've put up a skeleton of the way the final page should look. Keep checking back until it's done!

To begin, here is a list of fantasy and science

fiction authors, ranked by my evaluation of their literary merit. What is

“literary merit,” you ask? Why, it is simplicity itself: my evaluation of an

author’s “literary merit” is a composite of the volume of good material

produced by an author, and the ratio of good to bad works which an author

provides. Jack Vance clearly tops the list with countless stories written over

the course of eight decades, all of which I personally evaluate as being, at

the very least, worth the read. Bram Stoker takes last place, with half of one

book being worth reading. I recommend that you read anything you can get your

hands on from the first several authors. Once you get more than halfway down

the list, I’d only read specific titles, because while some of these are quite

good, much of their work is a waste of time.

Favorite authors, from the most glorious to the most humble:

Jack Vance: The penultimate grandmaster of science fiction

Paula Volsky: An excellent historical

fantasy author

Lloyd Alexander: The best author of children’s fantasy to date

Robert E. Howard: CONAN.

H. P. Lovecraft: The master of horror

Robert Heinlein: His sci-fi showcases wonderfully developed sociological and political ideas

Edgar Rice Burroughs: Great romps through science fantasy adventure

Frank Herbert: Epic science fiction

Moorcock, Michael: Fantasy and science fiction

Andre Norton: Fantasy author

Sheri S. Tepper: Science fiction author

Howard Pyle: Personally illustrated

historical fiction for children

Patricia Ann McKillip: Fantasy Author

J. R. R. Tolkien: Epic fantasy author, poet, and linguist

Williams, Michael: Fantasy author

Bram Stoker: DRACULA.

And now, for the reviews. I’ll be filling this

section up as time goes on; here are the entries I’ve finished so far. Scroll

through the rest of this page, where books are sorted by author, or click the

links below, which are sorted by title, to skip to a specific book.

Crystal Gryphon, by Norton

Gates of Twilight, by Volsky

Grand Ellipse, by Volsky

Illusion, by Volsky

Lord of the Rings, by J. R. R. Tolkien

Prydain Cycle, by Alexander

Wolf of Winter, by Volsky

Alexander, Lloyd

| |

The Prydain Cycle

Lloyd Alexander's Prydain books are probably the most difficult to analyze and comment on - it is tempting to simply say, "these are the best books I have ever read," but this does little to describe the source of their inspiration and enchantment. The extended story works so well as unified and integrated literature that picking apart the many themes and aspects of these books to understand why they work is not at all a simple task.

All five books, The Book of Three, The Black Cauldron, The Castle of Llyr, Taran Wanderer, and The High King are written for children, telling the story of a young boy's adventures and growth into adulthood. But the themes are universal and timeless, and the books can easily be read and appreciated by those of all ages - as evidenced by adult websites devoted to Prydain, such as The Prydain Guide or Daughter of the Sea - as well as my own review here, written for adults.

|

To provide some background, Lloyd Alexander's Prydain Cycle is five books of epic fantasy for children which draws some of its charm from Welsh ledgends - the map of Prydain shows traces of the geography of Wales, and many famous heroes make an appearance, such as Gwydion. In this much, Prydain is a Welsh analogue to Middle Earth, which borrowed names and ideas from Scandinavian legendry. Prydain has a more exotic flavor, however, as the spellings are thickly Welsh - for example, the characters of Fflewddur the bard and princess Eilonwy play important roles throughout the story. (The appeal of these names will likely be lost of most younger readers, although their strangeness doesn't detract from the story - when I read his books around the age of ten, in my mind I simply glossed over the actual spelling of the names and places and changed them into more familiar forms, turning "Achren" into "Archen" and "Eilonwy" into "Ellenwy.")

One of the most important, and most successful, aspects of the Prydain books is their humor. Some of this is subtle enough that the epic fantasy aspects of the tale might drown it out for younger readers, but it is readily apparent to older readers:

On the little farm, while Taran and Coll saw to the plowing, sowing, weeding, reaping, and all the other tasks of husbandry, Dallben undertook the meditating, an occupation so exhausting he could accomplish it only by lying down and closing his eyes.

The great challenge for any fantasy or science fiction author is to create a world that draws the reader in and prevents him from perpetually thinking to himself how the events are unreal and impossible, and by developing more sides to a tale beyond the merely adventurous, an author can lend more credence to his world. Many fantasy novels lack developments except those in a serious direction, and they end up seeming flat and dreamy because of it. Humor should never be far from good fantasy.

|

Another way Lloyd is able to bring color and a feeling of solidity to his stories is by showing us his world of Prydain from the ground up. We learn about the world through the eyes of Taran, a child, and details of blacksmithing, animal husbandry, agriculture, and forestry abound. Lloyd also has Taran touring the countryside later in life, where he acquaints himself well with ordinary folk who have probably never held a weapon or traveled more than half a day's journey from home, and Alexander turns their simple lives as weavers, potters, or smiths into adventures in and of themselves.

After having reread the first book in the series, The Book of Three, what struck me the most throughout the tale was not the action or the plot, because, at times, Lloyd glosses over this. He does an excellent job with dramatic scenes ("No, I will not slay you; you shall come to wish I had, and beg the mercy of a sword!") but as an adult, it is obvious that what Alexander really wants to convey is the sense of struggling under responsibilities, resolving through moral dilemmas, and asking questions of what it means to do the right thing. While the Prydain Cycle can be read as epic fantasy, it is more a story about the journey into manhood, using the fantasy world of Prydain as a backdrop.

Also surprising is the way in which Alexander is able to present a world with very simple, clear cut definitions of good and evil, and at the same time grant it the depth it needs to make it ring true. Many of the heroes have moral failings, many of them quite mundane (they tend to bicker over trivialities, just like real people do), and later on in the series, villains can also show complexity. The themes of sacrifice, trust, and cameraderie come through very honestly, without seemingly self consciousness or cynically adult, and likewise without seeming simple or childishly monodimensional. Quite simply, if you let it, Alexander's writing can do more than merely entertain, or offer food for thought - it can change the way you feel about the world.

|

|

|

But the unforgettable characters are what truly make Lloyd Alexander's Prydain books so touching: Eilonwy, an impetuous chatterbox, Flewddur, a bard who never quite made it through training and can't seem to stop "exaggerating the truth" for dramatic effect, Prince Rhun, guileless and hopelessly clumsy, Achren, a beautiful but scheming witch given to vicious lapses of temper... the colorful inhabitants of Prydain with their signiture mannerisms make the story come alive in a way that not even the most sophisticated prose ever could.

In the end, the simple style of Alexander's writing serves as a strong point, because it makes it accessible to all readers, whether they speak English as a second language, or are children still learning to read, or even if they are ordinary adults with learning disabilities. The themes and writing style are straightforward enough to appeal to less accomplished readers, but there is enough depth to hold the attention of even the most jaded fantasy reader. Anyone who likes fantasy, even a little bit, should set aside the time for these books.

The Westmark Trilogy

The cat who wished to be a man

Burroughs, Edgar Rice

Robert Heinlein

Friday

Door into Summer

Glory Road

Job: A comedy of justice

For us, the living

Herbert, Frank

Dune

Howard, Robert

E.

Norton, Andre

If I had read any one of her other books before The Crystal Gryphon, I would never have given her writing a second glance. As a youth, I tried on numerous occasions to read through her other books, but each and every one I have come across - with the notable exception of The Crystal Gryphon, is terrible. There is simply no avoiding it: most of Andre Norton's fiction is disappointingly awful. This should not blot out the one shining star which she did write, however.

| |

The Crystal Gryphon

This book employs an unusual and very effective literary device - it is written in double first person. The events which transpire are seen separately through the eyes of Kerovan of Ulmsdale, and his bride by arranged marriage, Joisan of Ithkrypt. This technique works very well with the narrative quality of the story; Norton's characters do not describe events in great detail, giving only snippets of conversation and description throughout the story, as though these are the half-remembered details of a long story half-forgotten with time. While sometimes, especially earlier on, Norton's writing is more vague than would have been demanded by the constraints of realism, all in all the effect is well done, and renders the story far more believeable than most first person accounts.

The Crystal Gryphon also presents a wonderfully developed medieval world, which is organized in a fashion very like that which we might expect of a genuine society of that age. Word is passed only very slowly and without great accuracy from one kingdom to the next, gender roles are flexible but deeply ingrained, arranged marriage is the rule among the aristocracy, plague and famine are always around the corner, and the turning of the seasons figures importantly in everyday life.

|

If The Crystal Gryphon has a weakness, it is that its characters could have been more inspiring. Kerovan is a reasonably interesting fellow, at least, and a few other incidental characters are quite charming, such as Dame Math, the Norton equivalent of a nun, and Lord Imgry, an icy war leader. But Joisan is too flat as a main character, and what little development she does possess shows her as nothing more than a good little girl - robotic, a trifle slow witted, and deeply boring. Only towards the end, when she finally meets her husband-to-be, does she begin to develop in an interesting way; it is as though Joisan awakens halfway through the book into the person she is meant to be. (Possibly this transformation was purposeful on Norton's part, though it seems more a coincidence of insufficient authorial editing than a plot device or hidden message of some sort.)

Really, it is the end of the book which saves The Crystal Gryphon from mediocrity, because here, Norton increases the level of detail to match the drama and intensity of the plot, and is even able to give the readers two accounts of the same event, each one working in subtle details left out by the other, and allowing the readers to derive a deep understanding of both main characters, Kerovan and Joisan.

Overall, this book is highly respectable for its plot, its background, its subtext, and its style - a style Norton brings to her other works without success. For many years, The Crystal Gryphon was my favorite book of all time. In reading it again as an adult, however, and comparing it to other writings, I have to admit that while it really is a wonderful piece, it lacks a certain color or dramatic flair - and it is rather lonely. The sequel, Gryphon in Glory is worth reading, but not as good, and the third book in the trilogy, Gryphon's Eyrie is utterly hopeless. Fortunately, The Crystal Gryphon tells a complete story which is capable of standing on its own as a great work of fantasy.

Pyle, Howard

Otto of the Silver Hand

Stoker, Bram

Dracula

Tepper, Sherri S.

Grass

Tolkien, J. R. R.

The Lord of the Rings

If you’re reading this review, very likely it isn’t because you’ve never heard of The Lord of the Rings and are curious as to whether you’d like it or not. The widespread popularity of Tolkien is so great that multiple movies have been made based on his books; he is often cited as having started the entire fantasy genre. So my intention here isn’t to convince readers why they should read his books, but rather, to explain why those who have read his books should reconsider their opinion of his work.

To begin with, Tolkien’s writings were highly

derivative of old Germanic legends, so strongly that even the most cursory

investigation into Tolkien’s works will reveal that they were in no wise

creations of his fertile imagination. (Unlike the many languages he invented,

which were quite creative.) To say that he plagiarized his work would be

extreme, but the debt he owes to old Norse myth is great. “Middle Earth” is

merely the English translation of the Norse “Midgard,” the name “Gandalf” was

taken directly from old myth, and countless other plot devices, themes, and

creatures in Tolkien’s writing are lifted from Germanic mythology.

This by itself is not a bad thing, and in fact there

is much to be said for developing an established genre, but the question then

becomes, not whether his world and his ideas were creative, but whether he

executed well the creative ideas of those who came before him. And an honest

evaluation of his books finds that, clearly, he did not.

Tolkien’s interpretation of old myths has many shortcomings: his elves are syrup and saccharine, flat cartoons without weaknesses, creatures of elegance and beauty and strength and intelligence and refinement who dance lightly across cords and fashion unbelievably wonderful food (try not to think about Twinkies when reading his descriptions of lembas wafers) and who need not even sleep as mere mortals do. With the possible exception of Boromir, his heroes are weakly developed, utterly lacking in autonomous philosophical, political, or aesthetic opinions; with the possible exception of Saruman, his villains are worse, from the faceless orcs to the Dark Lord whom we never see but are assured is wholly evil. And his incidental characters are, if at all memorable, merely ridiculous or annoying (such as Tom Bombadil).

Throughout the entire Lord of the Rings trilogy, the action flows sluggishly, bogged down as it is by the trivial details of mealtimes, bugs, rain, and endless hours of travel. The dialogue is fairly good, but Tolkien can’t seem to go forty pages without burdening the reader with several lines of mediocre poetry or tuneless song. The writing is bland, the messages (power corrupts, nature is good) are flat and undeveloped, and the drama is weak. And while the plot itself could have been compelling—the least of the races, the hobbits (genuinely of his own creation) must penetrate Mordor by stealth and destroy the heart of the dark lord’s power by casting it into the cracks of Doom—the passion of the tale breaks down after its first third.

The Fellowship of the Ring gives us the surprising

disappearance of Bilbo, the dark tale of Gandalf and Frodo’s growing

realization of the evil which is taking hold of him through his association

with the ring, narrow escapes from the Black Riders, a tense meeting with

Strider and flight from the Prancing Pony, a dry yet interesting encounter with

barrow wights, a battle on Weathertop, and finally the dramatic escape to

Rivendell. The pace slows, here, but Tolkien uses the space in order to

continue developing the reader’s understanding of the storyline, and then

before too long, the adventurers reach the gates to Moria, with an interesting

password and the lurking Watcher which guards them. Then the battle with the

orcs, the disturbing scrawl of the dwarven diary, the appearance of the

terrible Balrog, and Gandalf’s final injunction—“Fly, you fools!” The book

begins to lose its rhythm after that point, but it manages to hold its own

though the woods and until the party is broken up by Saruman’s orcs, Boromir’s

treachery, and Frodo’s escape with Sam.

Yet the remaining chapters after The Fellowship of

the Ring are simply tedious. For a hundred pages, the readers are dragged along through pointless journeying, interrupted when Gandalf is capriciously

resurrected—a move which completely erases not only the power of his sacrifice

for Frodo’s quest, but which robs Tolkien of his ability to frighten his

readers in the future. Here, after all, is an author who always ensures that

things work out for the best, and whatever “danger” the heroes may experience

later, they are sure to come through it alive. And, in fact, they do.

It is mildly interesting to see Gandalf speak of his

travails, to see the discovery of the Palantir, and to watch events in Isengard

pan out, but in all of two hundred and fifty more pages in The Two Towers, the only glimpse of the engrossing heights of The Fellowship of the Ring come with the battle against Shelob.

The Return of the King is still worse; the Black

Riders were easily the most compelling aspect of Tolkien’s story, but now the

charm of the Riders from the Fellowship is lost, and they are transformed from

the snuffling, skulking riders into the dry, colorless Nazgul. The battle for

Minas Tirith is endless tedium, as is the final leg of the journey to Mount

Doom. And Tolkien’s sketchy writing at the end prevents the potential of the

final scene at Mount Doom, when Frodo forsakes his quest, and Gollum severs his

finger to fall with the ring into the fires of Doom, from ever being realized.

The reader is given two and a half pages, and no more, for the three scenes

which describe Frodo’s betrayal, Sauron’s realization of his own peril, and the

final struggle between Gollum and Frodo. Being few in number, these lines

should at least have shown Tolkien’s best writing, for what author doesn’t read

and reread his favorite passages to himself as he goes? Not Tolkien, it seems,

for the brief climax is as bland as everything he writes. Even the Nazgul, whom

we are supposed to dread and hold in awe and who could indeed have been truly

inspiring, are brought back to our attention and then casually obliterated in

so many words: “the Nazgul came, shooting like flaming bolts, as caught in the

fiery ruin of hill and sky they crackled, withered, and went out.”

At the very end of the tale, the scouring of the

Shire does give the reader something to wind down with, and Tolkien wraps up

his tale fairly well. If The Lord of the Rings had been the epic

masterwork which it promised to be, and which it is erroneously hailed as

being, these last chapters would have served quite nicely. But as it is, they

are merely that many more spoonfuls of humorless tedium to finish off a bowl of literary porridge.

Ultimately, this trilogy is not a truly bad work, but it falls far short of what it attempts to achieve. And while Tolkien is not an incapable author—The Hobbit was a far more charming work which is sadly forgotten beside The Lord of the Rings—the names of science fiction and fantasy authors surpassing Tolkien are many indeed. Readers who love his Lord of the Rings would do well to pick up virtually any other author named in this page, and not look back. But if I had to give one name for a fantasy writer who does everything Tolkien does, but successfully, it is Lloyd Alexander. Anyone insisting that Tolkien is the penultimate author of epic fantasy should read Alexander’s Prydain books, which are executed with more imagination, better style, more creativity, more depth, and better drama than Tolkien was ever able to supply.

Vance, Jack

Alastor

Araminta Station

Demon Princes 1-5

| |

Night Lamp

|

|

Planet of Adventure

Volsky, Paula

Paula Volsky is one of the few authors who manages to make almost every book a worthwhile read, and her work is highly recommended. Her novels are set in a sort of fantasy-Earth, with colorful renditions of Arabia, Eastern and Western Europe, and Africa. Probably the best book to introduce her world is her recent work, The Grand Ellipse, although she has other books which are better overall.

| |

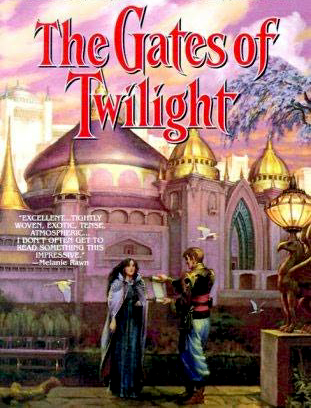

The Gates of Twilight

Volsky’s best novel is probably The Gates of Twilight, which takes place in something that might have been the Middle East in more mundane circumstances. In this novel, Volsky gives us a likable hero, a compelling heroine, a fascinating description of an eastern society oppressed by western imperials (along with the usual indictment of imperialism we might expect), weird religious cults, and military outposts. But most importantly, she manages to accomplish something in Gates of Twilight that neither Robert E. Howard nor H. P. Lovecraft ever quite managed—to develop cosmic villains which can interact with mortals in a way which allows for not only a deep plot but a genuine struggle. Howard always defeats his denizens of darkness too easily in order to showcase Conan’s heroism, and Lovecraft always makes his heroes feeble and helpless to showcase the awful might of the crawling chaos from beyond, and while in both cases this serves to achieve the author’s goals, it is done at the expense of a true struggle. It is difficult to explain why Volsky is able to give both a meaningful plot and preserve the remoteness, power, and alienness of the outer beings without giving it away, but readers are strongly encouraged to find out for themselves.

|

Illusion

If Gates of Twilight was Volsky's best book, then Illusion is probably her worst. Of course, fans of her work may still find it worth a look, especially female fans, given that the main character is a waif-like princess. But the book is really just revolutionary France with fantastic trappings. Unfortunately, the fantasy aspects, rather than breathing new life into the historical tale, render it silly. The beginning and end, however, which are less to do with the revolution and have more genuine fantasy to them, are much more interesting.

The Wolf of Winter

The Wolf of Winter is a slow book, and in many ways it lacks the charm of Volsky's other writings because it is so bleak. However, if nothing else this does help to develop the cold, barrenness of the pseudo-Russian landscape. Her characters are few, and their lives are isolated and lonely, but the villain is a brilliant masterpiece, an ostracized genius whose calm intelligence and undeserved suffering invokes sympathy, and he draws the reader into his growing depravity in a way few villains can.

The Grand Ellipse

While not her best work, The Grand Ellipse is in many ways Volsky's most interesting and most thought provoking. There is certainly a great deal to this work that is noteworthy, if not for its merit, then for its weakness. (And, if you find other reviews of this book, you may note that many are very positive while others are very negative, for some of the reasons detailed here.)

The downside to this book is that the story ends up being shallow and poorly developed, even though it is extremely long. Because of its “Around the world in 80 days” format, plots are constantly opened but seldom resolved—there are dozens of characters who are difficult to name and remember, and the main character, Luzelle, is perpetually forced to race away before genuinely dealing with anything. Some aspects are also laughably silly, such as her ridiculously petty father who insults her endlessly for being attractive at the start of the book, and who is never seen again after the first few pages. The book is rather long, and could have used some trimming and revision.

But in many ways, The Grand Ellipse is quite good. It is able to deliver a very entertaining read for over 600 pages, which is wonderful for a bibliophile who enjoys her style. While the plot may be somewhat lacking, the descriptions are vivid, the cultures fascinating, and the means of traveling through the various countries are always varied and interesting. There is also a well developed, yet understated, sense of romance which traces its way through the book, as well as a sprinkling of humor—an important spice which is often absent from fantasy novels. So the book is a modest success even if viewed purely as entertainment.

But best aspect to The Grand Ellipse is the way in which Volsky departs from modern stereotypes - this takes what might otherwise have been cheap entertainment and turned it into something which can be viewed as actual literature. Paula Volsky’s liberal leanings are always clear throughout her work, and never more clearly than in this book, but she does an excellent job of recasting political philosophies in a way which allows the reader to see them in a more ambiguous light.

The heroine, Luzelle, carries Volsky’s liberal attitudes—and ultimately the attitudes of all the modern world—quite proudly. She is in many ways ahead of her time, and readers might expect that she would display a sort of cultural sophistication and emotional understanding missing from her parochial contemporaries. Yet Luzelle is ultimately revealed throughout the novel as a reckless, thoughtless, helpless female, while her husband Girays, initially the rigid, heartless conservative, is revealed as a capable, competent, and caring man. (Luzelle’s growth and ultimate realization of her own petulant behavior help to give the book its depth—the main character isn’t simply a heroine, but, in a way, becomes one after her adventures.) Luzelle repeatedly insists that members of other cultures not be dismissed as inferior or untrustworthy, yet the narrative throughout the book depicts them as ugly, or fat, or grasping, or lewd, or stupid, or simply primitive—often all at once. And the most sympathetic and heroic character of all is one Karlsler Stornzoff, who is the Volsky equivalent of a National Socialist. While the book can be read as a straightforward attack on 19th century philosophies, it ends up doing a great deal to cast them in an understandable light. The harsh view of non-European cultures which Volsky offers, and the uncertain interpretations the reader is given towards the dominant imperialist powers, allow for a great deal of depth and an intriguing alternative look at our own world which Volsky may not have intended to include. Readers who really sit down and think about it might be left wondering if it isn’t moderners who are parochial and narrow minded to blithely insist that Victorian standards were completely bigoted and ignorant and that all cultures are of equal merit. In a day and age where political correctness infuses the entire media, where non-Westerners are boringly, predictably, mature and enlightened, and where blond-haired, blue-eyed Germans are boringly, predictably, villains, The Grand Ellipse provides a refreshing change.

Moorcock, Michael

Elric of Melnibone

Dancers at the End of Time, The Hollow Lands, The End of All Songs

Williams, Michael

Weasel’s Luck

I like getting feedback; please send your comments to harkenbane@juno.com.

Back