Jonesy (John Goodman) at work.

|

||

|

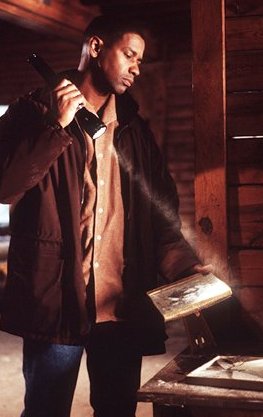

Hobbes (Denzel Washington) and

Jonesy (John Goodman) at work. |

|

|

| Director: Gregory Hoblit | Screenplay: Nicholas Kazan | ||

| Producers: Charles Roven and Dawn Steel | Editor: Lawrence Jordan | ||

| Director of Photography: Newton Thomas Sigel | Production Design: Terence Marsh | ||

| Costume Design: Colleen Atwood | Music: Tan Dun |

| John Hobbes: Denzel Washington | Gretta Milano: Embeth Davidtz | ||

| Jonesy: John Goodman | Lou: James Gandolfini | ||

| Lt. Stanton: Donald Sutherland | Edgar Reese: Elias Koteas |

| by T. Larry Verburg |

|

Where to begin? The plot of this film demands, no, requires, a willing suspension of disbelief. It appears that angels are very real entities—and so are fallen angels. The title of the film thus betrays its content. The very silly premise of the film is that fallen angles are out to get God in a big way. And what more diabolical way to reap vengeance on Him than to just generally screw up, play mind games with, and, yes, to wantonly kill these creatures made in His image? If we are to believe this humorless film, Beelzebub, and others of his ilk, are behind all of the serial killings plaguing today’s society. But evil is fallible. Because these demons are still somehow "spiritual" beings, they must inhabit a human (or animal) "host." Once a demon enters its host, the host does the demon’s bidding with the total loyalty and obedience of a robot. But the relationship is anything but beneficial to the host. One of the favorite games of the demons is to see how many serial killings they can chalk up before their human host is shot, gassed, hypodermically syringed, or electrocuted into non-existence. When their human host gives up the ghost, they just peacefully waft away on the breeze to land on some other poor unsuspecting human (or animal). Denzel Washington stars as John Hobbes, a Philadelphia homicide detective who has somehow ticked off Azazel, the head fallen angel. In fact, getting Hobbes becomes, for no apparent reason, the demon’s special project. Apparently, life in Demonsville is real dull. Anyway, Hobbes becomes the pet whipping boy of Azazel, who generally makes a pest of himself. In rapid succession, Azazel has Hobbes suspended from the police force, suspected of murder, and finally hounded by the police—an outlaw hopelessly on the run.

|

|

To top it all off, Azazel murders Hobbes's brother (Gabriel Casseus) with a hypodermic syringe filled with poison, the choix du jour of self-respecting demons everywhere. (No, Azazel's latest host, Edgar Reese [Elias Koteas], was not put to death by lethal injection, that would be too logical.) Luckily, Hobbes doesn't have a pet dog or we would likely see the critter skewered en brochette, or wind up like the rabbit in Fatal Attraction. All of this mumbo-jumbo is fueled by the daughter of a homicide detective who was likewise harassed 30 years earlier and ended up a suicide. The daughter, Gretta Milano (Embeth Davidtz), is a professor of religion, no less. Ms. Milano is, no doubt, too serious about her work and needs to lighten up a little. She ultimately succumbs to Hobbes charms and befriends Washington and his young nephew (now orphaned by the brother's murder) who are on the run at this point in the film. (Shades of Hitchcock's The Wrong Man.) |

|

||

|

Hobbes (Denzel Washington) finds

a book on demonology. |

|

Azazel and the other demons have one pretty nifty trick that makes them all but invincible—they can hop from one host to another with all the happy facility of fleas. Merely touching someone on the shoulder, or shaking hands, allows the demon to exchange hosts faster than Donald Trump or Jay Leno can change automobiles. Why, it's like a fun game of tag—You're it! Only the first prize for the luckless host is a kick in the seat of the pants.

|

|

Well, if there are demons (fallen angels to be exact), then does the film make the corollary statement that God exists? Note quite. The only serious religious questions raised in the film are answered in the negative. Hobbes, for example, has lost his faith, or what little he had, through years as a big city police officer. He has come to no great revelation about earth, life, death, God, or any other teleological question. Nor is there any great epiphany for Hobbes at the end of the film. At first, Hobbes merely looks with quiet skepticism and a slight patronage on those who question his spiritual beliefs—namely the professor of religion (the love interest in the film) and Azazel, who speaks through his various human hosts. There is not much dialogue in these encounters because the demon invariably begins speaking in tongues, or rather ancient Aramaic, the language of the historical Jesus. By the way, as Hobbes remarks in the film, "Azazel" is in the dictionary—I looked. Webster defines Azazel as "an evil spirit of the wilderness to which a scapegoat was sent by the ancient Hebrews in a ritual of atonement." (Azazel was also the standard-bearer of the rebel angels in Milton’s Paradise Lost.) Apparently, since there are no more ancient Hebrews practicing this particular ritual, and no more scapegoats, Azazel must improvise. The film, directed by Gregory Hoblit (Primal Fear, 1996), seems to say that all of the villains and the nameless evil lurking out there, just beyond our peripheral vision, are caused by the machinations and conscious purpose of the demon brigade. This happy thought releases us—who, let it be understood, are created in God’s image and have freedom of choice—from any blame for the miserable state of human affairs. This idea sounds suspiciously like the theme of Millennium, that most downbeat of all television shows (now, sadly off the tube). Why does it always seem to be Winter in any television show or film concerned with serious evil? Perhaps they are all filmed in Canada where it is always winter. The premise of all these new age shenanigans is, I guess, to somehow equate evil, the coming of the year 2001, the rising crime rate, and El Niño with the devil and to thereby stimulate religion. Does this renewed interest in the diabolical prophesy a return to orthodox religion or to a higher spiritual awareness? The movie does place a certain pathetic spin on Flip Wilson’s line, "The devil made me do it!" But, if all this Biblical posturing is true, where is Gabriel and his heavenly choir? Shouldn’t he arrive at the head of a cherubic cavalry riding swift and hard to save Hobbes, his nephew, and the professor of religion—not to mention all the rest of creation—from these evil entities? Some of the special effects would be interesting if they weren’t so hackneyed through overuse: the protagonists seen from the vantage point of the demon (weird camera angle and odd color tint), strange words written on mirrors, letters written on a string of dead bodies to form a word ("apocalypse"). There is one really nice image, however, where Hobbes and Gretta Milano are discussing Azazel, and we suddenly get a shot from above: they are talking while standing within a sort of "magic" pentagram which is designed in tile on the sidewalk. But this image is not followed up, and we don’t know if it has any deeper significance. All of these good actors—Denzel Washington, John Goodman, Donald Sutherland—are lost in the vast wasteland of this script. What keeps this movie from being a BOMB is that the lead actors, even while on autopilot and with this turkey of a script, generate enough energy to produce a mild desire in the viewer to see what happens. Will Hobbes kill the demon; will it destroy him? (The professor of religion has said, enigmatically and characteristically enough, that the "right" person can destroy the demon. Does Hobbes have the "right stuff"?) The viewer, however, should be forewarned that meaning, theme, logic, and film aesthetics are at a premium here. To paraphrase Mark Twain in a slightly different context, those attempting to find a theme or moral in this film will be shot, or, perhaps, forced to sit through seven consecutive evenings of Waiting for Godot. |

|

| Go to Top of Page |

| Please send any comments or suggestions to: |

|

|