OLONY.

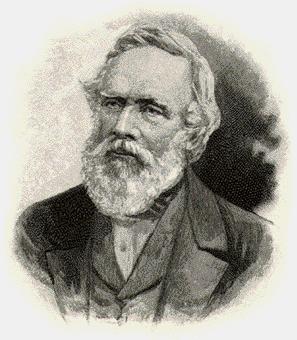

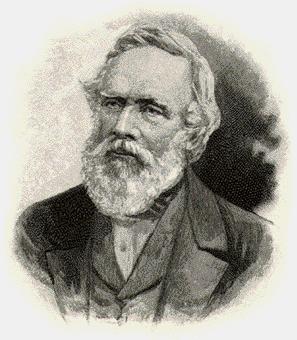

Two names are conspicuous above all others in the history of the early settlement. They

are those of Edward Gibbon Wakefield and George Fife Angas. To the former belongs the

honour of devising a new method for successful colonisation, and to the latter that of

being chiefly instrumental in bringing it to the test of actual experiment.

Mr. Wakefield was a political economist, and a reformer in the best sense of the term,

and Mr. Angas a colonist of exactly the right stamp. The one developed principles that

were sound as well as original, and the other laboured with sagacity and resoluteness to

give them practical effect. It would be difficult to say which of them rendered the

greatest service; they laboured in different departments, and there was no rivalry between

them.

The colonisation of South Australia was undertaken on altogether

novel principles. It was mooted in England at a period when emigration projects were

popular, for times were bad. The failure of some attempts, and notably that at Swan River

in Western Australia, led acute observers to see that the land-grant system was fatal to

prosperity, and among those who suggested better methods Mr. Wakefield took a foremost

place. The essential principle of his scheme was that land should be exchanged for labour

instead of being given away or alienated for a merely nominal sum. The idea of founding a

colony somewhere in southern Australia altogether independent of previous settlements

found powerful advocates, and after some years of agitation in public meetings and

otherwise ail Act was passed by the Imperial Parliament of 1834 in which it was embodied.

Under that Act commissioners were appointed and empowered to undertake the enterprise. It

was stipulated that no part of the expense incurred should fall upon the Home Government.

The commissioners were authorised to borrow fifty thousand pounds to defray the cost of

emigration, and a further sum of two hundred thousand pounds for the general charges of

founding the colony. By way of securing a sort of guarantee, they were restrained from

exercising their general powers until the sum of twenty thousand pounds had been invested

in exchequer bills in the names of trustees, and thirty-five thousand acres of land were

sold. It may be mentioned here that one clause in the Act expressly prohibited the

transportation of convicts to the colony, and that another provided for the appointment of

officers, chaplains, and clergymen, but this was omitted in the amending Act subsequently

passed. Thus the three fundamental principles on which the colony was founded were

self-support, anti-transportation, and the voluntary principle as applied to religion. In

the main, they have been steadily adhered to, any infringement of them being only

temporary, and always both stoutly and successfully resisted. Experience has demonstrated

their practical value, and they are, now adopted by all the Australian colonies, but at

that time they were untried, and therefore were subject to no little criticism and

opposition. All the more honour is due on that account to the earnest men who stood by

them through thick and thin, in evil report as well as good.

The colonisation of South Australia was undertaken on altogether

novel principles. It was mooted in England at a period when emigration projects were

popular, for times were bad. The failure of some attempts, and notably that at Swan River

in Western Australia, led acute observers to see that the land-grant system was fatal to

prosperity, and among those who suggested better methods Mr. Wakefield took a foremost

place. The essential principle of his scheme was that land should be exchanged for labour

instead of being given away or alienated for a merely nominal sum. The idea of founding a

colony somewhere in southern Australia altogether independent of previous settlements

found powerful advocates, and after some years of agitation in public meetings and

otherwise ail Act was passed by the Imperial Parliament of 1834 in which it was embodied.

Under that Act commissioners were appointed and empowered to undertake the enterprise. It

was stipulated that no part of the expense incurred should fall upon the Home Government.

The commissioners were authorised to borrow fifty thousand pounds to defray the cost of

emigration, and a further sum of two hundred thousand pounds for the general charges of

founding the colony. By way of securing a sort of guarantee, they were restrained from

exercising their general powers until the sum of twenty thousand pounds had been invested

in exchequer bills in the names of trustees, and thirty-five thousand acres of land were

sold. It may be mentioned here that one clause in the Act expressly prohibited the

transportation of convicts to the colony, and that another provided for the appointment of

officers, chaplains, and clergymen, but this was omitted in the amending Act subsequently

passed. Thus the three fundamental principles on which the colony was founded were

self-support, anti-transportation, and the voluntary principle as applied to religion. In

the main, they have been steadily adhered to, any infringement of them being only

temporary, and always both stoutly and successfully resisted. Experience has demonstrated

their practical value, and they are, now adopted by all the Australian colonies, but at

that time they were untried, and therefore were subject to no little criticism and

opposition. All the more honour is due on that account to the earnest men who stood by

them through thick and thin, in evil report as well as good.

Though the South Australian Association that had been formed to carry out the project

had succeeded thus far, the initial difficulties were not over, and indeed they proved so

great that the first board of commissioners resigned before any progress in actual

settlement was made. The chief obstacle was the necessity of selling sufficient land to

comply with the requirements of the statute. At this juncture, when the fate of the scheme

appeared to be hanging in the balance, Mr. Angas, who had all along been interested in it,

was induced to take a still more active and responsible part. Land orders had been issued

entitling each holder to an acre of town land and an eighty acre section in the country

for eighty-one pounds, but two months after the commencement of the sales not half the

number had been disposed of. Mr. Angas proposed that the price should be reduced to twelve

shillings per acre, and after some negotiations this suggestion was adopted in the

modified form that the preliminary sections should consist of one hundred and thirty-four

instead of eighty acres, with the provision that when the first governor arrived in the

colony the original arrangement should be reverted to. This being settled Mr. Angas

succeeded in forming the South Australian Company, of which he became chairman, and

resigned his seat on the board of commissioners, justly regarding the two positions as

incompatible.  The company took up a sufficient number of land orders

at the reduced rate to fulfil the stipulations of the Act, all other purchasers being

placed on the same more advantageous terms, and thus the enterprise was fairly launched.

Mr. Angas’ energy and fertility of resource had proved successful. From that time, he

took still greater interest in the scheme, emigrated to South Australia some years

afterwards, and to the time of his death was one of its most active, honoured, and

successful colonists. Early in 1836 the despatch of emigrants began, and on July 29th of

that year the "Duke of York," which was the first vessel to arrive, cast anchor

in Nepean Bay. A touch of romance accompanied the landing. The honour of being the first

person to set foot on shore had been coveted and discussed on board, and the captain had

chivalrously resolved to give it to the youngest member of the party —the infant

daughter of Mr. Beare, the second officer of the company. Accordingly " Baby Beare

" was carried through the surf by a stalwart sailor named Robert Russell, who placed

her feet on the wet sand amid the cheers of the passengers and crew.

The company took up a sufficient number of land orders

at the reduced rate to fulfil the stipulations of the Act, all other purchasers being

placed on the same more advantageous terms, and thus the enterprise was fairly launched.

Mr. Angas’ energy and fertility of resource had proved successful. From that time, he

took still greater interest in the scheme, emigrated to South Australia some years

afterwards, and to the time of his death was one of its most active, honoured, and

successful colonists. Early in 1836 the despatch of emigrants began, and on July 29th of

that year the "Duke of York," which was the first vessel to arrive, cast anchor

in Nepean Bay. A touch of romance accompanied the landing. The honour of being the first

person to set foot on shore had been coveted and discussed on board, and the captain had

chivalrously resolved to give it to the youngest member of the party —the infant

daughter of Mr. Beare, the second officer of the company. Accordingly " Baby Beare

" was carried through the surf by a stalwart sailor named Robert Russell, who placed

her feet on the wet sand amid the cheers of the passengers and crew.

Other vessels arrived in tolerably quick succession at the same rendezvous. Kangaroo

Island was at that time much better known, and more favorably reported upon than the

mainland. The general expectation was that the settlement would be made there, and steps

were taken accordingly by the company’s agents, so that Kingscote is chronologically

the premier town of South Australia. Its early abandonment resulted from the speedy

discovery of more suitable localities elsewhere.

When Colonel Light arrived in the month of August with a staff of surveyors, he entered

on a careful examination of the Country west of the Gulf of St. Vincent. Proceeding north

from Rapid Bay, he found the inlet discovered by Captain Jones to be the only secure

harbour on the coast, and was favourably impressed by his view of the plains at the foot

of Mount Lofty. A visit to Encounter Bay convinced him that the capabilities of that

region were inferior, and a similar result followed hi 3 inspection of Port Lincoln, for

though the harbour and scenery there were magnificent, the country was too poor for

profitable occupation. As the result of these observations, which experience has confirmed

in every respect, Holdfast Bay was selected for the place of final disembarkation, and

there, by December, 1836, most of the arrivals up to that time were congregated.

The governorship of the colony was offered in the first instance to Major-General Sir

C. Napier, who, however, stipulated that he was to be furnished with troops, and empowered

to draw on the Home Government in case of need. What visions of conquest he indulged in it

is hard to conjecture, but it is almost needless to say that his demands could not be

complied with. Thereupon, Captain Hindmarsh, R.N., a bluff, warm-hearted, typical British

seaman, was appointed. After calling at Port Lincoln, he arrived at Holdfast Bay on

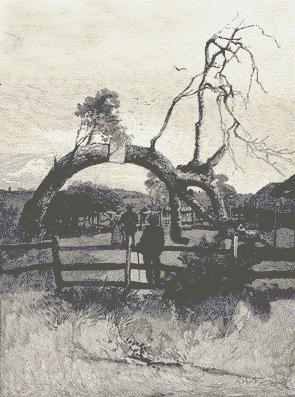

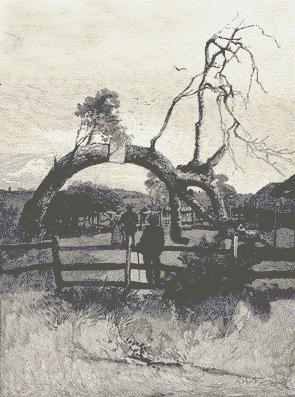

December 28th, 1836. At three o’clock that afternoon, under the shade of a gum-tree a

short distance from the beach, the proclamation was read, and the colony formally

inaugurated. The ceremony was rendered as imposing as the circumstances would admit.

Nearly all the settlers then on shore, numbering about two hundred, were present.  The

governor’s secretary read the proclamation, the Union jack was hoisted, and saluted

by the guns of the "Buffalo" which lay in the offing; two of those guns now

adorn the esplanade of Glenelg. A party of marines from the vessel fired a feu-de-joie,

and there were rounds upon rounds of cheers. A cold collation had been spread under the

trees, the usual patriotic toasts were duly honoured, the National Anthem, "Rule

Britannia," and other national songs were sung with true colonial fervour, and the

festivities were prolonged till a late hour of the night. Twenty-one years afterwards, the

majority of the colony was celebrated at the same place with unbounded enthusiasm, but

amid drenching torrents of rain. On that occasion, Governor MacDonnell affixed a tablet to

the historic tree recording the earlier event. The tree has now fallen into decay, but on

jubilee Day, December 28th, 1886, a small company assembled there, including some of the

pioneers, and planted other trees, so that after the original has perished some sylvan

memorial of the scene it witnessed might remain. Doubts have been cast on the authenticity

of the claims it is supposed to have, but if it did not actually overshadow Governor

Hindmarsh when the proclamation was made, it stood so near that the point is of little

consequence.

The

governor’s secretary read the proclamation, the Union jack was hoisted, and saluted

by the guns of the "Buffalo" which lay in the offing; two of those guns now

adorn the esplanade of Glenelg. A party of marines from the vessel fired a feu-de-joie,

and there were rounds upon rounds of cheers. A cold collation had been spread under the

trees, the usual patriotic toasts were duly honoured, the National Anthem, "Rule

Britannia," and other national songs were sung with true colonial fervour, and the

festivities were prolonged till a late hour of the night. Twenty-one years afterwards, the

majority of the colony was celebrated at the same place with unbounded enthusiasm, but

amid drenching torrents of rain. On that occasion, Governor MacDonnell affixed a tablet to

the historic tree recording the earlier event. The tree has now fallen into decay, but on

jubilee Day, December 28th, 1886, a small company assembled there, including some of the

pioneers, and planted other trees, so that after the original has perished some sylvan

memorial of the scene it witnessed might remain. Doubts have been cast on the authenticity

of the claims it is supposed to have, but if it did not actually overshadow Governor

Hindmarsh when the proclamation was made, it stood so near that the point is of little

consequence.

The final toast proposed by His Excellency at the al fresco lunch just referred

to was —"May the present unanimity continue as long as South Australia

exists." He moved about among the colonists exchanging pleasant greetings and by his

kindliness and affability won golden opinions on all sides. Unfortunately, the unanimity

vanished almost immediately, and with it good feeling and cordial co-operation. For a long

time afterwards in the history of the colony there were constant disagreements producing

irritation all round, and retarding progress in every way. At first the colonists were

comparatively idle —waiting to be put in possession of their lands, and idleness

wrought its proverbial results. Among the officials there was divided authority and

responsibility, which worked further mischief. The govern the resident commissioners, and

the surveyor-general had each large and independent powers, and in exercising them there

as mutual interference producing dissension and collision that was most injurious to the

prospects of the colony.

Considering all things, the course of events is not

very surprising, for it was an extremely trying situation. His Excellency entered the navy

at seven years of age and rose to the rank of rear-admiral. He had an extraordinary,

record, having been in nearly a hundred naval engagements including seven great actions,

amongst which were those of the "glorious first of June, the Nile, and Trafalgar. He

wore more distinctions at the close of his life than any other officer in the British Navy

save one. Such a career was not at all the best preparation for a position like that

occupied by Captain Hindmarsh. He felt hampered and thwarted. Though nominally supreme,

others had higher authority than he on matters about which he was most concerned. The

upshot was that when, at the end of fourteen months, he was recalled, Lord Glenelg, the

Secretary of State for the Colonies, wrote that on his own showing he appeared " to

be incapable of carrying on the government; with the exception of the judge and the

harbourmaster, he was, more or less, at variance with all the official functionaries of

the colony."

Considering all things, the course of events is not

very surprising, for it was an extremely trying situation. His Excellency entered the navy

at seven years of age and rose to the rank of rear-admiral. He had an extraordinary,

record, having been in nearly a hundred naval engagements including seven great actions,

amongst which were those of the "glorious first of June, the Nile, and Trafalgar. He

wore more distinctions at the close of his life than any other officer in the British Navy

save one. Such a career was not at all the best preparation for a position like that

occupied by Captain Hindmarsh. He felt hampered and thwarted. Though nominally supreme,

others had higher authority than he on matters about which he was most concerned. The

upshot was that when, at the end of fourteen months, he was recalled, Lord Glenelg, the

Secretary of State for the Colonies, wrote that on his own showing he appeared " to

be incapable of carrying on the government; with the exception of the judge and the

harbourmaster, he was, more or less, at variance with all the official functionaries of

the colony."

The chief subject of dispute was the site for the chief town of the settlement. Colonel

Light, as surveyor-general, was invested wit full power for its selection. He examined all

the places that ere suggested, and finally decided on the position which Adelaide

occupies. From this decision he never wavered, though he was sorely tried and tormented.

The governor, Sir J. Jeffcott —who was the first judge —and others, pressed for

the capital to be at Encounter Bay, having regard to the capabilities of the river Murray.

Port Lincoln had its advocates because of its splendid harbour. It was objected that the

chosen site was too far from the sea for a commercial centre, but to meet that difficulty

he consented to the survey of a secondary town called Port Adelaide, and the wisdom of

this arrangement is now fully justified. This, the principal port of the colony, was

surveyed at what was then called Port Misery on the inlet first seen by Captain Jones, and

afterwards explored by Mr. Pullen (subsequently Admiral Pullen), who always took great

interest in South Australia, and felt greatly aggrieved that his share in its early

settlement was so persistently ignored.

To Colonel Light’s clearness of judgment in the first instance, and to the

firmness and courage he displayed in standing by it against all opposition, the citizens

of Adelaide owe eternal gratitude. There can be no doubt that the harassing anxiety to

which he was subjected enfeebled his health and shortened his days. He died in 1839, and

to the last retained his confidence in the splendid future that lay before the city he had

planned. His great anxiety was to be known as its founder, and an inscription to that

effect was placed in his coffin. He was interred in the public square that bears his name,

and over his remains a handsome monument was erected from designs by Mr. Kingston, his

associate and successor, who was afterwards knighted, and who had also the honour of being

chosen Speaker of the first House of Assembly.

The worst immediate result of these disagreements was that great delay took

place in the work of surveying, so that months elapsed before any selection of land could

be made, and consequently nothing in the way of production was even attempted. For a

considerable time the settlers camped almost anywhere. The habitations they erected were

of the flimsiest materials. Government House was a reed hut, and most of the other

dwellings were of a similar order of architecture. Such edifices were of course peculiarly

liable to accidents, and when the old government hut was burned down in January, 1839,

nearly the whole of the executive and legislative records up to that date were consumed,

for by some fatuity they had been deposited within it. Life in those days was a sort of

long picnic. The genial climate of South Australia made bivouacking in the open air a

pleasant experience for the greater part of the year. Despite the squabbles of officials,

the settlers for the most part lived in harmony with each other. They made light of their

privations, and found a degree of pleasurable excitement in the shifts and contrivances to

which they had to resort. They introduced the amusements of civilised life without much

delay. Excursions up the "pretty little river" —as it was described at the

time —on which they had encamped, and into the hills were organised. An archery club

was started on August 15th 1837, and the first races were held on the following New

Year’s Day. Nor were the means, of supplying deeper needs neglected. The Rev. C. B.

Howard came out as colonial chaplain in the "Buffalo" with Governor Hindmarsh,

and by his tact, energy, and Christian charity won for himself an excellent reputation

that still endures. The Rev. T. Q. Stow, the first Congregational minister, was an early

arrival. He wrought in apostolic fashion, helping to build the first church of his

denomination with his own hands, and his name is perpetuated by one of the finest

ecclesiastical structures of the city. Wesleyan lay preachers were among the earliest

immigrants and they set to work with characteristic energy. Mr, White, now of Bathurst,

who preached the first sermon, had the uncommon experience of conducting another service

near the same locality more than fifty years afterwards. Members of the various sects

wrought with mutual helpfulness, and worshiped in a truly Christian concord.

The worst immediate result of these disagreements was that great delay took

place in the work of surveying, so that months elapsed before any selection of land could

be made, and consequently nothing in the way of production was even attempted. For a

considerable time the settlers camped almost anywhere. The habitations they erected were

of the flimsiest materials. Government House was a reed hut, and most of the other

dwellings were of a similar order of architecture. Such edifices were of course peculiarly

liable to accidents, and when the old government hut was burned down in January, 1839,

nearly the whole of the executive and legislative records up to that date were consumed,

for by some fatuity they had been deposited within it. Life in those days was a sort of

long picnic. The genial climate of South Australia made bivouacking in the open air a

pleasant experience for the greater part of the year. Despite the squabbles of officials,

the settlers for the most part lived in harmony with each other. They made light of their

privations, and found a degree of pleasurable excitement in the shifts and contrivances to

which they had to resort. They introduced the amusements of civilised life without much

delay. Excursions up the "pretty little river" —as it was described at the

time —on which they had encamped, and into the hills were organised. An archery club

was started on August 15th 1837, and the first races were held on the following New

Year’s Day. Nor were the means, of supplying deeper needs neglected. The Rev. C. B.

Howard came out as colonial chaplain in the "Buffalo" with Governor Hindmarsh,

and by his tact, energy, and Christian charity won for himself an excellent reputation

that still endures. The Rev. T. Q. Stow, the first Congregational minister, was an early

arrival. He wrought in apostolic fashion, helping to build the first church of his

denomination with his own hands, and his name is perpetuated by one of the finest

ecclesiastical structures of the city. Wesleyan lay preachers were among the earliest

immigrants and they set to work with characteristic energy. Mr, White, now of Bathurst,

who preached the first sermon, had the uncommon experience of conducting another service

near the same locality more than fifty years afterwards. Members of the various sects

wrought with mutual helpfulness, and worshiped in a truly Christian concord.

The colonists were, however, all the while drifting into difficulties. They busied

themselves to some extent in providing better shelter for their families, and at the

beginning of 1838 Adelaide contained fifty substantial and one hundred and fifty inferior

houses. At the same time, they were dependent on other lands for the necessaries of life.

There was neither cultivation nor trade worth speaking of. Food, of course, grew dearer.

Flour was worth thirty pounds per ton, beef one shilling per pound, tea four shillings per

pound, and at times these prices were greatly exceeded. Profiting by the opportunity, such

artisans as were there charged exorbitant prices. The "only watchmaker" got

seventeen shillings for cleaning a watch. The "Company" tried to carry on the

whale-fishery, and for some years the only exports were whalebone and oil, but there was

no external trace in either mineral, pastoral, or agricultural products.

After Captain Hindmarsh took his departure, the government was

administered for several months by the attorney-general, Mr. G. M. Stephen. A slight

improvement in the situation had already taken place, by what was called the overlanding

of stock from New South Wales, and as time passed on this method of turning the country to

account became more fully developed, and produced a beneficial change. The first drove

consisted of about, three hundred head of cattle that were brought by Mr. Joseph Hawdon

from the Goulburn. It was a bold enterprise, for nearly one thousand miles of unknown

country had to be traversed. The drovers were veritable explorers, for though they had

Mitchell’s tracks to guide them part of the way, and also Sturt’s report of the

Murray valley, so little was known of the interior that they found themselves confronted

by previously undiscovered rivers, and on the wrong side of some that were known. Their

route lay chiefly down the right bank of the Murray till within sight of Mount Barker,

which they left to the south, and then, after striking the Onkaparinga, misled by

incorrect maps, followed its course nearly to the sea. They reached Adelaide in April,

1838, having performed the journey in ten weeks, and lost scarcely a head of the cattle,

which arrived in splendid condition. No collision with natives had occurred, who indeed

had been found useful in pointing out short-cuts across the river-bends. Other parties

were less fortunate, but the practicability of the route had been proved, and by

succeeding ventures the country became stocked with cattle, sheep, and horses. Both

pastoral and agricultural operations were facilitated, and an impetus given to profitable

industry and trade. Mr. Stephen was efficient as an administrator. He bore his honours

meekly, but he became involved in litigation through some land transactions, and was not

sorry when Lieu tenant-Colonel Gawler, K.H., relieved him of his responsibility on October

12th, 1838.

After Captain Hindmarsh took his departure, the government was

administered for several months by the attorney-general, Mr. G. M. Stephen. A slight

improvement in the situation had already taken place, by what was called the overlanding

of stock from New South Wales, and as time passed on this method of turning the country to

account became more fully developed, and produced a beneficial change. The first drove

consisted of about, three hundred head of cattle that were brought by Mr. Joseph Hawdon

from the Goulburn. It was a bold enterprise, for nearly one thousand miles of unknown

country had to be traversed. The drovers were veritable explorers, for though they had

Mitchell’s tracks to guide them part of the way, and also Sturt’s report of the

Murray valley, so little was known of the interior that they found themselves confronted

by previously undiscovered rivers, and on the wrong side of some that were known. Their

route lay chiefly down the right bank of the Murray till within sight of Mount Barker,

which they left to the south, and then, after striking the Onkaparinga, misled by

incorrect maps, followed its course nearly to the sea. They reached Adelaide in April,

1838, having performed the journey in ten weeks, and lost scarcely a head of the cattle,

which arrived in splendid condition. No collision with natives had occurred, who indeed

had been found useful in pointing out short-cuts across the river-bends. Other parties

were less fortunate, but the practicability of the route had been proved, and by

succeeding ventures the country became stocked with cattle, sheep, and horses. Both

pastoral and agricultural operations were facilitated, and an impetus given to profitable

industry and trade. Mr. Stephen was efficient as an administrator. He bore his honours

meekly, but he became involved in litigation through some land transactions, and was not

sorry when Lieu tenant-Colonel Gawler, K.H., relieved him of his responsibility on October

12th, 1838.

From the moment of Governor Gawler’s arrival, he gave the impression that he

intended to go ahead. A cavalcade of horsemen went out to meet and welcome him on the road

between the landing-place and the city, but he shot past it at a hand-gallop on a blood

horse he had borrowed. This little incident illustrates in every minute particular his

entire career. He was firm in the saddle, he cared little for anybody, he travelled fast,

and he borrowed freely. To begin with, he was invested with greater authority than his

predecessor, for he held the offices of lieutenant-governor and resident commissioner, and

he soon showed that he meant to exercise his powers fully. A brief inspection revealed to

him the existing evils, and he set to work energetically to provide remedies. What civil

service there was had little order or organisation, for there were no suitable offices and

no regular office hours.  He announced

that all orders would have to be obeyed on pain of suspension or prompt dismissal, and

found his staff something more to do than quarrel. He reorganised the police force, and

called for volunteers to form a sort of militia, but was rather discomfited to find at the

first muster a company consisting of nine officers and six privates. There were about six

thousand people in the colony when he arrived, almost all of whom were hanging about the

city with very little to do. Perhaps emigration had been pushed on rather too rapidly, but

the delays Captain Hindmarsh had thrown in the way of surveying country sections had

operated disastrously. Unable to occupy the land, the owners of town allotments had taken

to jobbing and gambling in them for want of something better to fill up their time. The

governor checked this by pushing on the surveys, and insisting on the land-holders

entering on their property within a limited period. For the landless and unemployed, he

found work by commencing to build a substantial but not too pretentious Government House,

public offices, court-house, hospital, barracks, and gaol. He personally took part in the

work of exploration, and sent cut other parties so that intending settlers might know

where to find good land, and he took care that the available supply should always be in

advance of the demand.

He announced

that all orders would have to be obeyed on pain of suspension or prompt dismissal, and

found his staff something more to do than quarrel. He reorganised the police force, and

called for volunteers to form a sort of militia, but was rather discomfited to find at the

first muster a company consisting of nine officers and six privates. There were about six

thousand people in the colony when he arrived, almost all of whom were hanging about the

city with very little to do. Perhaps emigration had been pushed on rather too rapidly, but

the delays Captain Hindmarsh had thrown in the way of surveying country sections had

operated disastrously. Unable to occupy the land, the owners of town allotments had taken

to jobbing and gambling in them for want of something better to fill up their time. The

governor checked this by pushing on the surveys, and insisting on the land-holders

entering on their property within a limited period. For the landless and unemployed, he

found work by commencing to build a substantial but not too pretentious Government House,

public offices, court-house, hospital, barracks, and gaol. He personally took part in the

work of exploration, and sent cut other parties so that intending settlers might know

where to find good land, and he took care that the available supply should always be in

advance of the demand.

This policy had the immediate effect of diminishing the quarrels between public

officials, while the energies of the people were directed into profitable channels, for

they were almost forced to stock and cultivate the land through being, practically driven

out into the country; order, activity, and energy were infused into every department, and

the foundations of future prosperity substantially laid. As a direct consequence, business

flourished, confidence in the stability of the colony was increased, and progress made in

social, educational, philanthropic, and religious movements. Among other tokens of the

enterprising spirit that was abroad were the expansion of settlement, and the schemes

adopted for penetrating the interior to the north and west. Pioneers established

themselves in the Mount Lofty ranges as far east as Hahndorf and Mount Barker. An

"Adelaide Association" was formed to take up land at Port Lincoln, but for

reasons that are now perfectly intelligible met with but little success. Captain Sturt was

in Adelaide, sanguine as to future probabilities, and Mr. E. J. Eyre was sent out on his

memorable expeditions. The net results of Governor Gawler’s term of office, which was

less than three years in duration, may be briefly summarised. The population was more than

doubled; the land under cultivation increased from eighty-six acres to two thousand five

hundred and three; the sheep depastured from twenty-eight thousand to more than two

hundred thousand; and the export trade from almost nil to over one hundred thousand pounds

in annual value. It is evident that the way to prosperity had been discovered and entered

upon. Had the authorities in England judiciously sustained their representative, it would

have led to success, but again the evil genius of divided councils intervened, bringing

Colonel Gawler’s term to an abrupt and inglorious termination and involving the

infant colony in severe though temporary disaster.

In order to carry out the programme he had begun, Colonel Gawler drew on the

‘South Australian Commissioners to the extent of one hundred and fifty-five thousand

pounds, and this sum, added to the other items of indebtedness, made a total of two

hundred and sixty-nine thousand pounds.  The

commissioners grew alarmed, and it is believed were influenced by exaggerated reports of

the extravagant rate at which their executive officer was carrying on. Communications were

slow, and hence explanations necessarily difficult. They seem to have thought delay was

dangerous, and accordingly resolved on the extreme step of dishonouring the bills and

recalling the governor. History has largely exonerated him, and shown that his superiors

were somewhat unreasonable. They sent shipload after shipload of emigrants, for whom their

representative had to provide in some way, and they ought to have supplied him with the

necessary funds. He felt that he had no option, and believed he was acting within his

powers. His faith in the ability of the province to meet its liabilities was well

grounded, and had he been allowed to work out his plans to their final issue there would

probably have been no trouble. The unexpected intelligence from England came like a

thunderclap on the entire colony, and precipitated an acute crisis. It not only shook and

well-nigh destroyed confidence within, but provoked adverse criticisms from without on its

fundamental principles, which for a time were unhesitatingly pronounced to be a proved

failure.

The

commissioners grew alarmed, and it is believed were influenced by exaggerated reports of

the extravagant rate at which their executive officer was carrying on. Communications were

slow, and hence explanations necessarily difficult. They seem to have thought delay was

dangerous, and accordingly resolved on the extreme step of dishonouring the bills and

recalling the governor. History has largely exonerated him, and shown that his superiors

were somewhat unreasonable. They sent shipload after shipload of emigrants, for whom their

representative had to provide in some way, and they ought to have supplied him with the

necessary funds. He felt that he had no option, and believed he was acting within his

powers. His faith in the ability of the province to meet its liabilities was well

grounded, and had he been allowed to work out his plans to their final issue there would

probably have been no trouble. The unexpected intelligence from England came like a

thunderclap on the entire colony, and precipitated an acute crisis. It not only shook and

well-nigh destroyed confidence within, but provoked adverse criticisms from without on its

fundamental principles, which for a time were unhesitatingly pronounced to be a proved

failure.

The manner in which Colonel Gawler was treated was an aggravation of the treatment

itself. Some months previously a toil-worn and solitary stranger had arrived in Adelaide

from Western Australia, where he had been engaged in exploration. He had been wounded by

native spears, and was weary from excessive toll. While waiting for a vessel to take him

to England, he was hospitably entertained at Government House, and informed of every

particular in which a stranger and one connected with colonial affairs would be likely to

take an interest. When he left he was bidden "God-speed" on his voyage; but on

his return, without any previous intimation, he again proceeded to Government House, made

his bow, informed the governor that some of his drafts had been repudiated, produced from

his own pocket and handed him his recall, and showed him his own appointment as the future

governor. Thus unceremoniously did Captain George Grey turn out Colonel George Gawler.

There was of course tremendous excitement and wide-spread ruin. By discrediting the

colony, everything it contained was depreciated, and the result was universal panic and a

commercial crash.

Amid all this, the colonists stood by their late

governor, and testified to their appreciation of his services by complimentary farewell

addresses and a presentation of five hundred pounds, which he invested in land so as to

maintain a connecting link with the colony and show his confidence in its future. It was

an unfortunate riding to a promising career. As a soldier, he had seen active service at

Badajoz, Vitoria, Toulouse, and Waterloo, besides many minor engagements. The Duke of

Wellington —no mean judge of character —once said of him, "Gawler could not

act otherwise than wisely, for he never did a foolish thing in his life." The policy

which relegated him to obscurity plunged the colony into difficulties from which it did

not recover for years. Its upshot was that the management of the commissioners came to an

end. The public debt, including fifty-nine thousand pounds, which sum Captain Grey was

authorised to draw, was provided for by a loan that was repaid by instalments. Thus the

experimental stage of colonisation may be said to have terminated; and in stormy weather,

after a gleam of sunshine, the work of founding the colony was completed.

Amid all this, the colonists stood by their late

governor, and testified to their appreciation of his services by complimentary farewell

addresses and a presentation of five hundred pounds, which he invested in land so as to

maintain a connecting link with the colony and show his confidence in its future. It was

an unfortunate riding to a promising career. As a soldier, he had seen active service at

Badajoz, Vitoria, Toulouse, and Waterloo, besides many minor engagements. The Duke of

Wellington —no mean judge of character —once said of him, "Gawler could not

act otherwise than wisely, for he never did a foolish thing in his life." The policy

which relegated him to obscurity plunged the colony into difficulties from which it did

not recover for years. Its upshot was that the management of the commissioners came to an

end. The public debt, including fifty-nine thousand pounds, which sum Captain Grey was

authorised to draw, was provided for by a loan that was repaid by instalments. Thus the

experimental stage of colonisation may be said to have terminated; and in stormy weather,

after a gleam of sunshine, the work of founding the colony was completed.

cont...

click here to return to main page

The colonisation of South Australia was undertaken on altogether

novel principles. It was mooted in England at a period when emigration projects were

popular, for times were bad. The failure of some attempts, and notably that at Swan River

in Western Australia, led acute observers to see that the land-grant system was fatal to

prosperity, and among those who suggested better methods Mr. Wakefield took a foremost

place. The essential principle of his scheme was that land should be exchanged for labour

instead of being given away or alienated for a merely nominal sum. The idea of founding a

colony somewhere in southern Australia altogether independent of previous settlements

found powerful advocates, and after some years of agitation in public meetings and

otherwise ail Act was passed by the Imperial Parliament of 1834 in which it was embodied.

Under that Act commissioners were appointed and empowered to undertake the enterprise. It

was stipulated that no part of the expense incurred should fall upon the Home Government.

The commissioners were authorised to borrow fifty thousand pounds to defray the cost of

emigration, and a further sum of two hundred thousand pounds for the general charges of

founding the colony. By way of securing a sort of guarantee, they were restrained from

exercising their general powers until the sum of twenty thousand pounds had been invested

in exchequer bills in the names of trustees, and thirty-five thousand acres of land were

sold. It may be mentioned here that one clause in the Act expressly prohibited the

transportation of convicts to the colony, and that another provided for the appointment of

officers, chaplains, and clergymen, but this was omitted in the amending Act subsequently

passed. Thus the three fundamental principles on which the colony was founded were

self-support, anti-transportation, and the voluntary principle as applied to religion. In

the main, they have been steadily adhered to, any infringement of them being only

temporary, and always both stoutly and successfully resisted. Experience has demonstrated

their practical value, and they are, now adopted by all the Australian colonies, but at

that time they were untried, and therefore were subject to no little criticism and

opposition. All the more honour is due on that account to the earnest men who stood by

them through thick and thin, in evil report as well as good.

The colonisation of South Australia was undertaken on altogether

novel principles. It was mooted in England at a period when emigration projects were

popular, for times were bad. The failure of some attempts, and notably that at Swan River

in Western Australia, led acute observers to see that the land-grant system was fatal to

prosperity, and among those who suggested better methods Mr. Wakefield took a foremost

place. The essential principle of his scheme was that land should be exchanged for labour

instead of being given away or alienated for a merely nominal sum. The idea of founding a

colony somewhere in southern Australia altogether independent of previous settlements

found powerful advocates, and after some years of agitation in public meetings and

otherwise ail Act was passed by the Imperial Parliament of 1834 in which it was embodied.

Under that Act commissioners were appointed and empowered to undertake the enterprise. It

was stipulated that no part of the expense incurred should fall upon the Home Government.

The commissioners were authorised to borrow fifty thousand pounds to defray the cost of

emigration, and a further sum of two hundred thousand pounds for the general charges of

founding the colony. By way of securing a sort of guarantee, they were restrained from

exercising their general powers until the sum of twenty thousand pounds had been invested

in exchequer bills in the names of trustees, and thirty-five thousand acres of land were

sold. It may be mentioned here that one clause in the Act expressly prohibited the

transportation of convicts to the colony, and that another provided for the appointment of

officers, chaplains, and clergymen, but this was omitted in the amending Act subsequently

passed. Thus the three fundamental principles on which the colony was founded were

self-support, anti-transportation, and the voluntary principle as applied to religion. In

the main, they have been steadily adhered to, any infringement of them being only

temporary, and always both stoutly and successfully resisted. Experience has demonstrated

their practical value, and they are, now adopted by all the Australian colonies, but at

that time they were untried, and therefore were subject to no little criticism and

opposition. All the more honour is due on that account to the earnest men who stood by

them through thick and thin, in evil report as well as good. The company took up a sufficient number of land orders

at the reduced rate to fulfil the stipulations of the Act, all other purchasers being

placed on the same more advantageous terms, and thus the enterprise was fairly launched.

Mr. Angas’ energy and fertility of resource had proved successful. From that time, he

took still greater interest in the scheme, emigrated to South Australia some years

afterwards, and to the time of his death was one of its most active, honoured, and

successful colonists. Early in 1836 the despatch of emigrants began, and on July 29th of

that year the "Duke of York," which was the first vessel to arrive, cast anchor

in Nepean Bay. A touch of romance accompanied the landing. The honour of being the first

person to set foot on shore had been coveted and discussed on board, and the captain had

chivalrously resolved to give it to the youngest member of the party —the infant

daughter of Mr. Beare, the second officer of the company. Accordingly " Baby Beare

" was carried through the surf by a stalwart sailor named Robert Russell, who placed

her feet on the wet sand amid the cheers of the passengers and crew.

The company took up a sufficient number of land orders

at the reduced rate to fulfil the stipulations of the Act, all other purchasers being

placed on the same more advantageous terms, and thus the enterprise was fairly launched.

Mr. Angas’ energy and fertility of resource had proved successful. From that time, he

took still greater interest in the scheme, emigrated to South Australia some years

afterwards, and to the time of his death was one of its most active, honoured, and

successful colonists. Early in 1836 the despatch of emigrants began, and on July 29th of

that year the "Duke of York," which was the first vessel to arrive, cast anchor

in Nepean Bay. A touch of romance accompanied the landing. The honour of being the first

person to set foot on shore had been coveted and discussed on board, and the captain had

chivalrously resolved to give it to the youngest member of the party —the infant

daughter of Mr. Beare, the second officer of the company. Accordingly " Baby Beare

" was carried through the surf by a stalwart sailor named Robert Russell, who placed

her feet on the wet sand amid the cheers of the passengers and crew. The

governor’s secretary read the proclamation, the Union jack was hoisted, and saluted

by the guns of the "Buffalo" which lay in the offing; two of those guns now

adorn the esplanade of Glenelg. A party of marines from the vessel fired a feu-de-joie,

and there were rounds upon rounds of cheers. A cold collation had been spread under the

trees, the usual patriotic toasts were duly honoured, the National Anthem, "Rule

Britannia," and other national songs were sung with true colonial fervour, and the

festivities were prolonged till a late hour of the night. Twenty-one years afterwards, the

majority of the colony was celebrated at the same place with unbounded enthusiasm, but

amid drenching torrents of rain. On that occasion, Governor MacDonnell affixed a tablet to

the historic tree recording the earlier event. The tree has now fallen into decay, but on

jubilee Day, December 28th, 1886, a small company assembled there, including some of the

pioneers, and planted other trees, so that after the original has perished some sylvan

memorial of the scene it witnessed might remain. Doubts have been cast on the authenticity

of the claims it is supposed to have, but if it did not actually overshadow Governor

Hindmarsh when the proclamation was made, it stood so near that the point is of little

consequence.

The

governor’s secretary read the proclamation, the Union jack was hoisted, and saluted

by the guns of the "Buffalo" which lay in the offing; two of those guns now

adorn the esplanade of Glenelg. A party of marines from the vessel fired a feu-de-joie,

and there were rounds upon rounds of cheers. A cold collation had been spread under the

trees, the usual patriotic toasts were duly honoured, the National Anthem, "Rule

Britannia," and other national songs were sung with true colonial fervour, and the

festivities were prolonged till a late hour of the night. Twenty-one years afterwards, the

majority of the colony was celebrated at the same place with unbounded enthusiasm, but

amid drenching torrents of rain. On that occasion, Governor MacDonnell affixed a tablet to

the historic tree recording the earlier event. The tree has now fallen into decay, but on

jubilee Day, December 28th, 1886, a small company assembled there, including some of the

pioneers, and planted other trees, so that after the original has perished some sylvan

memorial of the scene it witnessed might remain. Doubts have been cast on the authenticity

of the claims it is supposed to have, but if it did not actually overshadow Governor

Hindmarsh when the proclamation was made, it stood so near that the point is of little

consequence. Considering all things, the course of events is not

very surprising, for it was an extremely trying situation. His Excellency entered the navy

at seven years of age and rose to the rank of rear-admiral. He had an extraordinary,

record, having been in nearly a hundred naval engagements including seven great actions,

amongst which were those of the "glorious first of June, the Nile, and Trafalgar. He

wore more distinctions at the close of his life than any other officer in the British Navy

save one. Such a career was not at all the best preparation for a position like that

occupied by Captain Hindmarsh. He felt hampered and thwarted. Though nominally supreme,

others had higher authority than he on matters about which he was most concerned. The

upshot was that when, at the end of fourteen months, he was recalled, Lord Glenelg, the

Secretary of State for the Colonies, wrote that on his own showing he appeared " to

be incapable of carrying on the government; with the exception of the judge and the

harbourmaster, he was, more or less, at variance with all the official functionaries of

the colony."

Considering all things, the course of events is not

very surprising, for it was an extremely trying situation. His Excellency entered the navy

at seven years of age and rose to the rank of rear-admiral. He had an extraordinary,

record, having been in nearly a hundred naval engagements including seven great actions,

amongst which were those of the "glorious first of June, the Nile, and Trafalgar. He

wore more distinctions at the close of his life than any other officer in the British Navy

save one. Such a career was not at all the best preparation for a position like that

occupied by Captain Hindmarsh. He felt hampered and thwarted. Though nominally supreme,

others had higher authority than he on matters about which he was most concerned. The

upshot was that when, at the end of fourteen months, he was recalled, Lord Glenelg, the

Secretary of State for the Colonies, wrote that on his own showing he appeared " to

be incapable of carrying on the government; with the exception of the judge and the

harbourmaster, he was, more or less, at variance with all the official functionaries of

the colony." The worst immediate result of these disagreements was that great delay took

place in the work of surveying, so that months elapsed before any selection of land could

be made, and consequently nothing in the way of production was even attempted. For a

considerable time the settlers camped almost anywhere. The habitations they erected were

of the flimsiest materials. Government House was a reed hut, and most of the other

dwellings were of a similar order of architecture. Such edifices were of course peculiarly

liable to accidents, and when the old government hut was burned down in January, 1839,

nearly the whole of the executive and legislative records up to that date were consumed,

for by some fatuity they had been deposited within it. Life in those days was a sort of

long picnic. The genial climate of South Australia made bivouacking in the open air a

pleasant experience for the greater part of the year. Despite the squabbles of officials,

the settlers for the most part lived in harmony with each other. They made light of their

privations, and found a degree of pleasurable excitement in the shifts and contrivances to

which they had to resort. They introduced the amusements of civilised life without much

delay. Excursions up the "pretty little river" —as it was described at the

time —on which they had encamped, and into the hills were organised. An archery club

was started on August 15th 1837, and the first races were held on the following New

Year’s Day. Nor were the means, of supplying deeper needs neglected. The Rev. C. B.

Howard came out as colonial chaplain in the "Buffalo" with Governor Hindmarsh,

and by his tact, energy, and Christian charity won for himself an excellent reputation

that still endures. The Rev. T. Q. Stow, the first Congregational minister, was an early

arrival. He wrought in apostolic fashion, helping to build the first church of his

denomination with his own hands, and his name is perpetuated by one of the finest

ecclesiastical structures of the city. Wesleyan lay preachers were among the earliest

immigrants and they set to work with characteristic energy. Mr, White, now of Bathurst,

who preached the first sermon, had the uncommon experience of conducting another service

near the same locality more than fifty years afterwards. Members of the various sects

wrought with mutual helpfulness, and worshiped in a truly Christian concord.

The worst immediate result of these disagreements was that great delay took

place in the work of surveying, so that months elapsed before any selection of land could

be made, and consequently nothing in the way of production was even attempted. For a

considerable time the settlers camped almost anywhere. The habitations they erected were

of the flimsiest materials. Government House was a reed hut, and most of the other

dwellings were of a similar order of architecture. Such edifices were of course peculiarly

liable to accidents, and when the old government hut was burned down in January, 1839,

nearly the whole of the executive and legislative records up to that date were consumed,

for by some fatuity they had been deposited within it. Life in those days was a sort of

long picnic. The genial climate of South Australia made bivouacking in the open air a

pleasant experience for the greater part of the year. Despite the squabbles of officials,

the settlers for the most part lived in harmony with each other. They made light of their

privations, and found a degree of pleasurable excitement in the shifts and contrivances to

which they had to resort. They introduced the amusements of civilised life without much

delay. Excursions up the "pretty little river" —as it was described at the

time —on which they had encamped, and into the hills were organised. An archery club

was started on August 15th 1837, and the first races were held on the following New

Year’s Day. Nor were the means, of supplying deeper needs neglected. The Rev. C. B.

Howard came out as colonial chaplain in the "Buffalo" with Governor Hindmarsh,

and by his tact, energy, and Christian charity won for himself an excellent reputation

that still endures. The Rev. T. Q. Stow, the first Congregational minister, was an early

arrival. He wrought in apostolic fashion, helping to build the first church of his

denomination with his own hands, and his name is perpetuated by one of the finest

ecclesiastical structures of the city. Wesleyan lay preachers were among the earliest

immigrants and they set to work with characteristic energy. Mr, White, now of Bathurst,

who preached the first sermon, had the uncommon experience of conducting another service

near the same locality more than fifty years afterwards. Members of the various sects

wrought with mutual helpfulness, and worshiped in a truly Christian concord. After Captain Hindmarsh took his departure, the government was

administered for several months by the attorney-general, Mr. G. M. Stephen. A slight

improvement in the situation had already taken place, by what was called the overlanding

of stock from New South Wales, and as time passed on this method of turning the country to

account became more fully developed, and produced a beneficial change. The first drove

consisted of about, three hundred head of cattle that were brought by Mr. Joseph Hawdon

from the Goulburn. It was a bold enterprise, for nearly one thousand miles of unknown

country had to be traversed. The drovers were veritable explorers, for though they had

Mitchell’s tracks to guide them part of the way, and also Sturt’s report of the

Murray valley, so little was known of the interior that they found themselves confronted

by previously undiscovered rivers, and on the wrong side of some that were known. Their

route lay chiefly down the right bank of the Murray till within sight of Mount Barker,

which they left to the south, and then, after striking the Onkaparinga, misled by

incorrect maps, followed its course nearly to the sea. They reached Adelaide in April,

1838, having performed the journey in ten weeks, and lost scarcely a head of the cattle,

which arrived in splendid condition. No collision with natives had occurred, who indeed

had been found useful in pointing out short-cuts across the river-bends. Other parties

were less fortunate, but the practicability of the route had been proved, and by

succeeding ventures the country became stocked with cattle, sheep, and horses. Both

pastoral and agricultural operations were facilitated, and an impetus given to profitable

industry and trade. Mr. Stephen was efficient as an administrator. He bore his honours

meekly, but he became involved in litigation through some land transactions, and was not

sorry when Lieu tenant-Colonel Gawler, K.H., relieved him of his responsibility on October

12th, 1838.

After Captain Hindmarsh took his departure, the government was

administered for several months by the attorney-general, Mr. G. M. Stephen. A slight

improvement in the situation had already taken place, by what was called the overlanding

of stock from New South Wales, and as time passed on this method of turning the country to

account became more fully developed, and produced a beneficial change. The first drove

consisted of about, three hundred head of cattle that were brought by Mr. Joseph Hawdon

from the Goulburn. It was a bold enterprise, for nearly one thousand miles of unknown

country had to be traversed. The drovers were veritable explorers, for though they had

Mitchell’s tracks to guide them part of the way, and also Sturt’s report of the

Murray valley, so little was known of the interior that they found themselves confronted

by previously undiscovered rivers, and on the wrong side of some that were known. Their

route lay chiefly down the right bank of the Murray till within sight of Mount Barker,

which they left to the south, and then, after striking the Onkaparinga, misled by

incorrect maps, followed its course nearly to the sea. They reached Adelaide in April,

1838, having performed the journey in ten weeks, and lost scarcely a head of the cattle,

which arrived in splendid condition. No collision with natives had occurred, who indeed

had been found useful in pointing out short-cuts across the river-bends. Other parties

were less fortunate, but the practicability of the route had been proved, and by

succeeding ventures the country became stocked with cattle, sheep, and horses. Both

pastoral and agricultural operations were facilitated, and an impetus given to profitable

industry and trade. Mr. Stephen was efficient as an administrator. He bore his honours

meekly, but he became involved in litigation through some land transactions, and was not

sorry when Lieu tenant-Colonel Gawler, K.H., relieved him of his responsibility on October

12th, 1838. He announced

that all orders would have to be obeyed on pain of suspension or prompt dismissal, and

found his staff something more to do than quarrel. He reorganised the police force, and

called for volunteers to form a sort of militia, but was rather discomfited to find at the

first muster a company consisting of nine officers and six privates. There were about six

thousand people in the colony when he arrived, almost all of whom were hanging about the

city with very little to do. Perhaps emigration had been pushed on rather too rapidly, but

the delays Captain Hindmarsh had thrown in the way of surveying country sections had

operated disastrously. Unable to occupy the land, the owners of town allotments had taken

to jobbing and gambling in them for want of something better to fill up their time. The

governor checked this by pushing on the surveys, and insisting on the land-holders

entering on their property within a limited period. For the landless and unemployed, he

found work by commencing to build a substantial but not too pretentious Government House,

public offices, court-house, hospital, barracks, and gaol. He personally took part in the

work of exploration, and sent cut other parties so that intending settlers might know

where to find good land, and he took care that the available supply should always be in

advance of the demand.

He announced

that all orders would have to be obeyed on pain of suspension or prompt dismissal, and

found his staff something more to do than quarrel. He reorganised the police force, and

called for volunteers to form a sort of militia, but was rather discomfited to find at the

first muster a company consisting of nine officers and six privates. There were about six

thousand people in the colony when he arrived, almost all of whom were hanging about the

city with very little to do. Perhaps emigration had been pushed on rather too rapidly, but

the delays Captain Hindmarsh had thrown in the way of surveying country sections had

operated disastrously. Unable to occupy the land, the owners of town allotments had taken

to jobbing and gambling in them for want of something better to fill up their time. The

governor checked this by pushing on the surveys, and insisting on the land-holders

entering on their property within a limited period. For the landless and unemployed, he

found work by commencing to build a substantial but not too pretentious Government House,

public offices, court-house, hospital, barracks, and gaol. He personally took part in the

work of exploration, and sent cut other parties so that intending settlers might know

where to find good land, and he took care that the available supply should always be in

advance of the demand. The

commissioners grew alarmed, and it is believed were influenced by exaggerated reports of

the extravagant rate at which their executive officer was carrying on. Communications were

slow, and hence explanations necessarily difficult. They seem to have thought delay was

dangerous, and accordingly resolved on the extreme step of dishonouring the bills and

recalling the governor. History has largely exonerated him, and shown that his superiors

were somewhat unreasonable. They sent shipload after shipload of emigrants, for whom their

representative had to provide in some way, and they ought to have supplied him with the

necessary funds. He felt that he had no option, and believed he was acting within his

powers. His faith in the ability of the province to meet its liabilities was well

grounded, and had he been allowed to work out his plans to their final issue there would

probably have been no trouble. The unexpected intelligence from England came like a

thunderclap on the entire colony, and precipitated an acute crisis. It not only shook and

well-nigh destroyed confidence within, but provoked adverse criticisms from without on its

fundamental principles, which for a time were unhesitatingly pronounced to be a proved

failure.

The

commissioners grew alarmed, and it is believed were influenced by exaggerated reports of

the extravagant rate at which their executive officer was carrying on. Communications were

slow, and hence explanations necessarily difficult. They seem to have thought delay was

dangerous, and accordingly resolved on the extreme step of dishonouring the bills and

recalling the governor. History has largely exonerated him, and shown that his superiors

were somewhat unreasonable. They sent shipload after shipload of emigrants, for whom their

representative had to provide in some way, and they ought to have supplied him with the

necessary funds. He felt that he had no option, and believed he was acting within his

powers. His faith in the ability of the province to meet its liabilities was well

grounded, and had he been allowed to work out his plans to their final issue there would

probably have been no trouble. The unexpected intelligence from England came like a

thunderclap on the entire colony, and precipitated an acute crisis. It not only shook and

well-nigh destroyed confidence within, but provoked adverse criticisms from without on its

fundamental principles, which for a time were unhesitatingly pronounced to be a proved

failure. Amid all this, the colonists stood by their late

governor, and testified to their appreciation of his services by complimentary farewell

addresses and a presentation of five hundred pounds, which he invested in land so as to

maintain a connecting link with the colony and show his confidence in its future. It was

an unfortunate riding to a promising career. As a soldier, he had seen active service at

Badajoz, Vitoria, Toulouse, and Waterloo, besides many minor engagements. The Duke of

Wellington —no mean judge of character —once said of him, "Gawler could not

act otherwise than wisely, for he never did a foolish thing in his life." The policy

which relegated him to obscurity plunged the colony into difficulties from which it did

not recover for years. Its upshot was that the management of the commissioners came to an

end. The public debt, including fifty-nine thousand pounds, which sum Captain Grey was

authorised to draw, was provided for by a loan that was repaid by instalments. Thus the

experimental stage of colonisation may be said to have terminated; and in stormy weather,

after a gleam of sunshine, the work of founding the colony was completed.

Amid all this, the colonists stood by their late

governor, and testified to their appreciation of his services by complimentary farewell

addresses and a presentation of five hundred pounds, which he invested in land so as to

maintain a connecting link with the colony and show his confidence in its future. It was

an unfortunate riding to a promising career. As a soldier, he had seen active service at

Badajoz, Vitoria, Toulouse, and Waterloo, besides many minor engagements. The Duke of

Wellington —no mean judge of character —once said of him, "Gawler could not

act otherwise than wisely, for he never did a foolish thing in his life." The policy

which relegated him to obscurity plunged the colony into difficulties from which it did

not recover for years. Its upshot was that the management of the commissioners came to an

end. The public debt, including fifty-nine thousand pounds, which sum Captain Grey was

authorised to draw, was provided for by a loan that was repaid by instalments. Thus the

experimental stage of colonisation may be said to have terminated; and in stormy weather,

after a gleam of sunshine, the work of founding the colony was completed.