SOUTH AUSTRALIA - TOPOGRAPHICAL DESCIPTION 2 ...

Atlas Page 84

By Henry T. Burgess

ADELAIDE.

PASSING through Backstairs Passage at early dawn, with the light-house on the low rocky promontory of Cape Jervis close to the right hand, that on Cape Willoughby twinkling astern, and the scrub-covered heights of Kangaroo Island dimly discernible through the haze on the left, visitors to the colony have commonly a most enjoyable run up the Gulf. Following a succession of rugged cliffs and picturesque bays, the valley in which Yankalilla lies is opened. As the sun rises above the dark inland ranges, Willunga is seen on the slope beyond Mount Terrible, overlooking the plains beyond Aldinga. Bold cliffs succeed the gleaming sand-hills at the mouth of the Onkaparinga, and as the anchorage at Holdfast Bay is neared several miles of slightly curving shore become visible. Behind the shining beach are low sand-hills, with here and there a handsome villa looking down upon the sea. About the middle of the arc a noble esplanade seems to rise from the water’s edge, with towers and clustering’ roofs beyond it. From a pier crowned with a lighthouse a steam launch comes puffing out for the malls, in which passengers who may wish it can go ashore. The white sails of yachts and fishing-boats are glancing to and fro. In the distance is the striking Mount Lofty range, receding from the shore, and on its highest point a white beacon-tower erected for a landmark catches the sun. Among the hills, and partly showing through the trees that adorn their slopes, the mansions of wealthy colonists are discernible. Several miles away to the left, and apparently in the centre of the plain, the Post Office tower shows the site of the metropolis, and still farther north a cloud of smoke hangs over the Port. With a smooth sea the going ashore is easy. Smart little steamers ply to the landing stages on the pier; groups of gaily-dressed promenaders are waiting there to welcome the arrivals; and at the inshore end of it the Adelaide train stands in the middle of the principal street.

Sometimes, however, the scene is very different from this. When a strong southwest wind brings up a heavy sea from "outside," and clouds hang low on the hills, and sheets of driving rain obscure the landscape, larding at Glenelg is anything but a pleasant experience. The ocean-steamer rolls more than a little, and by its side the cockle-shell, as it seems, which affords the only communication with the shore, dances uneasily on the billows, straining at the hawsers fore and aft. It is a work requiring no small dexterity to sling the mailbags aboard, and a more difficult feat still for a nervous passenger to seize the right moment for descent. The P. and O. steamers make Glenelg their port of call, but the Orient liners, the Messageries Maritimes, and some others, go on to the quieter waters of Largs Bay, round Point Malcolm. Here, and at the Semaphore, the Grange, and Henley Beach, there are substantial jetties and rail communication with the city. Intercolonial steamers pass by the outer anchorages, and rounding the light-house, enter the Port river between Torrens Island, on which is the quarantine station, and Lefevre’s Peninsula, finding in the Port basin as sheltered a harbour as could be desired. From either point of disembarkation, there is a run of only, a few miles over level plains to the city, and on arrival there the discomforts of getting ashore are speedily forgotten.

Adelaide is beautiful for situation, and beautiful in itself. The municipality is divided into two portions by a belt of parklands through which runs the Torrens. The southern and larger part is the real metropolis, and North Adelaide is one of its far-stretching suburbs. It is laid out on a plateau about one hundred and seventy feet above the sea, almost an exact parallelogram, covering a square mile, the alignment of three of its terraces being in accordance with the cardinal points of the compass, and that of the fourth only broken to adapt it to the configuration of the ground. It is traversed by broad and well-paved streets, and at the intersection of the widest of them are open squares, five in number, handsomely fenced, planted with trees, and musical in some cases with the splash of fountains —shady retreats for loungers, and breathing spaces for the city population. All round it lie the parklands, a series of pleasure-grounds such as few cities of its size can boast. The Torrens in the course of years has worn for itself a wide channel, across which a substantial dam of masonry has been constructed, thereby forming a winding lake nearly two miles in length. It is spanned by handsome bridges between which its expanse is widened. The banks are planted with ornamental trees, and there is an elegant rotunda where musical performances take place. At all times the scene is attractive and animated, but when concerts are given in the rotunda on moonlight nights, the lake is brilliant with an illuminated flotilla, and thousands on thousands of people are scattered about the grass; it is like a picture from fairyland. North of the lake a plantation has become a forest, through which a path leads to an excellently kept cricketing oval, and beyond that Montefiore Hill forms a natural amphitheatre affording ample space for volunteer reviews and the perfection of spectacular effect. Less has been done to beautify the western parklands.

At either end are melancholy adjuncts of civilisation —a cemetery and a gaol; but between them stands the Observatory, and is a suggestion of higher things. South and east are extensive groves developing into forests, and the roads leading in every direction are umbrageous avenues. Ample open spaces are left for recreation, and at the angle a level tract with clumps of eucalypti makes an admirable racecourse that has a spacious grand-stand and every requisite for the English national sport.

Anthony

Trollope complained that the streets of Adelaide were too mathematically exact, but this

peculiarity makes each a charming vista. Many of them are planted with shade-trees, and

looking south or east the hills —which being a thing of beauty are a joy for ever

—make a lovely, background across the intervening suburbs. To the west, when the sun

is low, there is the glimmer of the shining sea, and variety is afforded by the handsome

buildings which crown the North Adelaide hill when the gaze is turned in that direction.

North Terrace is a splendid boulevard entered directly, from the railway station. Looking

westward from that point, the ornamental ironwork of a massive overway bridge leading from

Morphett Street is seen against the sky. Near to it is quaint, old-fashioned Trinity

Church, one of the most ancient ecclesiastical structures in the city. Adjoining the

station to the eastward are the present and future Parliament Houses, the latter of which

is soon to be occupied by the legislature. The fact that while the old building is of

brick, the new one is of South Australian marble, is suggestive of progress. Continuing in

the same direction, King William Street is crossed. Iron gates to the left, high above

which flutters the Union Jack, guard the entrance to the Domain, filled with ornamental

shrubbery, belonging to Government House —an unpretentious but comfortable

two-storey, building. Next comes the Institute, stucco-faced, and behind the times, but

almost adjoining it the Art Gallery, Public Library, and Museum occupy a much more

important-looking edifice. There are a number of good paintings and other works of art;

the reference library contains about fifteen thousand volumes, exclusive of twenty-four

thousand in the circulating library at the Institute, and the Museum is becoming a

valuable collection. These departments are cramped in a structure that is designed to be

the western wing of a building that will be a credit to the city. Beyond an open space

used as a parade-ground, and adjoining which are the police-barracks, drill-shed, armoury,

etc., stands the University, and next to it are the Exhibition Buildings, the central

portion of which is designed to be permanent. It is to be regretted that a little more

artistic taste was not bestowed upon them, for they will suffer by comparison with the

edifices that stand in their neighbourhood. Crossing Frome Road, which leads from Pulteney

Street to the river, what looks like a portion of the original forest is seen away down to

the left. Giant gum-trees of patriarchal age surround a large, low, plain building that

was formerly used for exhibition purposes. Farther on are the Zoological Gardens, just

beyond a gateway into the Botanic Park, from which as well as from North Terrace there is

an entrance into the bewitching gardens that lie —strange and suggestive association

—between the Hospital and the Lunatic Asylum. On the other side of North Terrace, and

near King William Street, is the Adelaide Club-house, lofty and large. Then there is a

long succession of handsome dwellings with trim gardens and bright brass plates, for here

doctors and dentists most do congregate. Chalmers’ Church stands at the corner of

Pulteney Street, and stylish residences alternate with tumble-down cottages, which they

are gradually displacing thence to the stately, pile at the angle of the terraces.

Anthony

Trollope complained that the streets of Adelaide were too mathematically exact, but this

peculiarity makes each a charming vista. Many of them are planted with shade-trees, and

looking south or east the hills —which being a thing of beauty are a joy for ever

—make a lovely, background across the intervening suburbs. To the west, when the sun

is low, there is the glimmer of the shining sea, and variety is afforded by the handsome

buildings which crown the North Adelaide hill when the gaze is turned in that direction.

North Terrace is a splendid boulevard entered directly, from the railway station. Looking

westward from that point, the ornamental ironwork of a massive overway bridge leading from

Morphett Street is seen against the sky. Near to it is quaint, old-fashioned Trinity

Church, one of the most ancient ecclesiastical structures in the city. Adjoining the

station to the eastward are the present and future Parliament Houses, the latter of which

is soon to be occupied by the legislature. The fact that while the old building is of

brick, the new one is of South Australian marble, is suggestive of progress. Continuing in

the same direction, King William Street is crossed. Iron gates to the left, high above

which flutters the Union Jack, guard the entrance to the Domain, filled with ornamental

shrubbery, belonging to Government House —an unpretentious but comfortable

two-storey, building. Next comes the Institute, stucco-faced, and behind the times, but

almost adjoining it the Art Gallery, Public Library, and Museum occupy a much more

important-looking edifice. There are a number of good paintings and other works of art;

the reference library contains about fifteen thousand volumes, exclusive of twenty-four

thousand in the circulating library at the Institute, and the Museum is becoming a

valuable collection. These departments are cramped in a structure that is designed to be

the western wing of a building that will be a credit to the city. Beyond an open space

used as a parade-ground, and adjoining which are the police-barracks, drill-shed, armoury,

etc., stands the University, and next to it are the Exhibition Buildings, the central

portion of which is designed to be permanent. It is to be regretted that a little more

artistic taste was not bestowed upon them, for they will suffer by comparison with the

edifices that stand in their neighbourhood. Crossing Frome Road, which leads from Pulteney

Street to the river, what looks like a portion of the original forest is seen away down to

the left. Giant gum-trees of patriarchal age surround a large, low, plain building that

was formerly used for exhibition purposes. Farther on are the Zoological Gardens, just

beyond a gateway into the Botanic Park, from which as well as from North Terrace there is

an entrance into the bewitching gardens that lie —strange and suggestive association

—between the Hospital and the Lunatic Asylum. On the other side of North Terrace, and

near King William Street, is the Adelaide Club-house, lofty and large. Then there is a

long succession of handsome dwellings with trim gardens and bright brass plates, for here

doctors and dentists most do congregate. Chalmers’ Church stands at the corner of

Pulteney Street, and stylish residences alternate with tumble-down cottages, which they

are gradually displacing thence to the stately, pile at the angle of the terraces.

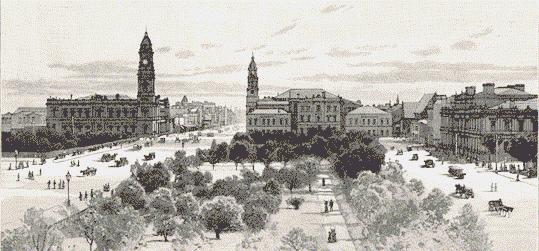

Running right through the city from north to south is King William Street, said to be

the handsomest street in the southern hemisphere. If it is not so, such travellers as

Archibald Forbes and George Augustus Sala have to defend their opinions. It is one hundred

and thirty-two feet wide, has broad flagged footpaths, and contains a number of really

fine buildings, among which those of several banks and the offices of the Australian

Mutual Provident Society are conspicuous. Almost facing each other, and also overlooking

Victoria Square, are the Victoria and Albert towers, the one surmounting the General Post

Office and the other the Town Hall.  Next to

the Town Hall buildings are the Treasury and other government offices, which also face the

square. The block from Pirie Street to Flinders Street is one of the finest in the city.

The municipal premises, including the council chamber, banqueting room, large and

well-proportioned hall, are complete and well appointed. There is a good organ and

fine-toned peal of bells, which, like the tower, were named after the late Prince Consort.

The Post Office is a splendid structure of the Italian order of architecture, built of

freestone, and having frontages of one hundred and fifty feet and one hundred and sixty

feet to King William Street and Victoria Square respectively. It has a large and lofty

central hall, around which the various offices for post and telegraph business are

grouped. The tower rises one hundred and fifty-eight feet from the pavement, and carries a

first-class clock automatically illuminated at night and electrically connected with the

Observatory. Its musical chimes can be heard all over the city, and the striking of the

large hour-bell sometimes five miles away. At the summit of the tower is a carefully

guarded platform, whence a magnificent panoramic view of all the plains of Adelaide, from

the hills to the sea, can be obtained. The intersecting streets divide Victoria Square

into four enclosures planted with trees and shrubbery and enclosed by ornamental iron

railing. To the east is a huge pile of government offices and St. Francis Xavier’s

Cathedral, and on the west are the ornate National Mutual Life Insurance Company’s

buildings. On adjacent blocks are found numerous land and other agencies. The Supreme

Court occupies a conspicuous position to the south of the square, and other law courts are

in the immediate neighbourhood.

Next to

the Town Hall buildings are the Treasury and other government offices, which also face the

square. The block from Pirie Street to Flinders Street is one of the finest in the city.

The municipal premises, including the council chamber, banqueting room, large and

well-proportioned hall, are complete and well appointed. There is a good organ and

fine-toned peal of bells, which, like the tower, were named after the late Prince Consort.

The Post Office is a splendid structure of the Italian order of architecture, built of

freestone, and having frontages of one hundred and fifty feet and one hundred and sixty

feet to King William Street and Victoria Square respectively. It has a large and lofty

central hall, around which the various offices for post and telegraph business are

grouped. The tower rises one hundred and fifty-eight feet from the pavement, and carries a

first-class clock automatically illuminated at night and electrically connected with the

Observatory. Its musical chimes can be heard all over the city, and the striking of the

large hour-bell sometimes five miles away. At the summit of the tower is a carefully

guarded platform, whence a magnificent panoramic view of all the plains of Adelaide, from

the hills to the sea, can be obtained. The intersecting streets divide Victoria Square

into four enclosures planted with trees and shrubbery and enclosed by ornamental iron

railing. To the east is a huge pile of government offices and St. Francis Xavier’s

Cathedral, and on the west are the ornate National Mutual Life Insurance Company’s

buildings. On adjacent blocks are found numerous land and other agencies. The Supreme

Court occupies a conspicuous position to the south of the square, and other law courts are

in the immediate neighbourhood.

The chief thoroughfare for retail business is that immediately south of North Terrace

and parallel with it, extending from west to east along Hindley and Rundle Streets. It is

closely lined with shops from end to end, their continuity being almost unbroken save by

theatres, hotels, restaurants, and lodging-houses. ‘Some of the shops would do no

discredit to any street in the world, and’ the goods displayed in them are of newest

style and best quality. At all times these streets are busy, but on Saturday evenings

locomotion is extremely difficult, and vehicular traffic, except in one direction, is

disallowed. Parallel with them, and farther south, are Currie and Grenfell Streets, in

which, or in some of the cross streets, are found the largest warehouses. In the latter

the Young Men’s Christian Association buildings must attract attention. They rank

about fourth in size and importance among the premises owned by similar associations

throughout the world; and the hall, on an emergency can be made to accommodate a thousand

people. Connecting Grenfell and Rundle Streets is the Arcade-lofty, elegant, lighted at

night by electricity, and for extent and beauty said to be unrivalled in England, America,

or Australia. Shipping agencies, the offices of insurance companies, carriage, implement,

and other factories, are features of this part of the town. In Pirie Street is the

Adelaide Exchange, and in times of mining excitement the corner is occupied by a throng of

brokers. Receding from the centre, ordinary’ dwelling- houses become more numerous,

and also churches and schools. The principal Wesleyan Church fronts the Exchange, and the

Stow Memorial Church stands back to back with it in Flinders Street. Not far away are

Baptist, Presbyterian, Lutheran, and other churches that are both spacious and elegant.

St. Paul’s Church, in Pulteney Street, and St. Luke’s, in Whitmore Square, hold

excellent sites. Large public schools are found in Flinders and Grote Streets, where are

also the training college and practising school.  The City Model School,

built to accommodate a thousand boys and girls, is in Sturt Street, and in Wakefield

Street the Christian Brothers have a large establishment. Rows of cottages are found in

the south and western portion, but on South Terrace and in the eastern quarter are some of

the finest private residences in the city. That there are back-slums and

"rookeries" need not be denied, but they are comparatively few. As a whole, the

city deserves the encomiums so freely bestowed upon it. Its topography and elevation above

the sea enable the system of deep drainage that has been adopted to be applied with

unusual facility and success. The whole of the sewage is conveyed by gravitation along

pipes to a sandy tract about four miles away, where it is applied to fertilising purposes.

The Torrens provides an abundant and excellent water supply, and also furnishes the means

for aquatic amusement. Adelaide has the reputation of being unbearably hot in the summer,

but in this there is not a little exaggeration. The maximum readings of the thermometer

are undoubtedly high, but some allowance should be made for the facts that the bulb of the

instrument is blackened, and it is fixed on a black-board three feet square. No human

being would place himself in such a position unless he were a lunatic. Except for purposes

of comparison, the thermometer might almost as well be placed under a burning-glass. As a

matter of fact, the average temperature of Adelaide is only three degrees above that of

New York —where in winter the thermometer often falls far below zero, so that in

summer it must have a higher range —and the dryness of the heat prevents it from

being depressing. The wide, straight thoroughfares, open squares, and encircling parks

allow the cooling breezes to circulate freely, and they, with the excellence of its site

and beauty of its surroundings, are a perpetual token of the wise forethought of its

founder, Colonel Light. With a sunny sky arching over it for four-fifths of the year,

well-drained and cleansed, and provided with an ample supply of pure water and fresh air,

there is not much room to wonder that it has attained the distinction of being the

healthiest city of the Southern Hemisphere.

The City Model School,

built to accommodate a thousand boys and girls, is in Sturt Street, and in Wakefield

Street the Christian Brothers have a large establishment. Rows of cottages are found in

the south and western portion, but on South Terrace and in the eastern quarter are some of

the finest private residences in the city. That there are back-slums and

"rookeries" need not be denied, but they are comparatively few. As a whole, the

city deserves the encomiums so freely bestowed upon it. Its topography and elevation above

the sea enable the system of deep drainage that has been adopted to be applied with

unusual facility and success. The whole of the sewage is conveyed by gravitation along

pipes to a sandy tract about four miles away, where it is applied to fertilising purposes.

The Torrens provides an abundant and excellent water supply, and also furnishes the means

for aquatic amusement. Adelaide has the reputation of being unbearably hot in the summer,

but in this there is not a little exaggeration. The maximum readings of the thermometer

are undoubtedly high, but some allowance should be made for the facts that the bulb of the

instrument is blackened, and it is fixed on a black-board three feet square. No human

being would place himself in such a position unless he were a lunatic. Except for purposes

of comparison, the thermometer might almost as well be placed under a burning-glass. As a

matter of fact, the average temperature of Adelaide is only three degrees above that of

New York —where in winter the thermometer often falls far below zero, so that in

summer it must have a higher range —and the dryness of the heat prevents it from

being depressing. The wide, straight thoroughfares, open squares, and encircling parks

allow the cooling breezes to circulate freely, and they, with the excellence of its site

and beauty of its surroundings, are a perpetual token of the wise forethought of its

founder, Colonel Light. With a sunny sky arching over it for four-fifths of the year,

well-drained and cleansed, and provided with an ample supply of pure water and fresh air,

there is not much room to wonder that it has attained the distinction of being the

healthiest city of the Southern Hemisphere.

Turn which way we will, there are points of attraction on which it would be pleasant to

linger. The building materials generally used give the streets a bright and cheerful

appearance. There is every adjunct of a high civilisation, and nothing is lacking that can

promote the physical, mental, and moral welfare of the citizens. The numerous spires are a

reminder that Adelaide has been called a city of churches, and yet Earl Carnarvon called

it a city of gardens and flowers. It has its busy hives of industry and spacious halls for

recreation. In the public resorts, cultivated taste has utilised natural advantages to a

degree that always fills visitors with admiration, and sometimes with envy. Of the Botanic

Garden, with its gorgeous masses of bloom, and its collection of plants both rare and

beautiful —its affluent rosary and shady groves of pines, its splendid Victoria Regia

and palm-houses, its graceful fountains and willow fringed lakelets —it is difficult

to write in prose, for it is a poem in itself.  The Botanic Park which adjoins it is to be the Rotten Row of Adelaide, with

miles of winding carriage road through far-stretching avenues of tender green, and among

ancient gum-trees magnificent both in height and girth. It skirts the winding riverbanks,

and in an angle easy of access from the town are the Zoological Gardens, where already the

collection of strange beasts and birds is wonderful, and additions are constantly being

made. As holiday retreats all these are deservedly popular. They are available by all

classes and are visited by multitudes, to the instruction of their minds and the

refinement of their tastes, for they are within five minutes’ walk of the busiest

parts of the city. Scores of other places, with in some respects even superior

attractions, lie within a short radius. Invigorating sea breezes, or the cool climate of

the hills, a dip in the ocean, or a picnic in a sequestered gully, may be obtained at an

hour’s notice. Though the commercial, political, intellectual, and religious centre

of the colony, Adelaide seems to have been planned in the interests of the

pleasure-seeker, and on public holidays the only difficulty is that of choosing in which

direction to go.

The Botanic Park which adjoins it is to be the Rotten Row of Adelaide, with

miles of winding carriage road through far-stretching avenues of tender green, and among

ancient gum-trees magnificent both in height and girth. It skirts the winding riverbanks,

and in an angle easy of access from the town are the Zoological Gardens, where already the

collection of strange beasts and birds is wonderful, and additions are constantly being

made. As holiday retreats all these are deservedly popular. They are available by all

classes and are visited by multitudes, to the instruction of their minds and the

refinement of their tastes, for they are within five minutes’ walk of the busiest

parts of the city. Scores of other places, with in some respects even superior

attractions, lie within a short radius. Invigorating sea breezes, or the cool climate of

the hills, a dip in the ocean, or a picnic in a sequestered gully, may be obtained at an

hour’s notice. Though the commercial, political, intellectual, and religious centre

of the colony, Adelaide seems to have been planned in the interests of the

pleasure-seeker, and on public holidays the only difficulty is that of choosing in which

direction to go.