TASMANIA -

DESCRIPTIVE SKETCH 3 ...Atlas Page 104

By James Smith

RETRACING his steps across the island of Tunbridge, on the main line of railway from Hobart to Launceston, the tourist finds that place situated in the midst of a broad expanse of open country, and surrounded by the evidences of prosperous settlement and active cultivation of a fertile soil. The journey northward by rail lies through a pretty country, and past the handsome mansion which bears the name of Mona Vale; while away to the left the many gables of Horton College attract the eye; and presently the village of Ross is reached, with its picturesquely situated and newly erected cruciform church, as well as one of a much earlier date; its long stone bridge crossing the River Macquarie; and its general air of placid contentment. Campbell Town, the next place upon the line, has also a well-to-do look. At Conaro a branch line to St. Mary’s, a few miles from the east coast, enables the traveller to visit the celebrated Pass just beyond the latter, and also to obtain access to Ben Lomond. The railway follows the curving course of the South Esk as far as Fingal, and from that point runs parallel with one of its tributaries for the rest of the distance. A few miles from Conaro, or the Corners, as it was formerly called, Ben Lomond with its ragged outline looms above all the surrounding ranges on the northward side of the line, while somewhat to the right of it St. Paul’s Dome, with its swelling contour and its forest-clad slopes, offers a remarkable contrast to the naked and high-soaring crags of its loftier and more imposing neighbour. For this is five thousand and ten feet high, while the Dome is barely three thousand three hundred and seventy feet. The one is all amenity, grace of line, and simplicity of form; the other all austerity, angularity and ruggedness of line, and complexity of structure. The Dome seems to have been placed where it is to serve as the noble background of a dozen equally charming landscape pictures having for the elements of each composition green pastures, a brawling stream, and sleek kine coming down to drink of its pellucid waters in the evening light.

But all the attributes of Ben Lomond are those of majesty and grandeur; and perhaps it is never seen to such advantage as at sunrise or sunset. Looking at it at the latter hour from the eastward, when the sky behind is blazing with crimson and gold, and the fleecy clouds which spread out fan-like above its southern ridge are so luminous with reflected light that they seem to invest it with an aureole of glory, the hue of the mountain is that of a pale amethyst which gradually fades into a misty slate colour. The ascent of Ben Lomond is most conveniently effected from Avoca, and can only be accomplished with safety under the direction of an experienced guide. On approaching the foot of the mountain the whole of its southern face presents the appearance of having been laid bare by the severance or subsidence of a now missing slope, thus exposing to view an enormous congeries of basaltic columns, or "organ pipes," some of them rising to a height of seven hundred feet without a break. A "ploughed field," or talus, of shattered pillars slopes away from the base of these; then occur a couple of coal seams, then a thick stratum of silurian rocks, and these rest on a mass of porphyritic granite. Looking up from the Black Rock, near the foot of the precipice, the face of the mountain bears a grotesque resemblance to the ruined facade of a Gothic edifice, as many of the basaltic columns have been sculptured by the hand of nature into cavities that might be easily mistaken for ogival windows, canopied niches, and so forth. The plateau on the summit, which stretches away for a distance of sixteen miles in a north westerly direction, possesses many features in common with a Scottish moor. It is sprinkled with tors and tarns, and there are two lakes, the smaller about two miles from the edge of the escarpment. The larger one is traditionally reported to be fathomless. The view from the highest point of Ben Lomond on a clear day embraces one half of the island, including the whole of the coast-line from Eddystone Point to Spring Bay, with Freycinet’s Peninsula, Schouten Island, and Maria Island. In the opposite direction the prospect is bounded by the Great Western Mountains, and within a radius of fifty miles it overlooks numberless isolated hills, such as Ben Nevis, Mount Saddleback, Tower Hill, St. Patrick’s Head, St. Paul’s Dome, Quamby’s Bluff, and Mount St. John, as well as innumerable valleys, each with its permanent creek, or stream, or river.

Returning to Avoca, the tourist proceeds from that place by rail to St. Mary’s, a township set in a zone of forest and scrolled by heavily-timbered ranges, above which the spire-like peak of St. Patrick’s Head soars sufficiently high to serve as a landmark to vessels far out at sea. St. Mary’s Pass is reached by a winding road almost as pretty in places as an English green lane, and is about two miles distant from the township. From the summit to the foot of the pass there is a zig-zag descent of four miles, through a deep gorge not unlike that of the Via Mala in Switzerland, but on a smaller scale of magnitude. On the right-hand side rises a precipitous ridge of trap-rock, which is being gradually disintegrated by the roots of the forest trees which clothe its rugged sides. On the left the road overhangs a similar precipice, shelving down to where a stream, unseen but not unheard, flows darkling through a cavern of foliage, into which it seems impossible for any ray of sunlight to penetrate. On the opposite side of the gorge there is a corresponding precipitous slope, three or four hundred feet high, thickly timbered to the crown of the ridge, and with that soft purple bloom enveloping its shadowy rifts which seems to harmonise so well with the bright green of the lightwood and the cherry-tree. At various points of the descent glimpses are obtainable of the sea, scarcely distinguishable in colour from the blue sky overarching it. Emerging from the pass, and crossing a sandy flat, the traveller reaches the coast at Falmouth, and proceeding thence by coach in a northerly direction, he skirts an extensive lagoon at Yarmouth, crosses the River Scamander, and keeps the sea well in view until Diana’s Basin has been passed-a saltwater inlet, the title of which is fully justified alike by its sequestered situation and its beauty. From this place it is only a few miles to St. Helen’s, lying at the head of a land-locked bay, ten miles in extent from its entrance to its most westerly arm, and environed by a picturesque country; through which George’s River, fed by many affluents rising in the Blue Tier, conducts its waters to the estuary which bears its name, and is forty miles distant from its source in Mount Albert. Seven miles from St. Helen’s are the Leda Falls, formed by a stream leaping over a huge shelf of granite into a deep gorge overhung by gloomy masses of rock, of the same geological formation, tapestried by innumerable varieties of ferns and creeping plants, and crested by eucalyptus, acacia, and dog-wood trees, intermingled with moisture-loving shrubs. A mile from the falls is to be seen that remarkable mass of granitic rock, forty feet high which has received the name of Truganini’s Throne.

What is known as

Gould’s Country, which must be traversed in order to reach Ringarooma, combines

features which delight the eye of the landscape-painter —an abundance of timber,

large areas of rich and well-watered agricultural land, and extensive stanniferous

deposits beneath the surface of the soil. Thomas Plains present an open expanse of country

irrigated by permanent streams and surrounded by an amphitheatre of wooded hills. There is

a good deal of agricultural settlement in the district, and a Chinese encampment and

cemetery. Its produce, which includes a good deal of tin ore, finds an outlet at

Ringarooma, a town of some importance lying on the edge of a half-moon bay, the horns of

which are fifteen miles apart. It receives the outfall of three rivers, one of which,

bearing the same name as itself, is the most important stream in the north-eastern portion

of Tasmania, and has seven or eight tributaries.

What is known as

Gould’s Country, which must be traversed in order to reach Ringarooma, combines

features which delight the eye of the landscape-painter —an abundance of timber,

large areas of rich and well-watered agricultural land, and extensive stanniferous

deposits beneath the surface of the soil. Thomas Plains present an open expanse of country

irrigated by permanent streams and surrounded by an amphitheatre of wooded hills. There is

a good deal of agricultural settlement in the district, and a Chinese encampment and

cemetery. Its produce, which includes a good deal of tin ore, finds an outlet at

Ringarooma, a town of some importance lying on the edge of a half-moon bay, the horns of

which are fifteen miles apart. It receives the outfall of three rivers, one of which,

bearing the same name as itself, is the most important stream in the north-eastern portion

of Tasmania, and has seven or eight tributaries.

THE capital of the northern portion of the island can be reached from Ringarooma either by coach or steamer. In the former case the tourist is afforded an opportunity of seeing the really magnificent scenery in the district of Scottsdale, and on the other he becomes familiar with the windings of the Tamar, and with the varied succession of charming landscapes which are presented from a continually changing point of view. Launceston lies partly in the arena and partly along the shelving sides of an extensive natural amphitheatre, the various grades of which are thickly dotted with cottages, villas, and mansions, while the higher parts of the town present those inequalities of surface which help to lessen the monotony of rectangular streets. And here, as in Hobart, many spacious gardens pleasantly chequer the surface of the place and beautify its general aspect. Prince’s Square is one of these green oases, laid out in avenues of oak, elm, willow, Pine, and poplar, with a monumental fountain of bronze in the centre, having life-sized figures of the four seasons seated around the plinth of the principal basin, the upper one being supported by four amoretti, locked hand in hand. Overlooking it are some of the principal churches in Launceston —St. John’s, now upwards of half a century old, and containing two handsome stained glass windows, representing "the Ascension" and "the Resurrection," Chalmer’s Free Church, and the Prince’s Square Congregational Church.

The finest prospect of the town is obtainable from either of the

eminences flanking, the gorge of the South Esk. The foreground, with an iron bridge of a

single arch, spanning the broad river at its point of junction with the Tamar, and with

the masses of weather-stained rock piled up in romantic disorder upon each bank, and the

wooden flume which feeds the overshot wheel of an old flour-mill a little lower down

—where "the very air about the door" is " made misty with the floating

meal" —is pre-eminently picturesque. From the banks of the Tamar the town

spreads away to the encircling hills, and every prominent building comes well into view.

In another direction a long stretch of flat country through which the combined rivers flow

seaward, offers a striking contrast to the grander and more distant features of the

landscape; for these include the Great Western Mountains, the Dial Range, and

Quamby’s Bluff in a south-westerly, and Mount Barrow, Ben Nevis, and Ben Lomond, in

an easterly direction, the latter being well seen in profile. The town itself wears a very

bright look, as so many of its public and private edifices are constructed of an excellent

freestone, quarried in the immediate neighbourhood of the place. Among the more striking

of the architectural ornaments of Launceston, are the town hall in St. John Street, a good

example of the classic style, as modified for modern uses by the Italians; the block of

public Offices, in which most of the governmental business is transacted, having a

frontage to the same street, and facing two others; and the mechanics’ institute in

Cameron Street, opposite one facade of the last-named block. This institute contains a

spacious hall with good acoustic properties, and a fine organ; two reading-rooms, a

well-stocked library, an interesting collection of portraits, and a group of the extinct

aborigines of the island, painted by the late Mr. R. Dowling. Close by is the new post

office, constructed of red brick with freestone dressings. Its design embodies some of the

features of the Renaissance epoch of European architecture, and it is one of the most

picturesque of the public edifices of Launceston. The five banks and the Cornwall

Insurance Company are handsomely lodged; and some of the more recently erected of the

churches are creditable to the taste and liberality of the congregations worshipping in

them. A handsome coffee palace and some excellent hotels present a choice of accommodation

for tourists and temporary residents; there is a good theatre, a well-arranged hospital,

an upper class and working men’s club, numerous associations for the promotion of

religion, benevolence, art, music and the drama, agriculture, athletic sports, botany, and

temperance. The visitor soon feels that he is in a town of considerable commercial

activity, and is surrounded by numerous evidences of progress and prosperity. On a

Saturday night the appearance of Brisbane Street, one of the principal thoroughfares, may

well be compared to that of the Kalverstraat in Amsterdam, on a summer evening, so

thronged is it with foot passengers from side to side and from end to end. Launceston is

well provided with open spaces for hygienic and recreative purposes; for, besides

Prince’s Square already spoken of, it possesses the prettily laid out People’s

Park, covering all area of twelve acres, and containing a small zoological collection;

Inveresk Park on the west bank of the North Esk, and five other reserves. It receives a

daily supply of two million gallons of pure water from St. Patrick’s, fifteen miles

distant from the town, and one thousand one hundred and fifty feet above the level of the

sea; and if, at some future time, it should be determined to employ electricity for the

illumination of Launceston by night, there is abundant motive power for the dynamos in the

waters of the South Esk at the second cataract, at no great distance above the outfall of

that river into the Tamar. This romantic waterfall is reached by a zig-zag path on the

south side of the stream, and twenty minutes’ walk brings the tourist to a rocky

knoll from which a fine view is obtained of the rapids as they come foaming down a deep

ravine, and chafing angrily at the obstructions offered to their impetuous course by the

rugged boulders which emboss the channel of the stream. Other ravines are seen opening out

in the folds of the numerous hills, and through each of these a crystal rivulet brings its

tribute to the waters of the South Esk.

The finest prospect of the town is obtainable from either of the

eminences flanking, the gorge of the South Esk. The foreground, with an iron bridge of a

single arch, spanning the broad river at its point of junction with the Tamar, and with

the masses of weather-stained rock piled up in romantic disorder upon each bank, and the

wooden flume which feeds the overshot wheel of an old flour-mill a little lower down

—where "the very air about the door" is " made misty with the floating

meal" —is pre-eminently picturesque. From the banks of the Tamar the town

spreads away to the encircling hills, and every prominent building comes well into view.

In another direction a long stretch of flat country through which the combined rivers flow

seaward, offers a striking contrast to the grander and more distant features of the

landscape; for these include the Great Western Mountains, the Dial Range, and

Quamby’s Bluff in a south-westerly, and Mount Barrow, Ben Nevis, and Ben Lomond, in

an easterly direction, the latter being well seen in profile. The town itself wears a very

bright look, as so many of its public and private edifices are constructed of an excellent

freestone, quarried in the immediate neighbourhood of the place. Among the more striking

of the architectural ornaments of Launceston, are the town hall in St. John Street, a good

example of the classic style, as modified for modern uses by the Italians; the block of

public Offices, in which most of the governmental business is transacted, having a

frontage to the same street, and facing two others; and the mechanics’ institute in

Cameron Street, opposite one facade of the last-named block. This institute contains a

spacious hall with good acoustic properties, and a fine organ; two reading-rooms, a

well-stocked library, an interesting collection of portraits, and a group of the extinct

aborigines of the island, painted by the late Mr. R. Dowling. Close by is the new post

office, constructed of red brick with freestone dressings. Its design embodies some of the

features of the Renaissance epoch of European architecture, and it is one of the most

picturesque of the public edifices of Launceston. The five banks and the Cornwall

Insurance Company are handsomely lodged; and some of the more recently erected of the

churches are creditable to the taste and liberality of the congregations worshipping in

them. A handsome coffee palace and some excellent hotels present a choice of accommodation

for tourists and temporary residents; there is a good theatre, a well-arranged hospital,

an upper class and working men’s club, numerous associations for the promotion of

religion, benevolence, art, music and the drama, agriculture, athletic sports, botany, and

temperance. The visitor soon feels that he is in a town of considerable commercial

activity, and is surrounded by numerous evidences of progress and prosperity. On a

Saturday night the appearance of Brisbane Street, one of the principal thoroughfares, may

well be compared to that of the Kalverstraat in Amsterdam, on a summer evening, so

thronged is it with foot passengers from side to side and from end to end. Launceston is

well provided with open spaces for hygienic and recreative purposes; for, besides

Prince’s Square already spoken of, it possesses the prettily laid out People’s

Park, covering all area of twelve acres, and containing a small zoological collection;

Inveresk Park on the west bank of the North Esk, and five other reserves. It receives a

daily supply of two million gallons of pure water from St. Patrick’s, fifteen miles

distant from the town, and one thousand one hundred and fifty feet above the level of the

sea; and if, at some future time, it should be determined to employ electricity for the

illumination of Launceston by night, there is abundant motive power for the dynamos in the

waters of the South Esk at the second cataract, at no great distance above the outfall of

that river into the Tamar. This romantic waterfall is reached by a zig-zag path on the

south side of the stream, and twenty minutes’ walk brings the tourist to a rocky

knoll from which a fine view is obtained of the rapids as they come foaming down a deep

ravine, and chafing angrily at the obstructions offered to their impetuous course by the

rugged boulders which emboss the channel of the stream. Other ravines are seen opening out

in the folds of the numerous hills, and through each of these a crystal rivulet brings its

tribute to the waters of the South Esk.

Within a short distance of Launceston there is much to

delight the eye of the spectator and to gratify both the artist and the geologist. Near

the Evandale junction on the main line of railway a prospect is obtained of remarkable

extent and beauty, embracing great stretches of yellow cornfields, brown follows, green

pastures interspersed with pretty homesteads, orchards, copses, and gardens, with billowy

hills beyond, and -grand mountain tiers in the distance. A pleasant walk of two miles from

the town will conduct the tourist to the singular basin of greenstone which has received

the name of the Devil’s Punch-bowl, and into which, after a heavy fall of rain, a

slender cataract makes a leap of about fifty feet. About seven miles from Launceston, and

just beyond the pretty village of St. Leonard, lies the glen upon which some enthusiastic

Glaswegian has bestowed the designation borne by the famous falls of the Clyde. There,

however, the chasm through which the stream passes, and which seems as if it had been

riven asunder by some convulsion of nature, is not so deep as the Scottish one, but the

bottom of it is strewn with enormous masses of granite, water-worn for the most part by

the action of the torrent which fumes and frets, and writhes and eddies, and bubbles and

sparkles, but maintains everywhere a delightful limpidity and a delicious freshness. The

almost perpendicular walls of the chasm which are so regularly seamed and laminated in

places as to resemble Cyclopean masonry, are beautifully weather-stained, and are

tapestried with shrubs and creepers. Just below the bridge the gorge makes an abrupt turn

to the right, and in another fifty or sixty yards an equally sudden turn to the left, so

as to resemble the letter Z, after which the banks on both sides drop down to a dead

level, and the river, which was all hurry-scurry a few moments before, subsides into

smoothness and serenity, and gives back peaceful reflections of all the objects on its

banks, among which there are none more beautiful than the delicate flowers of the dark prostanthera

rotundifolia which might almost be mistaken for heather blossoms.

Within a short distance of Launceston there is much to

delight the eye of the spectator and to gratify both the artist and the geologist. Near

the Evandale junction on the main line of railway a prospect is obtained of remarkable

extent and beauty, embracing great stretches of yellow cornfields, brown follows, green

pastures interspersed with pretty homesteads, orchards, copses, and gardens, with billowy

hills beyond, and -grand mountain tiers in the distance. A pleasant walk of two miles from

the town will conduct the tourist to the singular basin of greenstone which has received

the name of the Devil’s Punch-bowl, and into which, after a heavy fall of rain, a

slender cataract makes a leap of about fifty feet. About seven miles from Launceston, and

just beyond the pretty village of St. Leonard, lies the glen upon which some enthusiastic

Glaswegian has bestowed the designation borne by the famous falls of the Clyde. There,

however, the chasm through which the stream passes, and which seems as if it had been

riven asunder by some convulsion of nature, is not so deep as the Scottish one, but the

bottom of it is strewn with enormous masses of granite, water-worn for the most part by

the action of the torrent which fumes and frets, and writhes and eddies, and bubbles and

sparkles, but maintains everywhere a delightful limpidity and a delicious freshness. The

almost perpendicular walls of the chasm which are so regularly seamed and laminated in

places as to resemble Cyclopean masonry, are beautifully weather-stained, and are

tapestried with shrubs and creepers. Just below the bridge the gorge makes an abrupt turn

to the right, and in another fifty or sixty yards an equally sudden turn to the left, so

as to resemble the letter Z, after which the banks on both sides drop down to a dead

level, and the river, which was all hurry-scurry a few moments before, subsides into

smoothness and serenity, and gives back peaceful reflections of all the objects on its

banks, among which there are none more beautiful than the delicate flowers of the dark prostanthera

rotundifolia which might almost be mistaken for heather blossoms.

The important gold-mining district of Beaconsfield can be -reached from Launceston

either by road or river in about -three hours, and the journey either way lies through a

very pretty country. The town itself, which contains about eighteen hundred inhabitants,

lies at the foot of Cabbage-tree Hill. A principal thoroughfare, upwards of a mile in

length, contains all the more important buildings, and exhibits all the characteristics of

a mining settlement.  Seven quartz reefs

are being worked upon, besides three alluvial claims. About five hundred men find pretty

regular employment, and one company has extracted gold exceeding three-quarters of a

million in value, and has divided nearly half-a-million sterling among its share-holders.

At Lefroy, on the other side of the Tamar, there is a goldfield covering an area of a

thousand acres, upon which three companies are engaged in quartz mining.

Seven quartz reefs

are being worked upon, besides three alluvial claims. About five hundred men find pretty

regular employment, and one company has extracted gold exceeding three-quarters of a

million in value, and has divided nearly half-a-million sterling among its share-holders.

At Lefroy, on the other side of the Tamar, there is a goldfield covering an area of a

thousand acres, upon which three companies are engaged in quartz mining.

Returning to Launceston and taking the railway for Formby, the tourist will pass through a tract of country bearing a striking resemblance to some parts of England. This is especially the case with the agricultural district surrounding Longford, where the country seats recall those of -pleasant Herefordshire," and Panshanger, Woolmers, Brickendon, Northbury, Enfield, and half a dozen other residences want nothing but the hallowing touch of antiquity to assimilate them to the "ancestral homes" of the old country. The village itself is situate at the junction of the Lake and South Esk rivers; and the latter is crossed by an iron railway bridge four hundred feet in length. A handsome Episcopalian church built of freestone, stands within a glebe of ten acres, and contains a chancel window of stained glass, and a clock presented by King William the Fourth. Behind the church is the grave of the mother of the first child born of English parents in Tasmania. The chief agricultural shows of the island are held in Longford, and the neighbouring landowners take a lively interest in the promotion of husbandry, and the improvement of the breed of farm stock. A few miles farther on the village of Westbury is reached, with its two handsome churches prominently placed, its orchards and gardens, its hedges of hawthorn, gorse, and sweet briar, and its general air of homeliness, stability, and comfort; while, in the distance, the Great Western Mountains lift their imposing bulk against the sky, connecting in the prospect, the sanctuaries and solitudes of nature with the arts and industries of man: here the soil made fruitful by human toil, the joys of home, the kindly influences of kinship, of neighbourhood and co-operative effort; and there, the loneliness, the solemnity and stillness of the many-centuried forest, with scarcely a perceptible change from age to age.

At Deloraine the railway crosses the river Meander, which does not take its title. The town itself has quite an old world aspect. If the York "high-flyer," or a post-chaise and four, with ancient "boys" in white hats and yellow jackets, were drawn up outside of the squarely-built, sedately-respectable and many-windowed hotels, constructed of warm red brick; or if a person answering the description of the elder Weller were to be found smoking a long clay pipe at the front door, the vehicles and himself would be quite in harmony with their surroundings. Deloraine is surrounded by a fine agricultural country from which its flour-mills, brewery, and tanneries draw their supplies, and it is in the midst also of many country mansions, some of which are worthy to take rank with those in the vicinity of Longford. Ten miles from Deloraine in a westerly direction lies the village of Chadleigh, which had given its name to some limestone caves similar in formation and character to those of Jenolan, but on smaller scale of grandeur, and in the immediate neighbourhood of a mountain of variegated marble. They are about six miles distant from the village, and can be penetrated for a distance of two miles and upwards, presenting the usual features of snow-white stalactites depending from the porous roof, and of stalagmites lifting their fantastic forms from the moist floor, while a subterranean stream wends its way through the darkness of the cavern. In one place the caves are vaulted like a cathedral and the arched roof as well as the walls glitter with phosphorescent gleams. In other portions of this cool retreat, the fibrous traceries seem to mimic lacework in their delicacy and complexity.

Resuming his railway

journey at Chadleigh Road the traveller reaches Latrobe in an hour and a-half, during

which he has had an opportunity of seeing the Mersey gradually expand from a mere brook to

a broad river. The town is the commercial and financial centre of a thriving district,

with numerous churches, banks, stores, and substantial private residences, all bearing

testimony to its general prosperity, and to the confidence reposed by its inhabitants in

the stability of its trade, and the permanence of the resources of the northern portion of

the county of Devon to which it serves as a market town. The Mersey broadens at this point

into a spacious estuary at the mouth of which the rising towns of Formby and Torquay have

established themselves, the former on the left and the latter on the right shore of the

river. Both are favourite places of seaside resort, and the fact that one of them is the

terminus of the western line of railway, and that vessels of moderate tonnage can enter

the estuary at high water, and load or discharge cargo alongside the railway in the Formby

side, is one which serves to explain the unusually rapid growth of the town, which

occupies a picturesque situation at the lowest point of the crescent formed by the

northern coast line of the island.

Resuming his railway

journey at Chadleigh Road the traveller reaches Latrobe in an hour and a-half, during

which he has had an opportunity of seeing the Mersey gradually expand from a mere brook to

a broad river. The town is the commercial and financial centre of a thriving district,

with numerous churches, banks, stores, and substantial private residences, all bearing

testimony to its general prosperity, and to the confidence reposed by its inhabitants in

the stability of its trade, and the permanence of the resources of the northern portion of

the county of Devon to which it serves as a market town. The Mersey broadens at this point

into a spacious estuary at the mouth of which the rising towns of Formby and Torquay have

established themselves, the former on the left and the latter on the right shore of the

river. Both are favourite places of seaside resort, and the fact that one of them is the

terminus of the western line of railway, and that vessels of moderate tonnage can enter

the estuary at high water, and load or discharge cargo alongside the railway in the Formby

side, is one which serves to explain the unusually rapid growth of the town, which

occupies a picturesque situation at the lowest point of the crescent formed by the

northern coast line of the island.

The coach road from Formby to Emu Bay keeps close to the margin of the sea, except where it makes a slight detour inland so as to avoid crossing a promontory; although occasionally its course lies over a low headland, and sometimes it passes along a cornice hewn out of a rugged cliff. Now and then it crosses a brawling stream, hurrying downward fresh and sparkling from the sylvan solitudes in which it has taken its rise, to mingle its waters with those of the sea, which stretches away to the rim of the horizon in the north; and the pungent odour of the vrack upon the shingle blends oddly with the sweet breath of the aromatic shrubs in the bush. Crossing the River Forth at Leith, the coach reaches Ulverston in another hour, where the confluence of the Gawler and the Leven forms a lake-like estuary of singular beauty, set in a dark border of stately trees, with the Dial Range, dominated by its gnomon-like peak, for its noble background. A few miles inland is the reserve of fifty thousand acres set apart by the Tasmanian government, as a settlement for retired Indian officer in the midst of lovely scenery, and with all the advantages of a most salubrious climate. The coach road asses the residence of one of these veterans at Penguin, a comparatively recent township established at the outfall of a stream so named into a pretty little half-moon bay. The inhabitants have placed their city of the dead upon a rocky knoll, overlooking a wide expanse of sea and shore, as if they thought the moan of the waves and the still cry of the sea-birds would constitute an appropriate and perpetual dirge for the departed. Proceeding thence to Emu Bay the road fringes a belt of forestland, with the steep slopes of a range of hills upon the left.

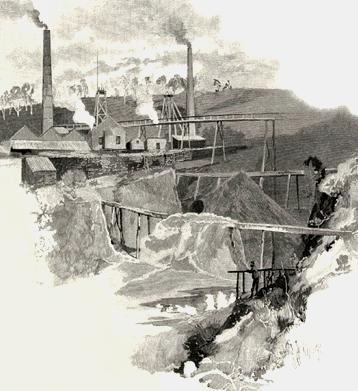

Upon the banks of the Emu River and on the shores of a pretty bay, surrounded by a well-wooded and natural amphitheatre, two townships have been founded —those of Burnie and of Wivenhoe. The former, from the superiority of its position, has overshadowed the latter, and is the port of shipment for the produce not only of the neighbouring districts but of Waratah. This is reached by a railway ascending a succession of ranges and passing through sylvan scenery of the utmost variety and beauty, until the tourist alights in an Alpine township. The population here numbers two thousand souls, and the visitor finds himself close to a mountain of stanniferous stone, which is being gradually broken down, crushed, and dressed, so as to be ready for the smelting furnaces. In these operations some three hundred persons find pretty constant employment. About two thousand five hundred tons of tin ore constitute the annual yield; and Mount Bischoff enjoys the reputation of being the richest tin mine in the world. With a paid-up capital of less than thirty thousand pounds, it has yielded the fortunate shareholders dividends approximating closely to one million sterling. One of the faces of stone laid bare averages a hundred feet in height and something like a thousand feet in width. It reaches to the top of the mountain, and to what depth the valuable deposits may extend can only be matter for conjecture; but to all appearance the profitable working of the mine may continue for a century to come. The whole country, indeed, in a westerly and south-westerly direction, embracing the greater part of the county of Russell and the entire county of Montague, seems to be singularly rich in minerals, comprising gold, silver, lead, till, copper, bismuth and antimony; but the development of its hidden treasures has been hitherto retarded by the wild character of the region, the absence of roads, and the difficulty of exploring it systematically.

One of the steamers calling at Emu Bay, skirting the coast to Circular

Head, enables the tourist to obtain a good view of the chief points of interest on the

way, including Table Cape and Rocky Cape. At the outfall of the river can be seen the

primitive township of Somerset on the edge of the sea, and, a the embouchure of the Inglis

the village of Wynyard, while that of Kellyer clings to the shores of Pebbly Bay. The

remarkable promontory known as Circular Head is a narrow peninsula nearly six miles long,

running, out from the mainland in a northerly direction, and terminating in a bold bluff

about four hundred feet high, under the shadow of which, on the eastern side, lie the

quiet waters of Half-moon Bay. The breezy headland, with the sea on each side of it, and

its extensive outlook along the coast to the east and west, and the picturesque country

behind it, seems to have been destined by nature for a sanatorium, and can scarcely fail

to become such in course of time. Strictly speaking the table-mount which has given its

name to the promontory, is only one portion of it, comprising a plateau of about eighty

acres, and constituting a prominent land-mark for all vessels crossing the Strait from

Victoria. There is plenty of fishing and hunting in the immediate neighbourhood, and much

park-like scenery inland, while the hawthorn hedges near Highfield, the former homestead

of the Van Diemen’s Land Company which owns a large area of country on the north-west

coast, impart a pleasant aspect to the picturesque landscape, so that the tourist in

quitting this beautiful island carries away with him impressions as favourable as those

which he received when he first landed on its shores.

The colony of Tasmania exemplifies better than any other, perhaps, the stages through

which Australian colonisation has had to pass. In the early days, under its primitive name

of Van Diemen’s Land, the colony was the theatre of all that is dark and forbidding

in our early history. On the shores of its quiet bays and water-nooks —as in the case

of Port Arthur —was gathered all the convictism of Britain, and some of the fairest

scenes in the beautiful island were desecrated by the presence of desperate ruffianism,

goaded by official cruelty into excesses which might have amazed even the perpetrators

themselves. The mind is divided in its judgment as to whether, in the old penal system,

the convict or his gaoler is more deserving of the execration of the modern Tasmanian who

reviews the past history of the island. But without pronouncing on this question, it is

safe to say that this page of the island’s story is much better turned down, with

other similar pages that tell of the like disgraceful passages in the history of other

colonies of the Australian group. These things are now no more than disagreeable

historical traditions, and long before Van Diemen’s Land changed its name its people

had begun to move away from these depressing old-time associations. Up to the time of

Governor Arthur, who arrived in 1824, there are no authentic records of early Van

Diemen’s Land. The ruler’s will was his only law. Under such a state of things,

and in a penal colony, the fleeting records we do possess tell only such a story as might

be expected in the circumstances.  From that date up to the

agitation for the cessation of transportation and the establishment of representative

institutions, the history of the island is the record of the conflict between the old

officialdom and the new popular spirit that was then coming into existence. With the

change of name to Tasmania came the bright dawn of better days. The island has progressed

in every direction since then, both socially and politically. To-day its only connection

with the past is the historical link that faintly connects it, as a similar link connects

the mother colony with an episode with which Tasmanians of to-day have no concern.

Favoured as the picturesque little island is by nature, having a climate in which English

fruits grow with native luxuriance, and which is the most pleasant of any enjoyed in the

Australian group, it is no wonder that from all parts of Australia people look to Tasmania

as the fitting scene of a summer’s holiday. The colony is, therefore, the social,

rallying-point in the season, and at such, times Hobart is the place where Australian

society may be seen, under its most charming aspect. Tasmanian social life is famous as

much for the warmth of its hospitality as for the beauty of its women, and the attractive

charm of its pleasant society.

From that date up to the

agitation for the cessation of transportation and the establishment of representative

institutions, the history of the island is the record of the conflict between the old

officialdom and the new popular spirit that was then coming into existence. With the

change of name to Tasmania came the bright dawn of better days. The island has progressed

in every direction since then, both socially and politically. To-day its only connection

with the past is the historical link that faintly connects it, as a similar link connects

the mother colony with an episode with which Tasmanians of to-day have no concern.

Favoured as the picturesque little island is by nature, having a climate in which English

fruits grow with native luxuriance, and which is the most pleasant of any enjoyed in the

Australian group, it is no wonder that from all parts of Australia people look to Tasmania

as the fitting scene of a summer’s holiday. The colony is, therefore, the social,

rallying-point in the season, and at such, times Hobart is the place where Australian

society may be seen, under its most charming aspect. Tasmanian social life is famous as

much for the warmth of its hospitality as for the beauty of its women, and the attractive

charm of its pleasant society.