DESCRIPTIVE SKETCH OF NEW SOUTH WALES

Atlas Page 22

By Francis Meyers,

F. J. Broomfield and J. P. Dowling

W

ESTERN DISTRICT PART 2...South-west from Orange

run some of the head-waters of the Lachlan River, which rise in the Canoblas, traversing

in their course the old mining districts of Canowindra and Cargo, and several fertile

agricultural areas. A good coach road runs to Forbes, which is situated eighty-four miles

distant on the Lachlan River, and along this route a railway line has been surveyed. The

land on either side is capable of supporting a large number of settlers, the climate is

good, and the soil, except in the broad patches of mineral country exceptionally rich.

Forbes was the scene of one of the successful Australian gold rushes Diggers from the

older fields of Young and Grenfell hastened thither; life for a time was wild and

impetuous; miners worked with the excitement of gamblers, and the human vultures that

crowd round successful diggers to ease them of their cash fared well. But when the

alluvial ground was worked out, the excitement all passed away; the wild life has gone,

and the steadier existence of farmers and squatters has succeeded. For a time there was

some doubt whether the soil, rich as it was, would grow wheat but all doubts on that point

have long been settled. With an average rainfall, wheat yields from twenty to thirty

bushels an acre, and oats from forty to sixty; potatoes and maize thrive well, and both

soil and climate seem specially suited to tobacco. Forbes, as the centre of this rich

district, is already a considerable town. It is built on moderately elevated land on the

northern bank of the river, which winds along the edge of a broad and fertile flat. This

is occasionally submerged; indeed, in times of high flood, the river spreads above and

below the town miles wide, filling billabongs and ana-branches innumerable, and storing

water for dry seasons. Any damage done by these floods is abundantly compensated by the

wealth they leave behind them. Rich flats are on either side, of the river, and the

country in the rear yields excellent pasture. Some of the largest sheep stations in the

colony lie between Forbes, Condobolin and Booligal farther down the river —Burrawang

station, about twenty-five miles distant, having a freehold of about two hundred and fifty

thousand acres, and shearing in favourable seasons about two hundred thousand sheep. A

railway line has been surveyed from Forbes to Wilcannia, on the River Darling, the central

township from which roads go north-west and south-west through a dry, but pastoral

district, to the gold and silver bearing country of the Barrier Ranges.

Twenty-two miles

north-west of Forbes is Parkes, a sister town with a very similar origin and history

—first a camping-place in the old pastoral days, then invaded by a rush of

gold-diggers, and then a township with a settled population, depending chiefly on mining

and agriculture. Cudal, nearer to the western line, is another prosperous and pleasantly

situated village; it is twenty-eight miles from Orange, and in the district of Molong. All

these western settlements focus naturally upon Orange, bringing into that healthy and

promising town the produce from their farms, stations and mines. Westward from Orange the

descent from the high land is rapid. Looking from the windows of the railway carriage in

the earlier stage of the journey, a lightly-wooded country is seen sloping away towards

the setting sun; the pasture still green even in the early days of midsummer, the

wildflowers star the grass, and occasionally, almost cover it with their colour and light.

A little lower down and a wash of the more sombre tints of the Australian summer is felt

rather than perceived over all the landscape. The cool fresh mountain air is passing away,

and the heat rises from the plains, now so rapidly approached. Gray-trunked box-trees

sparsely stud the landscape, together with ironbark and gum, and also the beautiful

kurrajongs, closely cropped for food during the years of drought, but bursting with the

first return of rain into fresh and luxuriant foliage. Thirty-five miles on and a thousand

feet down from Orange, is the mining village of Ironbarks, and twenty-one miles farther

the town of Wellington. On either side of the line farms have been established; in dry

years the crop is a failure, but in a good season the soil is wonderfully prolific, though

too often even plenty of rain has its troubles for the farmer, who sees his hay, oats, or

wheat beaten down by a heavy storm just as he was counting on an abundant compensation for

all his losses during the years of drought. Much of the soil is decomposed trap overlying

the limestone and granite at the base of the hills, while the rich alluvial deposits

brought down by the Macquarie and the Bell Rivers cover all the flats. The town is at the

junction of the two streams, and is built on the spot where an outpost of the earliest

pastoral system was established more than half a century ago. Agriculture comes quite up

to the town, the wheat-fields almost at the doors of the stores and mills. The hills,

which are the farthest extending feet of the westerly reaching spurs of the Great Divide,

come down almost to the river’s bank in lightly wooded knolls and open braes, above

which rise craggy and boulder-strewn slopes, with an occasional cone suggestive of the

source of the fertilising trap-rock. The foliage of these hills is more varied than is

usual in the Australian bush. In the caverns and ravines the geologist finds a field for

endless research, for into these limestone caves came, before the human interest of the

world began, those monstrous beasts whose proportions to the animals of to-day are as

those of the sons of Anak to pigmies. The tooth of a diprotodon has been found there with

some fragmentary bones of an echidna —whose complete bulk must have been beyond that

of any of his tribe we know to-day, as much as the New Zealand moa surpasses that quaint

relic of his genus, the apteryx —and a bone of an old-world marsupial, which

Professor Owen pronounces to have been of the lion species. There was large life in

Australia in the days when creatures such as these came down into the mountain caverns to

die. Jungle and forest growths, rivers rolling through broad savannahs, prevailed then

where now is sometimes seen but the dust of drought, and the marsh-film of meagre streams.

The buildings of

Wellington are substantial and comfortable, rather than beautiful; they are all of brick,

and of that deep red tint to which most of the inland clays seem to burn. The hotels are

broad-verandahed and cool, the churches roomy and sombre in aspect, the banks and

insurance offices somewhat ornate and metropolitan in style, and the stores generally of

the old colonial order. Lying grouped in the valley amid the trees by the river’s

edge and the rich foliage of orchards and gardens, they form a charming picture —a

pleasing head and crown to the valley —which stretches on inland for many a mile. The

railway crosses the river by a bridge, the foundations of which were laid with difficulty,

as the engineers had to pierce an enormous stratum of drift —an indication of an old

geologic age. Beyond the town are flat patches of rich green corn, acres of tobacco plant,

and breadths of wheat on a larger scale of farming than is generally seen in the colony.

At Maryvale, twelve miles from Wellington, there are farms of a thousand and twelve

hundred acres all under cultivation, and despite continual droughts, and occasional losses

through heavy rain storms, the farmers are prosperous and hopeful. With intervals of

quartz and granite country, with the usual clothing of stunted forest and scant herbage,

the good soil runs right down the river to Dubbo, thirty miles to the north-west.

Dubbo is ordinarily associated with pastoral work on a large scale, with fierce heats, long droughts, and that old Australian life which knew of little beyond mutton, wool and beef, and the labour by which they are produced. In its earliest days it was the natural business centre for the sheep and cattle stations of the lower Bogan and the Macquarie. A slab-walled, bark-roofed shanty, was the primitive style of building, giving way in the ordinary course of development to the one-storied public-house, with separate ends for squatters and bushmen. It is almost fifty years since the first store was opened at Dubbo, and forty since the earliest holders of Crown grants tried any experiment in agriculture. The drought-proof saltbush was high and dense on all the plains, and the millions of kurrajongs, myalls and mulgas had never been cropped on their lower boughs by the cattle in seasons of distress. Nature’s reserves were sufficient to stand the severest trials, and the only anxiety of teamsters and bullock-drivers even in the driest seasons was to make from water to water. Still a little farming was successfully carried on, the grain was carted thirty tedious miles to the Wellington mill, and back again as flour. But after the Land Act of 1861 many selectors settled on the fertile soil. In 1872 the town had become so considerable that it was proclaimed a municipality and stores, hotel, and banks followed in the wake of the settlers. For a few subsequent years there were abundant rains; the country was full of prosperity and promise; sheep and cattle multiplied on the land. Not only frontages and fertile flats, but back blocks, naturally waterless, were taken up and fully stocked. The fat years passed, a long lean time succeeded —a monotonous drought, broken only by one interval, and lasting for ten years. And yet in spite of heavy losses the occupation of the country has survived the test.

The town of Dubbo is a busy one with enlarging industries, and about it are all the indications of stout-hearted occupation and steady advance. Nor is this surprising, for it is not a village set in a pastoral wilderness, but the farthest western outpost of prosperous agriculture. All down the Macquarie anything from maize to wheat, and from cotton to potatoes, may be grown abundantly. For many miles along its farther course the river consists of a series of basin-like depressions, shut in and divided by bars of rock; at varying distances below its present bed extends a stratum of loose drift or gravel, which, touched by a shaft or boring tube, yields a pure and never-failing supply of water. The township of Dubbo lies within one of these basins, and numerous windmills in evergreen gardens irrigate the thirsty soil. The Dubbo basin was probably at one time a lake or marsh similar to those still existing lower down the river, and which was gradually filled up by the detritus brought down by the higher levels, a narrow channel only being kept open. The surface river is but the visible drainage channel; the permanent waters lie below, saved from pollution and heat by the easily-pierced coating of overlying earth. This underground supply of water has an important bearing on the future of the district, as in addition to meeting all domestic demands, it will furnish enough for a limited irrigation. Every settler can have his well and his windmill, with not only a full supply for domestic luxury, but for the requirements of garden, orchard, and paddock. The area capable of irrigation is large, and the agriculture the future will have wide scope in providing provender for the pastoral stations on either side. Nor does the future prosperity of the town depend on agriculture and pastoral work alone. Coal crops up in the neighbourhood, and on the Baltimore Mountain one seam nearly six feet in thickness has been opened out. The country to the north-west is known to be rich in copper ore, and it is reasonable to look forward to the establishment of a large smelting industry. At present, however, Dubbo is little more than a pleasant village with comfortable cottage homes and the usual commercial and public buildings. The district is healthful and the children thrive, though not with such promise m their limbs, or roses in their faces, as are seen on the table-lands.

As the traveller follows the line of

the railway more to the north-west, he notes that the aspect of the county gradually

changes. The trees fall back, the plains expand, shea-oak belts enclose great flats, where

in good season tall wild oats hide the sheep; the saltbush becomes frequent, and soon

large clumps of lemon-tinted narran are seen, with sandalwood and emu-bush, and then a

flat all myalls and saltbush. On this broad plain the beautiful myall is not only

characteristic, but supreme. It spreads from the railway fence to the dark belt on the

horizon, willow-like in its pendant boughs, with dark trunk and olive-silvery foliage, and

if but a bough be broken, exuding an odour as sweet as that of violets or new-mown hay. Of

all the native growths the myall is the fittest to droop over a grave, to be the in

memoriam tree of Australia, sacred as the yew in England and the cypress in Italy.

As the traveller follows the line of

the railway more to the north-west, he notes that the aspect of the county gradually

changes. The trees fall back, the plains expand, shea-oak belts enclose great flats, where

in good season tall wild oats hide the sheep; the saltbush becomes frequent, and soon

large clumps of lemon-tinted narran are seen, with sandalwood and emu-bush, and then a

flat all myalls and saltbush. On this broad plain the beautiful myall is not only

characteristic, but supreme. It spreads from the railway fence to the dark belt on the

horizon, willow-like in its pendant boughs, with dark trunk and olive-silvery foliage, and

if but a bough be broken, exuding an odour as sweet as that of violets or new-mown hay. Of

all the native growths the myall is the fittest to droop over a grave, to be the in

memoriam tree of Australia, sacred as the yew in England and the cypress in Italy.

The railway line follows the ridge of the watershed between the Bogan and the Macquarie Rivers. The first township of any importance is Nyngan, where the railroad crosses the Bogan, and from which branches off a railway to the west to the mining township of Cobar. From Nyngan the railway rims over a poor, patchy, pastoral country, passing Girilambone, where there are large outcrops of copper ore, which, however, have not yet led to the discovery of profitable mines; past Coolabah —the native name for a full-foliaged handsome description of eucalyptus —and on to Bourke, which is at present the north-western railway terminus. To get a comprehensive understanding of this north-western district, it will be well to follow the line from Nyngan to Cobar. For the whole seventy miles there is hardly a sign of all agricultural or a pastoral homestead. The soil is a light red sand, and patches of scrub are frequent. There is little to be seen but wire fences and sheep clustered about the dams, or camped in the shade of the trees.

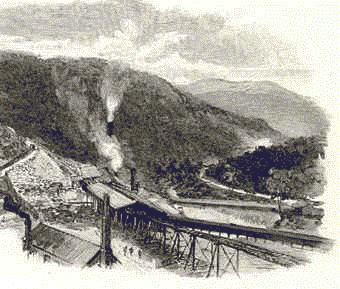

Cobar, a mining township seventy miles from Nyngan, looks an anomaly among the great pasturages —a municipality with mayor and aldermen, courthouse, banks, churches, and schools, out in the midst of the sheep and cattle, the kangaroos and emus, and the wild scrub country. The germ from which the isolated township grew was an outcrop of copper ore —a singular deposit, contained chiefly in a conical hill, on a poorly grassed, lightly-timbered plain. In the hillside is a spring, and stockmen and shepherds were often puzzled by the bright green deposit about the rocks, and the metallic taste of the water. Some practical investigators, attracted by the bushmen’s yarns set themselves to trace out the cause of this green deposit, and very soon came on magnificent lodes of various descriptions of copper ore. A company was formed to work the property, and a township grew with great rapidity. Cornish and Welsh miners were brought up the Darling from Adelaide, furnaces were built, shafts sunk, adits driven, and copper to the value of upwards of a million sterling has already been raised. The primitive buildings were mostly of slabs, pine-logs, or pisÚ work, but many of them have already been replaced by substantial brick structures. A fall in the price of the metal and the difficulty of obtaining fuel for roasting ores and smelting have given a check to the progress of the place. Firewood has to be brought by a tram-line fifteen miles in length, the bush for some distance round having been cleared of timber. The hope of this copper district —for the indications of copper ore are widely spread —lies in railway communication with the coalfields in the neighbourhood of Dubbo.

Beyond Cobar to the west, and running

through much scrub land, is the road to Wilcannia, the river port of the central Darling,

of the Paroo, of the Barcoo, and the Diamantina country of Queensland, of the gold and

silver country in the burnt, bleak Barrier Ranges, and of a great area of rich pastoral

land bordering on and adjacent to the river. Wilcannia has grown up since 1868, being the

best crossing place for stock travelling from the north-western pastures to the Melbourne

and Sydney markets. From being a mere fording township it grew to more importance as the

starting-point to the goldfields of Mount Brown and the silver country to the south-west.

Excellent stone has been found in quarries in the neighbouring hill, and good and

substantial buildings indicate that the old ford is to be a permanent township. A varied

and peculiar traffic is found in Wilcannia. Horse and bullock teams trend through the

streets, and camp on the common every day. The river steamers, constructed for

shallow-water navigation, pass up the stream laden with stores and down with bales of

wool. But novel to Australian bushmen are the camel teams which were introduced in order

to make the journey to the mining districts when two or three days’ stages had to be

travelled without water. From four to eight pairs of these quaint creatures are harnessed

to an ordinary horse-waggon and encouraged by their Arab or Afghan driver, toil with many

a grunt and groan over their weary and arduous journey. Two hundred miles lie between

Wilcannia and the townships of the gold and silver fields —a dreary distance

unrelieved by any pleasant break.

Beyond Cobar to the west, and running

through much scrub land, is the road to Wilcannia, the river port of the central Darling,

of the Paroo, of the Barcoo, and the Diamantina country of Queensland, of the gold and

silver country in the burnt, bleak Barrier Ranges, and of a great area of rich pastoral

land bordering on and adjacent to the river. Wilcannia has grown up since 1868, being the

best crossing place for stock travelling from the north-western pastures to the Melbourne

and Sydney markets. From being a mere fording township it grew to more importance as the

starting-point to the goldfields of Mount Brown and the silver country to the south-west.

Excellent stone has been found in quarries in the neighbouring hill, and good and

substantial buildings indicate that the old ford is to be a permanent township. A varied

and peculiar traffic is found in Wilcannia. Horse and bullock teams trend through the

streets, and camp on the common every day. The river steamers, constructed for

shallow-water navigation, pass up the stream laden with stores and down with bales of

wool. But novel to Australian bushmen are the camel teams which were introduced in order

to make the journey to the mining districts when two or three days’ stages had to be

travelled without water. From four to eight pairs of these quaint creatures are harnessed

to an ordinary horse-waggon and encouraged by their Arab or Afghan driver, toil with many

a grunt and groan over their weary and arduous journey. Two hundred miles lie between

Wilcannia and the townships of the gold and silver fields —a dreary distance

unrelieved by any pleasant break.

But travelling up and down this river when the water is in flood is by no means dreadful. The boats used in the trade are fairly comfortable, with sleeping cabins placed on a hurricane-deck. Towing one or two barges astern, they fight their way manfully upstream, cutting out in times of high flood to ana-branches or side currents, steaming away over tree-tops, and not unfrequently getting hung up or snagged on submerged obstacles. They travel by day and by night, some old river pilots preferring the darkest night as the three or four powerful lights invariably carried show ahead a broad illuminated path, along which it is tolerably easy to steer. But the up-river journey is always tedious; nor is there much charm of scenery to break the monotony. The fringe of eucalyptus is almost continuous, and on the banks beyond spread out the plains —in a good season, green with innumerable herbs and luxuriant grass, and in time of drought covered with brown, grey or red dust, and dotted with bleaching bones. Some distance north of Wilcannia is the little settlement of Louth —a purely pastoral village, deriving all its importance from the stock traffic and the enterprise of the few inhabitants who have shown what the soil is capable of when treated to a little judicious irrigation.

North of Louth is Bourke, the one

historic and characteristic township of the great inland river. Bourke has an Australian

name and fame. It is to the pastoral life what Ballarat is to the mining. The typical

drover, squatter, shepherd, stockman, is as thoroughly identified with the one as the old

time digger with the other, and though in these times a commonplace conventionalism tends

to make men more and more alike, the men who pass through Bourke up and down or who linger

there for a holiday, despite the superior charms of the coastal towns so easily accessible

by railways have many characteristics and peculiarities of their own. The town is built on

a black flat on the left or southern bank of the river —a dead level that stretches

away to the horizon, with a few poor clumps of trees to diversify its bleak and shapeless

aspect. Thirty miles north-east is the remarkable Mount Oxley, rising to the height of

seven hundred feet sheer from the plain, its treeless ridge straight as a roof line. The

red soil is found on the skirts of the black plain, marking the limit of past overflows,

for the river now very rarely rises to the streets of the town. Salt and cotton bush, and

many varieties of river-bank herbage —cresses, spinifex, warrigal cabbage, Darling

peas and native tobacco —grow freely over all the flat, and intrude themselves as

familiar weeds in the gardens and streets and the enclosures of the railway. All the great

buildings —churches, hospitals, schools, banks, and principal hotels are of brick

—the more humble establishments and the cottages are of galvanised iron, sawn pine,

or the various materials ingeniously applied to back-block architecture. The streets are

broad, but unmetalled. In a dry, hot day of midsummer, black dust, as fine as flour, blows

along them. In a wet day of winter the sticky mud clings to all things with which it comes

in contact —boot soles, buggy wheels, the hoofs of horses. The traveller finds

himself in a few minutes walking in clogs, so quickly does the plastic mass grow beneath

him. The experienced resident keeps within doors, holding fast to the common creed that

there was never yet so much hurry in Bourke that a man need go outside when it rained. And

indeed there are not many wet days in Bourke. Winter months bring occasionally piercing

winds, the thermometer standing at 50░. Summer is unmistakably hot, the mercury, even in

the shade, often ranging from 110░ to 125░. It is not the place in which a mail favoured

with a choice would choose for a residence, and yet the regular inhabitants, with the

frequent visitors, seem to live with tolerable comfort and health, though in a way of

their own. From the balcony of either of the large hotels by the river, where most of the

life of the town focuses, or passes by, much that is interesting and peculiar may be seen.

The larger hotels, after the old colonial style, are divided into two parts —this the

squatter’s side, that the bushman’s. There are of course characters of all

sorts, and some are steady and sober, but too many of the bushmen, stockmen, shearers,

boundary riders, drovers, steamboat men, all drink together, get drunk, lie upon the

benches, get sober, go down to the river for a swim, "get broke" —or, in

more intelligible phrase, spend all their earnings —and clear out for work again.

The squatters —old fellows, inured to bush

life and lost to all desire of the city, and young fellows only a year from the coast, but

all of the fine coppery hue which a year of the Darling still puts on —lounge about

the other side. The business of the day seems to be to lounge, to drink at intervals, to

yarn continuously, to speculate on the prospects of the season, and, without ceasing,

though in their own fashion, to pray for rain. The townsfolk go about their business

leisurely enough. Bankers, public officials, and others keep for awhile a metropolitan

style, but not beyond a single summer; the languor of the hot north changes their manners

before they change the cut of their clothes. The two great businesses in Bourke are the

carrying of goods and the purveying of drinks. Every second shop seems to dispense

liquors, and happily, since the completion of the railway, many varieties of drinks are

brewed from the lemons and oranges and ice brought up by the daily train from the coast.

Bullock teams, horse teams and American coaches come into the town from all points of the

compass and in the busy season the streets are lively with shearers with packhorses, and

swagsmen with all their estates on their backs, steamboat hands, and drovers from the

Warrego, the Paroo, and the Bulloo.

The shearers may have left their mountain homes at Monaro in midwinter, may travel a couple of thousand miles, do good work, and then reach home again by harvest. The swagman may have walked the length and breadth of these colonies; but the river men live, and hope to die, on the water. The drovers are the busiest and perhaps the most interesting of all fellows who live at least sixteen hours out of the twenty-four in the saddle, who bring down the big mobs of cattle from the rich pasturage of western Queensland, truck them at the yards a couple of miles out of the town, enjoy in their own way their loose day or two, and then make back again. Strange experience this for the cattle —creatures as wild as buffaloes, who on their native pastures would bolt from a man who should venture near them unmounted; yet not less than fifty thousand are trucked every year, long trains with the living freight starting citywards every day. In the near future this live stock traffic may end, and a great slaughtering and freezing establishment may be at work on the edge of the great pastures. If this anticipated change takes place, Bourke may develop somewhat on the lines of Chicago.

Nor is it necessary that the produce of the district should be confined to wool and meat only. A glance at the Chinese garden irrigated by an engine and a Tangye pump, lifting water from two wells, shows that the soil will grow anything —peaches, grapes, oranges, oats, cotton, tobacco, maize, and all sorts of vegetables. Three miles east of Bourke the river is bridged, and from that bridge the roads branch off to the border, and over ten degrees of longitude to the great downs of Queensland and the Northern Territory of South Australia.

To the north lies the country of the

springs, a remarkable tract running between the Warrego and the Paroo, where the water

breaks right through to the surface —sometimes through a stratum of pipe clay,

bearing up so much of that easily-soluble substance as to be undrinkable and valueless, at

others from a stratum of unsalted drift, through limestone or ferruginous rock,

overflowing pure limpid cool; giving birth to a verdant grass and reed growth, and making

a rare oasis on the plain. Beyond the springs lies a poor scrubby country, with a sparse

supply of spinifex, and before the rich downs of Queensland are reached is Barrigun, where

ultimately great Queensland overland line will join that of New South Wales.

To the north lies the country of the

springs, a remarkable tract running between the Warrego and the Paroo, where the water

breaks right through to the surface —sometimes through a stratum of pipe clay,

bearing up so much of that easily-soluble substance as to be undrinkable and valueless, at

others from a stratum of unsalted drift, through limestone or ferruginous rock,

overflowing pure limpid cool; giving birth to a verdant grass and reed growth, and making

a rare oasis on the plain. Beyond the springs lies a poor scrubby country, with a sparse

supply of spinifex, and before the rich downs of Queensland are reached is Barrigun, where

ultimately great Queensland overland line will join that of New South Wales.

Brewarrina is seventy miles east of Bourke on the left bank of the river. It is somewhat similar to the latter both in architecture and design and anticipates a like future. To the north, towards the Queensland border, it commands a country infinitely superior to the background of Bourke —at least twenty thousand square miles of rich black flats, broken up by occasional sand ridges traversed by the four creeks, which receive the waters of the Queensland Balonne, and discharge into the Cato (a branch of the Darling) and the Narran Lake. There are great possibilities in this country, but as yet enterprise has been only primitively pastoral. The waters run to waste in floods, the plains bake and burn in times of drought; a few tanks indeed have been excavated, a few dams made on the creeks, but nothing adequately to meet the terrible exigencies of a climate whose fat and lean years come almost as regularly as those foretold by Joseph in Egypt.

The aspect of this great country is not wanting in the picturesque; the mirage is frequently seen in perfection —trees inverted in phantom lakes, sheep in the distance looming like advancing armies, swagsmen taking on gigantic proportions, and seeming at times to rise suddenly from the earth. Here also is seen that peculiar phenomenon of the lifting or expanding horizon at sunrise and even. In the heat of day, all around seems bare, bald, plain; the range of vision being limited by the refraction of heated air, but just at dawn or evening the traveller familiar only with the daylight aspect, is astonished to see long lines of black timber by various lagoons and creeks, the serrated crest of a pine ridge with the dark and tangled woods below, horses and bullocks an hour’s ride away and emus and kangaroos making down to the water. All are swallowed up, and with almost equal rapidity, in increasing light and darkness. Many varieties of timber trees also are found here quite foreign to dwellers on the high lands of the coast. The ghostly brigalow grows in thorny clumps on the poorest ground, the gidya bears a broad and shady crown with bunches of pale yellow blossoms malodorous in the extreme; the leopard-tree lifts its quaint spotted trunk, and here is found the beef-wood, which shows on its cleavage a grain strongly resembling that of a broad-cut steak. Mulga, myall, and yarran are abundant and, as undergrowth, there are all varieties of salt and cotton bush, and an infinite variety of succulent herbs.

Farther up the river is Walgett, the permanent head of the Darling navigation; and from Walgett there is a good coach road to Coonamble and thence to Dubbo. Walgett is an important town, and most favourably situated with respect to general convenience of trade. It is accessible from the northern as well as from the western lines, and does also a very considerable business with the country beyond the river both its rivers are bridged, and an effort has been made to make both navigable but the snags in the Namoi proved too formidable even when covered by the highest flood.

Coonamble, a hundred miles down the Castlereagh River almost due south of Walgett, touches again on the agricultural country. The future of the town depends on the development of the agricultural resources, which are scarcely inferior to those of Dubbo. Indeed the soil here, east, west, north and south, is adapted to tillage; but the alternating years of terrible floods and disastrous droughts is disheartening to any but well sustained and strongly supported effort.

A hundred and ten miles of coaching through as fair a pastoral country as any squatting prospector could desire, brings the traveller from Coonamble back to Dubbo.

Creeks and rivers are frequent

throughout the journey —all that network of streams from the Namoi to the Bogan,

which water some of the finest stations the colony knows —a glorious country in a

rainy spring, a terrible scene of desolation in a dry summer. Agriculture attacks its

southern skirts, and supports such little, townships as Warren and Cannonbar; but all its

northern breadth is given over to sheep, and probably will be held exclusively for sheep

through many future years. But it may be so developed and improved by water conservation

and irrigation by the reservation and storage of the extra growth of good years, as to be

habitable and tolerable, and ultimately profitable through any succession of seasons or of

cycles.

Generally speaking the western and north-western portion of New South Wales constitutes a district distinctly marked out by Nature as having its own special character. Hitherto it has been purely pastoral, except so far as it has been interfered with by mining adventurers. In a state of nature the country is not very occupiable any distance back from the Darling. When first taken up by speculative pastoralists the land was only available for grazing purposes for half the year, and not even that unless there had been an average rainfall. But by dint of much labour in increasing the water supply, many large districts have been made pasturable all the year round. For increasing this water supply two methods have been adopted. The first has been to gather the surface water, and this has been done by selecting natural hollows, deepening them and running plough furrows towards them. In this way, the surplus rainfall is collected into large earthen tanks. The soil excavated makes a high bank around, and this breaks the play of the wind over the water and diminishes the evaporation. Many tanks of this kind, however, have been prepared for over three years before rain enough fell to fill them.

The other method of storing water is by sinking wells. The subterranean supply has these two advantages; it is cooler, and it is not exposed to evaporation. Generally, however, it has to be pumped to the surface, and the wells are costly to make and to maintain. Scores have been sunk without tapping water at all, and in many other cases the water has been too salt for use. The enterprise of the squatter is often rewarded by a well which never falls even in the driest season. In fact, the well is quite independent of the local rainfall, for the water pumped up in the Darling basin has fallen first upon the western plains of Queensland, and having soaked in there is pursuing its underground course to the sea.

The natural fodder of the great west consists of grass and the various salsolaceous plants. The former, however, exists only a short time after rain, the intense heat soon turning the green herbage into something resembling live hay, after which it dries up into chips and powder and is blown away by the wind, leaving the ground as bare as a road. Yet with all these drawbacks the country has been not unprofitably occupied, for it is remarkably healthy, both for sheep and cattle; the squatters, who in the main have been a highly enterprising class, have already done much to protect themselves against the irregularities of the climate, and every year they are learning more and more the art of turning the great western country to account. Forbidding as the land looks to a stranger in the bad season, this vast district is a very valuable province of New South Wales.