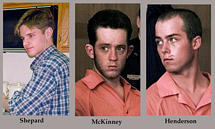

LARAMIE, Wyo. (AP) — Matthew Shepard went to high school in Switzerland. He spoke three languages and had traveled the world. He was raised in a close, loving family made comfortable by his father's job in a multinational oil company. At the University of Wyoming, he was studying political science.

LARAMIE, Wyo. (AP) — Matthew Shepard went to high school in Switzerland. He spoke three languages and had traveled the world. He was raised in a close, loving family made comfortable by his father's job in a multinational oil company. At the University of Wyoming, he was studying political science.

Aaron McKinney and his friend, Russell Henderson, came from the poor side of town. Both were from broken homes and as teen-agers had had run-ins with the law. They lived in trailer parks and scratched out a living working at fast-food restaurants and fixing roofs.

The three, each 21 years old, were brought together from different worlds in a savage crime that has shaken the nation into another agonizing appraisal of its attitude toward gays.

As attention focuses on the murdered man's sexual orientation and calls go out for more legislation to protect gays, some see it also as a crime of class hatred in a divided prairie town that defies some of the stereotypes of the West and has missed out on America's high-tech economic boom.

``Sooner or later this was going to happen in Laramie,'' says the Rev. Stephen M. Johnson, leader of a Universal Unitarian congregation here. ``This is going to happen again and again and again unless the have-nots of this town become part of the community again.''

The ferocity of the attack on Shepard became evident on the evening of Wednesday, Oct. 7, when Aaron Kreifels, a college freshman, fell off his mountain bike in deep sand and prairie scrub and noticed what looked like a scarecrow dangling from a barricade of lodgepole pine.

But this was not a farm, no place for a scarecrow. The barricade was there to seal off a 14-room luxury house under construction. And it was no scarecrow but a young man, barely alive, with white nylon cords holding up his 5-foot-2-inch, 105-pound frame.

His skull had been gashed in four spots. His nose was broken. The skin on his head and face was cut in 18 places. Some cuts went to the bone. He had been pistol-whipped and left hanging there for 18 hours.

He died at a hospital in Fort Collins, Colo., early Monday from head injuries.

Two days after the attack, police arrested McKinney and Henderson, and Laramie's shock was complete. Many had believed, or wanted to believe, that such things couldn't happen here, in a town of 26,687 where cars and homes are routinely left unlocked, where bank tellers know customers by first names. Now Laramie was the focus of national outrage.

———

Laramie has a split personality typical of many university towns.

On the east side is the University of Wyoming's ivy-clad main campus, where students drive sports cars or stroll and bike along oak-shaded sidewalks.

On the opposite side of town, a bridge spans railroad tracks to another reality, of treeless chocka-block trailer parks baking in the heavy sun, fenced-off half-acre lots, stray dogs picking for scraps among broken stoves, refrigerators and junked pickups.

Unlike the university students, youths on the west side have little in the way of entertainment; no malls, no organized dance troupes, no theater or playing fields. On weekends, many teen-agers hop into pickup trucks and drive across the scrublands to the Snowy Range forest area to drink beer and party.

Unlike the university students, youths on the west side have little in the way of entertainment; no malls, no organized dance troupes, no theater or playing fields. On weekends, many teen-agers hop into pickup trucks and drive across the scrublands to the Snowy Range forest area to drink beer and party.

In Wyoming, nearly 1 in 10 workers holds three or more jobs to make ends meet. In Laramie, 20 percent of the population lives in poverty and young people are often left on their own by day and night.

And an increasing number, including Aaron McKinney and Russell Henderson, are running afoul of the law.

McKinney was born in Laramie on Aug. 2, 1977, on the wrong side of the railroad tracks.

His parents divorced when he was 5, and his mother, Denise, left him for days on end with his grandparents. When grandparents weren't around, his mother would lock him in a basement for hours, friends of the family said.

Four years ago, after his mother died from complications following a hysterectomy, he received a large cash settlement in a wrongful death case, and, according to friends and relatives, went on a buying binge.

By September, he had all but squandered the money on jewelry, partying, and loaning large sums to friends. He bought a Mustang car, crashed it, bought a white Camaro. He got vanity plates with his nickname, ``Dopey,'' but within a year, his license was revoked.

From then on, Aaron McKinney's run-ins with the law became more frequent and serious. He was arrested for shoplifting in 1990, but the charge was dismissed; Later, he was fined for speeding, driving without insurance, driving without a license, underage drinking.

In December, he and several friends broke into a fast-food restaurant after closing time, taking $2,500 and dessert. He fled to Pensacola, Fla., with Kristin LeAnn Price, his pregnant 17-year-old girlfriend. There he worked as a pipe fitter for $1,000 a month until police caught up with him. He returned to Wyoming and pleaded no contest to burglary charges, his first felony.

|

He was awaiting sentencing when, after nightfall Oct. 6, he and Russell Henderson walked into the Fireside Bar, a popular college hangout where students, straight and gay, mingle with locals.

The two friends shot pool, drank a few beers. When it came time to pay their tab, they rummaged for coins in their pockets, then looked up. Drinking alone at the other end of the bar was a clean-shaven young man wearing dental braces and dressed in a sports coat, khaki pants and patent leather shoes: Matthew Shepard.

There are conflicting accounts of how Shepard and his accused attackers met. Some witnesses say he offered to help them pay their tab. Others claimed he made advances to them.

The three were seen walking out of the Fireside Bar together sometime before midnight.

———

Russell Arthur Henderson's background is superficially parallel to his friend Aaron's: His mother left him with aunts and his grandmother, who runs a day-care center out of her backyard in Laramie.

Shy, pleasant, diligent — ``a wonderful boy,'' his grandmother once said — young Russell never stood out among his peers. Several of his friends remarked that he was friendly, though distant at times — a ``follower, and a polite, polite kid,'' in the words of Carson Annenson, his landlord. Shy, pleasant, diligent — ``a wonderful boy,'' his grandmother once said — young Russell never stood out among his peers. Several of his friends remarked that he was friendly, though distant at times — a ``follower, and a polite, polite kid,'' in the words of Carson Annenson, his landlord.

Henderson had several gay and Hispanic friends in a community that is 93 percent white. ``The gay issue had never been an inkling of a concern,'' Annenson said.

He earned 21 merit badges to make Eagle Scout and got his picture in the newspaper for it. He played high school volleyball, basketball, football and soccer. He was regularly on the honor roll.

He never mentioned his mother, though, not even to friends he had known for 10 years. ``I asked him once where his parents were. He said his parents were dead,'' said Maggie McKinney, 23, who lived next door to Henderson.

His troubles worsened soon after he moved out of his grandmother's house four years ago: He had several petty charges against him, from drunken driving to having an altercation with a police officer.

At 15, he was working at the Taco Bell fast-food joint a block off the college campus. He met a girl who was two years older but broke up a year later when he learned she was heading to college to study art.

``He was jealous because she was going to college, and he was still in high school. He always wanted to go to college, you see, and he knew he never could afford it,'' said a friend and co-worker.

Later, he shared a rusting trailer with another girl, Chasity Vera Pasley, 20. She cleaned motel rooms, he found odd job as a roofer, handyman and home remodeler.

They spent nights around a brick campfire in front of the trailer, roasting marshmallows and drinking beer, setting off firecrackers after midnight, lighting small fires to the scrub brush in his yard, and blaring loud ``thumping'' music from his car stereo. ``He always had an attitude, a bad one,'' said Cheryl McKinney, who lived in a trailer next door. She remembered him as a ``spoiled brat, a snotty little thing'' who was pampered by his grandmother.

Mrs. McKinney, who was unrelated to Aaron McKinney, had a feeling Russell and his friends weren't going far in Laramie.

It's the same story for all of the young people in her neighborhood, she explained. With no college degree, the only work in town pays $5.65 an hour, stuffing fajitas, flipping burgers and making beds in motels.

Many ranches in the prairie scrub around Laramie have no jobs because they have no cattle, she said. Openings at the one industrial plant, a cement factory, are hard to get, and Wyoming is rated the state with the fewest technology-related jobs.

Ralph Castro, director of the Drug and Alcohol Prevention Center in Laramie, believes the crime was more a robbery than an anti-gay assault. ``There is always going to be people living near the poverty level in town, and others with high-profile jobs. I have no idea how we are going to prevent something like this from happening again. That's the million dollar question and something that everyone in Laramie, Wyoming, and the nation is asking.''

———

Anti-gay sentiment would occasionally bubble up in Laramie — before Shepard's death, at least — manifested by young men driving past the campus shouting ``we're going to kill you!'' followed by anti-gay epithets, according to residents.

During the past week, students at the University of Wyoming have held candlelight vigils. People have gathered at churches along Grand Avenue, the tree-lined avenue in front of the college, praying for reconciliation and atonement.

Few of the mourners, however, come from the rundown west side.

By TODD LEWAN

The Associated Press

Oct. 17, 1998 |