The Martial Way

A personal interpretation of the Japanese martial arts by

Ernest F. Lissabet

|

Budo The Martial Way A personal interpretation of the Japanese martial arts by Ernest F. Lissabet |

|

| Beginnings… Budo and Balance… Budo and Specialization… Form vs Realism… About Kendo & Iaido, Part I… Kendo and Kumdo… Thoughts on Kyudo... Thoughts on Naginata… Concerning Isshu-jiai... Batto-do: Kendo and Iaido, Part II Federations, Politics, & Promotions… Conclusions |

Dr. William "Bill" Dvorine, Yon-Dan Kendo and Iaido, Founder of the Washington Kendo Club, father of Kendo in the mid-Atlantic region of the United States, and a Director of the Greater Northeastern U.S. Kendo Federation; Dr. Donald "Don" Seto, Yon-Dan Kendo, Founder of the old Northern Virginia Kendo Club at George Mason University, and a Director of both the Northern Virginia Budokai and Greater Northeastern U.S. Kendo Federation; Ms. Fran Vall, Yon-Dan Naginata and Go-Dan Judo, Founder of the East Coast Naginata Federation, and a Director of the Northern Virginia Budokai; Mr. Gregory "Greg" Huff, Roku-Dan Renshi Muso Jikiden Eishin Ryu Iaido, Ni-Dan Karate, and Founder of the Northern Virginia Eishinkai; Mr. William "Bill" Reid, Yon-Dan Kyudo, Founder of the Northern Virginia Kyudokai, and a Director of the Northern Virginia Budokai; Mr. David "Dave" Drawdy, Ni-Dan Batto-do, Command Sergeant Major, U.S. Army (Ret.), a Director of the Northern Virginia Budokai, and chief Batto-do Instructor of the Budokai by permission of Guy Power Sensei, Roku-Dan Renshi & designated "Kaicho" (Administrator) of the Nakamura Ryu in the United States. Mr. Shozo Kato, Nana-Dan Kyoshi in both Kendo and Iaido, President of the Shidogakuin Kendo Clubs in Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Washington DC, and Miami Florida; former Coach of the U.S. National Kendo Team; and a Director of the Greater Northeastern U.S. Kendo Federation. Mr. Dan DeProspero, Roku-Dan Renshi, Founder of the Meishin Kyudojo in North Carolina; Co-Author (with Hideharu Onuma Sensei) of Kyudo: The Essence and Practice of Japanese Archery; and President of the American Kyudo Renmei; Mr. Maruyama Chikao, Ju-Dan Hanshi Muso Jikiden Eishin Ryu Iaido, Founder of the Eishinkan Dojo in Saga City, Japan; President of the Zen Kyushu Iaido Renmei; and third-ranking Iaidoka of the Muso Jikiden Eishin Ryu. |

Kendo, "The Way of the Sword" or Japanese fencing (Gekken), in which I am a "Ni-dan" or second degree "black belt." Zen Nihon Kendo Renmei, and All United States Kendo Federation. |

|

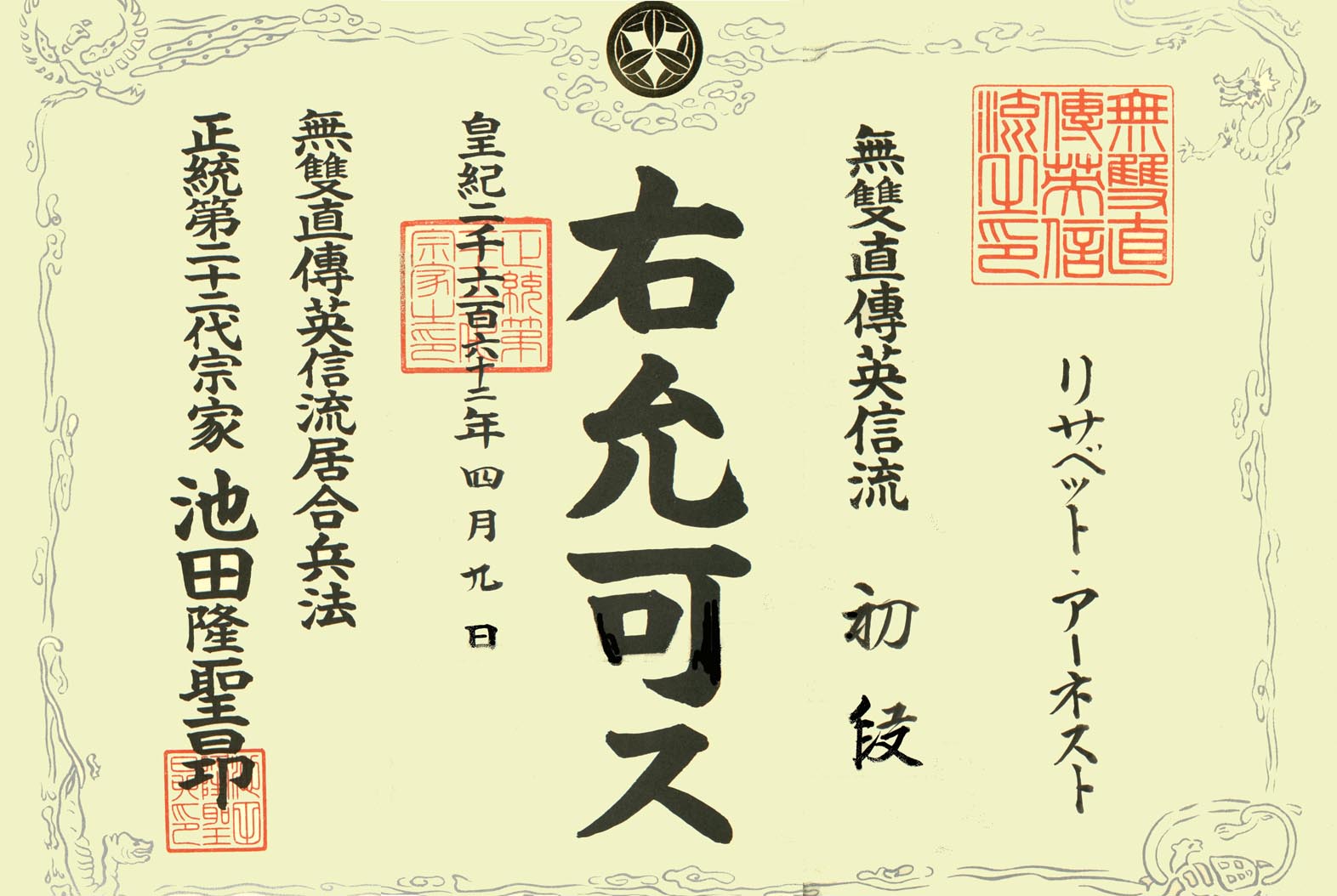

Iaido, the art of swordsmanship, in which I am a Sho-dan

in the "Muso Jikiden Eishin Ryu" style of swordsmanship, or "Peerless Direct Transmission True Faith School." This style of swordsmanship is one of the "Koryu" or "old forms," and has a 450 year old lineage. I am also studying Nakamura Ryu Batto-do, a military form of Iaido in which Tameshigiri (cutting practice) is integral to the curriculum. |

Naginata, the "reaping sword," the modern art of

pole-arm fencing based on "the curved spear" of the Japanese middle ages, in which I am a Sho-dan through the Zen Nihon Naginata Renmei, and a member of the United States Naginata Federation. |

|

|

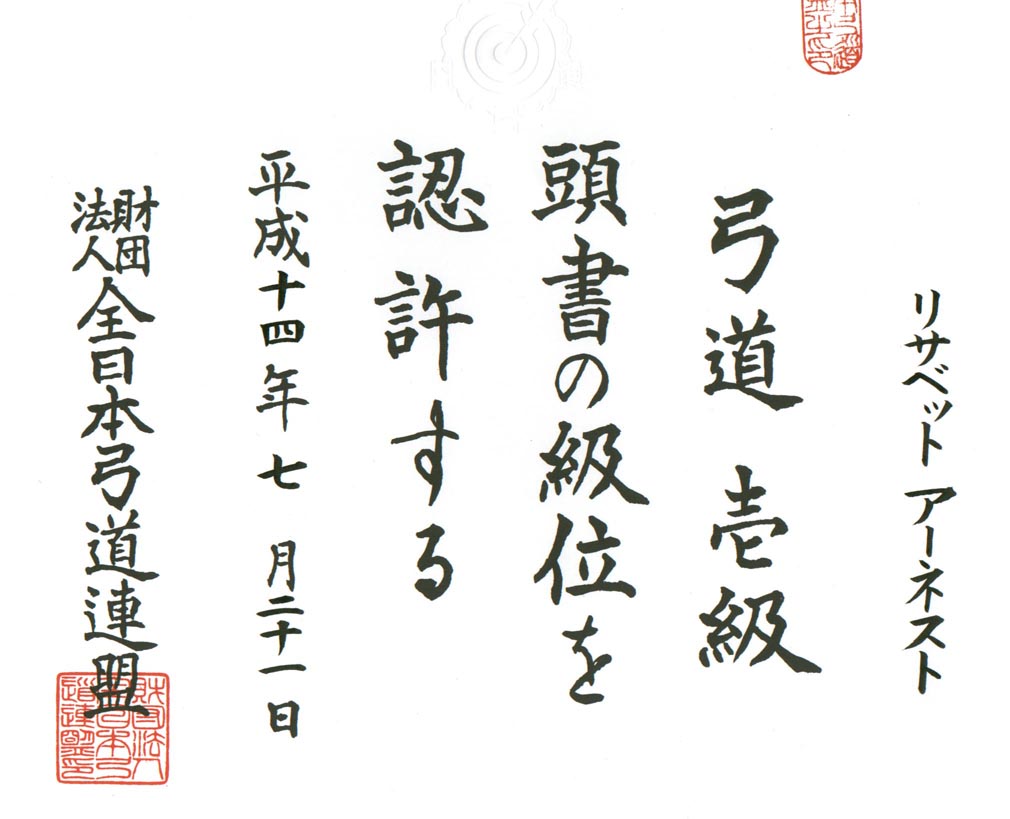

I am also a Sho-Dan in Kyudo, the art of Japanese

archery. The certificate illustrated here is for Mudansha rank, as I've not yet scanned my Sho-Dan certificate. The photo at left is also of me shooting at an early stage of my Kyudo training... I hope my current form is a bit more accomplished than this. Of all the forms of Budo I study, Kyudo is without question the most elegant and beautiful. |