When I tell most people that in the very early sixties, the United States exploded a very powerful hydrogen bomb virtually over the island of Oahu in the Hawaiian Islands, they find it difficult to believe.

As a teenager of fifteen my dad was stationed in Hawaii in the Air Force. We lived in a place called Ewa Beach some six or eight miles to the west of the entrance to Pearl Harbor -- a perfect vantage point to see "the bomb".

Scientists told us through the media that we would probably see a flash, high in the southwestern sky and warned us not to observe it through binoculars or telescopes since it could cause eye injuries. It was to detonate high out of the atmosphere to be launched on a Thor rocket from Johnston Island 800 miles to the southwest of us, and we *probably* would see a flash of some kind -- it might be worth watching, and blah, blah, blah. Someone miscalculated in their predictions of the "yield" of that bomb. Little did we know that we would behold a most awesome event.

During several days in June we would listen to the radio only to hear that the mission had failed, or had been scrubbed. Finally in early July we gathered at the sea wall at Ewa beach. We listened on our transistor radios as a voice counted down the last several seconds. At precicely 11:00 pm the voice reached 0 seconds.

And then the bomb went off !

Patrick Mahon dawg@gate.net

There is a related link at the bottom of the story.

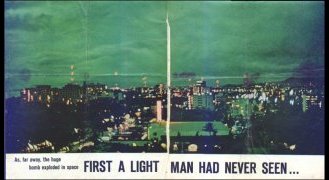

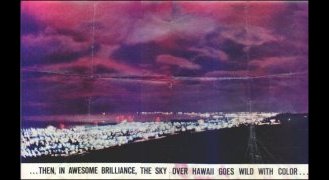

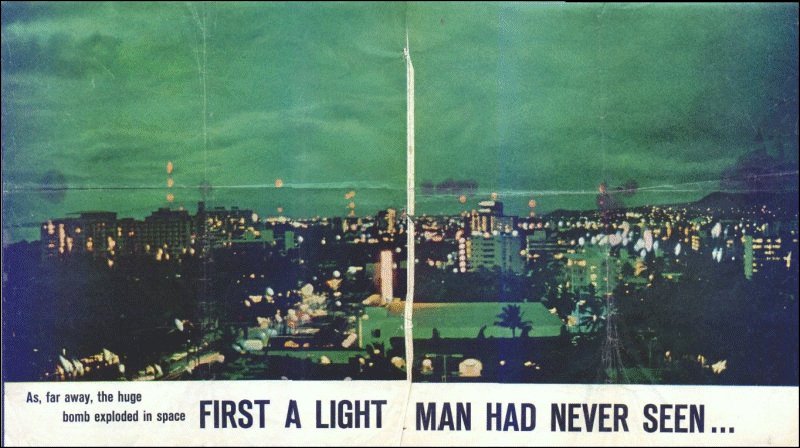

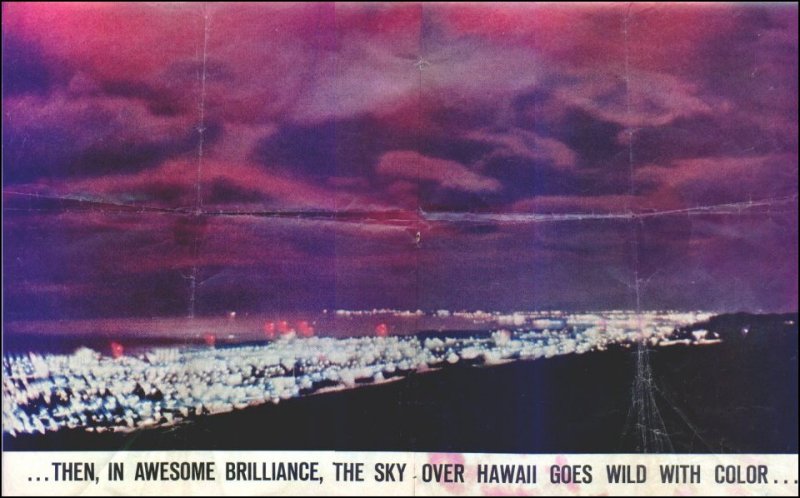

The following article and photos are taken from an original copy of Life Magazine vol. 53. no. 3 July 20, 1962

... 'IT WAS AS IF SOMEONE HAD POURED BLOOD ON THE SKY'

For time before the memory of man, the night sky rose unreachable above him. Its dark dome reflected only the pinprick of stars, the moon's changing face, the aurora's subtle glow, the jagged webs of lightning. But now man was no longer a mere observer of the sky. He had tumultuous lightnings of his own. Last week he loosed them, exploding a giant hydrogen bomb hundreds of miles in space over the Pacific. As the incredible flash spread over millions of square miles of ocean man looked up in awe and wonder at what he had done.

In the Hawaiian Islands rain dripped from the rattling palms on the

day the shot was to go off. The clouds were thick. Hawaiians, recalling

nine postponements and two failures in earlier attempts to send up the

bomb, saw the gray sky and concluded that nothing would happen this time,

either. Of the earlier low-level shots they had seen nothing at all.

But at noon short-wave radio sets began to pick up monotonous voices

broadcasting time checks from Johnston Island 800 miles to the west, launching

site for the Thor rocket which would thrust the H-bomb aloft. Gradually

word spread that another countdown had indeed begun. Later in the

afternoon weather, scientific, and observation planes began taking off

from Hawaiian airfields, headed west. After dark as the crowds started

gathering along the reefs Life regional editor Dick Stolley joined them.

"There were coeds in muumuus, college boys in swimsuits, tourists in newly

purchased resort wear, sleepy kids. Some carried transistor radios to keep

track of the countdown." On Waikiki Beach boys brought their dates. In

Pearl harbor, sailors drew up in orderly row on the dock alongside their

submarine. A showgirl from the Royal Hawaiian Hotel slipped outdoors in

her ti-leaf skirt, hoping to see the shot between acts. Other spectators,

seemingly undisturbed by the symbolism, watched from a cemetery. The weather

grew worse and veteran observers began to expect another postponement.

But at 10:45 the word came that the Thor rocket was off the pad and rising.

Honolulu radio stations cut their programs and broadcast the continuing

countdown for the explosion as the rocket climbed for 15 minutes. Stolley

heard the remote counting voice from Johnston Island "grow higher, almost

girlish." It read off the final five seconds. Then it was precisely 11

o'clock.

Life correspondent Thomas Thompson was watching from a hotel courtyard. "The blue-black tropical night suddenly turned into a hot lime green. It was brighter than the moon. The green changed into a lemmonade pink and finally, terribly, blood red. It was as if someone had poured a bucket of blood on the sky." Stolly on Waikiki Beach saw the blast as "white and hot, like the flash of a breaking electrical circuit. It turned almost instantly to bright bilious green, a color so unexpected that watchers on the beach gasped. Great green fingers of light poked out through the clouds. From the center of the blast, a red glow began expanding upward. It was not the familiar orange of a tropical sunset but a deep, solid red, and the people afterwards groped for words to describe it. The glow bubbled aloft and boiled in the sky. A quarter-moon -- some people thought it was the fireball --glowed through occasionally as the clouds broke and its face glowed not pale but a rich, strange yellow."

Some 2000 miles southwest from Hawaii, Life Photographer Carl Mydans watched from the island of Samoa. There were no crowds. Mydans and another newsman stood alone in a deserted mountain pass, and saw what Mydans called "the greatest rainbow in history ... First two bright lines came up off the northern horizon, curving away from each other, looking like feathers in a glass. The white lines of the earth's magnetic field curved round from north to south and in between them were colored lights dancing. After six to eight minutes the rainbow faded but it left something behind I'd never felt with rainbows: elation, awe, and unearthly fright."

In Hawaii there was the same fear. One family had kept its children up late to watch from the beach. The parents saw their kids staring wide-eyed at the tormented sky and they shuddered. Another elderly couple covered their eyes. Most of the watching crowd was silent. "There was none of the go-team-go atmosphere of a missile launch." Stolley reported. "The crowd stood strangely still, as if braced for a thunderous of noise. There was no noise, of course, and we constantly had to remind ourselves that what we gaped at was taking place 800 miles away. We stood there with only the gentle sounds of the sea and civilization murmuring around us."

As tests go, the man-made inferno was supremely successful It was a crucial part of our effort to deter a nuclear war by keeping our nuclear superiority. The Pacific blast may lead to better weapons for us -- and perhaps even a defense against enemy missiles. It came at a time when we seemed to be triumphing wholesale in tests of strength and skill with nature: digging canyons in the earth with other nuclear blasts in Nevada; orbiting an intricate star which brought pictures from one side of the Atlantic to the other with the speed of light. But the scientific and technical importance of the events seemed to pale in the bright fury of the blast which climaxed them. There were prayers all across the Pacific last week -- prayers across the world -- that man's headlong mastery of his universe would always stay as wondrous, and as safely remote, as on the awesome night the we set the sky on fire.

Seconds after the blast the sky glowed a bright green. Note that

it is 11:00 at night in this photograph, although it looks as if it is

dawn.

article

thumbnails

Photo published in July 1962 Life Magazine taken several minutes after

the blast. The sky remained this way for perhaps 20 minutes and then transitioned

to dull orange.

article

thumbnails

Spectators gape in the searing light.

article

thumbnails

Above Samoa 2000 miles away

article

thumbnails

back to the top

A related story from a recent Honolulu Star Bulletin article

http://starbulletin.com/96/06/18/features/story1.html

An excellent page covering the entire series of tests

http://www.aracnet.com/~pdxavets/dominic.htm