11/ The Triton

A Little Gem

TRITON (MK 1):

Length overall:

28 feet 4 inchesLength on waterline:

20 feet 6 inchesBeam:

8 feet 4 inchesDraft: 4 feet

Sail area:

371 square feet (sloop)Displacement:

6,930 poundsDesigner: Carl A. Alberg

Year designed:

1958When the Triton class was introduced at the New York Boat Show in 1959, it was an immediate sensation. The trim little 28-footer was one of the early cruising sailboats to be made of fiberglass, and it is now considered a classic. Many a sailor who had been undecided about what boat to buy must have made up his mind on the spot after a look at the boat show sample, because 16 orders were placed at the show.

My uncle, Charles E. Henderson, a stern critic of stock designs, had spent over 20 years looking for just the right boat. His sons, Ed and Charlie, had all but given up hope that he would ever do anything but window shop, but he finally did decide to buy a Triton. Of course, he didn't buy her immediately-the inevitable bugs

in any new design had to be ironed out first-but he determined that this was the right boat, and eventually the cautious Scotsman plunked down his money. Neither he nor my cousins, who did .most of the sailing, ever regretted the choice.Occasionally, I sailed with my cousins on their Triton named

Ojigwan, and I'll never forgetcompeting in an early spring series held at Oxford, Maryland. The competition was rough, because we were up against two of the top racing sailors on the Chesapeake Bay: Bill Meyers, sailing a Morgan-designed Columbia 31, and Doug Hanks, sailing a red-hot Cal 28.

Ojigwan was well prepared, with a beautiful new suit of sails including an oversized main that could be flattened and reduced a bit in fresh winds with Cunningham cringles and a foot lacing line. Charlie decided that standard bottom paints were not fast enough, so he mixed up and applied his own concoction, which turned out not to be very good as an antifoulant but made the boat slippery as a greased eel for several weeks.The series was a tight one, but Ojigwan came out on top, and it showed me firsthand that a well-tuned Triton could sail with the best of her contemporaries, including fin-keelers and centerboarders. We were at a distinct disadvantage when sailing downwind because of the threequarter rig and tiny spinnaker, but the Triton could usually recoup her losses on the upwind legs

.

Charlie was the usual skipper, but on one race when he was away, I filled in for him. We got off to a good start and led Hanks by a few boatlengths to the first mark, which was Bononi Point lighthouse. There was a riprap of rocks surrounding the lighthouse, and Hanks, a native of that area, yelled a warning that there were some underwater rocks we should keep clear of. In my naivet6 of Eastern Shore gamesmanship, I gave the mark a wide rounding, and this gave Hanks a perfect opportunity to slip inside us and take the lead. Actually, there really were rocks under the water, and Hanks had done nothing at all unethical, but I was too cautious, and as a result, we were plainly outmaneuvered. We never could regain the lead, but Ojigwan finished close behind the Cal 28 and easily saved her time to win the race, despite my lack of finesse.

The Triton is not only a smart sailer, but she's a good looker. Her designer, Carl A. Alberg, to my knowledge never drafted an ugly boat. He had previously designed such well-known attractive craft as the Coastwise Cruiser, when he worked for the John Alden Company, and much later the saucy little Sea Sprite that resembles the Triton in some respects. It would seem impossible to get six-foot headroom in a boat only 21 feet on the waterline without ruining her appearance, but Carl Alberg pulled it off with the Triton. He did this by using a high but attractive doghouse, so there was no need to detract from the looks of the hull with excessive freeboard. Of course, the trouble with a tall doghouse is that it is hard to see over, but this difficulty can be alleviated, if the helmsman is not too short, by sitting on a seat, even one or two cushions.

Pearson Yachts of Rhode Island built the Triton, and it might be said that the Triton built Pearson Yachts, for the company was reportedly in, bad financial shape before it began producing the popular Alberg design. Even though this particular class is no longer produced, many hundreds of Tritons were sold, and this gave the company a much-needed boost. In fact, the late Everett B. Morris, a highly respected yachting reporter, once wrote that the Triton allowed Pearson Yachts to narrowly "escape from the oblivion of bankruptcy."

To my regret, Grumman Allied industries, Inc., of which Pearson Yachts is a division, refuses to release the lines of the original Triton, despite the fact that the boat has not been produced for many years and the designer is more than willing to have the lines published. However, Mr. Alberg was kind enough to draw up, especially for this book, a new set of lines that might be labeled the Triton-Mark II. This plan closely resembles the original boat, and in one respect the Mark 11 lines more accurately resemble the actual late-model Tritons, for Mr. Alberg wrote me the following: "Starting with boat #385, Pearson put the lead keel inside the hull, which of course made the keel almost two inches thicker and about one inch deeper. This change is incorporated in this plan." The Mark 11 plan also differs from the original lines in that Mr. Alberg "straightened the upper part of the stem line, increasing the overall length by two inches, from 28 feet 4 inches to 28 feet 6 inches; lengthened the aft end of the LWL two inches by making a slight change in the profile of the lower part of the stern overhang; and gave the rudder a more modern shape."

The hull is certainly beautifully shaped, to my eye at least. There seems to be just the right amount of overhangs with the bow and stern nicely matched but with sufficient waterline length for speed in a breeze and also to inhibit hobbyhorsing. The keel is long enough to give directional stability and to supply ample lateral plane for the sake of minimizing leeway. A shorter keel would reduce wetted surface, of course, but it might require more draft to supply the same lateral resistance, and this would not be helpful to gunkhole cruising. The Triton's hull is fairly symmetrical by modern standards, and her waterlines are rather straight amidships. These characteristics, together with her modest beam and generally moderate proportions, give her an easy, predictable behavior unlike so many of today's temperamental racing cruisers. Her sections show fairly firm bilges, and this feature, together with a 44 percent ballast-to-displacement ratio, enables her to carry her sail well in a breeze.

Although the Triton is rather small for offshore work, it is a good sea boat. Triton number 8, named Ole, made a rugged trip from New York to Bermuda in 1960 and came through a bad Gulf Stream storm unscathed. The early models, however, need certain modifications before going to sea. On those boats, for instance, the cockpit seat lockers open from the side rather than the top, and the standard unhinged locker doors could leak or possibly be washed out by a sea breaking into the cockpit. But if the lockers can be kept sealed, there is little danger from a filled cockpit, because the well is quite small. in fact, I read that Carl Alberg once calculated that a full cockpit would "only" lower the stern 51/2inches.

Another shortcoming of the early Tritons was that they came with single rather than double lower shrouds, and a number of masts were lost as a result. It is my understanding that after boat number 120, however, another set of lower shrouds was added, and shroud kits were supplied to the earlier boats.

Most Tritons are sloop rigged, but some were rigged as yawls. Personally, I can't see much advantage in having two masts on such a small boat. The mizzenmast can be used as a backrest, of course, and it is fun to hang up a mizzen staysail, but that sail has a very narrow range of effectiveness. The standard three-quarter sloop rig is very efficient on the wind, but as mentioned earlier, it is not advantageous for downwind handicap racing. Some Tritons were fitted with slightly shorter than standard masts and were masthead rigged, but for some reason these boats did not seem to do as well in closed-course racing. Two Tritons of my acquaintance were fitted with bowsprits to extend the base of the foretriangle, and one of these boats did extremely well despite the fact that she might have had some lee helm in light airs.

Back in 1959, when the Triton was first introduced, many sailors were amazed at the room below. They had been used to the cabin of a wood boat with ribs and ceilings that seemed to shrink the interior. Nowadays, in this age of fiberglass, the Triton doesn't seem so large; but nevertheless, she is roomy for a boat only 21 feet on the waterline and with a beam of 8 feet 4 inches. Also, she is well laid out with four full-sized bunks 6 feet 3 inches long, a head that can be closed off, and plenty of stowage space. Her wide beam forward allows sufficient foot room for the forward bunks. On many boats of this size, the forward bunks converge into a V, and this means that the sleepers compete for foot room. About the only drawback to the accommodations is that the galley is quite small, and there is not much of a place for a proper stove. Some owners have solved this problem satisfactorily by using a bulkhead-mounted Sea Swing that burns Sterno or kerosene. Another very minor problem is that the 221/2-gallon water tank is located on one side of the boat, which could cause a slight list when it is topped up, but it is somewhat counterbalanced by the ice box on the opposite side.

A friend of mine used to own a Triton named Gern. I always thought the name was most appropriate, because that's exactly what the boat is, a little gem in the world of molded stock designs

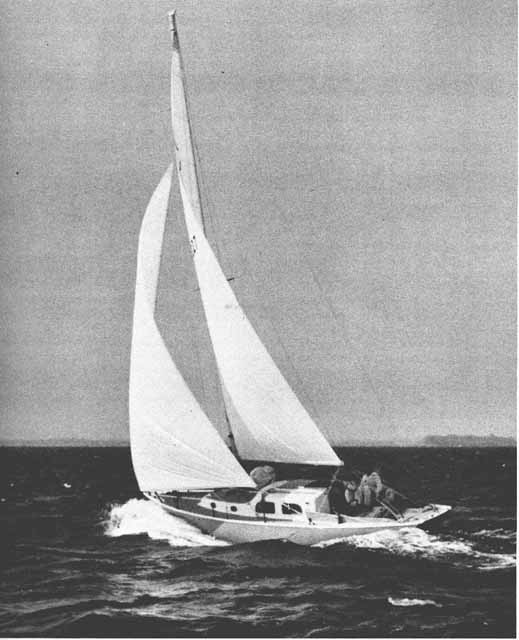

With her tall mast, large mainsail, andfractional rig, the Triton sloop has a very handy and efficient sail plan. Such a rig will allow some flexing to flatten the main in a breeze, but it would be important to use great restraint, because the mast was not designed to bend very much.

(The Skipper)

About the only thing lacking in the Triton's accommodations is a stove, but a portable one might be used on the drop leaf when at anchor and a bulkhead-mounted swing stove can be used underway. (The Skipper)

Ojigwan II in the fall of 1962 with the author at the helm and Ed Henderson manning the windward rail. The vang at the end of the main boom is a makeshift substitute for a traveler. (Fred Thomas)

On a spinnaker run in light airs, the Triton is at a disadvantage, because her 'chute is so small. In real drifting conditions, however, the small 'chute can often be kept filled when larger ones collapse. (Fred Thomas