PRE-CHRISTIAN BRITISH RELIGION

Its Evidence, Suppression & Survival

Introduction

From the word 'religion', we must banish such concepts as the formal extraneous splendour and efficiently formulated inner structure of ancient Egyptian temple worship, the state-blessed Roman pantheon with deities identical in name and form in every colony of that illustrious empire and the well established hierarchic and functional web of the Roman Catholic Church with its welter of dogmas, interdependent doctrines and dogmas which, although originally a unifying umbrella of security for both system and worshipper, was to become the reef of disunity effecting diversification within the Christian Faith and the hiving off of the various sects which are prevalent today.

What must be retained, however, is the simple explanation of the term 'religion' - belief in unseen power which governs the cosmos, piety and practical reverence, all being qualities born and matured on inner-plane levels. By this I mean born of or inspired by Spirit, not of state decree or Church council, matured by the peaceful contemplation of mind rather than by synod or conclave and manifested, not by the awesome extravagance of Gothic architecture, but subjectively in the emotions to issue forth as benign practicalities in one's outward existence and in the interaction with one's peers on the myriad strata of socio-economic human function.

We ask then, "Could

such a simple process exist independent of state or regional organisation?

Indeed, did such a natural process exist?" Let us attempt to answer

the latter question, which subtends the former, by the examination of two

areas of evidence - the first archaeological, the second historical.

Archaeological Evidence (general)

Perhaps we should commence the evaluation of the archaeological evidence by reappraising the finds in the proximal regions of the continent of Europe where dwelt the Palaeolithic kindred of our insular ancestors.

The remains of Aurignacian cave-shrines, together with artefacts dating from c. 20,000 to 12,000 BC, still exist in the Dordogne area of France and have their counterparts in Kelt Iberia (Spain). It is interesting to observe that many of these are some considerable distance from what were the day-to-day dwelling sites of the people and, therefore, appear to be loci set apart and possessing some aura of sanctity. As caves are indeed natural retreats of physical safety, it may be too obvious that the Palaeolithic tribes were motivated solely by the primal instinct of self preservation to utilise them as such.

A far less obvious and perhaps overlooked factor in the isolation of one particular cavern as a sacred shrine may well be that on the subliminal level of the primitive mind was a compelling attraction to the two greatest mysteries faced daily - the mysteries of birth and death. I firmly believe that, in addition to the gregarious or 'herd' instinct in humankind and those of self preservation and reproduction, there can be found a further two - instinctive behaviour relating to mentation and spiritual evolution. If we bear in mind the concept of a divine spark or spiritual nucleus indwelling each human individual (no matter how primitive he be) as is upheld by most religions, can we then really deny that an inbuilt driving force exists to permit this nucleus to progress by distillation in the fire of human experience.

As a contemporary example which reinforces this hypothesis, we note that, in our own era of supposedly advanced civilisation, this inner motivation to reach out to the unseen at the Gate of Birth or the Gate of Death, thereby obtaining some measure of spiritual uplift, may still be perceived even in the most degenerate of our peers. Too many instances are seen as a 21st century norm on this debased stratum of society when in an ill directed way the mindless indulge their unbridled sexual promiscuity on the one hand and their violence and brutality on the other, thereby coming as near to the two gates as possible within the framework of society's ethics and laws, thus obtaining the desired uplift or 'kicks' as they are wont to describe the experience.

In view of this motivation, therefore, the cave must have been symbolic of the womb and the Cavern of Death, both of which be portals in the boundary between the world of mankind and the realm of divine cosmic power where all mysteries lie. Where, however, is the definite link between these caverns and religion?

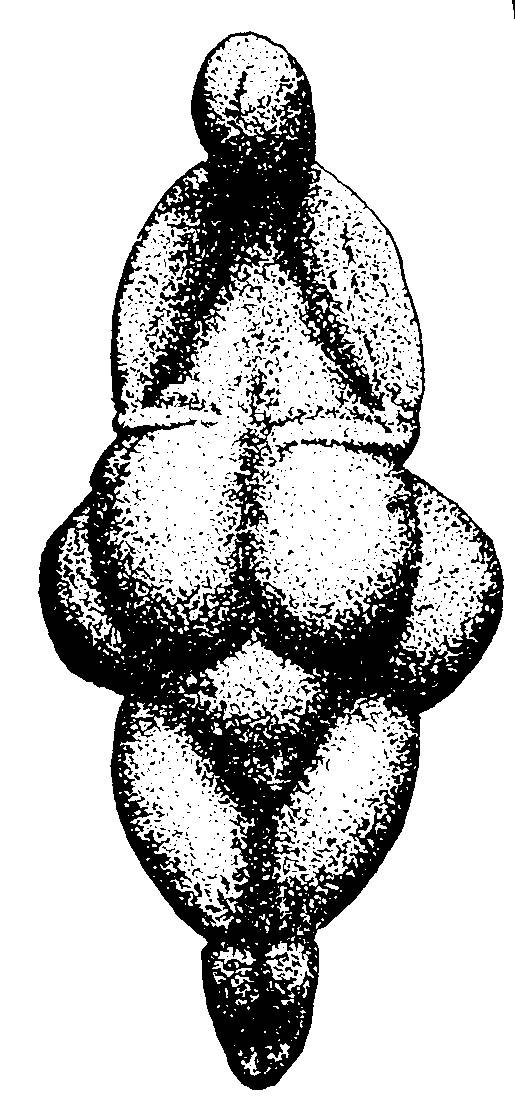

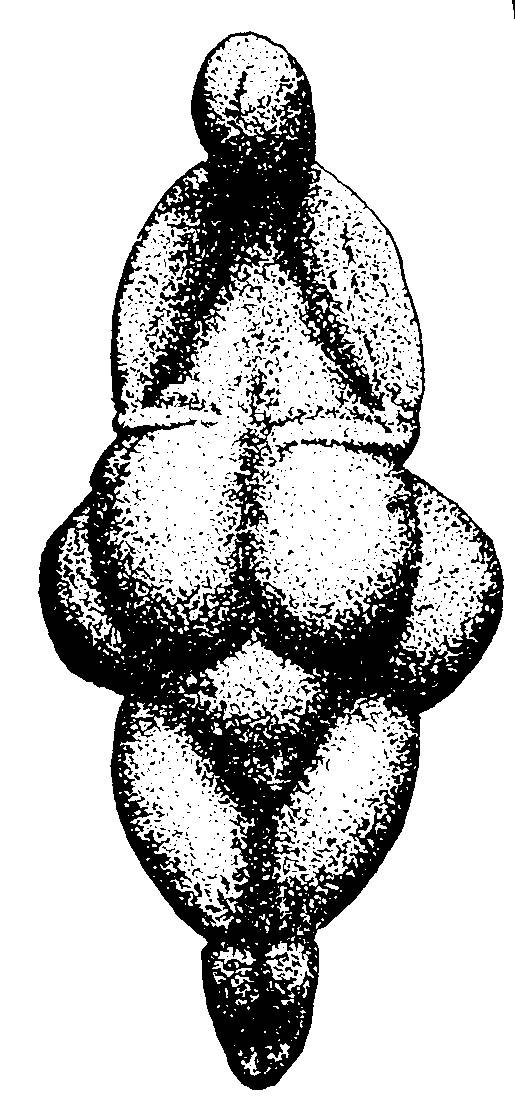

Let us examine the

appearance of some of these loci such as the caves at Laussel and Ariège

and the multi-chambered cavern of Lascaux. When first discovered,

many cave shrines revealed a circle of stones which retained traces of

fire some one half mile from the entrance. Figurines of the female

form carved in ivory or stone depicted grossly exaggerated breasts, genitalia

and abdominal distension suggesting advanced stages of pregnancy.

Within the same circles, paintings of animals upon flat stones and effigies

of animals pierced by small spears were in abundance. Here four factors

emerge and are obviously linked.

In considering the second factor first, we find fertility essential and of utmost importance at that epoch, for without abundance of young, the herds and, therefore, food and clothing would diminish. Without abundance of children, the tribe would become depleted, weakened and endangered.

We must now attempt to understand the importance of woman in this primitive social structure, an early germ of thought whence matriarchy was to spring.

Woman was regarded as the vessel of human fertility and life and, therefore, the keeper or embodiment of the mystery of birth for as yet it was not understood that sexual congress with a male was the sine qua non of conception - after all, a woman did not conceive every time she lay with a man. So, being the guardian of the mystery of birth, she was considered to be in closer proximity to the unseen forces behind the Mysteries and, therefore, well able to mediate between humankind and these forces or High Gods as they were to become.

This is clearly portrayed in some early cave art work where the woman is painted much larger than the man and, in one particular painting, with a line from her genitals to a hunter who is engaged in shooting arrows at game. Her natural power to bring forth is obviously being projected to the hunter that his labours of the future bear fruit. In this painting the woman's arms are upraised in an invocative posture which demonstrates that the artist was recording the generally accepted belief of the people - the woman's power was obtained from The Unseen via the tool of invocation.

Here a point is reached where, in addition to woman who cooks and supplies nourishment from her hand, woman who gathers the herbs and tends the sick and ailing, woman who guides the development of the children, woman who prepares the dead for burial and woman who brings forth in birth, there is now woman the invocant who brings power and force through to manifestation and is, therefore, the source of what they thought of as magic. She is considered the earthly representative of this personification of force - The Great Mother or Source of all that exists.

With fertility and preservation highly aspected and womankind the link with the Unseen, we merge the factor of imitative acts performed within a prescribed boundary in order that they become reality. This amalgam is the phenomenon of 'ritual' which is an important facet of most religions. And a form of religion this must have been, for any act performed with intent is ritual and to have intent one must have unshaken belief and faith!

Let us not be misled, however, and pause here in an atmosphere of palaeolithic women's liberation, paying little heed to the male of the species and the physical hazards with which he was faced daily in the course of the hunt and in the protection of the weaker members, children and women of the tribe. If primitive religious concepts as we suggest were born of a natural process of inspiration, then, as in the many departments of Nature itself, there must have been some considerable measure of equilibration. What, therefore, of the male counterpart of the Unseen - the masculine or dynamic polarity of this permeation of cosmic power or force?

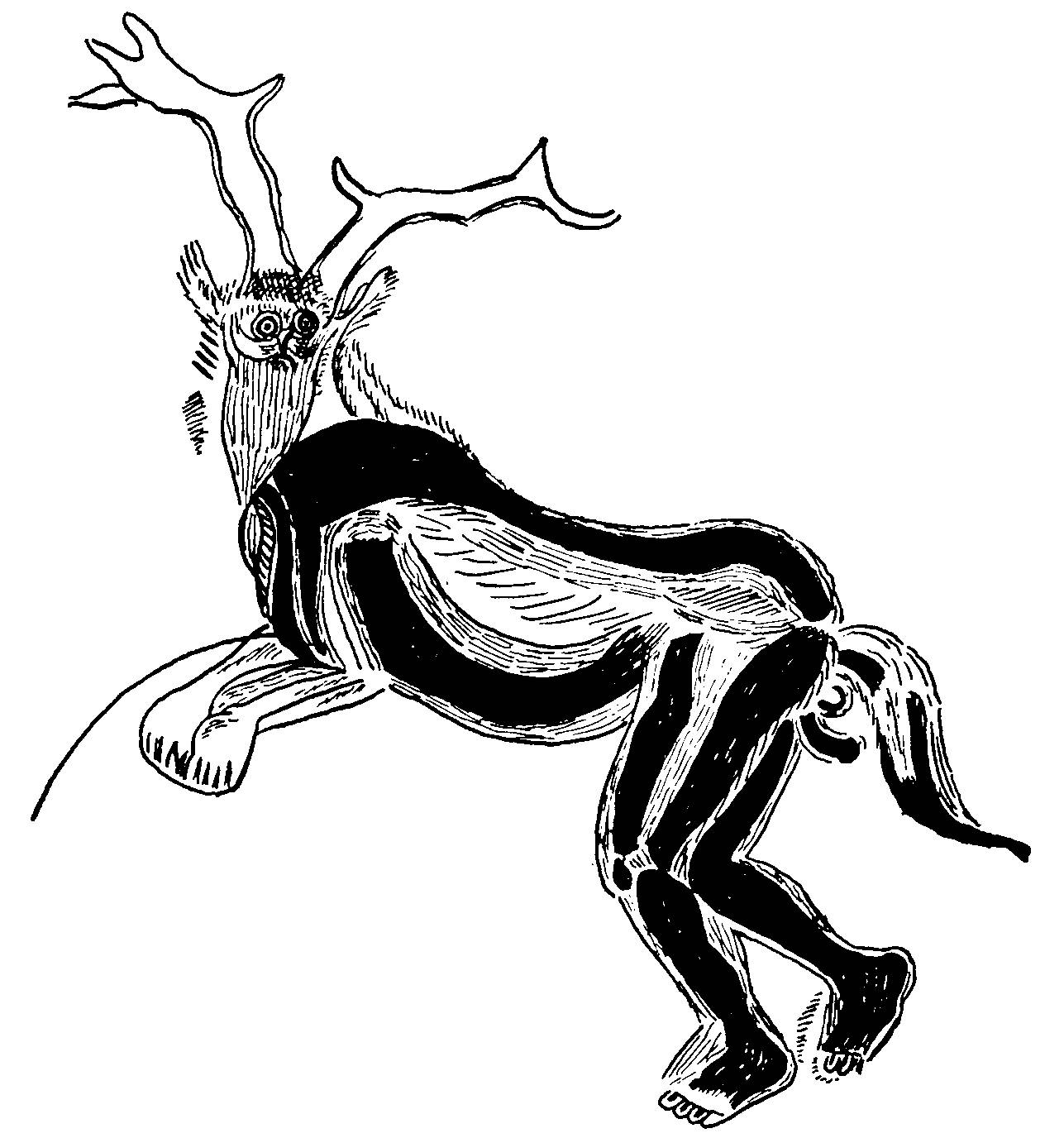

In 1914 on July 20th, Henri Bégouen and his three sons discovered what was later to become the best known of the palaeolithic decorated caves - the 'Cavern des Trois Frères' at Ariège, so named in recognition of the three brothers chance find. Due to the outbreak of the First World War it was to remain unexplored until 1918.

The outline of the

beasts which adorned the walls in this instance was, unlike most others,

engraved upon the rock and not painted. The predominant art work

which was in paint and in a striking black, which was uncommon for that

period, was a two and a half feet figure some three yards above floor level.

The figure was male in form and appeared as a man dressed in animal skins

and adorned with stag's antlers. What is certainly the case is that

the face is bearded, the legs and extremities are humanoid and the general

movement of the figure is decidedly more anthropoid than therionic.

It has been suggested by a few writers on early man and his hunting practices that, prior to the advent of weapons, the strongest and fleetest man of a tribe would wear animal skins to infiltrate the herd and deliberately stampede the beasts, he himself leading them to the edge of a chasm to cause the first few to plunge to their death. Certainly the agility, cunning and courage of such a man would undoubtedly gain the admiration of the entire tribe and would elevate the hunter to the level of chieftain, the tales and myths surrounding his exploits eventually transforming him into a legendary folk hero. And, as we are well aware, folk heroes have the habit of becoming deified to some extent or at least glorified after a number of generations have passed.

In addition to this theory, I have always felt that the stag was symbolic of the concept of 'power'. Whereas modern man may associate the idea of power with the imagery of contemporary air power, aerial weaponry or the latest technological refinements in competitive engines, the picture evoked in the primitive could certainly have been that of an adult stag in full flight. Whatever reason is valid, what is of paramount interest is this graphic representation which underwrites their ability to visualise a natural power or force which was part of their existence - and not simply as a rudimentary totemic animal but raised to the anthropological level of imagery.

Another example of

this type of art is to be seen at Cogul in Spain where the male is surrounded

by dancing women, one of whom carries a knife which again may denote an

imitative act of slaughter. Whatever the motivation in contemplating

this dynamic, positive, energising force, the early mind adapted it and

the Horned God, The Lord of The Hunt was born. From then on, horns

were regarded as a symbol of strength and Divine power as the "horns of

the altar" in Hebrew Scriptures (which became transmuted into 'rays' from

haloed heads) will testify.

Archaeological Evidence (in Britain)

In Britain a few examples of this early art have indeed been discovered, the most publicised being unearthed from below six inches of stalagmite in the Pin-Hole Cave at the Cresswell Crags on the border of Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire. The example is again of a dancing man, ithyphallic, and adorned with an animal mask - the work being engraved upon a bone. Remains found in Wookey Hole in the West Country again include, among ritual objects, horns and a primitive form of scrying crystal. Deep within the caves of Eastry in Kent was a primitive form of shrine where among the various ornaments were the proverbial set of stag's antlers.

Cave shrines in Britain, however, appear to have been the exception as primitive loci for sacred ritual. More emphasis seems to have been on standing stones - either solitary or in circle formation, fashioned in the image of a deity or in their original crude form. Apart from examples at Stonehenge, Avebury and the Outer Hebrides (this latter site housing the Callanish Stones), the Hoar Stone in Pendle Forest, the Bambury Stone on Bredon Hill, the Meigle Stones in Perthshire, the Thrushel in Lewis and the Rodel Circle off the shore of Harris and innumerable specimens in the rural environs of nearly every town and village of these islands are more than ample evidence of the religious observations of our ancestors.

Although as yet we are not concerned with the historical aspects in their written form, it may be interesting to note that early royal edicts forbade "pagan rites at the stones", these appearing as late as the 11th century in the reign if King Canute.

There are instances, too, of the reputed efficacy of these loci being handed down in folklore and being now transformed into mere superstition. What immediately comes to mind is the Men-an-Tol at Penzance, a huge holed stone (the feminine principle again) between two uprights. The hole here is sufficiently large to accommodate the passage of a human and is still used by Cornish people who pass a child through in an attempt to alleviate minor ailments. Most folk customs such as the Abbots Bromley Horn Dance, the Derbyshire Well-Dressings and even the visitation to the Cerne Giant to make productive a childless marriage seem to have their roots in long past religious ideology and observance.

Before departing from the phenomenon of the horned male deity, it may be fitting to recall instances of the portrayal of this particular god-form in Britain, similar to that on the Corinium relief in the Coltswold region:- Meigle in Perthshire, numerous sites in Gloucestershire & Wiltshire, Bath, Aldborough church, Lincoln and from Llyn Tegid in North Wales to Lanchester in County Durham - in fact, throughout mainland Britain.

Whether in the form of a simple stone or as an altar slab, the figure (or often simply the head) is always horned. On occasions the horns are those of a bull but most carvings, such as the altar found at Cramond, Midlothian and a cult-figure at Blackness Castle in West Lothian, show a bearded human head in relief with stag antler adornment. From time to time a decorative device in the nature of a torc is around the neck.

So much, then, for the prima facie evidence of religious loci but what of the evidence of actual observance and ritual practice - no matter how rudimentary?

As we have seen, the early British favoured the shrine rather than the sacred cave and it is to these shrines we should look for the evidence we seek - not to the later Romano-Keltic temples such as Stoney Stratford or Sheepen, Colchester. This, then, is forthcoming at West Coker, Somerset; Glenlyon, Perthshire; Scargill Moor, Yorkshire and Willingham Fen, to give but a handful. As this is not an exposition in archaeology, an in-depth science in its own right, these must suffice and those desiring further examples may make further study of this aspect, preferably with field work during the summer season - and usually at no great distance from home. At the above sites, ritual objects in bronze, figurines, masks and votive deposits have been located. Again the horned heads are much in evidence and figures of birds (often the raven), altars and, at Cavenham Heath, a head-dress and crown all point to religious practice in an overt fashion.

There does seem to have been a greater preoccupation with the water element in the choice of loci, as fragments of folklore confirm, and as deities were of sufficient importance to many springs, wells and rivers, they were the original thought behind the naming of such loci (as in the case of the rivers Clyde and Tay in Scotland) and to portions of parochial terrain. The river Clyde was named after the Gaelic Goddess Cleota while the deity of the river Tay was the Goddess Tatha. The latter in itself is interesting as the Gaels were the Tuatha de Dannan - children of (the Goddess) Danu. In their sweep eastward from Ireland, these early Gaelic settlers had by now created a goddess from the corrupted term for 'children'. The Sidlaw Hills which are north of the Tay owe their name to the Gaelic Sidh meaning 'fairies' and law meaning 'hill'.

Now these centres of observance have yielded up much in the way of evidence and not always of an artistic nature. One of the earliest well-shafts dates from the bronze age - some 2 miles from Stonehenge and in depth 110 feet. At Swanwick in Hampshire there is a shaft of 24 feet depth and from this was retrieved 20 clay loom weights, dating from c. 1200 to 1000 BC, which retained traces of flesh and blood. The 116 feet shaft at Dunstable was found to be full of offerings - coins, pottery, human bones and animal bones. The Biddenham Well was discovered by workmen in a gravel pit about 300 yards from the River Ouse and the 37 feet deep shaft in this case contained a human skeleton, the bones of animals and a damaged altar slab.

Not all are of modern discovery and many are exposed simply by accident. A well-shaft similar to the Biddenham was found at Sawbridge in Warwickshire as far back as 1689. Neither should we be perturbed by the few unsavoury remains, as these seem to have been the exception rather than the rule, and, as tribes evolve throughout centuries and millennia, these isolated examples and their morality are no more to be judged by modern minds than are nuclear holocaust, indiscriminate terrorism and genocide by the primitive mind.

We have simply endeavoured

to establish the archaeological evidence of the existence of religious

concepts and observance by our ancestors and their neighbouring kin in

time.