Dashed Hopes

After Orbital Test Flight, Pioneer Astronaut Presumed Dead

by Jeannette Richmond

March 14, 1999

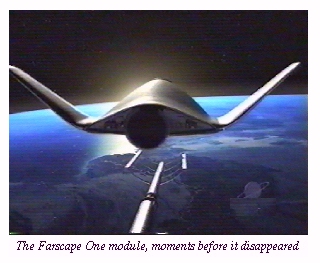

The mission seemed foolproof. All the signals were go. There was every indication that the Farscape One module would begin a new era of high-speed space flight and usher in the next generation of engineering feats at the International Aeronautics and Space Administration. The pilot and co-designer sat at the controls, and waited for final permission to begin.

But instead of crossing new boundaries in the still-nascent science of low-gravity propulsion, IASA Mission Specialist John Robert Crichton, Jr., disappeared almost literally in a cloud of smoke, taking his experimental spacecraft with him. As his colleagues, fellow engineers, and the crew of the IASA Shuttle Clarion looked on in horror, the Farscape One module moved into place on March 10, at 2:30 pm CST, accelerated into a patch of anomalous radiation, and vanished without a trace.

"At this time, we must acknowledge the realities of survival in space, and officially list Commander Crichton as presumed dead," said Tyrone Marchioni, ground commander of the mission. (Crichton, a civilian, is accorded an IASA title.) "The likelihood of his surviving the incident is extremely low, and we have been unable to locate the module itself even if we were to attempt to mount a rescue mission." Marchioni related this news, with few details, at a press conference in Houston today. He took very few questions, but space travel experts who have looked at the plans for the Farscape One agree that by now, Crichton would have run out of oxygen.

The shuttle Clarion is scheduled to land at Edwards Air Force Base in the early hours of March 16. The crew, reduced to 6, will be debriefed once they reach firm earth. But already, eyewitness accounts are trickling into the newsmedia. "It looked like a huge ball of static," said a Houston mission technician, who preferred not to give his name. "The module flew into it and was gone. Just like the Bermuda Triangle."

What Went Wrong?

As reported in these pages ("Childhood Friends Out to Prove a Theory," Feb. 26,1999), the Farscape One test flight was intended to try a new method for a spacecraft's acceleration, using a planet's own atmosphere. Mission failure, experts suggest, should have been the module simply going nowhere fast.

"There was nothing obviously dangerous in the mission, on paper," said Jeffrey Jourdan, professor emeritus of physics at the California Institution for Technology and a former IASA mission commander. "Everything in space is a hazard, but barring massive technical failure, the craft and the theorem seemed sound." The Kern-Crichton Theorem, known commonly as the 'slingshot' theorem, is named for the missing Crichton and his childhood friend and fellow physicist Darius "DK" Kern. But it may be the putting of theory into practice that spelled doom for the young astronaut.

The maneuver Farscape One had planned involved flying at an angle into the outer edge of Earth's atmosphere. Anything that enters the atmosphere at high speed runs the risk of friction-induced heat, and possible fire: space shuttles are equipped with special heat shields for re-entry. Farscape One, intending to use just that friction to convert heat into speed, was covered entirely with a skin of polymer heat-shield material. But even a tiny flaw in the outer skin could have caused a fatal disaster.

And what of that 'big ball of static'? Some radio and satellite

communications systems reported a loss of service during the same

time of the Farscape One's disappearance. Telescopes around

the world are beginning to release images of the phenomenon, which

may be related to the recent spate of solar flares. Solar flares

are known to interfere with telecommunications signals, causing static

on televisions and spotty cellular reception. But can the radiation

from a solar flare kill? Or was it some other kind of electrical

disturbance? (See sidebar, What

the Heck Was That?)

And what of that 'big ball of static'? Some radio and satellite

communications systems reported a loss of service during the same

time of the Farscape One's disappearance. Telescopes around

the world are beginning to release images of the phenomenon, which

may be related to the recent spate of solar flares. Solar flares

are known to interfere with telecommunications signals, causing static

on televisions and spotty cellular reception. But can the radiation

from a solar flare kill? Or was it some other kind of electrical

disturbance? (See sidebar, What

the Heck Was That?)

Solar flares or no, says Jourdan, there should be some debris if the space craft was destroyed. "Paint chips from the Apollo missions are still orbiting our planet," he pointed out. "Surely some remains of the module should be visible from space." Even if the Farscape One burned up in a disastrous re-entry accident, he said, there should have been a discernible visual 'footprint', like a shooting star, seen by observing telescopes.

"But no-one has come forward to say he has seen such things," added Prof. Jourdan, shaking his head sadly. Referring to Crichton, he confessed, "My fear is that he lost control of the module and was stranded in a trajectory headed away from Earth." In that event, the astronaut would surely die of cold and asphyxiation within a few days.

A Public Relations Disaster

"We're reaching for the stars," says the man, blue-eyed and tall, smiling into the camera. John Crichton filmed several short commercials for the IASA shuttle program not long before his final mission. The publicity campaign, an attempt to revive interest among young people in the world's space program, will be pulled in light of its star's death. Natalija Zimm, IASA press agent, admitted, "It's just too awful to show these ads now." Awful, too, for the IASA publicity department, which had pinned its hopes on the handsome astronaut to change the rather staid image of international space exploration. (See sidebar for a Profile of John Crichton.)

Zimm explained, "We want the world to see that you can work for the government and still be cool. John Crichton was an egghead of the highest order, an astrophysicist, but he was also a great guy and full of an infectious enthusiasm. The loss of him is astounding, and the loss of his influence on the future of the IASA is a crippling blow."

Even more painful was the admission, by Mission Commander Marchioni, that along with Kern, Crichton's father, Captain John Crichton Sr., was observing at Cape Canaveral when the ship disappeared. A Navy test pilot and later an astronaut himself, Captain Crichton had watched his son successfully complete two previous shuttle missions, in 1995 and 1997.

"He was ordered to abort the test flight," said Marchioni, referring to the younger Crichton, "but we cannot say at this time whether he could hear the order. We will be reviewing recordings in the coming weeks to determine where communication failed and how we can repair it." Marchioni would not comment on what, if anything, the remaining crew of the shuttle Clarion had witnessed. "I want to get them on the ground, back to safety, before I put any more demands on them," he said.

Observers compared this most recent accident with other disasters in the history of the world's various space programs. "Clearly, there have been worse mistakes made," said historian Heather Azikiwe. "The Apollo 1 fire, the shuttle Challenger, and several of the old Soviet Union's errors resulted in multiple deaths in a single incident." Those situations, however, have all been tied to mechanical failures in the technology itself. "The disturbing aspect of the Farscape One debacle is the absence of evidence from which we can extrapolate where the system broke down."

During his generally terse statement to the press, Marchioni had one moment of eerie poetry: "We don't know where the module is. It's as if the hand of God reached down and took it away."

What Now?

How will IASA and the Farscape Project pick up the pieces?

Azikiwe recalls the long wait, after the Challenger disaster,

before manned ships were allowed back into orbit. "It scared everyone

in the space-faring community," she said. "It nearly crippled the

American space program for years." It was only the reorganization of

space exploration into an international endeavor that re-opened

the door to humans on the space shuttle.

Marchioni, however, disputed comparisons to Challenger or the Apollo 1 fire. "I've still got a crew of astronauts up there," he said, bristling at a reporter's question. "There are six people still alive who are coming home, and who will go back up into orbit again." When asked to comment on the status of the Farscape Project itself, or about the unorthodox move of having an astronaut double as a test pilot, Marchioni would only say, "We made some decisions, and we're going to have to review everything we've done. Frankly, we'll cross that bridge when we come to it."

As for Kern, whose entire career has been invested in the Farscape Project, he will be heading back to the drawing board. He appeared at the press conference haggard and exhausted, mourning his friend, co-worker and the co-author of his groundbreaking theorem. He said he would be working around the clock to find any flaws in his plans and build another Farscape module.

"It's the least I can do, in John's memory, to get back on the horse and find out what went wrong," he said this afternoon, with visible emotion. He went on to explain that Crichton had had 'a feeling' the morning of March 10, but had gone ahead with the experiment. "This is science," shrugged Kern. "Until this week, I would have said that you don't scrap a mission on a feeling."

Jeannette Richmond is a reporter for the fictional magazine Newstime. Read more about this fictional article.