Liszt's Study-Bedroom in Budapest with prayer stool and icon

In a cultural atmosphere marred by many religious dichotomies, where

theology and worship seem to be rarely connected, there are several compelling

reasons to consider the life and music of Franz Liszt. Today,

where the priorities of consumerism and entertainment often substitute

for liturgical adoration, Liszt's understanding of music as an "aural sacrament"

can breathe spiritual life into the liturgical and theological offerings

of the Church. For Liszt's theology of the arts offers today no less

that a return to a sacralized worldview where art and especially music

serve as a type of sacrament - a physical manifestation of the grace of

God.

This understanding at its best will condemn a rationalistic

approach to reality that leaves no room for the numinous. Rather,

Liszt's Catholic imagination calls us back to Eden where the primal purpose

of creation as a means of communion with God was first actualized.

Powerfully rejecting a gnosticism that inherently denied the ability of

the physical human being to be joined to God, Liszt held that music

functions as a type of theophany, a divine manifestation. He writes

"Art is heaven on earth, to which one never appeals in vain when faced

with the oppression of this world." It is this incarnational

understanding of art that links Liszt to the great ideas of both the Christian

east and west. The great Russian monastic Theophan the Recluse

once described prayer as the descent of heaven into the soul.

We see with Liszt that music and art function as a divine descent where

the depths of our soul are filled with the grace of God.

The following examination of Liszt will focus on Liszt's personal

understanding of Catholic theology and its influence on what would later

become what I have called his theology of music. After an initial

treatment of Liszt's personal faith including his important spiritual mentors,

Liszt's own writings will be explored revealing an understanding of art

that has fascinating intersections with the Eastern Orthodox theology of

the icon. Liszt actively embraced those theological concepts defined

during the first Christian millennium of the undivided Church when both

the Latin West and the Greek East spoke a theological language that had

much in common. Important themes included the embrace of mystery

and an understanding of the limits of the human intellect.

Life was also seen as essentially sacramental - God does in fact communicate

his grace to us through creation. And certainly related to

this sacramental world view is the concept of art, specifically the icon,

communicating a theology of presence. Articulated most powerfully

by eastern theologians during the iconoclastic controversies of the seventh

and eighth centuries, the icon was seen as an artistic vehicle both protecting

the physical reality of Christ's incarnation and communicating that

incarnation to the people of God. And just as the icon invites

an encounter with the sacred, so Liszt believed music facilitated a direct

experience of God. Finally with a clear understanding of this sacramental

function of music, I will examine Liszt's greatest composition, the Sonata

in B Minor, as the example par excellence of music functioning as a sacramental

bridge between heaven and earth.

Liszt's Theological formation

After his initial encounter with the twenty-two year old Franz

Liszt, the Abbe Felicite de Lamennais remarked "I can't remember ever having

met a more sincere enthusiasm; this enthusiasm he has lately concentrated

entirely on our religious and political doctrines; they have brought him

to a real and practical faith." One of the major impulses for

writing this essay is to dispel the still popular notion that Liszt was

at his core a superficial showman and womanizer seeking the solace of the

Church only in the waning years of his old age. Yet it is clear from

both Liszt's letters and the comments of his closest friends that Liszt's

devotion to Christianity was genuine and that he was drawn to the church

from a very young age. Liszt’s father Adam himself entered

the priesthood only to be dismissed after less than two years “by reason

of his inconsistent and changeable character.” At sixteen,

Liszt begged his father for permission to attend the Paris seminary and

devote himself completely to the church. But with his own vocational

failure undoubtedly fresh in his memory and a parental understanding of

his son's unique musical gift, Adam was convinced that Liszt's true vocation

was music. Yet we have expressed in Adam the important truth for

Liszt that religion and art are intimately connected: "The

path of a true artist does not lead away from religion- it is possible

to have on path for both. Love God, be good and upright, so that

you will reach ever higher in your art. "

A second influence on Liszt's theological development was his

intense interest in Christian literature including The Lives of the Saints

and Thomas a Kempis' classic The Imitation of Christ. Surrounding

himself with the mystical atmosphere of Christian martyrs and monastics,

Liszt developed an ascetic approach to his inner life. He spent hours

in prayer always examining his conscience. When Liszt would

take holy orders at the age of fifty three, he could honestly state that

the church was his vocation from the start. He writes in his will of 1860:

This is my Will. It is made on this 14th day of September 1860 when the church celebrates the Exaltation of the Holy Cross. The name of this festival also expresses the burning and mysterious feeling which has marked my whole life as with a sacred stigma. Yes, the crucified Jesus, the ardent yearning for the Cross and the exaltation of the Holy Cross, this way my true vocation. (emphasis mine)

The passionate accounts of martyrdom and the profound sacrifice of the

monastic no doubt influenced Liszt's social conscience culminating

in his view of the social responsibility of the artist serving both

the people and God.

A third influence on Liszt was the moral intellectual movement

in vogue in nineteenth-century Paris known as Saint- Simonism.

The Saint-Simonists, with whom the important Romantics figures Heinrich

Heine, George Sand and Hector Berlioz were all associated, attempted to

unite the teaching of Christ with socialism. They were a revolutionary

group of artists and intellectuals radical enough to take the Sermon on

the Mount seriously and attempt to implement these teachings at the societal

level. The group certainly had a major impact in the development

of Liszt’s social conscience and the Romantic idea of the artist as God’s

creative manifestation whose purpose was to edify the people. Liszt

himself wrote about his attachment to the revolutionary concepts of Saint-Simonism:

“I will confess that I think more highly of the utility of certain ideas formerly preached by the disciples of Saint Simon than it is expedient to say...’the moral, intellectual and physical amelioration of the poorest and most numerous class, science associated with industry, art joined to worship, and the famous assessment ‘each according to his capacity’ do not seem to me fantasies empty of sense.” (emphasis mine)

Liszt biographer Alan Walker comments on the intense attractiveness of Saint Simonism to so many of the rising young Romantics:

"Had not Emile Barrault, the movement's leading aesthetician and finest public orator, already placed art at the center of life and elevated the artist to a new priesthood? The artist walked in heaven; he was the chosen vessel through which God transmitted divine fire."

Although Liszt was hesitant to claim full membership in this revolutionary

group, it is clear that the basic ideas of Saint-Simonism were critical

in his understanding of the divine role of music and its ability to transform

and improve society.

One final influence to consider in the development of Liszt's

emerging theology of the arts was the Abbé Félicité

de Lamennais. Lamennais’ spiritual impact on Liszt was monumental.

He was to Liszt a spiritual and artistic mentor, with whom Liszt spent

the entire summer of 1834 at Lamennais’ country manor, La Chenaie.

Liszt himself writes about his mentor:

“The abbe, our good father, takes his straw hat, completely worn out and torn in various places, and says...”Let’s go, children, let’s go for a walk,” whereupon we are launched into space for hours at a time. Truly, he is a marvelous man, prodigious, absolutely extraordinary. So much genius, and so much heart. Elevation, devotion, passionate ardor, a sharp mind, profound judgment, the simplicity of a child... I have yet to hear him say: I. Always Christ, always sacrifice for others, and the voluntary acceptance of opprobrium, of scorn, of misery and death.”

Lamennais' magnum opus Esquisse d'une Philosophie appeared in 1840 in three volumes with the third volume devoted largely to art. Liszt would later echo Lamennais' understanding of the sanctifying power of music:

Music, a sister of poetry, effects the union of the arts, which

appeal directly to the senses, with those which belong to the spirit;

there object is... to second the efforts of humanity, that it may fulfill

its destiny of raising them from the earth, and therefore by inciting to

a continual upward striving.

Like the disciples of Saint-Simon, Lamennais viewed art as a manifestation

of God. Walker writes: “Art for Lamennais was God made

manifest; it ennobled the human race; insofar as the artist was a bearer

of the beautiful, he was like a priest ministering to his congregation.”

And just as the priest bears the tremendous pastoral and sacramental

responsibility for the spiritual well-being of his flock, so the artist

has a similar obligation. Génie oblige! became Liszt's artistic

motto. He went as far as to condemn Paganini whom he viewed as a

negative modal for the artist:

“May the artist of the future gladly and readily decline to play

the conceited and egotistical role which we hope has had in Paganini its

last brilliant representative. May he set his goal within, and not

outside himself, and be the means of virtuosity and not its end.

May he constantly keep in mind that, though the saying is Noblesse oblige!,

in a far higher degree than nobility - Génie oblige!"

Liszt would later write of the immense social responsibility of the

artist: Music must recognize God and the people as its living source; must

hasten from one to the other, to ennoble, to comfort, to purify man, to

bless and praise God.”

Liszt's theology of the arts

The embrace of mystery

With the influences of his father, St. Simonism, and Lamennais,

Liszt's deeply personal faith combined with an understanding of the role

of art in society reflects a Catholic worldview that embraces the traditional

Christian concepts of mystery, sacramentality, and a theology of presence.

Unlike the rather naive empiricism that characterizes a world-view dominated

by scientific method, Liszt understood the limits of human intellect and

embraced the mysterious and the numinous. Orthodox bishop Kallistos

Ware writes of the true nature of Christianity: “We see that it is

not the task of Christianity to provide easy answers to every question

, but to make us progressively aware of a mystery. God is not so

much the object of our knowledge as the cause of our wonder.”

And with this understanding of the limits of reason, Liszt writes :

"Only in music does feeling, in manifesting itself, dispense with the help

of reason and its means of expression, so inadequate in comparison with

its intuition..."

Far from accepting the Enlightenment dogma of 'saved by reason,'

Liszt's sacramental awareness revealed that true knowledge of God is beyond

human intellect. The apophatic theology of the East or the "theology

of negation" as articulated by Maximus the Confessor and Pseudo-Dionysius

similarly embraces the numinous and the limits of human reason. Understanding

the existence of God to be beyond "being," these theologians understood

true theological knowledge to be limited because of God's transcendence.

One cannot know God in an intellectual sense because He is in fact beyond

intellect. Only through God's grace and energy, His sacramental manifestations,

can God be known in any meaningful way.

Yet Liszt's mysticism is not escapist or void of a social imperative.

Just as Christian mystics and monastics would retreat from society to later

return, Liszt saw his 'musical mysticism' as a means of intensifying life

on earth:

"Is not music the mysterious language of a faraway spirit world

whose wondrous accents, echoing within us, awaken us to a higher, more

intensive life?”

Incarnational and Sacramental Reality

The foundation of Liszt's embrace of Christian mystery is his

affirmation of sacramental reality within the life of the church.

In fact the two concepts have much in common. In the Greek churches

of the Orthodox world, the ancient Greek term "mysterion" was used

to describe those particular manifestations of God's grace given to the

church such as baptism, holy communion, marriage, i.e. the sacraments.

Through the Holy Eucharist, the communicant becomes a partaker of the 'divine,

immortal, and life -giving mysteries. Liszt's deep awareness

of the mysterious and sacramental element of Christianity had deep impact

on his view of art. Yet it is not the disembodied mystery of

eastern oriental thought, but rather the uniquely incarnational mystery

of the Christian gospel that inspired Liszt. Liszt would whole-heartedly

affirm Russian theologian Boris Bobrinsky's understanding of the human

person: “Mankind is a sacramental being by nature and needs the instrumentality

of both sacraments and symbols to attain communion with the Invisible.”

And Liszt's understanding of the physical and sacramental

element in Christianity simply reflects his understanding of a theology

powerfully articulated fifteen hundred years earlier by St. Athanasius

of Alexandria. Defending the physical reality of the incarnation

of Christ against both the heresy of Arianism that denied Christ's divinity

and that of docetism which denied his humanity, Athanasius' incarnational

theology embraced the physical world as a means to communion with

God. Bishop Kallistos writes, “It is the human vocation to

manifest the spiritual in and through the material. Christians in

this sense are the only true materialists.”

And it was Liszt's orthodox and catholic understanding of the

interconnectedness of the physical and spiritual, his powerful rejection

of a gnosticism that would denigrate the physical, that lead to his severe

criticism of Protestantism:

"How in the end did [the reformers] not perceive that to try to spiritualize religion to the point where is subsists devoid of all external manifestation is tantamount to claiming a reform of the work of God, the great and sublime artist who, in creating the universe and mankind, revealed himself as the omnipotent, eternal and infinite poet, architect, musician, and sculptor."

For Liszt, the gospel could never be reduced to 'doctrine' or mere mental

assent to a particular world view. Christianity was nothing less

than the visceral, physical encounter of God with his creatures thought

the church that Christ founded to be his ongoing incarnation to the world.

Another critical element in Liszt's sacramental view of music

was its ability to heal the soul and to inspire the faithful in moral progress.

Here again, this quality of music has remarkable similarity in the

mind of Liszt to the eucharistic theology of the church. Liszt's

spiritual guide Thomis a Kempis writes in the Imitation of Christ:

“Like a balm for your soul, Holy Communion will help you to overcome your

weaknesses and bad habits, so that you may be stronger and more watchful

against all the temptations and deceits of the devil.” Liszt

would have no trouble transferring this same medicinal function to music.

Alan Walker comments on Liszt's belief in the healing power of music:

“Music, for Liszt, was the voice of God. He often behaved as if music

possessed healing properties. Because of its divine origin, he seemed

to say, mere exposure to it was a spiritual balm.”

Music as the Sacred Bridge

One final element that completes Liszt's theology of music is

the important theological quality of mediation. Music in Liszt's

mind functioned no less than a sacred bridge, mediating heaven and earth.

“Art is heaven on earth, to which one never appeals is vain when faced

with the oppressions of this world.” And this understanding

of art as the descent of heaven to earth again brings to mind the theology

of art so powerfully expressed in the Orthodox tradition of iconography.

In a lecture at Princeton Theological Seminary, Bishop Kallistos assigned

the following role to the icon: "The icon serves a mediatory function

between God and man, and mystically reveals a meeting place between heaven

and earth" Walker again comments on Liszt's view

of music as the intermediary of the human and divine: “More than

once he used the metaphor of the priest or acolyte. He called the

artist “the Bearer of the Beautiful,’ an intermediary between God and man.”

And late in his life, Liszt wrote in the preface to his musical setting

of The Seven Sacraments: “I intended to give expression to

the feeling by which the Christian takes part in the mercy that lifts him

out of earthly life and makes him aspire to the divine atmosphere of heaven”

This tremendously powerful and physical spirituality of Franz

Liszt is also manifest in his personal prayer life. At the

Liszt Museum at the Academy of Music in Budapest, Liszt's study bedroom

is preserved as it was during his final years. The bedroom radiates

a spiritual presence made most powerful by Liszt's own icon of Christ in

front of which he prayed every night. The icon is that of the face

of Christ commonly know as "Made without Hands." The genesis of the

icon is the story of King Abgar of Edessa who being stricken with

leprosy sent an ambassador to Christ for healing. Being detained

by the multitudes, Christ simply wiped his face on a cloth and gave it

to the envoy. Upon his return to King Abgar, the cloth radiated with

the image of the face of the Savior, and the King was healed of his leprosy.

A similar legend exists in the West as the Station VI of the Via Crucis

devotional with St. Veronica (literally "true icon") wiping the face of

Christ with his image miraculously transposed to the cloth. These

stories communicate most powerfully the Orthodox understanding of the icon

as a personal manifestation of divine presence. And just as Liszt

believed music served as this most sacred bridge between God and man, he

would no doubt affirm Orthodox theologian Paul Evdokimov's statement about

the icon: "The icon is a sacrament for the Christian East; more precisely,

it is a vehicle of a personal presence."

Liszt's Study-Bedroom in Budapest with prayer stool and

icon

The Sonata in B Minor as an "aural" icon

With a clear understanding of the above theological concepts and their

connection to Liszt's view of music, we can now consider how Liszt's theology

of music was in fact applied. I have selected Liszt's monumental

Sonata in B Minor as the artistic vehicle through which Liszt's sacramental

view of music can be most clearly seen. Composed in 1853, Liszt's

B Minor Sonata has long been a tour de force among pianists and remains

an indispensable part of the pianist's repertoire. The form

of this giant thirty minute work is both unique and ambiguous. Rather

than constructing a typical multi-movement sonata typical of the sonatas

composed in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, Liszt creates

a gigantic one movement form that contains all the basic elements of the

multi- movement sonata cycle. Yet there is little that is neat

and contained or totally satisfying about any particular analysis of this

great work. This is one reason that musicologists are still inspired

to add their "new" analyses to an ever-growing list of noble attempts.

Yet no one issue related to the Sonata ignites greater passion than the

idea that the 'sonata', a term used to denote "absolute" music with no

external program, might actually contain extra musical references.

It is this writer's contention that the sonata is in fact a gloriously

vague hybrid of both the "absolute" sonata and the epic tone poem, a programmatic

form for which Liszt is given credit for inventing. Given Liszt's

remarkably articulate views on the sacramental nature and social purpose

of music, it would seem most natural to search for a programmatic meaning

to such a monumental composition. Yet it must be acknowledged

that while Liszt did give very evocative titles to many of his works, he

did restrict himself simply to the rather austere and ascetic term "Sonata."

However, an understanding of Liszt's life, theology, and his view of the

sacramentality of art articulated above should at least convince the hardened

skeptic to consider and seek out whether extra musical references might

exist in the Sonata. Given Liszt's articulate 'theology of music'

and various internal musical references to be discussed below, I believe

a monumental work like the B minor Sonata can in fact be understood as

a type of aural icon, revealing the mysterious spirit world in a way that

transcends word and thought. In fact, what St. John of Damascus says about

icons might describe Liszt's intention for the sonata: “[it] is a song

of triumph, and a revelation, and an enduring monument to the victory of

the saints and the disgrace of the demons.”

The Cross Motive

Liszt himself identifies what he himself calls the "theme of

the symbol of the Cross" at the end of the full score to his oratorio The

Legend of St. Elizabeth composed in 1862. He quotes two Gregorian

melodies that begin with the same three notes: the Magnificat and

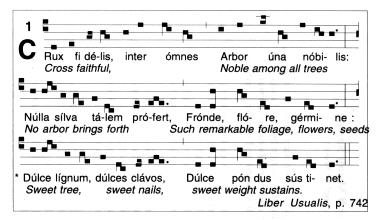

Crux fidelis.

[Cross motive example here]

He then identifies several works that use this cross motive and said that "among others" was Hunnenschlacht (1857), the Magnificat from the Dante Symphony (1855-6), the Gloria from his Missa Solemnis (rev. 1857-58), and the March of the Crusaders from Elizabeth (1862). Many scholars believe that the "among others" must refer to the Sonata, the only other work Liszt had written by 1862 that utilizes the cross motive. The cross motive is also used prominently in later works like Via Crucis written in 1878. Liszt writes about Hunnenschlacht:

“In the middle of the picture appears the Cross and its mystic light: on this my Symphonic Poem is founded. The chorale ‘Crux Fidelis’ which is gradually developed, illustrates the idea of the final victory of Christianity in its effectual love to God and man.”

There can be absolutely no doubt than when Liszt used these intervals, it was in the context of a programmatic work on a Christian subject. Wagner certainly understood this when he borrowed Liszt’s cross motive in his final opera Parsifal. Compare the Theme of the Holy Grail to the sonata’s Cross theme:

[Liszt Cross theme from the Sonata and Wagner Theme of the Holy Grail from Parsifal]

One of Liszt's pupils recorded his reaction to this alleged plagiarism:

“Wagner himself said, ‘Now you can see how I have stolen from you!’

However, they are old Catholic intervals, and so even I did not invent

them myself.”

Contrary to those arguing against a program for the Sonata, whenever

Liszt used the specific intervals that make up the cross motive, it is

always in the context of a large-scale programmatic work based on a Christian

subject. And the cross motive and its characteristic harmonization

are unmistakably in the Sonata.

And if one accepts this basic premise, understanding the sonata

as Liszt's aural icon creates further connections with Liszt's theology

of music. Just as Liszt's icon of the face of Christ functioned as

a vehicle of a personal presence to Liszt as he prayed, in a similar way,

the numerous appearances of the cross theme in the sonata can be seen to

represent a type of musical theophany, a musical manifestation of the presence

of Christ. And amidst the other imagery of the diabolical

for which Liszt is duly famous, these musical theophanies can create in

the listener a sense of God's divine presence amidst the most chaotic and

demonic of environments. And just as the icon is used most properly

in the liturgy of the church's corporate prayer, so Liszt's appropriation

of Gregorian chant, the Crux fidelis hymn, creates in the informed listener

a psychological connection with liturgical prayer. And it is this

profound sense of juxtaposition between the diabolical and the divine,

of the song of the demons and the song of the church, that gives the listener

a true experience of spiritual reality. Just as the faithful receive

a heavenly glimpse in liturgical adoration, a reconfirmation of their true

citizenship in heaven, so the faithful listener to Liszt's Sonata in B

Minor will gain an understanding of the triumph of the cross, the ultimate

victory of the saints, and the disgrace of the demons.

Regaining Eden

In today's fast paced, disposable culture, Liszt's vision of

music as a sacred bridge, as a sacramental experience of the presence of

God, invigorates and transfigures a musical experience. For those

that desire clarity, neatness, and order, Liszt's music will seem like

a foreign country. But for those seeking the danger of divine

encounter, Liszt's music offers no less than the true aim of Christianity

- to make us progressively aware of a mystery.

Liszt's Sonata in B Minor can undoubtedly be loved and enjoyed

on many levels. And I would never argue that anyone not accepting

a programmatic impulse in the Sonata would enjoy it less. Yet musicology

in the twentieth century has given us great insight into the cultural lives

of composers throughout time. One could certainly enjoy Rachmaninoff's

beautiful Vespers as 'pure' music. Yet an understanding of

the theology of the Russian Orthodox 'All-night vigil' will undoubtedly

open new avenues of appreciation and awareness. And for music

lovers of all types, the depth of enjoyment is intrinsically connected

to a depth of understanding.

Many may react negatively to the above beatification of Franz

Liszt. And it is important to remember that Liszt was indeed

a man of great inner contradictions. While I greatly appreciate his

contribution of music and his development of a theology of art, it is also

clear that Liszt was hardly a saint in the traditional sense.

He was indeed a fallen man. Yet Liszt in his fallen state ranks with the

greatest of saints at least in his personal acknowledgment of his own shortcomings

and in his tireless work for the betterment of society. He wrote

about the particular tempatation of music: "Music is at once the

divine and satanic art that more than all other arts leads us into tempatation."

Yet even amidst the tempatations of the musical world, Liszt did devote

himself unselfishly to the music of others and was genuinely concerned

about the betterment of society.

In the tradition of the poet/priest, a company for whom Liszt

might be awarded honorary membership by a generous and merciful judge,

the musicians's greatest contribution to mankind was his ability to offer

divine hymns to God. The greatest poet and musician of the eastern

Christian world, the fifth-century St. Romanos the Melodos expresses beautifully

the musical and artistic intent of Liszt's music:

O Savior, may my deadened soul arise again with You.

May sorrow not destroy her and may she not ever forget these songs

which sanctify her.

Yes, O Merciful One, do not pass by me spotted though I am with many

sins.

O my Father, Holy and Compassionate, may Your Name be forever

hallowed in my mouth and lips, in my voice and in my song.

Grant grace to me when I proclaim Your hymns, for You have the

power,

You Who offers resurrection to fallen man.

Selected Bibliography

St. Athanasius of Alexandria (298-373). On the Incarnation. St. Vladimir's Seminary Press, Crestwood, NY, 1993. Reprint of English edition published in 1944 with an introduction by C.S. Lewis.

Evdokimov, Paul (1901-1970). The Art of the Icon: a Theology of Beauty. Oakwood Publications, Redondo Beach, CA, 1990. Originally published in French, Paris, 1972.

St. John of Damascus (c.657-c.749). On the Divine Images. English translation by St. Vladimir's Seminary Press, Crestwood, NY, 1980.

Kandinsky, Wassily (1866-1944). Concerning the Spiritual in Art. Dover Publications, 1977. Reprint of first English translation published in 1914.

Lamennais, Felicite Robert de (1782-1854). Esquisse d'une Philosphie. 3 volumes. Paris, E. Renduel, 1840.

Merrick, Paul. Revolution and Religion in the Music of Liszt. Cambridge University Press, London, 1987.

Pelikan, Jaroslav. The Emergence of the Catholic Tradition (100-600),

University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1971.

Pelikan, Jaroslav. The Spirit of Eastern Christendom (600-1700).

University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1974.

Quenot, Michel. The Icon: Window on the Kingdom. St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, Crestwood, NY, 1991. Originally published in French, Paris, 1987.

Schmemann, Alexander (1921-1983). For the Life of the World.

St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, Crestwood, NY, 1973.

Strunk, Oliver. Source Readings in Music History. Norton

& Co. New York, 1950.

Szasz, Tibor. “Liszt’s Symbols for the Divine and Diabolical: Their Revelation of a Program in the B Minor Sonata.” Journal of the American Liszt Society, 15 (1984): 39-95.

Thomas à Kempis (c.1379-1471). The Imitation of Christ. Ave Maria Press, Notre Dame, IN, 1989.

Topping, Eva Catafygiotu. Sacred Song: Studies in Byzantine Hymnography. Light and Life Publishing, Minneapolis, MN, 1997.

Walker, Alan. Franz Liszt: The Weimar Years. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY, 1989.

Walker, Alan. Franz Liszt: The Virtuoso Years (rev. ed).

Cornell University Press, Ithaca NY, 1987.

Walker, Alan. Franz Liszt: The Final Years. Alfred

A. Knopf, New York, 1996.

Ware, Kallistos. The Orthodox Way. St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, Crestwood, NY,1979.

Weiss, Piero and Richard Taruskin. Music in the Western World:

A History in Documents. Schirmer, New York, 1984.