| |||||||

| ||||

The musical estate of J.S. Bach’s second son, Carl Philipp Emanuel, has finally been found after a long search lasting more than two decades. The estate, discovered by scholars this summer in a Ukrainian archive, includes hundreds of unpublished scores by J. S. Bach's sons and forebears and had been previously feared lost or destroyed.

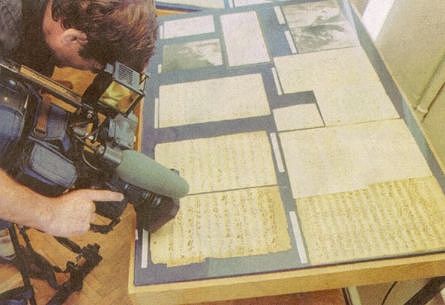

In fact, the valuable collection has been in Ukraine ever since the Red Army took it from Germany as a trophy after World War II. The search began in the ’70s when Dr. Christoph Wolff, a music professor at Harvard University, was tipped off by a librarian in East Berlin that C.P.E. Bach's estate was stashed somewhere in Ukraine. He was then writing the Bach family entry for The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. Wolff enlisted the help of Dr. Patricia Kennedy Grimsted, a specialist in Soviet trophy archives and an associate of the Ukrainian Research Institute at Harvard. But it was only this year that the case began to crack. In researching her forthcoming book about war spoils, Trophies of War and Empire, Dr. Grimsted came across a German translation of a 1957 report by the Soviet Ministry of Culture that mentioned some 5,100 musical manuscripts in a conservatory in Kiev. But when the conservatory officials were questioned about the document, they said they knew nothing about it. At this point, Dr Grimsted’s colleague, Mr. Hennadii Boriak, deputy director of Ukrainian archeogeography and sources studies at the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences, stepped in. He found a librarian who remembered seeing a report about a music collection being moved in 1973 to the Central State Archive-Museum of Literature and Art in Kiev. Archive officials confirmed that they had a collection of some sort, but offered no further information. This spring, when Mr. Boriak got to see the collection, no one knew what it contained. Dr. Wolff asked him after his visit: “Does it contain the Bach family name?” He responded. “Yes, quite a few.” But that was nowhere near the end. In June, Dr. Grimsted and Dr Wolff arrived in Kiev to appraise the collection and met with a string of delays. Their first day there was a holiday. On the second day, the archive was being renovated. On the third day, the archive’s director showed the scholars an inventory of the archive, but not the collection itself. Finally, the director pulled down a box. It contained about six bound manuscripts and bore the stamp of the Berlin Sing-Akademie, the choral society that had inherited C.P.E. Bach’s estate. The scholars knew they had hit paydirt. About a tenth of the collection contained Bach family manuscripts. There were a few scores by J.S. Bach (most of his manuscripts have been in the state library in Berlin since 1854). But the bulk of the find was a collection of unpublished manuscripts by J.S. Bach’s two eldest sons, C.P.E. and Wilhelm Friedemann, as well as music by his ancestors, making up the “Old Bach Archive” that dates to a 17th-century polychoral composition by his great-grandfather, Johann Bach. There were also compositions by Georg Telemann and other composers, as well as the originals of Goethe’s letters to the composer Carl Friedrich Zelter. How did this collection end up where no one knew what it was? In 1943, when the bombing of Berlin began, the Berlin Sing-Akademie collection was taken to a castle in Silesia (now part of Poland) for safekeeping. In the spring of 1945, when Soviet trophy brigades began combing the area, a tank driver from Kiev discovered the archive. The KGB arranged to have the material taken to a music conservatory in Kiev, and there it stayed until 1973, when it was moved to the state archive. The Ukrainian authorities have agreed to let the Harvard music department and the Ukrainian Research Institute put the collection on microfilm, Dr. Wolff said. He hopes to compile a manuscript of the collection’s music within a year so that research can go on while the fate of the originals is decided. — NYT Keith K. Klassiks is a student from Singapore who enjoys helping people. He puts his hobbies of music, writing and web publishing to use by reviewing classical pieces for the Vienna Online, besides maintaining his site in Vienna. |

| |||