|

Reality Check

|

The first CG cast of human actors stars in

Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within

|

By Barbara Robertson

|

All Images courtesy of Square Pictures, ©

Columbia Pictures.

|

Pick a science fiction film, any film. Alien, Star Wars, Men in Black,

Fifth Element, you name it. Now, imagine the same film entirely created

with 3D computer graphics-not just the visual effects, but also the people,

cities, landscapes, spaceships, sun, moon, stars, every little bit. That

exactly describes the movie Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within from Columbia

Pictures and Square. The film, which was released July 11, puts synthetic

human actors into roles that could easily have been played by real humans

and places them in completely synthetic sets. Four years in the making,

the film is one of the most ambitious computer graphics projects ever undertaken.

|

"The story could have worked as a live-action film," says Hironobu Sakaguchi,

director of the film and CEO of Square USA (Honolulu), the studio in which

a crew of around 200 people drawn from live-action films, games, commercial

production, animation, and other areas crafted Final Fantasy. "We decided

we wanted to use realistic computer graphics. Our goal was to present the

audience with something they'd never seen before."

|

The decision makes sense given Final Fantasy's starting point as a

role-playing game, and Sakaguchi's role as the originator of that interactive

game. With worldwide sales of Square's nine-part Final Fantasy series totaling

more than 26 million units, according to the company, the studio could

count on a ready-made potential audience of game-players familiar with

the fantasy themes, comfortable with computer graphics characters, and

eager to see what happens next. Sakaguchi did not choose to duplicate characters

from the video games, though. Nor did he choose a storybook style of 3D

animation, such as that in the films Shrek and Toy Story. Final Fantasy

has an original screenplay written by American screenwriters Al Reinert

and Jeff Vintar, and a style all its own.

|

Square's filmmakers describe that style as "hyper" real not "photo"

real, noting that they tried to achieve a heightened reality in the film,

not a replicated reality. Final Fantasy doesn't look exactly like reality,

but it doesn't look exactly synthetic either. It could almost be a live-action

film that was altered for effect. The people at Square believe it could

change the way films are made in the future. "The existence of the film

itself is a great demonstration of what computer graphics can do," says

Sakaguchi, who feels now that people know it's possible to create human

characters on screen, the door is open to new ideas.

|

"It's a shot across the bow in terms of cinematography and traditional

animation," says Gary Mundell, CG Supervisor. "We can do anything we want

now. In this type of filmmaking, there are no limitations on special effects.

There are no limitations on scenery. We can put a human character into

any situation and make it do anything. There is no story that cannot be

told."

|

Square can use words like hyperreal, but it is the photorealistic look

of the film's human characters that is, arguably, the studio's most stunning

achievement. Indeed, several months before the film was released, the men's

magazine Maxim pushed aside flesh and blood women to put Final Fantasy's

star Dr. Aki Ross, wearing a bikini in a seductive pose, on the cover.

And why not? The women on magazine covers will never be anything more than

photographs to most readers anyway, and Aki is as beautiful as the rest.

|

Staging Emotions

|

To direct the cast, Sakaguchi started with detailed frame-by-frame storyboards,

which were scanned and converted into a slide show on an Avid system. Then,

once the voice actors had recorded the script, a layout team began its

work. Using Alias|Wavefront's Maya running on SGI workstations, scenes

were blocked out with simple 3D models of characters and "filmed" with

virtual cameras. "We went to a '70s and '80s style of camera, using [virtual

equivalents of] cranes, steadi-cams, and hand-helds," says Tani Kunitake,

staging director. "We wanted a cinematic style, not a game style."

|

The storyboards and 3D layouts were both sent to the animation and

motion-capture departments. The 3D layouts showed the camera moves and

blocking for the characters timed with the voice recording; the storyboards

showed the subtext, the characters' emotions.

|

"You can't put expressions into a cubic puppet," Kunitake says, referring

to the 3D layouts. And the voice recording used for the 3D layout didn't

tell the whole story either. "Sakaguchi-san would discuss what the scene

is about visually, the relationships between Aki and Sid, Aki and Gray,"

Kunitake says. "He would discuss an emotional path that would happen in

a scene; how the characters feel. We would draw these things putting emphasis

on the story rather than the dialog."

|

Small Changes

|

Trying to turn a 3D model into an emotional and realistic human character,

though, involves a delicate balancing act: If the 3D character doesn't

look human, it doesn't matter whether it moves like a human or not-and

vice versa. But a change to the look can throw the animation off-and vice

versa.

|

"They're both challenging," says Andy Jones, animation director. "We

were always go ing back and forth with the character group about what was

more real, the character's motion or look."

|

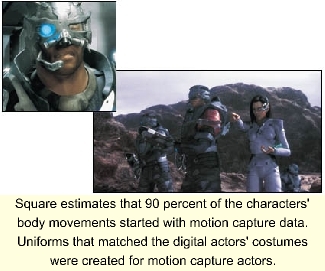

Jones decided to have animators concentrate primarily on the characters'

faces and fingers, assigning lead animators to each character, and also

decided to use motion capture technology to help the animators move the

bodies. "Originally, we thought we'd capture 20 to 25 percent of the human

movement and the rest would be keyframed," says Remington Scott, motion

capture director. "We thought it would just be used for characters when

they're running or moving in large ways."

|

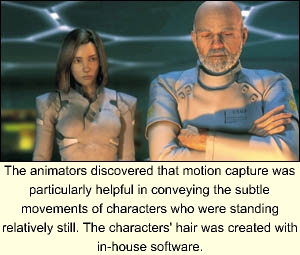

Although it was effective for recording that type of motion, the team

discovered that motion capture became even more valuable when characters

were not moving. "When characters are standing still and starting to talk

and relate to each other, there are incredible subtleties and nuances,"

Scott says. "These things are the essence of what it is to be a human,

to move like a human." Slight movements that could change the mood of a

scene, such as the way a person stands and balances his weight, or shifts

around in a chair were difficult to animate but were relatively easy to

capture. Thus, when the team began casting motion capture performers, they

looked for acting experience. Tori Eldridge, an actress and dancer with

a black belt in two martial arts performed Aki.

|

Square uses a 16-camera optical motion capture system and tracking software

from Motion Analysis; each performer wore around 35 markers, five of which

were in the chest area to capture breathing.

|

Proprietary software made it possible for Jones, Scott, and Jack Fletcher,

voice and motion capture director, to look at the motion capture data applied

to animated characters in Maya within a few minutes. "It wasn't real time,

but it was quick and extremely accurate because we could see the characters

with all the appropriate elements in Maya," says Scott.

|

Ultimately, Scott estimates, 90 percent of the body movements were

based on captured data. That data was fed into an in-house system, which

converted the captured performance into a form that could be used in Maya.

"You can scroll a character back and forth in Maya and see the motion captured

figure moving behind it like a ghost," Jones says. "If you see motion capture

actions or poses you like, you can snap to them, or you can skip sections

and animate those by hand."

|

The characters' bodies were all created in Maya using a representation

of a muscle structure under the skin, and a rig that caused joints to move

bones, which moved muscles, which moved the skin. "The body had to be anatomically

correct," says Kevin Ochs, character technical director, "because we had

to worry about how the clothes would move. To keep things efficient, however,

the team worked with only as much of the body as necessary. "If you saw

a character only from the waist up, he wouldn't have legs in that shot,"

Says Ochs.

|

Moving Faces

|

Once the body performance was finished, the animators began working

on the characters' faces, which were animated entirely by hand. To help

make the skin move realistically, the technical team developed a system

that made it possible for the animators to give the skin a looser feeling

than with shape blending alone. "Blend shapes stretch or shrink the skin

from one point to another, which doesn't allow much leeway for creating

looseness in the skin," says Ochs. "We created a deformational cage that

allows us to represent muscle structure on the fly when the face starts

moving, to give the skin an elastic feel." The technical team used the

same cage, with minor modifications, for all the characters. Basically,

the cage pushes and pulls on several key points depending on the facial

expression, which causes the skin in those areas to move around the points

rather than stretch from one point to another. "We isolated points that

seem to be in constant motion while a person is talking," Ochs says.

|

To create wrinkles, the team decided to use animated displacement maps.

"We realized that one technique was not going to give us the look we wanted,"

Ochs explains.

|

"It's extremely difficult to get the movement of the skin on the face

to look real," says Jones, "especially with how close and unrelenting our

cameras are. Like when a person frowns, little dimples and slight imperfections

appear in the skin that are so difficult to get in a CG character. You

can use animated texture maps, but if they don't perfectly match the motion

and the emotion of the character, something looks off."

|

Lighting affected the look of the animation as well. For example, Jones

explains, there's a tendency for the bottom of the trough of a wrinkle

to be a curve rather than a hard line. The curve causes a reflection of

light, which looks odd inside a wrinkle. Even though the team used techniques

within Pixar Animation Studio's RenderMan as well as in-house tools to

help solve that problem, it was difficult to make the wrinkles look real

when they moved-and there was always another CG idiosyncrasy waiting in

line.

|

"There are so many subtleties," Jones says. "We made a stylistic choice

to have our characters look as real as possible and, given that style,

to get as much emotion as we could out of them. Ultimately, I think the

look side won, especially with faces. It's just so difficult to get the

facial movement to look real."

|

Looking Real

|

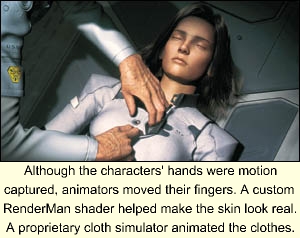

To make the characters' skin look as real as possible, Ochs needed

a method that would render quickly and adapt easily to various lighting

conditions. First, he devised an algorithm that managed the consistent

properties of skin, such as how it reacts to light. Then, the team wrote

a RenderMan shader to create the inconsistent properties. By using texture

maps and procedures, this shader created approximate representations of

skin properties that varied in different areas of the body or as external

conditions changed.

|

Shades of gray from black to white in a texture map used by the shader,

for example, would indicate varying skin thickness to determine how much

light would shine through backlit ear tissue compared to fingers. And,

procedures in the shader managed such skin properties as colors and specularity.

By varying the amount of specularity, for example, the team changed the

look of the skin from oily to dry. "A character's arms would have less

oil than its face," Ochs says. "In some cases, when they're running or

under stress, we would kick up the specularity values so it would look

like they were starting to sweat." Finally, other details such as freckles

and moles were created with painted texture maps.

|

While the skin helped make the digital actors look as if they were

made of flesh and blood, creating believable hair would be the team's crowning

achievement-particularly Aki's hair. Using a proprietary system, animators

could have a simulator automatically generate and animate Aki's hair based

on her movements and settings they entered into the system. For example,

an animator could choose an "Aki running" hair setting that gave the hair

a particular kind of bounce and also specify a strong wind blowing into

her face. Or, animators could use control hairs to create specific actions

such as Aki putting her hair behind an ear. The simulator would then grow

the rest of Aki's hair and move it to match the movement of the control

hairs.

|

The initial hairstyles for the digital actors were all designed with

the control hairs, which were spline-based curves that acted like hair

plugs. The approximately 50 control hairs per head would be output from

Square's system as RenderMan Ri curves, and during rendering would grow

into 50,000 to 80,000 hairs, depending on the hairstyle. To shade the hair,

the team created special algorithms. "The curve doesn't have a rounded

surface, so we had to do a lot of little cheats to give a realistic look

to the hair," Ochs says. "A lot of R&D went into how lighting hits

it."

|

After it came to clothing, though, the animators got a break. When

an animator finished a character's performance, the animation was brought

into a costume file, which housed the character's body and clothes. There,

the animation was attached to the body, and the body's motion would drive

a proprietary cloth simulator. "The entire cloth simulation was done for

this movie in about a year and a half with about four people who would

set up the clothing and give it the properties it needed. It was a very

streamlined pipeline," says Ochs. Because the team designed the software

specifically for this show, they built into the program the features needed

for the movie-leather, rubber, wool, stiff collars, shoulder pads, and

so forth. "It allowed us to stay very clean and quick," Ochs says.

Being clean and quick was important: Although most astonishing, the

human stars weren't the only animated characters in Final Fantasy. The

animation team had to manage crowds of digital people in the cities, herds

of ethereal phantoms, and various kinds of vehicles, ships, and jeeps that

typify a science fiction movie. "Ev erything gets overlooked because of

the humans," says Jones. "But we had to animate anything that moved and

wasn't created with particles or effects."

|

Fantastic Effects

|

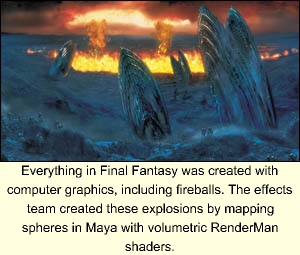

"We have craters collapsing, dust, clouds, fire, explosions, debris,"

says Remo Balcells, visual effects supervisor. "We even blow up a whole

planet." Balcells' team combined techniques used in games with RenderMan

shaders to create many of the natural effects. For example, to create fire,

they used a billboard technique. "We mapped a single polygon with a transparent

texture map that has the colors of fire on it," he explains. "And then

using a Render Man shader, we animated the texture procedurally."

|

To create smoke trails, the crew used a similar technique. "In stead

of a single rectangle, we use many of them mapped onto particles," says

Bal cells. To create the illusion of self-shadowing columns of smoke, however,

they mapped the shadows of simple spheres onto texture-mapped spheres.

Spheres were also used for fireballs created from explosions. "We'd map

the spheres with a volumetric shader and render them," he says. "It's not

a complex technique, but it requires a complex shader."

|

As production progressed, though, the team began to rely on compositing

for many atmospheric effects such as fog, which could be created more quickly

with a compositing program than with rendering. "At the beginning of the

production there was little emphasis on compositing," says James Rogers,

compositing supervisor. "It was seen as something that could add the odd

lens flare." By the end, many of the shots were composites with more than

100 layers. "A lot of people who came from live action like myself are

used to working that way," he says. The team started with Avid's Illusion,

then began working primarily with Nothing Real's Shake and Adobe's After

Effects, with Alias|Wave front's Com poser and Discreet's Flame also playing

a role. "We used anything we could get our hands on," says Rogers. "I think

that we ended up with an average of 16 layers per shot. Early last fall,

after he took on the job of CG supervisor, Mundell did an inventory of

shots that had to be completed and realized there were far too many frames

to render. By ad ding WAMnet service to the studio's 1000 Linux-based Pentiums,

300 SGI Irix CPUs, 160 Octanes, and 3 Origins, and by isolating areas that

were taking more time than others and optimizing the workflow process,

the team was able to finish three weeks ahead of schedule. "We found that

Aki's hair was taking 20 percent of all our rendering time," Mundell says,

for example. So they optimized the hair rendering and also changed such

things as texture map sizes where possible. In terms of workflow, they

tried to reduce the rendering times for shots in process and the amount

of approvals needed for each shot. "Next time it will be a lot easier,"

he says.

|

Like many people at Square, Rogers and Mundell believe that the film

is going to cause a paradigm shift. "Filmmaking has always been driven

by technology, from black and white to color, from silent to sound," Rogers

says. "I think this is one of those things. It's not necessarily the right

way to make a film, but I think it's quite significant. Filmmaking is ruled

by economics, and as the cost of technology decreases, this style of filmmaking

may become more popular. Instead of flying a crew to location x you could

create a virtual location. Instead of calling back actor x, you could do

a cutaway shot in the computer in post production."

|

Recently, a Hollywood agent who wants to represent Aki approached Sakaguchi,

a development he welcomes. "She could be hired for commercials, or other

movies," he says. Thinking about those implications could put a regular

human into hyperdrive. Would she appear as Dr. Aki Ross, the scientist,

endorsing a product? Or as the actress who played Dr. Aki Ross? And who

is that actress anyway? Is she Ming-Na, Aki's voice, Tori Eldredge who

moved her body, the modelers who built her body, the TDs who gave her flesh

and blood, or Roy Sato, the lead animator who gave her expression? Does

she exist without all these people working in concert?

|

Whether Aki becomes a star in her own right (whatever that is), there's

no question that photoreal or hyper real or simply realistic digital actors

will appear in future live-action and animated movies in important roles.

Perhaps this will open the door to actors and actresses for whom the camera

is not a friend, allowing them to become stars by stepping into camera-friendly

CG bodies and speaking through the lips of CG characters. It's easy to

imagine all sorts of possibilities-movies in which one actor plays many

roles voiced by multiple actors . . . or multiple actors playing many roles

all voiced by one actor. In the end, will the digital actors be the stars

or the people driving them?

|

It's possible that at this moment in time, the answers don't matter.

What matters is that because of Final Fantasy, we are thinking about it.

|

|

Barbara Robertson is Senior Editor, West Coast for Computer

Graphics World.

|

Computer Graphics World August, 2001

Author(s) : Barbara Robertson

|

|

|