|

Raptor Redux

|

| ILM revitalizes the raptors, T rexes, and other digital dinos in

Jurassic Park III |

By Barbara Robertson |

© 2001 Universal Pictures. Photo credit

ILM. |

When the crew at Industrial Light & Magic (San Rafael, CA) was

asked to recreate the dinosaurs from Jurassic Park for the third time,

they did what any effects crew would try to do: produce something more

incredible than last time . . . or the time before. |

When the crew at Industrial Light & Magic (San Rafael, CA) was

asked to recreate the dinosaurs from Jurassic Park for the third time,

they did what any effects crew would try to do: produce something more

incredible than last time . . . or the time before.

|

In the Universal Pictures film, directed by Joe Johnston and released

July 18, moviegoers once again watch prehistoric dinosaurs terrorize a

few intrepid visitors to Isla Sorna, the original Jurassic Park location.

To help enliven the sequel, ILM developed new techniques for the visual

effects in two main areas: The team created a simulator that moves the

digital dinosaurs' skin across muscles and bones in a realistic manner,

and they made breakthroughs in integrating the dinosaurs with the environment.

|

"It's not enough just to do the dinosaurs," says Mitchell. "Now the

big thing is what you do to make the dinosaurs part of the scene."

|

Physically Fit

|

To help the dinosaurs look like they be longed in the environment,

the effects team focused on two issues: matching the CG dinosaurs to the

animatronics, and creating photorealistic natural elements-including, for

one dramatic sequence, an entirely CG world.

|

Unlike the earlier movies in which the camera would cut from animatronic

to CG dinosaurs, in Jurassic Park III, both types of dinosaurs appear in

the same scenes, sometimes nose to nose. For example, during a fight between

a spinosaurus and a T rex, sometimes the T rex is CG, sometimes animatronic;

sometimes the spino is CG and sometimes animatronic. It's im possible to

tell which is what, even in close-ups. In another scene, CG and animatronic

raptors surround actor Sam Neill. "It's amazing to be on the ground, right

in front of a 12-ton creature and see it power up," says Mitchell of the

animatronic. "It puts you into the moment."

|

To create CG dinos that looked as real, ILM's painters used photographs

of the animatronics as reference for painted texture maps, and created

displacement maps so the renderer would carve surface geometry into a lizard-like

texture.

|

The effects team got a surprise, though, when they looked at the first

live-action plates. In reference photos, the animatronics were brownish,

but lights on the set had given them a bluish cast. Moreover, colored filters

had created patterns in hues of green, orange, and blue that slid across

the animatronics' skin as they moved in the live-action plates, to give

the impression of a canopy of jungle foliage. "We had to match the same

color space," says Samir Hoon, sequence supervisor. "So, we ended up using

ambient occlusion."

|

This rendering technique, developed at ILM for Pearl Harbor (see "War

Effort," June 2001, pg. 22) to simulate diffuse light in an environment,

added colors from the plate to the rendering of the dinosaurs' skin. To

make ambient occlusion useful for Jurassic Park III, the team had to extend

the technique so that it worked with deformable, animated creatures and

would handle motion blur and displacement-effects not needed in Pearl Harbor.

The ambient occlusion technique worked so well it was used for all the

sequences. Sometimes, ambient occlusion and reflection maps provided all

the light needed for a scene.

|

For example, in one scene the wet body of a spino walking through a

lake reflects a fire burning in the foreground. "We would run the reflection

map and the ambient map on every frame from the plate and get the flickering

lights and flames on the spino automatically," says Christophe Hery, CG

supervisor. "It was a major breakthrough."

|

"The ambient technique is not the only technique you want to use, but

it's a great help," he adds. "It freed the technical directors so they

could focus on adding key lights and secondary lights to make the creatures

look beautiful instead of spending time placing fill lights." All the CG

creatures and scenes in Jurassic Park III were rendered through Pixar Animation

Studio's Render Man, with Mental Images' Mental Ray helping with the ambient

occlusion.

|

Plant Happy

|

Fitting the dinosaurs into the environment also meant helping the beasts

look as if they were interacting with the environment. When a dinosaur

crashes through the forest, it moves trees and plants aside, tramples grass

underfoot and splashes water when its big foot steps in a puddle. In the

first Jurassic Park films, people on location or on the set moved trees

and plants with rigs, and painters removed the rigs from the plates later.

Thus, animators had to position their digital dinosaurs so that it looked

like the animals were interacting with the trees and plants in the plate.

This time, though, the animators created the performances they wanted and

the technical team fixed the plate to match.

|

In the sequence with the two dinosaurs fighting, for example, dozens

of CG elements added after the dinosaurs were animated helped make the

live-action environment livelier. The effects team put a puddle under a

dino's foot, added little animals that scurried away from the frightening

beasts, showered the thrashing dinos with falling leaves, and added plants.

"We've reached a point where the plate is almost secondary to us," says

Hery.

|

Throughout the film, the dinosaurs brush aside vines that exist only

in the computer and move plants that are half digital and half real. "We

were really plant happy in this movie," says Hoon. In one shot, for example,

all the ferns in the live-action plate were replaced with CG ferns so the

plants would move automatically when a CG raptor ran through them.

|

To create plants, the team used Alias|Wavefront's Maya Paint Effects

running on SGI workstations. "Paint Effects doesn't motion blur properly,

so we had to come up with solutions for that," Hery says. "But it's quick.

You just draw brush strokes and grow leaves out of that."

|

Rather than use the dynamic engine in Paint Effects to animate plants,

the team developed a separate system based on particle dynamics "When any

part of the raptor touched a plant, it would respond correctly," Hoon says.

Rather than use the dynamic engine in Paint Effects to animate plants,

the team developed a separate system based on particle dynamics "When any

part of the raptor touched a plant, it would respond correctly," Hoon says.

|

Here's how it worked: First, they drew a plant in Paint Effects and

separately, a curve (a spline) the same height and then attached the two.

Next, they converted the spline into a soft body, turning each point on

the spline into a particle so that it would respond to collisions using

typical particle dynamics. Thus, when a particle collided with a piece

of geometry, it moved; and when a particle moved, the Paint Effects plant

followed.

|

| To render the plants, the team borrowed an idea from ILM's crowd pipeline.

"We created libraries with instanced geometry for vines and leaves. Instead

of instancing cycles of animated creatures, we instanced cycles of moving

leaves," Hery says. |

| Grand Canyon |

If it's possible to create plants photorealistic enough to live alongside

plants filmed on location, why not create an entirely synthetic location?

For much of the so-called aviary sequence, the team did exactly that. "I'm

partial to this sequence because it's so fast paced," says Mitchell. "You're

flying alongside pteranodons."

|

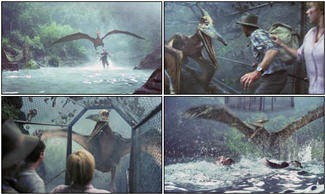

The 15-minute sequence takes place in a 100-acre, fog-enshrouded canyon

with steep, craggy, 300-foot walls, down which waterfalls cascade into

a rapidly flowing river. It's the pteranodons' aviary and nesting ground,

and much of the 15-minute sequence was created entirely with computer graphics.

|

At one point during the sequence, a pteranodon walks out of the fog,

plucks the child, Eric (actor Trevor Morgan), off a bridge across the canyon,

and flies with him dangling from its talons to a nest of hungry fledgling

pteranodons.

|

he actor was filmed on a bluescreen stage hanging from bird-like legs,

which were moved on a rig. To give animators freedom to move the bluescreen

boy in 3D space, the effects team attached a "card," (a polygon), to the

CG pteranodon's feet. Then they mapped the bluescreen character onto the

card. The rest of the environment was created with Avid's Soft Image 3D

models and RenderMan shaders.

|

The shaders do most of the work. In fact, a view of the undressed geometry

looks like a bad virtual reality scene. The nest sits on tall, garishly

colored cylinders, the walls look like flat planes, the boy in an egg-shaped

slice of bluescreen hovers above the animatronic nestlings, and it's hard

to believe this will become a photorealistic landscape.

|

The shader, masterminded by technical director Toan-Vinh Lee, turned

the canyon walls into rocks, created waterfalls and a river below, and

grew ferns and foliage on the walls. Fractal-based displacement created

the crevices and rock formations. Plants were grown in the walls based

on proximity fields. "You paint a map that pinpoints where you want the

plants to be grown," says Robert Weaver, sequence supervisor. Specular

noise created the waterfall and a canopy with a grid pattern was formed

from simple patches, all in RenderMan.

|

To create a dense fog that matched what the fog machine generated on

stage, Hery opted to work with spheres in Soft Image to position the fog

in 3D space. He then rendered the spheres with simple RenderMan shaders

that used fractal noise-a faster process than if he'd used particle or

volume simulation.

|

In addition to the foggy canyon, the sequence also had CG water created

with a combination of a fractal-based shader and particle mist, a completely

computer generated parasail, a sort of parachute-like flying ma chine developed

by technical director Nigel Sumner, and many flying CG pteranodons.

|

Skin Care

|

The film, of course, had a host of other prehistoric digital animals

ranging in size from two-feet to 51-feet tall, all modeled in Alias|Wavefront's

Power Animator and ILM's ISculpt. In addition to velociraptors, spinosauruses,

T rexes and pteranodons, the film also starred CG brachiosauruses, ankylosauruses,

compsognathuses, parasaurolophuses, corythosauruses, stegosauruses, triceratops,

and ceratsauruses.

|

Making all these dinosaurs move realistically took the efforts of the

animation team, led by Dan Taylor, but the skin simulations created by

the technical teams helped. Sebastian Marino, CG software developer, based

the new skin simulation techniques on volumetric simulations developed

by John Anderson, CG scientist, that were first used for The Mummy.

|

"Basically what we simulate is the volume of the skin and essentially

the fat layer of the creature," says Marino. A three-dimensional point

mesh, in which any vertex could connect to any number of other vertices,

created the simulation.

|

This "flesh mesh" has the characteristics of foam and Jell-O. Like

foam, when one end of the mesh is squeezed, it compresses but the other

end doesn't get larger, and when the pressure is released, the mesh returns

to its original shape. And like Jell-O, it jiggles.

|

To create the simulation, a dinosaur's volumes-its torso, arms, legs,

and tail-were filled with the mesh, and the mesh was linked to the creature's

primary motion. "It's as if the mesh is attached to a centerline down the

volumes of the creatures," says Tim McLaughlin, creature supervisor. "As

the critter moves, the mesh goes along for the ride."

|

The amount the mesh moved and jiggled during that ride depended on

various stiffness and damping parameters and on whether there were obstacles

such as muscles or bones in its path. The mesh contoured over muscles and

bones that pushed it from one place to another as they moved-imagine punching

a foam pillow. Also, waves of motion propagated through the mesh-imagine

shaking a bowl of Jell-O.

|

Thus, the simulator caused the belly of the T rex to shake like Jell-O;

and, at the other end of the spectrum, caused muscles to ripple under the

skin of the raptors' athletic bodies. "As the mesh gets pushed from one

place to another, you can see what's driving a creature, which is something

you never get with enveloping," Marino says. "First, you see muscles flexing,

and then the leg goes forward and extends. As the creature steps down,

you see the muscles tighten up and see that movement affecting the fat

layer."

|

The skin sims were not used for every shot-motion blur and camera shake,

for example, would often hide the effect. When they were used, however,

the team discovered the simulator had a positive effect on textures: It

prevented texture stretching. Because it stretched the skin globally rather

than locally, the skin moved more naturally. "The simulations didn't alter

the way the models were painted, but the textures looked better when the

dinosaurs moved," says McLaughlin.

|

All told, ILM created 406 shots for the film, nearly eight times the

55 visual effects shots created by the studio for the first Jurassic Park.

That movie convinced Hollywood that movies with computer graphics creatures

could be both cost-effective and box-office hits. "We were breaking ground

then, putting detail into reptilian skin textures, creating realistic animation,

faking how skin reacts to the way bones move," says Mitchell, who was a

technical director for the original Jurassic Park.

|

| Eight years later they've done it again. ILM improved on the original

breakthroughs and pushed the state of the art further with the skin simulations

and by intermingling CG dinosaurs with animatronics. Moreover, while the

first Jurassic Park demonstrated that CG dinosaurs made production sense,

this one shows that totally synthetic natural environments do, too. "You

can always make an environment that's stylized," says Weaver. "But if you're

trying to sell it as photoreal, you've entered a new ball game. To be able

to do that within a budget that's feasible from a production standpoint

is really important."

|

Barbara Robertson is Senior Editor, West Coast for Computer

Graphics World.

|

Computer Graphics World August, 2001

Author(s) : Barbara Robertson |

|