Dionÿsische Fantasie (The

Dionysian Fantasia)

Hausegger wrote the Dionysian Fantasia between Christmas of

1896 and spring of 1897. He led its premier with the Kaim Orchestra in

The hero sees the clash of combat

and eagerly joins in. While in the fray, he

sees a

vision of Death, which he tries to banish. He wanders through an arid

valley,

full of the miasma of death. Amidst the desolation, he sees a pathway

out,

blocked by the Specter. Yet, a renewed inner life force flares; he will defy

Death. It crumbles at his challenge. He

walks the shining path, which broadens

as he ascends, a song of victory

rising from his heart. From the summit, even if

dying in ecstasy, the hero can cry “Thou world, I love

thee!”

These thoughts yielded a three-part

design; first, heroism - a march, with a calmer trio. Then, the valley of death

- a slower

section. Finally, through a carefully prepared transition segment, a

combination of the artist’s “Let it become!” - a

jubilant finale melding some of the work’s major themes.

Barring the occasional coincidence,

Nietzsche’s work seems, to me, more of an internal inspiration to Hausegger

than any audible influence that listeners might catch. No doubt, he readily

responded to the notion that, as Kaufmann puts it “From tragedy…one can affirm

life as sublime, beautiful and joyous, in spite of suffering and cruelty.” As

commentators on Strauss’ Also Sprach Zarathustra have found, trying to

match a philosophical text with a musical work is chancy at best. Hausegger’s

prefatory poem seems a better bet for those needing a point-to-point concurrence

between the program and the music. The Dionysian

Fantasia lasts about 25 minutes,

using the following instrumentation:

Picolo,

3 flutes, 3 oboes, English horn, 3 clarinets, bass clarinet, 3 bassoons

(contrabassoon)

4 horns,

4 C trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba

Tympani,

3 percusion- bass and snare drums, crash cymbals, triangle, gong and

glockenspiel

2 harps, strings. In his Aufklänge,

he specifically notes 62 strings (32/12/10/8), which I’ll use as an effective

working number

The work begins with a slow

introduction. As with Robert Schumann’s Second Symphony, Hausegger’s slow

introductions not only set a mood, they’re also a quarry from which the

composer mines many of the most important themes. The music first sounds as if

it were pulling itself up from the (chromatic) depths toward its basic D major tonality.

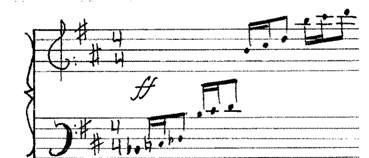

The tympani rhythm is also important. (Ex. 1 next page)

Ex. 1

As the

music gathers weight, the tympani figure in Ex. 1 gains motivic interest

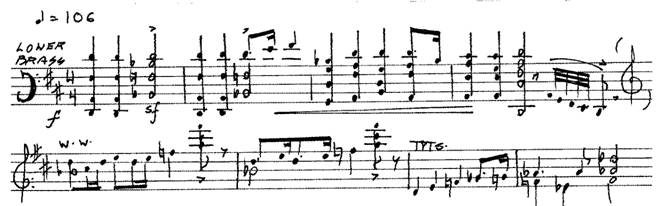

Ex. 2

as

well as a trumpet theme, the Motiv of Life.

Ex. 3

The introduction

continues apace, finally halting on a dominant 7th, before launching into the march theme of the work’s first section. This nominally D

major passage shows how, at 24, Hausegger had already acquired Wagner’s way of twisting

in and out of remote keys.

Ex. 4

The

march then combines with a more lyrical, yearning theme on the violins.

Ex. 5

The

tempo quickens as these elements build to a climax at which the Death Motiv (obviously

derived from Ex. 2) halts its progress.

Ex. 6

In the

high winds and strings, we hear a brief phrase from what will eventually be the

Song of Love:

Ex. 7

The

Death Motiv repeats, as if to impede any forward motion. At length, the music

becalms and the solo clarinet begins the trio of the march

section, its theme a continuation of Ex. 7

Ex. 8

Another

variation of this theme, in canonic imitation, further hastens the pulse.

Ex. 9

Propelled

by rising sequences, the trio gathers momentum, combined with versions of Ex.

3, both rhythmically and orchestrally augmented. A descending chromatic version

of Ex. 7 returns us to the main march theme, this time alternated with the Love

Theme. At the same time, trombones and tympani give a sense of menace by

relentlessly barking out the Death Motiv in both diminished and augmented

rhythms, till a decrescendo leads toward

B minor and the next part of the poem.

The second major section of the work

then begins, with a flute theme, extended by the solo oboe, then the violins.

Ex. 10

This is

gradually taken up by the rest of the orchestra, only to be halted by an

agitated burst, collapsing on a diminished 7th chord with the Death Motiv in E

flat minor on the tubas and basses. This could, I suppose, express Nietzsche’s

passage in The Birth of Tragedy that

“at the very climax of joy, there sounds a cry of horror,

or a yearning lamentation for an irretrievable loss”.

The Death theme slinks around on the

solo tuba, till eventually, Ex. 3, the Theme of Life emerges on the trumpets (3/4

time, C major) and expands through several keys till the mood again grows more

tranquil. Divisi violins and violas play a soft chordal passage, as much a

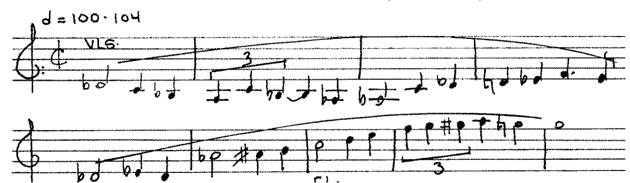

texture as a theme. (Ex. 11, next page)

Ex. 11

Above

this, a “transfigured song” arises on the solo violin, announcing the awakening

of renewed life. A derivation of this theme forms the prime subject of the

final section.

Ex. 12

The pace

quickens and again, the Death Motiv appears in rising sequences, till at

length, the trumpets counter with the Theme of Life, A major, in broad

augmentation. As if still trying to halt any forward motion, Death again rises

up, now exerting its dominance in a full melodic statement.

Ex. 13

This

segment peaks with the Death Theme in expansive 5/4 bars, climaxing against the

Motiv of Life now in a ringing D major on the trumpets.

The principle theme of the final

section derives from the violin solo of Ex. 12, transformed into a swinging

tune in 6/8, with scherzo-like accompanying figurations. (Ex. 14, next page)

Ex. 14

After a

decrescendo, the flutes and clarinets begin a quieter variant of Ex. 8, combined

with the chordal theme of Ex. 11, played pizz. on the divided strings in the

dominant key of A major. The final bars build to a

jubilant song of victory, with Ex. 12 combined with trumpet fanfares based on

Ex. 7 for a grand reprise. A Stentorian blast in the bass

instruments, reminiscent of Death, but actually from Exx. 7 and 8, makes one last try to halt the celebration, only to be

swept away in an ascending rush of D major.

The Dionysian Fantasia has all the earmarks of youthful exuberance. The

orchestral palette shows the hand of a born symphonist, with its brave, yet

often subtle colorings. Its themes, despite some real ingenuity in their

transformations, variations and interrelations, don’t quite reach the epic

ambitions of the program. One reluctantly sides with Dr. Wilhelm Zentner’s characterization

that “despite original details and overpowering energy, greatness of ideas is

lacking. The elements of an outstanding personal style are present.”

Despite any immaturities, the work

established von Hausegger as a charter member of the