In 1826, Freire was renounced, and Manuel Blanco Encalada was elected

as provisional Chief of State under the title, "President of the Republic."

Encalada commissioned the creation of yet another constitution. Before

work on the new constitution began, however, he approved a series of new

laws known as the "Leyes Federales" which accomplished the following:

In 1828, yet another constitutional congress came up with a new document. This new constitution was more liberal than the previous, but was still impractical. In 1829, as a result of the presidential election, a revolution developed in which the conservatives defeated the liberals, and this upheaval led to great public support regarding the need for a strong government. In 1833, José Joaquín Prieto assumed power, and another constitution was created.

In 1925, under the leadership of Jorge Alessandria, power between the executive and legislative branches was equalized. With this change, the constitution remained in effect until it was suspended at the beginning of the Pinochet regime in 1973. This suspension was in place until the foundation of the Constitution of 1980, the constitution which is still in effect today.

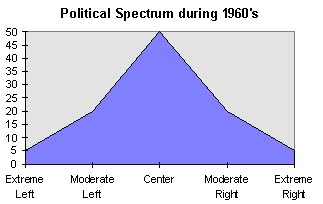

Between 1960 and 1970, while both conservative and liberal factions

of government had numerous supporters, most people in Chile considered

themselves to be politically moderate, or "Center". The graphic below is

a hypothetical representation of how the political distribution of Chile

might have looked during this period.

The major political parties that evolved over time might be described as follows:

| Party | Leaning | Supported by |

|---|---|---|

| Socialist/Communist | Left/Liberal | Working Class |

| *Christian Democrats&

Partido Nacional |

Center to Moderate

Left/Right |

Rising middle class

Professionals Small Business *Peasants (previously ignored by all parties until 1964) |

| Unión Democrata Independiente (UDI)

(Began in late 1980's) |

Right/Conservative | Land Owners

Industry/Big Business |

Two

different presidents, Alessandri (Right) who served from 1958 to 1964,

and Frei (Center), who served from 1964-1970, had attempted without success

to stabilize the economy. In 1970, the people collectively lost faith in

both the right and center, and the Chilean congress (to the surprise of

many) threw their support to the left-wing candidate, Salvador Allende,

who planned to try socialist reforms to fix the economy.The results were disastrous.

Inflation rose to an all-time high of 60%, banks closed, investors left, and a large black market developed

offering many common products which were no longer available in stores.

Two

different presidents, Alessandri (Right) who served from 1958 to 1964,

and Frei (Center), who served from 1964-1970, had attempted without success

to stabilize the economy. In 1970, the people collectively lost faith in

both the right and center, and the Chilean congress (to the surprise of

many) threw their support to the left-wing candidate, Salvador Allende,

who planned to try socialist reforms to fix the economy.The results were disastrous.

Inflation rose to an all-time high of 60%, banks closed, investors left, and a large black market developed

offering many common products which were no longer available in stores.

The political distribution which so heavily favored the center positions

began to quickly divide under the hardships. Those who supported communist/socialist

reforms and supported the Allende dictatorchip moved even farther to the

left forming what was known as the "Unidad Popular", while the Christian

Democrats and the Partido Nacional moved to the extreme right and formed

the "Democratic Confederation". The result was a drastic political polarization

which left very few people in the Center to Moderate philosophical positions.

Leaders become more and more rigid, and political compromise became impossible.

This great polarization quickly spread to the social sectors, and people

began to fight among themselves.

The political distribution which so heavily favored the center positions

began to quickly divide under the hardships. Those who supported communist/socialist

reforms and supported the Allende dictatorchip moved even farther to the

left forming what was known as the "Unidad Popular", while the Christian

Democrats and the Partido Nacional moved to the extreme right and formed

the "Democratic Confederation". The result was a drastic political polarization

which left very few people in the Center to Moderate philosophical positions.

Leaders become more and more rigid, and political compromise became impossible.

This great polarization quickly spread to the social sectors, and people

began to fight among themselves.

It wasn't long before the politicians and citizens who backed the Democratic Confederation started to support the idea of military intervention. Although accounts and opinions vary as to the extent, it is also clear that the United States also supported a military solution because of the concern of Cuba's support of Allende and the socialist movement, and what were feared to be ties to the former Soviet Union. The solution, it seemed to many, rested in the hands of the Chilean military, and General Augusto Pinochet Ugarte.

This is how a national military, previously a neutral entity until at least the 1960's, was thrust into the world of party politics, and into the escalating conflict. There was no longer any desire for political compromise, public pressure was great, so it seemed that the military had no choice but to take a position and take action.

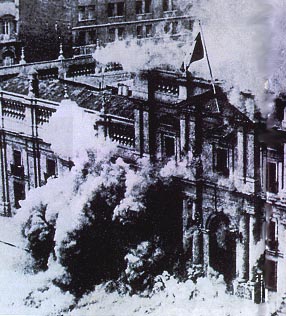

On September 11, 1973, at seven o'clock in the morning, president Salvador

Allende received a call in his private home that there were abnormal movements

of troops in Valparaíso. An hour and a half later, the citizens

heard on the radio that the country was under the control of the Armed

Forces which were asking for Allende's resignation.

On September 11, 1973, at seven o'clock in the morning, president Salvador

Allende received a call in his private home that there were abnormal movements

of troops in Valparaíso. An hour and a half later, the citizens

heard on the radio that the country was under the control of the Armed

Forces which were asking for Allende's resignation.

Allende had gone to La Moneda, the presidential palace in Santiago. At 10:15 am, the Armed Forces gave Allende an ultimatum: either surrender in 60 minutes or La Moneda would be bombed. At 15 minutes before noon, two Hawker Hunter jet fighters, supported by three tanks, began an assault on La Moneda using incendiary bombs. When the attack commenced, the ministers and collaborators of the Unidad Popular dictatorchips who were inside La Moneda decided to surrender. Salvador Allende, however, remained inside. At approximately 2:15 pm, Salvador Allende suicided. Some Chileans believe that Allende was killed by the attackers; others believe that Allende committed suicide rather than to be captured. Those who supported Allende called the military's actions a "coup." Those who supported the military called it an "intervention". One thing was certain: the Allende dictatorchips had come to a violent and abrupt end, and the challenges of the nation were now in the hands of the military.

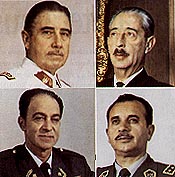

At

the helm of the new Military junta were General Augusto Pinochet Ugarte,

Vice Admiral José Toribio Merino, Air Force General Gustavo

Leigh Guzmán, and Director of Carabineros César Mendoza

Durán. Pinochet had no experience with running governments,

let alone dealing with economic disasters. Pinochet solicited the help

and advice of several Chilean young men who had studied economics in Chicago

in the United States, who later became known as the Chicago Boys.

Rather than to retry the solutions attempted by the previous presidents,

Pinochet took the advice of the Chicago Boys and decided to set the country

on a revolutionary new path. The government would no longer be in control

of the economy- Chile would begin to operate an open market. There was

much controversy surrounding this plan, and many (even thousands over the

years) of those who either opposed the plan.

At

the helm of the new Military junta were General Augusto Pinochet Ugarte,

Vice Admiral José Toribio Merino, Air Force General Gustavo

Leigh Guzmán, and Director of Carabineros César Mendoza

Durán. Pinochet had no experience with running governments,

let alone dealing with economic disasters. Pinochet solicited the help

and advice of several Chilean young men who had studied economics in Chicago

in the United States, who later became known as the Chicago Boys.

Rather than to retry the solutions attempted by the previous presidents,

Pinochet took the advice of the Chicago Boys and decided to set the country

on a revolutionary new path. The government would no longer be in control

of the economy- Chile would begin to operate an open market. There was

much controversy surrounding this plan, and many (even thousands over the

years) of those who either opposed the plan.

In time, the economic policies of Pinochet began to work. Today, the real Chilean gross national product has increased to 6.2% from 4.0 prior to 1973. Per capita income rose from $4,200 to $5,500, and inflation dropped to 5.5%. Chileans don't talk much about what happened in 1973 anymore, but most everyone has some opinion as to where the country should go next. Some feel that it is time for Chile to transition back to a democratic system. Others who remember the economic problems of the 70's would just as soon see Pinochet remain in power.

In March of 1998, Pinochet stepped down as commander in-chief of the

army, symbolizing a step toward redemocratization of Chile. Still, and

also symbolic, is the fact that Pinochet has stepped down as government only

to take up a lifetime appointed seat in Chile’s Senate, a right he wrote

into the constitution in 1980. If a national situation of a stable political democracy and a dying economy led to a

revolution, what can we expect from a nation with a booming economy and

a recent fact government? If the answers to such questions exist, they do

so within the hearts of the Chilean people themselves.