..To Ancient SDA's ............ To "What's New?"

Dateline Sunday U. S. A.

by

Warren L. Johns

Issued with the author's permission

[21]

Chapter 3.

"BUILDING

A WALL

OF SEPARATION

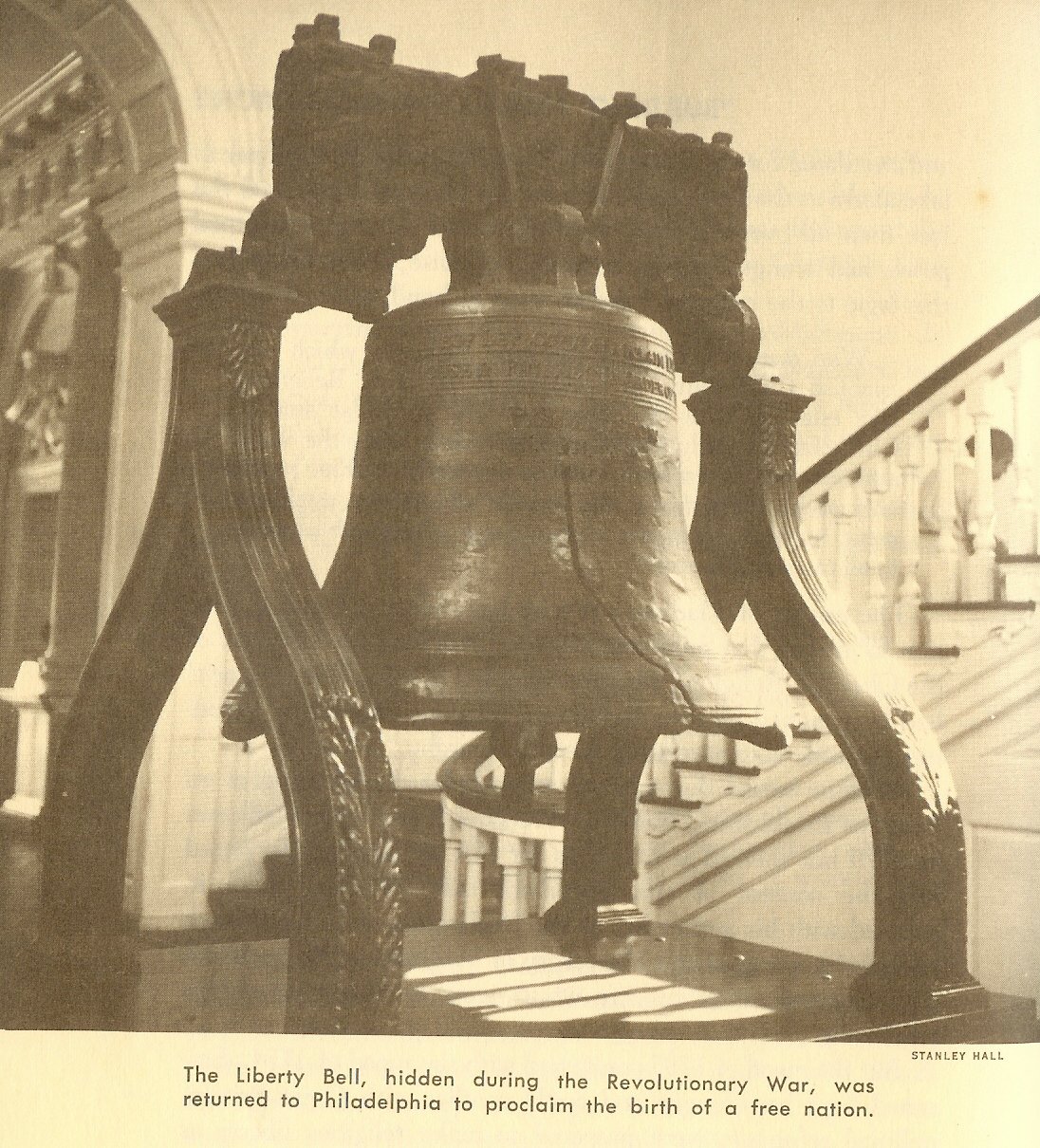

Dateline: PHILADELPHIA, November 3, 1791. Today the first ten amendments to the United States Constitution became a part of the supreme law of the land. The first sentence of the first amendment rejected centuries of precedent, guaranteeing that religion was to be neither the slave nor the master of the state.

Thomas Jefferson observed, "I contemplate with sovereign reverence that act of the whole American people which declares that their legislature should 'make no law respecting an establish merit of religion or prohibiting the free exercise therof,' thus building a wall of separation between church and state."1

This was no paper philosophy. Though Christianity flourished in the minds of the citizens and leaders of the new nation, neutrality in matters of religion had become official government doctrine. This philosophy appeared in the "Treaty of Peace and Friendship" with Tripoli, executed November 4, 1796 during the administration of George Washington. This document declared that "the government of the United States of America is not, in any sense, founded on the Christian religion."2

A revolution in both thought and action had taken place. A noble experiment in civil and religious liberty had been conceived.

[22] Centuries marked with martyrdoms and bloody persecutions foisted on ancestors across the Atlantic, offered a shabby chronicle. New World settlers recalled the lions of the Roman coliseum; the Spanish Inquisition; the massacres of the Waldenses in their mountain hideaways; the Tower of London; the "holy" wars; the rack, the screw, and the stake; fines, imprisonments, and executions.

Overzealous early colonists had not been reluctant to use the dock, the pillory, and the lash. Yet, paradoxically, the stringent character of the colonial Puritan was one factor which assured the eventual demise of government by clergy. As early settlers struggled to survive in a new and hostile land, stalwart individualism was essential, and a self-reliant citizenry chafed under the heel of oppressive clericalism. Citizens nearly succeeded in preventing the clergy-inspired hanging of George Burroughs, and even the teachings of Roger Williams found sympathetic Puritan ears. The scope of the land itself encouraged freedom. Where political or religious ostracism had occurred, there was always the refuge of the new frontier.

The fifty-five men who met in Philadelphia in 1787 to construct a new system of government had been exposed to the philosophical thought of theorists like Locke, Montesquieu, and Voltaire, who wrote from philosophical bent and from bitter experience as well. Ideas such as "That government which governs least, governs best," and "I may disagree with what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it," appealed to the founding fathers.

Finally, inherent in the origins of the American Revolution was the diversity of the national heritage. Patterns of religious thought were equally diverse:

The growth of religious freedom might have had a different story but for America's novel situation of having no majority religion. Puritan New England, which clung longest to the old intolerance, and Anglican Virginia, which was hardly less intolerant in the early days, were the only areas dominated by single religious groups. [23] The Quaker colonies, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware - none of which had religious establishments, came nearest, after Rhode Island, to realizing complete religious liberty, but the Proprietary colonies in general developed liberal tendencies. Business considerations would naturally operate to induce Proprietors to grant a measure of tolerance, for they needed to attract industrious settlers and promote peace and prosperity. This was at least partly responsible for writing liberty-of-conscience clauses into the charters of New York, New Jersey, the Carolinas, and Georgia.

Aside from the increase of dissenters, the growing number of the unchurched was a factor. Even in Puritan New England the majority of the masses were not church members, and the wave of popular resentment against the magistrates prevented the continuance of severe persecution of Quakers. Indeed, the increasing strictness of the Puritan legislation attests the inability to enforce such laws on the population at large.3

Stephen Mumford, a member of the Bell Lane Seventh Day Baptist Church in London, settled in Roger Williams's Newport, Rhode Island, colony in 1664. When five members of the Newport First Baptist Church joined the Mumfords in worshiping on the seventh day of the week rather than Sunday, they were called before the church officials to answer for their deviation. Samuel Hubbard, one of the five, later wrote the details of his appearance: "I answered, 'I believe there is but one God, Creator of all things by His word at first and then made the 7th day and sanctified it; commanded it to be kept holy, etc., that Christ our Lord established it, Math 5 [Matthew 51; the holy apostles established it, did not say it was holy, but is holy, just and good.'] 4

Seven years after this brush with established religion, the Baptist group founded its own meeting place in Newport and counted among its members some of the most prominent, influential citizens of Rhode Island. Samuel Ward, Rhode Island governor and first colonial governor who refused to enforce the 1765 Stamp Act, was a Seventh Day Baptist and a delegate to the Continental Congress that met in Philadelphia on September 5, 1774.

[24] Had he not died on March 26, 1776, he likely would have been one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence. The case of Governor Ward and the Seventh Day Baptists is a clear illustration of the position of minority groups in some colonies:

While full freedom of belief was not legally protected in any of the colonies at the start of the Revolution, and most of them had an established church supported by the government, minority groups and nonconforming individuals were in fact granted considerable leeway. Catholics were strong in Maryland; Quakers, in Pennsylvania. In New England, the evolution of a Congregational doctrine had moved toward freedom of conscience for more than a century, so that there was a kind of paradox in the legal establishment of a church so nearly democratic in its organization. The supremacy of the Anglicans in the South, moreover, was weakened by the fact that theirs was the official church of England in a period when independence from the mother country was about to become the paramount fact of current history. For, whatever their doctrinal differences in religion, all of the Founding Fathers were political revolutionaries, determined to enact a new formulation of the idea of government by consent of the governed.5

With the Baptists, Quakers, and Presbyterians moving into the South, the time had come to consider more carefully the establishment of religion in a political context. These minorities were present in Virginia, a colony dominated in its religious affairs by the Church of England and the home of some of the most astute political leadership of the Revolution, George Mason, James Madison, and Albermarle County's Thomas Jefferson.

Jefferson believed that complete personal freedom of conscience was inseparable from "the principle of majority rule." This principle "depended on the premise of a well-informed public, each member of which could choose among moral or political alternatives with absolute freedom from mental coercion. This is the key to Jefferson's lifelong insistence on complete separation of church and state."6

[25] The Virginia House of Burgesses, meeting in Williamsburg, was a forum for issues affecting civil and religious liberty. Here constant demands were heard for the recognition of basic human rights. A steady stream of petitions and requests to protect these rights flowed to the legislature from Virginia citizens. By 1776, the year that James Madison of Port Conway arrived as a delegate, the House of Burgesses was reviewing the entire structure of Virginia government.

Madison served on a committee to draw up a bill of rights which would provide the philosophical base for the new government. "The great George Mason of Gunston Hall was chief author of the articles in this bill, which was to become the prototype for similar manifestos in other states as well as, eventually, for the Bill of Rights of the United States Constitution."7

The last of a sixteen-section "Declaration of Rights," adopted by the House of Burgesses on June 12, 1776, reflected the thoughts of Jefferson, and its final draft carried the influence of Madison's thinking as well. It declared: "That religion, or the duty which we owe to our Creator, and the manner of discharging it, can be directed only by reason and conviction, not by force or violence; and therefore all men are equally entitled to the free exercise of religion, according to the dictates of conscience."8

Patrick Henry penned the original draft of this article, which included a reference to "the fullest toleration in the exercise of religion." Madison was committed to nothing short of "free exercise" and succeeded in having "toleration" dropped from the final draft. He reasoned that a state which could "tolerate" could also prohibit.

[26] The Anglican Church still remained the established religion of the Virginia colony. Government salaries for Anglican ministers had been suspended. . . . [But] it was impossible to be legally married . . . unless the ceremony was performed by an Anglican clergyman, and heresy against the Christian faith was still a crime."9

Presbyterians pushed for abolition of the establishment. In October, 1776, just after the Declaration of Independence had been signed, the Presbytery of Hanover presented a memorial to Virginia's General Assembly asking for the removal of "Every species of religious as well as civil bondage," and noting that every argument for civil liberty gains additional strength when applied in the concerns of religion." Then they added this statement:

We ask no ecclesiastical establishment for ourselves, neither can we approve of them and grant it to others. . . . We are induced earnestly to entreat that all laws now in force in this commonwealth which countenance religious domination may be speedily repealed, - that all of every religious sect may be protected in the full exercise of their several modes of worship, and exempted from all taxes for the support of any church whatsoever, further than what may be agreeable to their own private choice or voluntary obligation.10

When Patrick Henry championed a general tax labeled "A Bill Establishing a Provision for Teachers of the Christian Faith" in 1784, Madison denounced it as "chiefly obnoxious on account of its dishonorable principle and dangerous tendency."11 Madison opposed any concept which gave Christianity a legal preference over other religious persuasions and which was in any way short of absolute separation of church and state.

In response to a suggestion from George and Wilson Cary Nicholas, members of the General Assembly, Madison took his pen in hand to arouse a public which already had freedom on its mind.

[27] In "A Memorial and Remonstrance," which was printed and circulated for signatures in 1785, he warned, "It is proper to take alarm at the first experiment on our liberties." He cited the free men all over America who refused to wait until usurped power had strengthened itself through exercise. Then he applied this logic to the religious freedom issue at hand, asking:

"Who does not see that the same authority which can establish Christianity, in exclusion of all other Religions, may establish with the same ease any particular sect of Christians, in exclusion of all other sects? That the same authority which can force a citizen to contribute three pence only of his property for the support of any one establishment, may force him to conform to any other establishment in all cases whatsoever?"12

The impact of Madison's precise logic created a public reaction so intense that proponents of the "Provision for Teachers of the Christian Religion" measure conceded defeat. The memorial had been signed by several different religious sects, even including a considerable number of the old hierarchy.

Madison seized this moment to push for the adoption of an "Act for Establishing Religious Freedom," written by Jefferson in 1779 but shelved at that time for lack of support. So prized was the content of this document that Jefferson chose it, coupled with his authorship of the Declaration of Independence and his founding of the University of Virginia, as the outstanding achievements of his life which were to be carved on his tombstone.

But the mood of 1785 contrasted with the mood of 1774. Seasoned by a hard-fought and costly conflict with Great Britain, political reformers were prepared to make religious liberty as absolute as the desired political freedom which the people sought. The act was passed by the Assembly in December of 1785:

[28] No man shall be compelled to frequent or support any religious worship, place, or ministry whatsoever, nor shall be enforced, restrained, molested, or burthened in his body or goods, nor shall otherwise suffer on account of his religious opinions or belief; but that all men shall be free to profess and by argument to maintain their opinions in matters of religion, and that the same shall in nowise diminish, enlarge, or affect their civil capacities. 13

[29]

Church-state separation had achieved legal status in Virginia! The Virginia

act of disestablishment was published widely, even in foreign countries. But

when Jefferson urged New England political leaders to move for disestablishment

in their colonies, he received little encouragement. John Adams reported the

mood of some: "I knew they might as well turn the heavenly bodies out of their

annual and diurnal courses, as the people of Massachusetts at the present day

from their meetinghouse and Sunday laws."14

[29]

Church-state separation had achieved legal status in Virginia! The Virginia

act of disestablishment was published widely, even in foreign countries. But

when Jefferson urged New England political leaders to move for disestablishment

in their colonies, he received little encouragement. John Adams reported the

mood of some: "I knew they might as well turn the heavenly bodies out of their

annual and diurnal courses, as the people of Massachusetts at the present day

from their meetinghouse and Sunday laws."14

The time was ripe for Federal intervention. Men of philosophical orientation like Jefferson sensed that this was the moment to establish "every essential right." The voice from Monticello cautioned:

"The spirit of the times may alter, will alter. Our rulers will become corrupt, our people careless. A single zealot may commence persecution, and better men be his victims. It can never be too often repeated, that the time for fixing every essential right on a legal basis is while our rulers are honest, and ourselves united. From the conclusion of this war we shall be going downhill. It will not then be necessary to resort every moment to the people for support. They will be forgotten, therefore, and their rights disregarded. They will forget themselves, but in the sole faculty of making money, and will never think of uniting to effect a due respect for their rights. The shackles, therefore, which shall not be knocked off at the conclusion of this war, will remain on us long, will be made heavier

When the Federal Constitutional Convention adjourned on September 17, 1787, it had produced an impressive document. It guaranteed that there would be no religious test for holding public office in the new government. But the Constitution had no bill of rights and no positive guarantees of church-state separation. George Mason was so distraught at this shortcoming that he refused to sign or approve the work of the convention.

[30] When Jefferson saw the final draft, he, too, was disappointed at the lack of major religious freedom guarantees; but he found it otherwise acceptable and stated a willingness to trust to the "good sense and honest intentions of our citizens"16 to obtain the desired amendments.

No sooner had local states initiated ratification procedures for the Constitution than the move for a bill of rights was launched. Virginia, New York, and New Hampshire asked for a declaration of religious liberty. As might be expected, James Madison was in the eye of the storm.

It was Madison who presented a long list of amendments to the First Congress, meeting in 1789. At the top of the list was a religious liberty amendment drawn by Madison himself. His colleagues subjected it to some reworking, but it was one of seventeen proposals sent to the Senate. Twelve amendments were finally sent to the states and ten ultimately ratified.

When the "Bill of Rights" was born in 1791, the wall of separation between church and state became the law of the United States of America. "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof."

Meanwhile the battle for disestablislunent in the new state governments got under way. Influential Virginia had pioneered the way. But "in the first [state] constitutions during the war period, only two of the thirteen new states, Rhode Island and Virginia, had complete religious freedom and separation. Six required Protestantism, two the Christian religion, and five a nominal establishment; and seven retained other provisions concerning such points as the Bible, the Trinity, and belief in heaven and hell. By the end of the Revolution nearly all the states had accepted the principle of separation of church and state."17

Not until 1833 did Massachusetts abolish some of the last significant remnants of religious establishment - and this state was the last of the original thirteen states to surrender the formal traditions of pseudotheocracy.

[31] Even then, disestablishment was not complete. One symbol of religious establishment, the Sunday blue law, remained on the books of most states. In 1804 Thomas Paine voiced a bemused amazement at the patent incongruity of this traditional symbol:

"The word Sabbath means REST; that is, cessation from labor, but the stupid Blue Laws of Connecticut make a labor of rest, for they oblige a person to sit still from sunrise to sunset on a Sabbath-day, which is hard work. Fanaticism made those laws, and hypocrisy pretends to reverence them, for where such laws prevail hypocrisy will prevail also."

One of those laws says, "No person shall run on a Sabbath-day, nor walk in his garden, nor elsewhere; but reverently to and from meeting." These fanatical hypocrites forget that God dwells not in temples made with hands, and that the earth is full of His glory. 18

View a PDF version of this chapter

REFERENCES

|

1. |

Reynolds v. United States, 98 U.S. 145 (1878). |

|

|

2. |

United States Statutes at Large, Vol. 8, p. 155. |

|

|

3. |

American State Papers and Related Documents (Washington, D.C.: Review and Herald Publishing Association, 1949), pages 91, 92. |

|

|

4. |

Charles J. Bochman, "Where Sabbathkeeping Began in North America,"Review and Herald, Vol. 140 (1963), No. 22, p. 6. | |

|

5. |

E. M. Halliday, "Nature's God and the Founding Fathers," American Heritage, Vol. 14 (1963), No. 6, p. 5. Used by permission. |

|

|

6. |

Ibid., p. 7. |

|

|

7. |

Ibid., p. 100. |

|

|

8. |

American Archives, Fourth Series, Vol. 6, pp. 1561, 1562. In American State Papers, Third Revised Edition (Washington, D.C.: Review and Herald Publishing Association, 1943), page 63. |

|

|

9. |

Halliday, Op. cit., p. 101. |

|

|

10. |

"Dissenters Petition, 1776," from Bishop Meade, Old Churches, Ministers, and Families of Yirginia, Vol. 2, Appendix, pp. 440-443. In American State Papers, pages 73, 74. |

|

|

11. |

Writings of James Madison, Vol. 1, pp. 130, 131. In American State Papers, page 99. |

|

|

12. |

Ibid., pp. 84, 85. |

|

|

13. |

Writings of Thomas Jefferson. In Norman Cousins, In God We Trust (NewYork: Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1958), pages 126, 127. | |

|

14. |

"Diary of John Adams." In American State Papers, page 101. |

|

15. |

Thomas Jefferson, Notes on Yirginia, Query XVII. In American State Papers, page 101. |

|

16. |

Reynolds v. United States 98 U.S. 145 (1878). |

|

17. |

American State Papers and Related Documents (1949 edition), page 92. |

|

18. |

Thomas Paine, Prospect Papers, 1804. In In God We Trust, page 432. |

oooOooo

View a PDF version of this chapter

To Ancient SDA's ............ To "What's New?"