The

scheme may have looked ridiculous to some, but participants discovered a unique

thrill in blasting the ball over the heads of the fielders.

The

scheme may have looked ridiculous to some, but participants discovered a unique

thrill in blasting the ball over the heads of the fielders...To Ancient SDA's ............ To "What's New?"

Dateline Sunday U. S. A.

by

Warren L. Johns

Issued with the author's permission

[59]

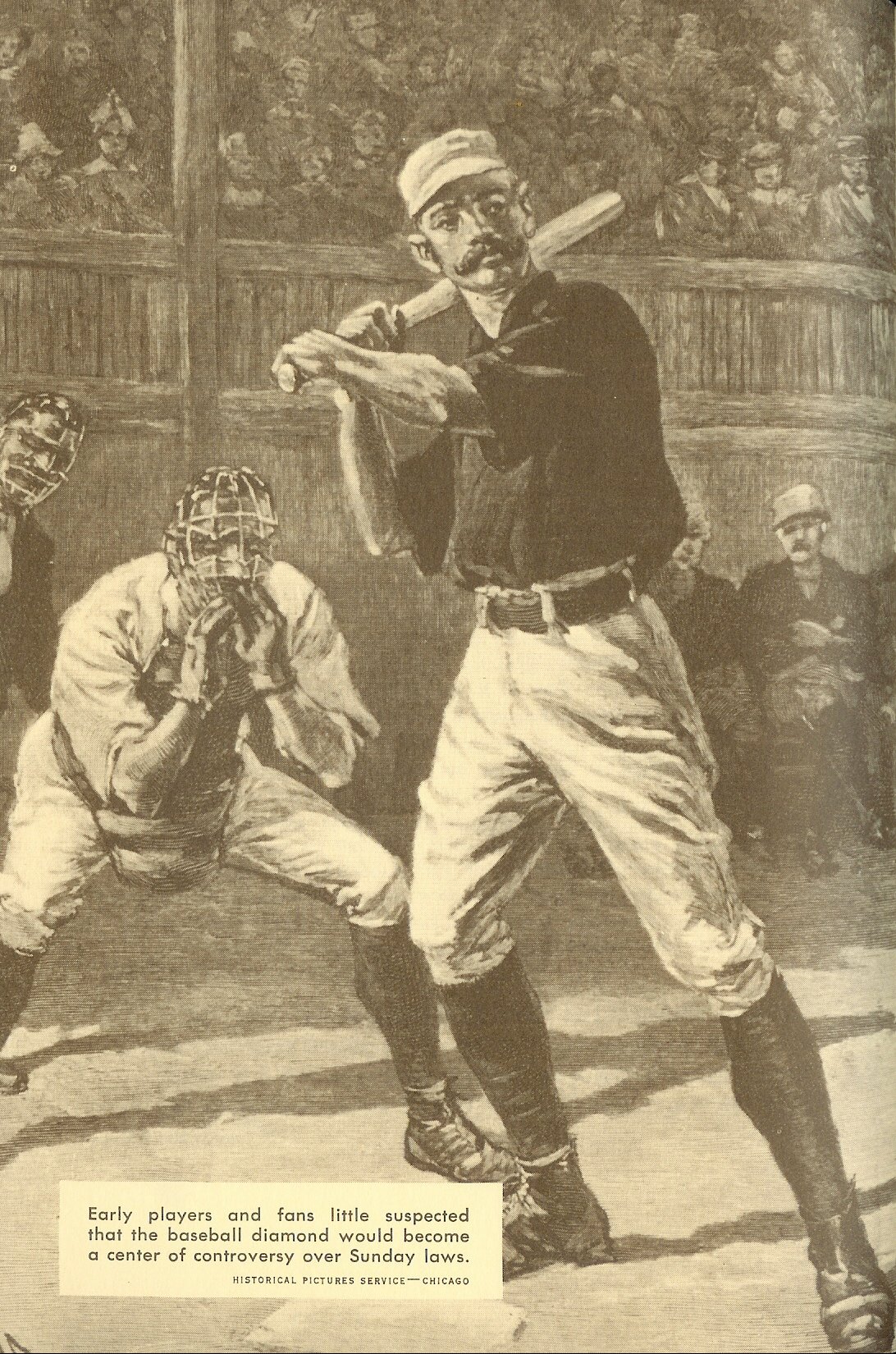

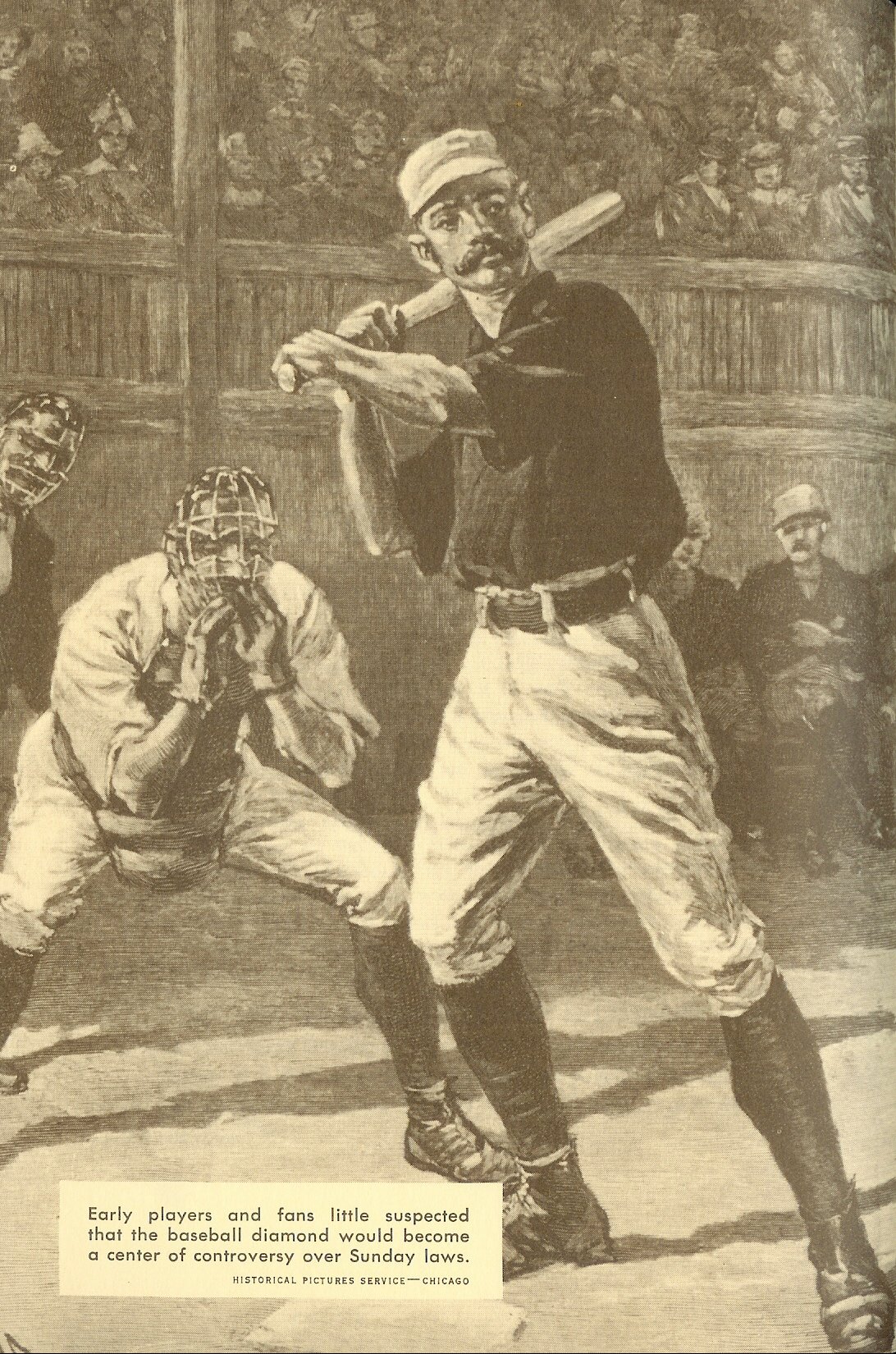

Chapter 6. PLAY BALL –

MAYBE!

Abner Doubleday, it is commonly believed, invented baseball.· He conceived what he thought to be a fun game, with players using a ball and a wooden club. The one with the ball threw it at the player with the club, who swung vigorously at the speeding missile. If he was lucky and hit the ball with the club, he could run around a 360-foot diamond back "home" to the point of his original departure. This success was termed a "run," and the team with the most runs won the game.

The

scheme may have looked ridiculous to some, but participants discovered a unique

thrill in blasting the ball over the heads of the fielders.

The

scheme may have looked ridiculous to some, but participants discovered a unique

thrill in blasting the ball over the heads of the fielders.

Baseball became a national pastime, played in the cow pasture, the comer lot, and the more sophisticated "diamond." Little did those early players suspect that electronic communications would one day create a multimillion audience for a single game, or that in Houston, Texas, one could lease a block of seats in the climate-controlled "Astrodome" for something like $18,000 a year. Nor did Doubleday dream of the antagonism or legal tests that would ensue as Sunday-law protagonists classified this form of recreation as "worldly amusement."

[60] Years ago on a Sunday "in Plainfield, New Jersey, . . . a large crowd assembled to witness a baseball game. Certain of the clergy had determined that no more Sunday baseball should be played in that place, and those in favor of the game also determined that they would defy the decision of the clergymen." "Play ball!" the umpire shouted.

The pitcher waited for the catcher's signal. The batter dusted his fingers and gripped his bat. Then the clergyman, accompanied by a deputy sheriff, entered.

"We have warrants for the arrest of anyone who participates in this game," announced the preacher. The deputy waved the legal papers. The clergyman and the ballplayers exchanged bits and pieces of rhubarb. But the crowd had come to see a ball game and began to hoot and holler. When this had no effect, they marched across the field and ousted the preacher and his deputy sheriff from the ball park. The deputy discreetly faded into the woodwork and allowed the crowd to chase the preacher, which they did, all the way to his house. The deputy persuaded the remaining spectators to depart the scene, and the game was called on account of Sunday laws!1

Characteristically, blue laws banned labor, business, and "worldly amusements."

In their laudable attempt to forsake worldliness and ritualism for the religion of the Bible, the Puritans committed the double error of applying the fourth commandment to the first day of the week and making the Mosaic legal code the basis for enforcement. In the Puritan colonies there arose the practice of applying to Sunday the sunset-to-sunset reckoning of the Biblical Sabbath, while the English law began Sunday at midnight.2

So severe was the Puritan attitude that religion appeared to offer more of a burden than a blessing. The devil received the credit for most of life's pleasures, while long faces were saved for the Lord. [61] If something was enjoyable, it was suspect as also sinful and "worldly." Effort was made to eliminate even the possibility of such pleasures and amusements in order to fashion a spirit of worshipful sobriety for the first day of the week.

Sixteenth-century golfers in Scotland ran afoul of blue laws. In Edinburgh, on October 1, 1593, "John Henrie, Pat Bogic and others were accusit of playing the Gowff on the Links of Leith during the time of the sermonnes, were ordainit to be put in prison until a fine of fourty shillings wer payit and cautioned not to do lyke again no type heirefter under the paine of punishment at the discretion of the magestrates.'3

Since statutory language in Scotland, the United States, or anywhere else, compels precision, Sunday-law proponents have compiled long lists of "worldly" pleasures to be prohibited on Sunday; and this theological programming has survived disestablishment. Organizations such as the "American Sabbath Union," a constituent of the "International Federation of Sunday Rest Associations of the United States and Canada," have helped perpetuate the pressure for the Puritan blue4aw morality.

In Alabama, in the 1930's and 1940's, it was a misdemeanor to play baseball "in any public place," though there was an exemption for cities with more than 15,000 population. In Connecticut, professional baseball was allowed, providing local legislative enactment also approved and the game took place "after 2 p.m." on Sunday. The law did not specify whether the crowd could come early and watch the players practice. In Florida, the team manager could be held guilty of the same misdemeanor as the baseball player. Idaho did not name baseball, but conceivably the prohibition of "noise, rout, or amusement" might cover ball playing unless it could be played in a quiet and dignified manner. In Indiana, you could play Abner Doubleday's game fearlessly, providing you were under fourteen years of age. If fourteen or older, you had to wait until after I p.m. and play at least 1,000 feet from "any established house of worship." [62]

(Picture moved) [63] Presumably the Pony League could play in the front yard of a church on Sunday morning without danger of prosecution. The Kansas code said playing a "game of any kind" on Sunday was a misdemeanor, but here the court came to the rescue and suggested that baseball was outside the scope of this statutory prohibition. Kentucky exempted "amateur sports" and "athletic games." Maine banned "any sport, game, or recreation"-subject to local government option.The sports-minded Maryland resident had to be particularly alert. A general prohibition prevented "gaming" or joining in any "unlawful pastime or recreation." If he lived in Hagerstown, baseball was allowed all day Sunday providing it was amateur. If commercial, baseball was permissible between the hours of 2 p.m. and 5 p.m. Montgomery County allowed "amateur" baseball and other "lawful" sport from 2 p.m. to 6 p.m.

Subject to local ordinance, "amateur" sports were lawful in some Massachusetts cities between 2 p.m. and 6 p.m., with "professional" sports allowed from 1: 50 to 6:30 p.m. In Massachusetts and Michigan, attending a prohibited event was considered as much a violation as participating. Mississippi said No to "ball playing of any kind." Missouri forbade "games of any kind," specifying a fine of $50. Nebraska gave cities the local option to "prohibit all public amusements, shows, exhibitions."

New Hampshire gave the green light to baseball if approved by the "selectmen of any town" and not played before 1 p.m. (( where admission is charged or donations accepted." New Jersey had a flat prohibition against "playing football" but ignored naming the national pastime except by inference under "any other kind of playing sports, pastimes, or diversions." New Mexico said No to any sports.

New York, with its "house that Ruth built,," declared it unlawful to play baseball" whether or not admission was charged, "but only after two o'clock in the afternoon." [64] North Dakota specified that Sunday baseball might not be played closer than 500 feet to a church or at any other time than between 1 and 6 p.m. Ohio forbade "sporting" to the fourteen-year-old and older, but since the next statutory words are "rioting" and "quarreling," it is questionable whether baseball was intended, if played with calm and decorum.

Pennsylvania required baseball to be played between 2 and 6 p.m., providing the voters of a municipality had given prior approval. South Carolina said No to "public sports" and named "football" specifically. Presumably baseball was included in other games, exercises, sports, or pastimes."

South Dakota not only named admission-charging baseball to the forbidden list but also implicated any citizen that advertised the game or made the ball park available. If a Texas ball park open on Sunday could be classed as a "place of public amusement," the owner exposed himself to fine. Utah exempted ball parks. And finally, Vermont, like many others, permitted baseball if it was approved by local voters and if the game "shall not commence until two o'clock in the afternoon."

The "worldly pleasure" aggregate list which became the subject of legislative dispute was not limited to the Doubleday phenomenon. And the corresponding list of rules and regulations shackling this awesome array of Sunday "pleasures" was no more likely to put the recreation-loving citizen's mind at ease.

Various state Sunday laws on the books or being contemplated in the 1930's and 1940's usually regulated, and often prohibited in varying degrees, the following items: shooting hunting, gaming, card playing, racing, football, tennis, golf: boxing, brag, bluff, poker, seven-up, three-up, twenty-one, vingtun, thirteen cards, odd trick, forty-five, whist, shooting for amusement, horse racing, tippling, theater performances, circuses, shows, basketball, hockey, skating, field contests, miniature golf, ski racing, ski jumping, bowling, billiards, rifle practice, motion pictures, dog racing, playhouse, merry-go-round, concert saloon, pool, wrestling, cockfighting, swimming, opera, lacrosse, soccer, auto racing, interludes, farces, plays, tricks, juggling, [64] sleight of hand, bearbaiting, bullfighting, fiddling, music for sake of merriment, fives, ninepins, long bullets, quoits, exercises or shows, tragedy, comedy, ballet, negro minstrelsy, sparring contests, trials of strength, acrobatic feats, club performances, rope dancing, street carnivals, polo, chasing game, gaming tables, and the carrying of an uncased gun in the woods.

The statutory language naturally creates interpretation problems for law-enforcement officials.

For example, the Ohio Sunday law permits trapshooting on Sunday afternoon "under the auspices of a recognized hunt, trapshooting, rifle or game club of this state"; but it warns, "Whoever, in the open air on Sunday, has implements for hunting or shooting with intention to use them for that purpose, shall be fined."4 The gun bearer could present a rousing defense on the "intention" issue.

Then there is the innholder of Maine faced with the threat of punishment for the "crimes" of his guests who spend Sunday "drinking or spending their time idly, at play, or doing any secular business"5 What is the innkeeper to do if he observes two guests playing a game of chess in the lounge? To act is to risk loss of business; not to act is to risk infraction of the law.

Georgia police officials face an unusual enforcement dilemma because of the statute which makes it a misdemeanor to "bathe in a stream or pond of water on the Sabbath day, in view of a road or passway leading to or from a house of religious worship."'

The recreations prohibited by these blue laws are not necessarily wrong or immoral in themselves, although some of them do run counter to prevailing religious mores. The majority of the statutes still bear the stamp of religious establishment.

Statutory expressions still on the lawbooks in the thirties and forties were reminiscent of Cotton Mather and associates. Arkansas talked of "Sabbath breaking" and "Christian Sabbath"; Colorado, "Sabbath day"; Delaware, "worldly activity"; Florida, 1( proper observance of Sunday"; Maryland, "Sabbath day"; Massachusetts, [65] "Lord's day" and "secular business"; Michigan, "secular business"; Minnesota, "breaks the Sabbath"; New York, "Sabbath breaking"; North Carolina, "Lord's day"; North Dakota, "Sabbath breaking"; Oklahoma, "Sabbath breaking"; Pennsylvania, "worldly employment"; Rhode Island, "breakers of the Sabbath"; South Carolina, "Sabbath day" and "worldly labor"; South Dakota, "Sabbath breaking" and "worldly uses"; Tennessee, "work on the Sabbath"; Vermont, "secular business", Washington, "observance of the Sabbath"; West Virginia, "on a Sabbath day"; and Wyoming, "desecration of the Sabbath day." But in seeking to establish a government-sponsored religious observance, the "Sabbath" Unionists still largely failed to gain the sympathy of the public. A case in point was the reaction of a Catholic minority in Kansas. The Catholics appreciated the relative freedom of the "Continental Sunday," which contrasted sharply with Puritan restraints. Editors of the Catholic Advance commented tartly in 1910 on the observation of a Methodist bishop that Kansas was "the greatest Methodist state in the Union." It was acknowledged that since "the preachers of that denomination seem to have things their own way in Kansas . . . the only thing the few other people who don't ride in Wesley's boat can do is to watch and pray."

The Advance had more to say:

We will let them preach the prohibition law until they pound their pulpits to pieces, . . . but we are strenuously opposed to any legislations that will deprive our young people of health-giving outdoor sport on Sunday afternoon. The Sunday is a day of rest from servile work but is not a day of inactivity or laziness. The Catholic Church established the Sunday anyhow and ought to know best how it is to be observed. She demands, under pain of sin, that all her faithful be present at the holy sacrifice of the mass on Sundays and hear the word of God preached from the pulpits. She requires some considerable time for prayer. This obligation being satisfied, she does not prohibit or interfere in [66] any way with those innocent amusements which serve for rest or recreation on any day. If our Methodist brethren choose to make laws for a more restricted observance of the Sunday among their own people, that is certainly within their right, and it is no business of ours; but when the same Methodist brethren put their heads together and decide as a church that they will have the State enforce their own church laws upon other churches who do not believe with them, then this is time to call a halt. If they will have the State legislature to enact laws forbidding Methodist children from playing baseball on Sunday afternoon, well, if they haven't religious spunk enough to keep them in the beaten Wesleyan track, we have no objection if they call in the policeman, but we won't allow them to send a policeman over to us, as we get along beautifully without.7

In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries there had been little to discourage Sunday-law promoters. Colonial blue laws had survived disestablishment in the states. Religious observance objectives had been perpetuated in statutory language. Minorities bad felt the sting of arbitrary and discriminatory enforcement.

Late in the nineteenth century the Sunday-law advocates felt strong enough to move on to even bigger things. Despite the language of the first amendment of the Federal Constitution, highly organized religious interests renewed their efforts to secure a national Sunday law.

View a PDF version of this chapter

REFERENCES

1. See "Sunday Baseball Games in New Jersey," Signs of the Times, Vol. 39 (1912), No. 21, pp. 11, 12.

2. American State Papers and Related Documents (Washington, D.C.: Review and Herald Publishing Association, 1949), page 85.

3. "The Sabbath Breakers," Liberty, Vol. 58 (1963), No. 1, p. 36.

4. Throckmorton's Ohio Code, annotated 1940, Baldwin's Certified Revision, Section 13053. In American State Papers, Third Revised Edition (Washington, D.C.: Review and Herald Publishing Association, 1943), page 492.

5. Revised Statutes of the State of Maine, Chapter 255, Section 40. In American State Papers, page 467.

6. Code of Georgia, Annotated 1936, Section 26-6910.

7. "Church and State," Catholic Advance, November 5, 1910. In American State Papers, pages 585, 586.

[67]

oooOooo

View a PDF version of this chapter

To Ancient SDA's ............ To "What's New?"