October

3, 1965, was a typical Sunday in Southern California.

October

3, 1965, was a typical Sunday in Southern California...To Ancient SDA's ............ To "What's New?"

Dateline Sunday U. S. A.

by

Warren L. Johns

Issued with the author's permission

[215]

Chapter 18. FREEDOM

TAKES

A HOLIDAY

October

3, 1965, was a typical Sunday in Southern California.

October

3, 1965, was a typical Sunday in Southern California.

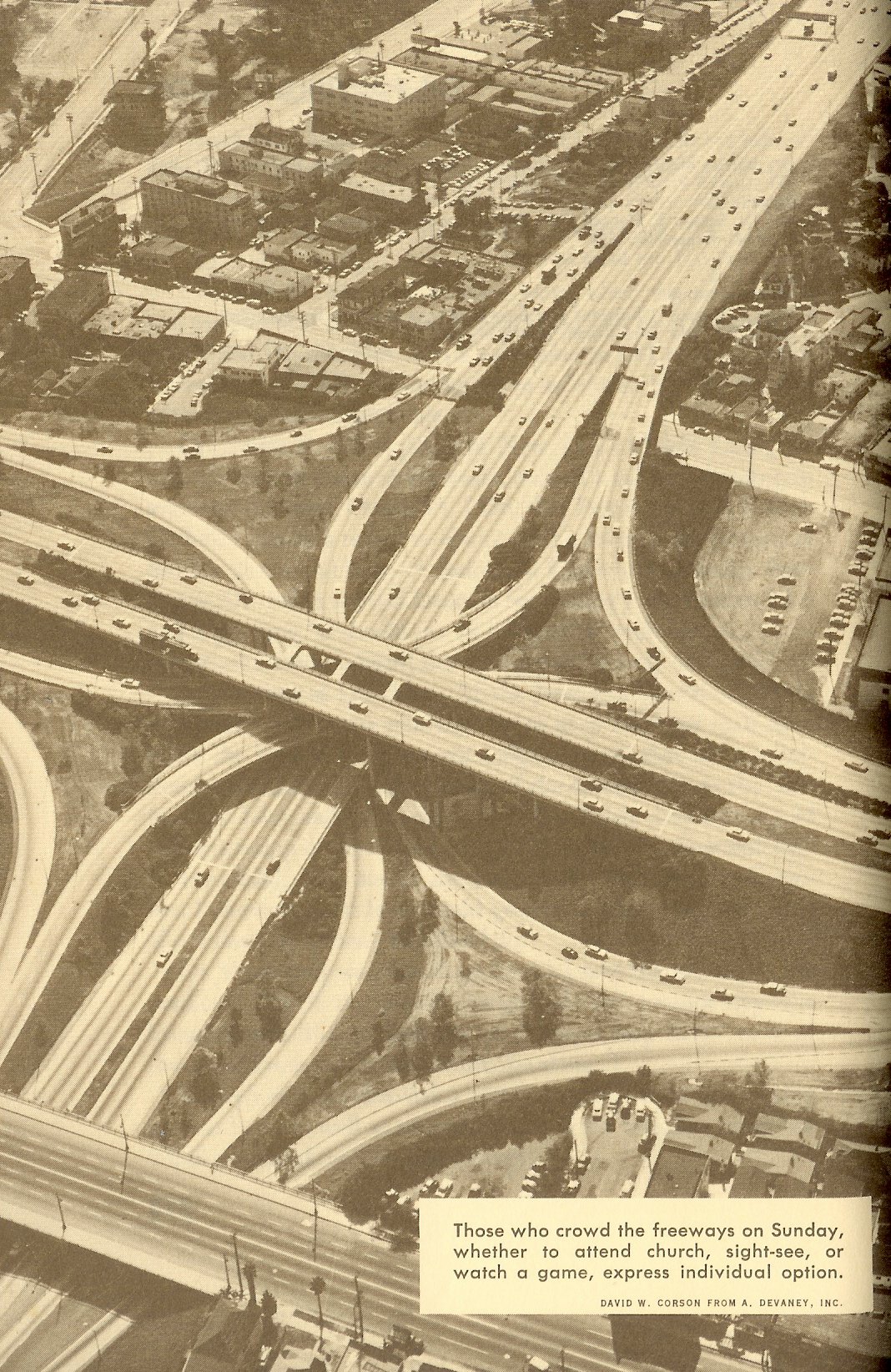

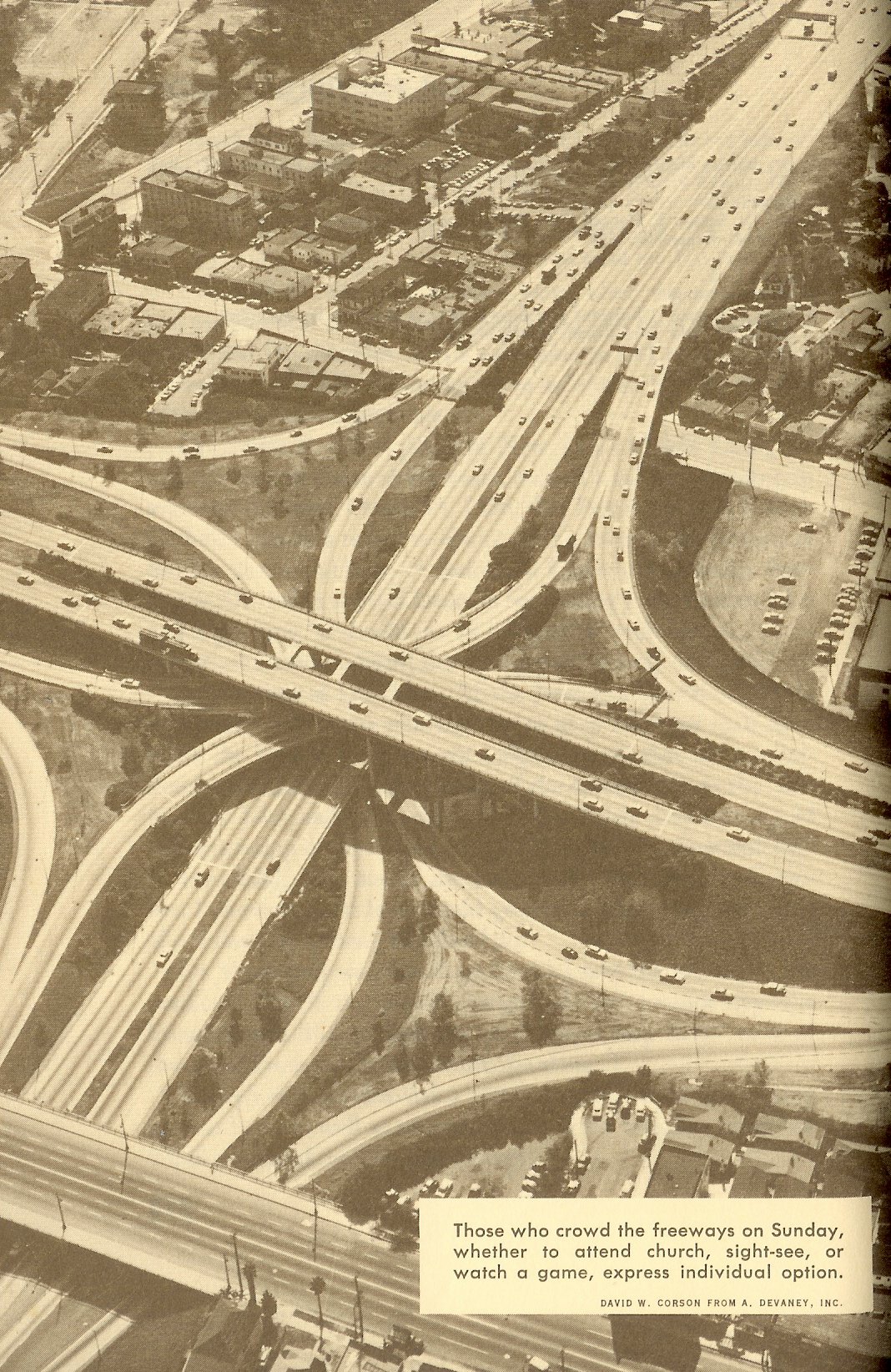

The San Bernardino freeway bulged with the vehicles of last-minute visitors to the Pomona Fair. The Dodgers played the last baseball game of the regular season, relishing a newly won National League pennant victory. The Los Angeles Rams and their football cousins, the Minnesota Vikings, trampled each other into the Coliseum turf. Disneyland, Knott's Berry Farm, Marineland, and Sea World beckoned to year-round adventurers. Sailboats caught the breezes at Balboa Bay and Lake Arrowhead. The "lively ones" rode the surf at San Clemente while stay-at-homes puttered in yards to please green-thumbed spouses. Early in the day, many Californians attended a church of their choice. Others had flown to New York to greet the precedent-shattering visit of Pope Paul VI.

Each of the reactions was an expression of individual option. There was no threat of fine or arrest for violating a blue-law code. Californians enjoyed an "atmosphere of recreation," do-it-yourself style, in contrast to the rigid blue-law language approved by the United States Supreme Court in 1961.

[216] Amazingly, the California public seemed to relish a weekend with the family, blissfully unaware that this atmosphere of happiness and free expression belonged to them without the aid of police official grasping their collars and warning "have fun, make for rest, relaxation, repose, and recreation as you are ordered, or face fine and arrest!"

No one had to use a stopwatch to make sure the ball game started at a "noncriminal" hour. And fortunately no one had argue with the supermarket cashier that a balloon could be classed as a "novelty" and sold legitimately, rather than as a "toy which might make its Sunday sale nonessential and "criminal".

Californians had done without a general Sunday-closing law since 1883 and they had done very well, thank you. The state enjoyed a golden age of prosperity and growth, and the lack of blue-law "protection" did not stem the tide of immigrants who swept over the high Sierras, bringing newcomers to California at a rate confounding census takers.

The only thing to spoil California's "atmosphere of recreation" was an occasional invasion of smog. But freedom takes a holiday when the blue hue of coerced Sunday observance spatters the scene with arbitrary blots. It would take a lot of fast talking to convince the open-space-minded Westerner that enforced Sunday observance could offer him anything except a pain in the neck and the pocketbook. What, then, is the secret that makes the possibility of being "criminal-for-a-day" so tremendously attractive to some modern Americans?

The traditional blue-law attack has been aimed at three "evils" which supposedly inhibit the proper observance of Sunday: worldly amusements, Sunday labor, and Sunday commerce. Originally these "evils" were assaulted in order to foster religious practice and perpetuate a theological tradition. Now that the religious orientation of the blue law can be spurned, a la public welfare, what is the legitimate secular purpose that nourishes its future?

A very nebulous one, carefully camouflaged by prolific verbiage! [217] Far from contributing to a carefree "atmosphere of recreation," Sunday laws actually curtail amusements and legitimate recreation, exposing the seeker of first-day pleasure to criminal sanctions. Free Americans can do without this form of paternalistic nonsense. Usually if given the opportunity to choose their own Sunday observance, they would say, "Please, I'd rather do it myself."

As to the labor issue, Sunday-observance laws offer no protection to an employee working in a Sunday "essential" activity. Under the typical scheme, the citizen is free to work Monday through Saturday in a "nonessential" job. Then he can punch a Sunday time clock within the "essential" labor category. Where is the protection for labor or the individual? It has to come from the legitimate health and welfare measures which provide minimum wages, maximum hours, and the "one-day-in-seven" statute, guaranteeing at least one full day's rest in each consecutive seven-day period. Also, labor organizations negotiate agreements designed to provide labor with a fair share of the nation's wealth and leisure. A blue law is a week-kneed substitute for genuine labor-oriented legislation.

Finally, the arbitrary restraint on commerce and competition demanded by Sunday-observance laws mocks free enterprise. In a totalitarian state the arbitrary selection of acceptable versus criminal classes of commerce one day each week might be compatible with philosophies which uphold confiscation of property. But in a free competitive system? Is there any reasonable justification for a system which proposes to approve the sale of film but ban the sale of a camera on Sunday?

The recently revitalized secular-purpose arguments of Stephen Johnson Field can hardly stand on their own two, or three, feet. And with these three undergirding secular-purpose objectives of blue laws tattered and torn, what argument is left to urge coerced Sunday observance in the space age?

Nothing except simple, old-time religious interest! It existed both before and after 1961. [218] Without the sustaining support of religious pressures, the entire blue-law scheme enmeshed in state lawbooks would collapse overnight. It would take some monumental haystack searching to find even one needle of secular concern that could make the public want the continued "benefits" of a "criminal-for-a-day" environment.

On the other hand, the blue-law scheme is so problem-plagued today that "what's wrong" can be told in twenty-five reasons or less without resorting to ivory-tower hypotheses.

Public opinion is a good place to start.

Who wants blue laws anyway? Certainly not religious minorities who worship on the seventh or some other day. It is highly unlikely that the non-Christian relishes the prospect of a fine for enjoying worldly pleasure on Sunday. Even a large number of Christians who attend church on Sunday have attacked blue laws with surprising vigor.

Said a Lord's Day Alliance speaker from Boston: "Legislation is not the answer, and we have found that out many times here in this land of ours. You simply cannot legislate morals, you cannot legislate good behavior, you cannot legislate the observance of the Lord's Day."1

The Baptist New Mexican questioned the fairness of requiring seventh-day observers to close businesses on Sunday and deplored "the fact that Houston ministerial groups asked for boycotts against businesses which remain open on Sunday."2

Two Lutheran clergymen from Milwaukee took issue with other area ministers seeking to force Sunday store closing. They appealed for a program which would allow employees to worship on Sunday if they desired and "asked churchmen who desire to legislate the Sabbath principles of rest and worship to consider [that] . . . the Christian church must not lean upon laws imposed upon those outside the church to secure Sabbath observance among her own people."3

[219] Gilbert S. Fell, minister of Central Methodist Church in Atlantic City, noted shortly before the landmark 1961 Supreme Court opinions that "whatever the cause perhaps the so-called religious revival of the 1950's there is increasing agitation for more stringent Sabbath observance laws." While affirming his personal belief in the great religious value of a weekly holy day, he went on record as vigorously opposing "the recent attempts to reimpose Sabbath laws." He cited several reasons for his opinion:

First, these laws run counter to the First Amendment. . . Since I would not wish to be made to observe Saturday as the Sabbath, I do not see how I can enforce other groups to observe my wish. . . .

Second, to call such laws "health measures" is a sham and a fiction. Perhaps at their inception these laws were to some degree intended as health measures although this interpretation is questionable but surely in these days we have ample leisure time, so much so that the sociologists see its amplitude as a problem.

Third, these laws violate the Protestant affirmation of personal free choice. Let those who wish the Sabbath observe the Sabbath.

Fourth, the Sunday laws tend to be discriminatory. In New Jersey it seems likely that a law will pass permitting a man to go out and drink himself under the table on Sunday but preventing him from purchasing a bathing cap or a toothpick on that day.4

Shortly after the 1961 Supreme Court decisions, the 174th General Assembly of the United Presbyterian Church in the United States heard a report from its Special Committee on Church and State. The report recommended that "this General Assembly affirms its conviction that the church itself bears sole and vital responsibility for securing from its members a voluntary observance of the Lord's Day. The church should not seek, or even appear to seek, the coercive power of the state in order to facilitate Christians' observance of the Lord's Day." [220] Though not demanding repeal, the recommendation urged Presbyterians not to support new Sunday laws, and to seek exemptions for seventh-day keepers under existing laws. The essence of this document was adopted by the General Assembly of the church meeting in Des Moines, Iowa, in the summer of 1963.

Allan C. Parker, Jr., pastor of the South Park Presbyterian church, Seattle, Washington, made a strong appeal: "I do not believe that because I have set aside Sunday as a holy day I have the right to force all men to set aside the day also. Why should my faith be favored by the state over any other man's faith."6

Princeton Theological Seminary President James McCord, a leader in the ecumenical movement within Episcopal, Methodist, Presbyterian, and United Church of Christ congregations, sees blue laws as a part of the Puritan tradition handicap burdening the church today. "The church is still chock full of symbols about wildwood and Puritan America. It is amazing to me that New England has imposed itself on all America. It has, become the stereotype for a religion with all the juice squeezed out of it." He decried the "blue laws and blue noses"7 that had emerged.

Roman Catholic voices have also been heard. "Father Robert F. Dinan of Brighton, Massachusetts, dean of the Boston College School of Law, said 'the religious freedom of non-Sunday observers had been and is clearly infringed upon by the law's establishment of Sunday as the universal day of rest." A Georgetown University law professor, Dr. Chester J. Antieau, "said Sunday closing laws 'unquestionably do grave economic injury' to some religious minorities. He also challenged the validity of the argument that Sunday laws 'keep our families together.' He added that 'greater ease of police enforcement is hardly a justification' for Sunday laws. 'There is not one whit of evidence that it is impossible or even difficult to enforce the rest laws in any of the twenty-one states that exempt some minorities from Sunday controls."' [221] And "Father Charles E. Curram, of Rochester, New York, professor of moral theology at St. Bernard's Seminary, doubted that solutions lay in the enactment of more precise laws. He described as 'a fallacy' the general impression that law and legislation 'make Christianity."8

The public at large has registered some forceful reaction to Sunday laws at the polls. In a formal election the citizens of Toronto, Canada, made their thinking clear. On December 5, 1960, they found an occasion to be heard.

Sunday movies and sports received strong support at the polls in the Ontario municipal elections despite the pleadings of Protestant and Roman Catholic church leaders. Here in Toronto, the Sunday movie vote ended in a lopsided score 81,821 for and 45,399 against. Meanwhile, the Toronto suburbs of North York and Scarborough voted two to one in favor of Sunday sports. In nearly all other areas where the two issues were on the ballot the voters approved.9

When Michigan tried a Sunday-closing law with a Saturday-closing option after the Supreme Court had spoken in 1961, only three of the eighty-three counties in the state implemented its provisions.

The people of a free country also vote with their feet. If they don't wish to go somewhere or do something, they won't be forced. If Americans didn't want to shop, stores couldn't afford to remain open on Sunday. Why not let citizens decide for themselves? If the majority of the people are against it, Sunday commerce will simply fade away. If the people want to shop on Sunday, why curtail free expression? A man shouldn't be forced to work on Sunday if he chooses to worship on that day. But why tell him how to spend his leisure?

With little evidence of popular public support, Sunday-law backers in the space age look to commercial interests for underwriting and religious interests for leadership. But Mr. Average Citizen stays rather consistently off the blue-law bandwagon.

[222] When Maine Governor John H. Reed OK'd a 1965 bill allowing Sunday sales of liquor in his state, he explained "It is the will of a majority of the people of this state for this act to become law." Despite the protests of a Christian Civic League, which vowed to force a statewide referendum on the issue, the governor explained a reversal of his previous "matter of conscience" opposition as due to the fact that citizens have had "ample opportunity to make their views known to their elected representatives." 10

Arbitrary classifications. In 1956, then Governor Adlai L. Stevenson of Illinois vetoed a bill that would have sent a citizen to jail for ninety days for selling an auto on Sunday. Asked the, governor, "If such a restriction on Sunday trade is sound for automobiles, why should it not be extended to newspapers, groceries, ice-cream cones, and other harmless commercial transactions? Carried to its logical extreme, any business group with sufficient influence in the legislature can dictate the hours of business of its competitors. And if hours, why not prices?"11

Once committed to the Sunday-closing principle, reason takes a back seat to pressures and special interests. Where can a legislature safely draw the line on Sunday conduct without facing the twin charges of "arbitrary" and "unreasonable"?

Here's an example: Under some blue laws it's a crime to sell a shirt. It follows that it should then be unlawful to clean or launder a shirt on Sunday at least for pay. Then, how about coin-operated laundromats? The Canadian Supreme Court answered this in 1961 by saying that an automatic coin laundry infringed the "Lord's Day Act" despite the fact no one was actually employed on the premises.12

Once you forbid coin laundromats, to be consistent you must extend the ban to coin-operated candy and soft-drink machines, and from there to coin-operated telephones. After banning a coin telephone, the telephone lines should be shut off to private phones as well, because this use involves only a different method of payment.

Where can the legislature draw a consistent line?

[223] When a crackdown was attempted on blue-law violators in Cincinnati, Judge Clarence Denning refused to call it a crime to wash a car when service stations could legally wash a windshield. Asked the judge, "How far does the person using a sponge to clean an auto have to propel said sponge before it can be said he is in violation of the law? And conversely, where shall he stop in the cleaning of an auto to be within the purview of the law?"13

The perplexing problem of arbitrary, irrational, and vague classifications reached hilarious heights in Michigan shortly after the Supreme Court spoke in 1961. Attempting to build on the shaky "secular" premise, the Michigan legislature devised a two-headed beast which forbade certain conduct on Sunday or Saturday, depending on the day of rest selected. The bill tickled the funnybone of Michigan newspapers like the Jackson Citizen Patriot:

Let's assume that the Saturday or Sunday store-closing bill becomes law and the state hires 23,789 special policemen to enforce it and arrest all violators. Among the typical lawbreakers could be a solid citizen who bought a hammer on Sunday for "emergency provision" but was caught using it to make a birdhouse. There will also be the felon who purchased a lawn chair "for exclusive outdoor use" and was nabbed red-handed with it in his living room, being used as an extra chair for a poker party. And consider the sad case of the housewife who bought a pillow, claiming it was for "outdoor camping use," but was apprehended by a special policeman while testing it indoors.

And the court dockets will be jammed with such cases as the fellow who bought a hat to go with his legally-purchased raincoat, the defendant who added a camera to his film and flash-bulb purchase, and the accused who bought a radio tube and stuck it in a hi-fi amplifier.

[224] Legal questions will probably be raised, too, on such vague terms in the new law as "perishable fruits and vegetables," "power-operated grooming supplies," and "large and small appliances." For instance, consider the plight of the distraught judge who will have to rule on a plea of "unperishable fruits" or of the defendant who claims the appliance he bought on Sunday was neither large nor small but medium. Where will it all end?14

State Senator Carlton Morris of Kalamazoo challenged anyone to try to "figure out this hodgepodge." Said the senator, "I hope you're happy with this bill when we get through it. I gather, under it, you can buy a hot dog but not a bun. Its even laughable to try to explain it."15

The Saline Reporter placed a call for King Solomon in impassioned, tongue-in-cheek plea:

The dazzling inconsistency of Michigan's blue laws never fails to confound us. For years, we have had trouble explaining to out-of-state guests that they could drop the whole family budget at the race track if they chose but if they wanted to play euchre for ten cents a hand, we'd have to pull down the shades first. Now, if the proposed "Sunday closing" legislation passes and isn't vetoed by the governor, we're going to have to tell them they can't buy a screwdriver on Sunday in any store with more than 4,000 square feet of floor space . . . unless they want to drive down to Clinton County for it. It will be legal to buy aspirin on Sunday but purchase of toothpaste may turn out to be illegal and immoral. Question: Is tooth paste a drug?

You'll be able to buy outdoor furniture, but sale of indoor furniture would be forbidden. Apparently reverence comes easier outdoors. Bread, but not coffee. Butter, but not jam. Perishables are exempted. No kidding, all these fine distinctions have passed the House of Rep. by a whopping vote of 86 to 12. The "Sunday closing" law promoted by some retail and church groups, has been bitterly fought by most of the supermarkets . . . and by the tourist and sportsmen's groups, who won their point: It will still be legal to sell ammunition on Sunday.

The law, as written, will allow Saturday closing as an [225] alternate, for those who regularly observe the Sabbath on Saturday. Merchants may take their choice. The bill would apply only to the big-population counties, of 130,000 persons or more. So when we explain to visitors that they can buy camping equipment anywhere on Sunday, but it would be breaking the Sabbath to buy toys (in Washtenaw county, but not in Lenawee county) unless the store has less than 4,000 sq. ft. . . . may they be forgiven for thinking they're dealing with the White King?16

The Coldwater Daily Reporter couldn't resist some gentle needling of its own:

We see where the Michigan House of Rep. passed a Sunday-closing bill this week. It's all right to sell food to eat on the premises, but you can't take it home with you. If you want bedding such as blankets or pillows, you can't buy it unless it's for outdoor camping. Footwear and headwear are out except for rainwear and overshoes. So if you see a bareheaded man camping out in his overshoes next summer, better stop and feed him. 17

The Battle Creek Enquirer and News struck a more sober note by introducing the word "insanity" to explain the development of a "Frankensteinian monster":

We'll ruefully have to admit we gave the majority of Michigan's state representatives more credit for sound judgment than they deserved. In the house last Tuesday more than 80 of its 110 members again voted for that fantastic, utterly ridiculous creation known as a Sabbath-closing law. After undergoing the state senate's scrutiny, during which the bill was amended to the point of inanity or maybe we should mention (pardon, please) the word, insanity there seemed to be some hope that the House would then recognize the Frankensteinian monster it had put together. Most political observers confidently predicted demise of the bill, but they were so wrong. They and that includes this corner completely underestimated the temper of the legislators. [226] The house majority simply wanted a Sabbath-closing law, and they were going to have one, no matter what! And now that they've got it, what are they going to do with it, assuming that Gov. Swainson signs the measure? Even if the governor vetoes it, the legislature probably will override him (here we go predicting again) because the house surely wants the law. It's going to be fun watching the enforcement of this legislative creature. It's going to be quite entertaining to observe the way businesses will figure out tricks to outwit the law and its enforcers. And, we just can't wait for the first court case to learn how a judge is going to interpret some of the law's provisions. Best of all, we're going to enjoy the predicament of the ones who cooked up this mess of political pottage. They have succumbed to expediency without thought of the consequences. They can well be haunted by these words from Michigan's late Senator Arthur H. Vandenberg, "Expediency and justice frequently are not even on speaking terms."18

The governor did sign the bill, with some misgivings. But eighty of the eighty-three counties in the state took advantage of the local-option privilege and refused to implement its provisions. In 1964, all eight justices in Michigan's high tribunal lent a hand to give the modernized blue law the gate. One of three separate concurring opinions succinctly pinpointed the Achilles heel of the "secular" blue law: "When a law makes violation criminally punishable, it must be definite and certain enough so that violation thereof becomes ascertainable in some manner other than by extrasensory perception, moon gazing, or resort to a crystal ball."19

The arbitrary hodgepodge of post-1961 "secular" Sundayclosing laws raised the void-for-vagueness issue in a dramatic way and overlapped the potent enforcement problem.

Take a good look at the enforcement problem!

Police officers are overworked and underpaid. Epidemics of theft and criminal violence clog police blotters. Court calendars lag behind burgeoning civil and criminal case loads. [227] Fires of civil disobedience and chaos bordering on anarchy char the landscape and eat away established legal framework. The national crime rate skyrockets. Now dump the blue laws into the laps of the police and say, "Here's a 'criminal-for-a-day' list! Enforce it!" of course there will be the occasional prosecution and conviction. But realistic, uniform enforcement impossible! And without consistent enforcement, another breeding ground for contempt of law is set in motion.

Imagine you have been charged with policing the average blue law. Then you can imagine what the police are up against.

Sunday "crimes" are by their nature limited to a twenty-four hour period. In some cases arbitrary time slots within that period, such as after 2 p.m. and before 6 p.m., compound the confusion. The harassed enforcer had better be armed with a stopwatch. Next he has to check the geographic boundary. Is this a county which exercised its local option to operate outside some portion of the Sunday-law scheme? Or is this a city with a population level exempted by the legislature from the operation of the law? The police official had better have his map, his compass, and a recent census report.

But before he makes an arrest, he also should check through the forbidden list and cull out the "essential" from the "nonessential." Selling a car might be forbidden, but selling an auto accessory could be all right. A pair of tennis shoes would be a valid purchase as "sporting equipment" but might be banned if classed as "wearing apparel." The officer should have an up-to-date list in his pocket direct from the state legislature and be prepared to perform the functions of judge and jury to determine if a "crime" has actually been committed justifying an arrest.

No wonder the Cincinnati police took a good look at the enforcement mess late in 1964, and quit trying. No more whip cracking "against Sunday business operations unless the public itself files the complaints."20 [228] City Solicitor William McCain declared that the city lacked the police manpower for adequate enforcement. It was a travesty to arrest only a few when summonses could not, as a practical matter, be issued to all business-men breaking the blue law. It is also ridiculous to encourage Gestapo-style police state where neighbor becomes an informer against his "one-day-criminal" neighbor. Americans like to think that such a system went out of style with the disappearance of the little man with the big mustache. Neighbor versus neighbor court cases are not compatible with the "rest and relaxation" goals of Sunday proposals.

Some dilemma! Push for full enforcement and everyone becomes suspect. Ignore the law and help yourself to a breeding-ground for contempt of law and law-enforcement officials.

When a leading Maryland auto dealer promised not to sell any more cars on Sunday, the pending prosecution of a prior violation was pigeonholed. State Attorney Arthur A. Marshall, Jr., observed that blue laws "have been more of a detriment to the county than an aid," but since they were the law, there was no choice but "to enforce the laws whether I agree with them or not."21

Olmstead County District Judge Arnold Hatfield outlawed the Sunday-closing ordinance of Rochester, Minnesota, because it singled out business enterprises employing six or more persons.22 A Fort Wayne, Indiana, superior court judge took issue with a colleague's ruling in the Gary City court and ruled the Indiana blue law unconstitutional because it was not explicit enough and was discriminatory.23

In 1962 the North Carolina Supreme Court junked the oldtime blue law, and the legislature responded with a new and modem version in 1963. This also got the judicial ax in 1965 because it exempted forty-eight of the 100 counties in the state and legislated against the state constitution, prohibiting trade regulation by local or special legislative act.24

[229] An 1855 Kansas blue law was declared "so general, vague, and indefinite" that the state supreme court discarded it in 1962.25 Five days after the state legislature came back with another one in 1963, a district court judge enjoined its enforcement against supermarkets which would be closed on Sunday by legislation that allowed the small neighborhood grocer to stay open. 26

Although the 1855 Kansas blue law had been copied from the venerable 1821 Missouri model, the Missouri high tribunal resisted an attack on the Missouri Sunday law in a December, 1961, decision. But fifteen months later all seven justices of the Missouri high court joined in reversing the 1961 decision and threw out the old law because it was "so vague and indefinite" that it was "incapable of rational enforcement."27

This prompted a day of jubilee. A collective sigh of relief could be heard along the banks of Old Man River. A newspaper account described the scene in Kansas City.

Drugstore clerk Billie Canon sold a pink-and-yellow Easter bunny Sunday and she wasn't arrested. In the same store, a year ago, another clerk sold a similar bunny. She was arrested for breaking a 137-year-old law that said only items of necessity could be sold on Sunday. . . .

"People are coming in to shop and they don't have to ask, is it OK to get this," said Pete Reimer, basement manager at a store of the large Katz drug chain.

Under the blue law, you could buy French perfume at one counter, but not soap at another; no light bulbs, but charcoal briquets. Paper napkins and facial tissues were considered necessary, but paper towels were not.

On April 23 last year a desperate citizen paid for detergent and bleach at a Kansas City grocery store and made a clean getaway by pulling a pistol on two clerks. He phoned later to apologize: "I needed the soap to wash the baby's clothes."28

Although religious groups and other Sunday-law proponents still clamored for a new blue law, the "void-for-vagueness" point had been made. [230] Although there were other post-1961 decisions which sustained blue laws, the enforcement and arbitrary classification basis for rejection had received more than incidental recognition in state supreme courts.

Free enterprise also runs at cross purposes to blue laws. To use Sunday-observance laws as tools to regulate or curtail competition is to give the voice of free enterprise a hollow ring. Adlai Stevenson vetoed the 1956 Sunday-closing proposal for Illinois auto sales while he issued a clearcut pronouncement for free enterprise:

Under our free enterprise system, government should not interfere by regulatory or prohibitory laws in the business field except (1) where the activity in question is directly related to the public health, safety, morals, or welfare, or (2) to enforce competition. Traffic in automobiles does not qualify under the one, and, so far as the latter is concerned, its only purpose and effect are to restrain competition.29

Mayor James Baker of Pomona, California, used the same argument and put his political future on the line in the summer of 1961 when he opposed a Sunday-closing ordinance applicable to barbers. Despite the support given the measure by the city council, and in the face of pressures from local barbers, the Y.M.C.A., St. Joseph's Catholic Church, the First Baptist Church, and St. Paul's Episcopal Church, the indomitable mayor voted against the measure because he considered it an infringement of free enterprise. This, he said, would set a precedent in the city that could extend to other businesses. Although he lost the battle, the mayor made his point and quipped, "I've probably just made so many enemies among the barbers, I will have to go to Los Angeles for a haircut."30

The time-is-property concept of James Madison is compatible with the free enterprise system. Blue laws are inconsistent with the system and diametrically oppose the philosophy behind it. Businessmen have as logical a basis to contest the arbitrary confiscation of their time as any other portion of their property.

[231] Colonial blue laws flourished in a predominantly rural society with isolated communities and limited communications. Individual ownership of business and needs unique to small geographic areas dominated business practice. Sunday-observance laws fit this framework in an effort to regulate the mores of a community, and, depending upon its heritage, each localized religious establishment had its own moral flavor. Since then there have been a nineteenth-century industrial revolution and a twentieth-century technological evolution. The pastoral scene of provincial colonial society is no more. Families live in an urban sprawl which spawns cities that overlap into megalopolises. Communications have telescoped time. Corporate interaction has partially replaced individual proprietorship. Labor organizations with bargaining power have dominated creative workmanship. Call it the space age, the atomic age, or the computer age times have changed!

The dynamics of contemporary commerce transcend traditional boundaries of time, geography, language, and custom. The antiquated blue law is ill at ease in the modern environment. There is no horse and buggy to transport its tradition nor whipping post to support its enforcement. The law was implemented in a social-political context which no longer exists. And, unlike timeless principles of freedom, the blue law remnant was painful in the old days and is impractical in the new.

A weekly day of rest for the individual is needed today more than ever. But rather than futile efforts to force round pegs into square holes, the day and manner of rest should be guaranteed to individual choice, for individual need is the core of public health and welfare concern.

It is opportune to face the future with the emphasis on freedom. A future which can achieve the valid secular objectives supposedly achieved by Sunday laws can find alternative procedures compatible with freedom.

[232] A true holiday, like the Fourth of July, has no criminal penal ties. By contrast, blue laws make the workingman a criminal and a victim of the very law supposed to protect him! Unlike, true health and welfare measures which protect the individual from being forced to live under improper working conditions, Sunday laws expose the individual to penal sanctions. Sunday laws protect and honor the observance of a day. They do not protect the individual.

Sunday laws have consistently failed to shake their religious overtones. Their essentially sectarian and oppressive nature will not disappear with some kind of blue magic. Colonial Sunday-observance laws represented religious establishment and impaired the free exercise of religion. In the 1960's blue laws still rely on religious interests for support and survival.

The existence of a church in a free society, along with most of its traditions, inevitably produces beneficial secular by-products. But to claim that indirect secular purpose flowing from a religious observance justifies government establishment of an observance is to leave the door wide open to infringement and usurpation.

A tax-supported church and a "Sabbath" enforced by penal sanction were earmarks of colonial church-state union. Coerced Sunday observance, symbol of that union, violates the spirit of the First Amendment. Government funds appropriated to religiously sponsored and operated "secular" programs of health and education is the logical next step backward. Seizing the primacy of secular-purpose excuse, proponents of almost any religious program can argue vehemently for some form of government cooperation, approval, or financial sponsorship.

Unless the blot of blue-law establishment is erased from state statute books, the camel's nose of something less than absolute religious freedom will remain in democracy's tent. Blue laws have pierced the wall of separation, and the slightest touch can widen the breach.

View a PDF version of this chapter

[233]

REFERENCES

|

1. |

C. Gordon Brownsville (Senior Minister of the famous Fremont Temple Baptist Church, Boston, Massachusetts), in Lord's Day Leader, First Quarter, 1964. |

|

2. |

Religious News Service, January 17, 1961 |

|

3. |

Ibid November 16, 1960. |

|

4. |

Gilbert S. Fell, "Blue Laws - A Minority Opinion," The Christian Century, Vol. 76 (Nov. 25, 1959), pp. 1373-1375. |

|

5. |

Presbyterian Life, September 1, 1962, pages 30, 31. |

|

6. |

Allan C. Parker, Jr., "I Don't Like Blue Laws." |

|

7. |

James McCord as quoted by Ron Timrite, "Puritan Handicap," San Francisco Chronicle, October 30, 1962. |

|

8. |

Religious News Service, April 26, 1963. |

|

9. |

Ibid., December 7, 1960 |

|

10. |

Ibid., May 24, 1965. |

|

11. |

"Adlai Stevenson Speaks on Sunday Laws," Liberty News. |

|

12. |

"Coin Laundries Held Illegal on Sunday," Long Beach, California, Press Telegram, June 28, 1961. |

|

13. |

"Cincinnati Court Favors Sunday Car Washers," Gasoline Retailer, February 6, 1963. |

|

14. |

"Hardly Ever on Sunday," Jackson Citizen Patriot, April 24, 1962. |

|

15. |

"Sunday Sales Ban Still Getting Laughs," Dowagiac Daily News, April 12, 1962. |

|

16. |

"Calling King Solomon! We Need You!" Saline Reporter, March 30, 1962. |

|

17. |

"A Few Rambling Ravings," Coldwater Daily Reporter, March 24, 1962. |

|

18. |

"More Credit Than They Deserved," Battle Creek Enquirer and News, April 19, 1962. |

|

19. |

Religious News Service, November 5, 1964. |

|

20. |

Ibid., December 30, 1964. |

|

21. |

"Sunday Sales Charge Set Aside," Washington, D.C., Evening Star, June 9, 1965. |

|

22. |

Religious News Service, June 3, 1965. |

|

23. |

Ibid., October 3, 1961. |

|

24. |

Ibid., June 29, 1965. |

|

25. |

Ibid., March 5, 1962. |

|

26. |

Ibid., July 9, 1963. |

|

27. |

Ibid., March 13, 1963. |

|

28. |

"All Missouri Sunday Sales Finally Legal," Los Angeles Times, March 20, 1963. |

|

29. |

Adlai Stevenson, as quoted in Liberty News. |

|

30. |

"City Bans Sunday Hair Cutting," Pomona Progress-Bulletin, August 1, 1961. |

[234] (Blank)

oooOooo

View a PDF version of this chapter

To Ancient SDA's ............ To "What's New?"