The Beatles' personal contribution to the

specially boxed introductory set of new Apple releases called The First Four was

the single "Hey Jude," backed with John's "Revolution". "Hey

Jude" had turned into a pop epic. Beginning with Paul's plaintive voice against

simple instrumentation, it built to a melancholy anthem of forty instruments and a chorus

of one hundred voices chanting a four-minute coda. To help publicize the release of

"Hey Jude," Paul decided to put the closed boutique at Baker and Paddington

Streets to some good use. Late one night he snuck into the store and whitewashed the

windows. Then he wrote HEY JUDE across it in block letters. The following morning, when

the neighbourhood shopkeepers arrived to open their stores, they were incensed; never

having heard of the song "Hey Juden" before, they took it as an

anti-Semitic slur. A brick was thrown through the store window before the words could be

cleaned off and the misunderstanding straightened out.

As it turned out, Paul need not have worried about such a small

publicity gimmick; "Hey Jude" became one of the biggest selling singles in

England in twenty years. Mary Hopkin's "Those Were The Days" sold almost as

well, and throughout the summer both songs fought for the top spot on the record charts,

selling a combined thirteen million copies in all.

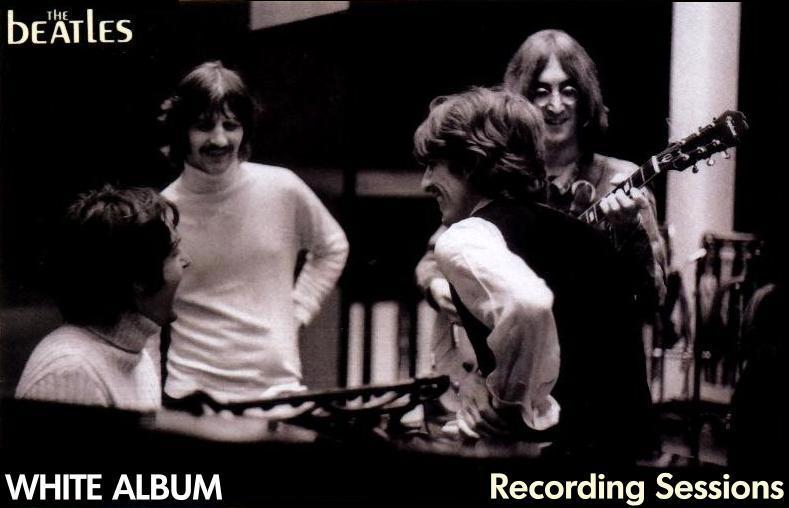

In its own right, the Beatles new double album was no less

successful. Entitled The Beatles, the album became known to the public as the White

Album, because of its stark, glossy-white laminated jacket, with the words, "The

Beatles," in almost invisible raised lettering. It was Paul's idea to have each album

individually numbered, like fine lithographs. And indeed, the White Album was a

work of art. The thirty songs on the two-record set took them an unprecedented five months

to record and mix. The critics were ecstatic at the huge selection and diversity of taste

on the LP, ranging from John's "Revolution 9," a taste of his experimental tapes

with a strong influence from Yoko, to Paul's pudding-sweet "Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da."

Tony Palmer, in the London Observer, raved, "If there is still any doubt

that Lennon and McCartney are the greatest songwriters sing Shubert, then . . . [the White

Album] . . . should surely see the last vestiges of cultural snobbery and bourgeois

prejudice swept away in a deluge of joyful music making. . . ." None of the critics

noted, however, that perhaps some of the album's diversity was due to the work of

individuals rather than the four Beatles working in collaboration. By the time of the White

Album sessions, the Beatles' working relationship had disintegrated to the point

where the only way for them to wrest control for the recording of his own composition

while the other played "backup band." This put Paul at the controls most of the

time, with John in second place, and George in a poor third with only four of his own

compositions on the finished album. George had so much trouble getting John and Paul's

attention that he even brought famed guitarist Eric Clapton into the studios with him to

use as his "session guitarist."

Ringo contributed hardly at all. He had finally become

superfluous to the Beatles. Most of the time he spent in the studio he sat in a corner

playing cards with Neil and Mal. It was a poorly kept secret among Beatle intimates that

after Ringo left the studios, Paul would often dub in the drum tracks himself. When Ringo

returned to the studio the next day, he would pretend not to notice that it was not his

playing. The fans never knew, but it must have cut him terribly. The message from Paul and

the others was clear; this little man who had lucked into the group and sailed with them

into the big times was not good enough musically to play with them.

One day Ringo arrived home after a recording session during

which Paul had lectured him on how to play, and he told Maureen tearfully that he

"was no longer a Beatle," that he had quit. Maureen was terrified at first.

Ringo sat at home for the next few days and brooded or played with his kids while the

recording sessions went on without him. When he got bored and peeved that the others had

not attempted to draw him back, he sheepishly announced that he was "returning to the

Beatles." The evening he arrived back in the studios the other three arranged to have

his drum kit smothered in several hundred pounds' worth of flowers. Ringo was delighted

and all was forgiven, but the rot had already set in; the foundation of the group was

cracking, and no amount of flowers would be able to cover it up.