NEWS: this version of the site is now defunct. For the new version (faster download, no ads), point your browser at http://www.jacobite.org.uk/maccaig/.

|

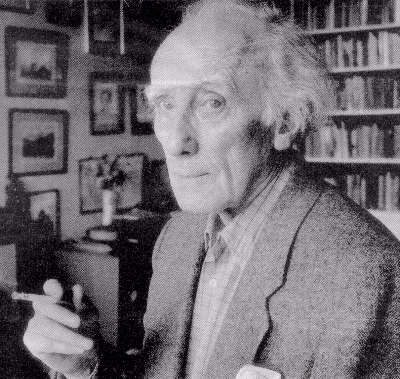

| Asked how long it took him to write a poem, MacCaig would reply "two fags" |

One suspects that to try to discuss Norman MacCaig's poetry at too much length would be against the spirit of the poetry and of the man himself. Apparently he used to have a favourite comment when marking well-meaning but student long-winded essays: "Study brevity".

It's in any case remarkably hard to comment on MacCaig's work, basically because the poems tend to be so neat and self-contained that there's very little to add without labouring a point. This has irritated some critics: the classic complaint is that he was "a major poet who wrote only minor poems". More intelligently, Douglas Dunn noted in the essay Language and Liberty, which forms the introduction to the Faber Book of Twentieth Century Scottish Poetry, that:

As a body of poetry made up for the most part of short lyrics, brief discursive narratives and satires, it can seem to resist identification as the work of a major writer. However, what finally marks it as such is the importance of themes, and the extent to which poem after poem seeks to define and clarify the individual's relationship to existence. It is a poetry of detailed resemblances that cumulate into a glimpse of "the whole world's shape".

In other words, what counts is the cumulative effect of the poems: in his commentary in 100 Sonnets, Don Paterson describes this effect as being "like tipping a bucket of gemstones out on the carpet". Nevertheless, Dunn devotes only a few paragraphs of his essay to MacCaig: ultimately, he's a writer whose importance you have to take on faith — until you've read him, when it becomes unarguable.

The other aspect of MacCaig's poetry which is rather elusive is the characteristic style of his writing. This is, again, less because of its obscurities or idiosyncracies than because of its lack of them — "lightness of touch, ... melismatic smoothness, a highly polished English — these were, and still are, unusual in Scottish poetry" (Dunn). Classifiers can also be frustrated by the shift in style between the earlier, more obviously technical poetry of the earlier collections, and the later, freer verse. However, this shift is less a fundamental change of style than a change in the relation between poet and audience. To quote Douglas Dunn yet again, the effect is that "his later poetry feels less 'literary'. It is also more open to achieving a direct form of address to reader or listener." A careful reading of the poems, though, finds the same themes revisited, the same canny use of the line-break and the Gaelic-informed intonation behind the words, and the same crowding of similes for an effect rather like an illustrated manuscript — compare, for example, Fetching cows with One of the many days: they're superficially different, but on a second reading quite clearly the work of the same writer.

Bearing these warnings in mind, there's still plenty to be said about the poetry. By way of a starter, here are a couple of links to articles on other websites. More will follow as and when I find them.

"No extra words": the Scottish Lyric Poet Norman MacCaig (Anette Degott, Institut für Anglistik/Amerikanistik, Jena): A good summary of the poet's work and development, from a German academic writer.

A man in Assynt: landscape in the poems of Norman MacCaig (Dave Pritchard, Centre for Environmental and Geophysical Flows, Bristol): A more personal take on MacCaig, from a rather different academic perspective.

Finally, on the Comments page on this site are some of my notes on and reactions to the poems included here. Any feedback on these, or any other links to relevant material, would be very welcome.