Z E B R A / Z I O N

Cameron McPherson Smith

August 1994

***Getting to the top is nothing.

How you get there is everything.

-- Geoffey Winthrop Young, 1928

...and again...

Chiu and I loaded the VW and headed for the north Cascades of Washington, determined to make a lightning, one-day ascent of the east face of Liberty Bell, a 300-meter granite spire which had repelled me in two solo attempts in 1993, and myself and Chiu in a paired attempt a month earlier.  Just when we were poised for success, having climbed the only difficult pitches, dark clouds appeared and shrouded the summit of the spire high above our ledge. We made a four-pitch retreat under a steady drizzle, rapping down heavy, sodden ropes (photo: Chiu jumars pitch 2 an hour before our retreat).The weather report, this time, was excellent. 10% chance of showers, partly cloudy, temperatures in the 60's. Perfect weather for alpine rock-climbing. We would carry only a litre of water, our gear and a waterproof jacket each, just in case. And, of course, the essential headlamp for the likely night-time descent. With our meticulous plans and good weather forecast, we sped northward on the familiar old I5, through Tacoma and Seattle and Burlington, then turned East on the North Cascades Highway for the last leg of our journey.All through our drive the weather was perfect, and our spirits were high. I savored the pre-climb butterflies. Passing Ross Dam, the last major landmark before reaching Rainy Pass and our campsite, we noticed some fast-moving clouds ahead and at a higher elevation. We said nothing as we chugged slowly up the highway. Dots of rain appeared on the windshield. Chiu refused to turn on the wipers until it was absolutely necessary. Within an hour it was raining in earnest.We pulled off the road, a mile from Liberty Bell, and Chiu killed the engine. Rain drummed steadily on the roof, the most lonely sound in the world...I put on a hat and jacket, exited the car and jogged into the forest, feeling the ground beneath dead logs. The soil was heavy with water -- it had been raining for some time: the clear weather had been a fluke, a 'sucker hole'... Completly dejected, I tramped back to the car and gave Chiu the bad news. The route would take at least two days to dry before we could climb. By that time we had to be back in Portland. The climb was off.We had driven 340 miles in 7 hours and were unable to accept the truth. Chiu cooked some noodles and we sat in the back of the wagon, with the rear door opened above us, and gulped down our meal, watching rainwater stream down off the roof of the car. We convinced ourselves that it was worth waiting one night -- that in the morning, by some miracle, we would find sunny skies and dry rock.We laid out our bags in the back of the wagon and tried to sleep. The last time I looked at my watch, the luminous hands glowing in the darkness, it was 2:30am, and the rain continued its relentless beat on the roof.I woke at 6am. More rain. It was true...we had driven seven hours for nothing. But we were desperate for action. I'd spent too many weeks in the lab -- and Chiu had labored over GRE reviews for too long -- to let these few days go without climbing something. We sat in the car discussing our options, craning our necks up at the spire occasionally to find it wreathed in cloud.Eventually we decided that our best bet for sure climbing was at Smith Rock, in Eastern Oregon. We packed our gear and started driving. Descending out of the mountains we left the alpine clouds, left behind the alpine meadows, and entered a realm of baking heat, the Eastern Washington highveldt. Down, down, down, ever southward. Ellensburg. Yakima. Goldendale. Columbia River. Madras. SMITH ROCK STATE PARK 5mi --->.After nine mind-numbing hours we arrived at Smith Rock. As we motored quietly along the gravel road, totally nixed by the marathon driving sessions, we silently read the new signs posted everywhere. The campsite now cost $5.00 per night, plus $2.00 per person per vehicle. Another new sign -- NO SLEEPING IN MOTOR VEHICLES. Also, a brand-new $3.00-a-day parking fee within the park. And a procession of NO PARKING signs lined the road leading to the park, in case you got any bright ideas. The options were limited.

Just when we were poised for success, having climbed the only difficult pitches, dark clouds appeared and shrouded the summit of the spire high above our ledge. We made a four-pitch retreat under a steady drizzle, rapping down heavy, sodden ropes (photo: Chiu jumars pitch 2 an hour before our retreat).The weather report, this time, was excellent. 10% chance of showers, partly cloudy, temperatures in the 60's. Perfect weather for alpine rock-climbing. We would carry only a litre of water, our gear and a waterproof jacket each, just in case. And, of course, the essential headlamp for the likely night-time descent. With our meticulous plans and good weather forecast, we sped northward on the familiar old I5, through Tacoma and Seattle and Burlington, then turned East on the North Cascades Highway for the last leg of our journey.All through our drive the weather was perfect, and our spirits were high. I savored the pre-climb butterflies. Passing Ross Dam, the last major landmark before reaching Rainy Pass and our campsite, we noticed some fast-moving clouds ahead and at a higher elevation. We said nothing as we chugged slowly up the highway. Dots of rain appeared on the windshield. Chiu refused to turn on the wipers until it was absolutely necessary. Within an hour it was raining in earnest.We pulled off the road, a mile from Liberty Bell, and Chiu killed the engine. Rain drummed steadily on the roof, the most lonely sound in the world...I put on a hat and jacket, exited the car and jogged into the forest, feeling the ground beneath dead logs. The soil was heavy with water -- it had been raining for some time: the clear weather had been a fluke, a 'sucker hole'... Completly dejected, I tramped back to the car and gave Chiu the bad news. The route would take at least two days to dry before we could climb. By that time we had to be back in Portland. The climb was off.We had driven 340 miles in 7 hours and were unable to accept the truth. Chiu cooked some noodles and we sat in the back of the wagon, with the rear door opened above us, and gulped down our meal, watching rainwater stream down off the roof of the car. We convinced ourselves that it was worth waiting one night -- that in the morning, by some miracle, we would find sunny skies and dry rock.We laid out our bags in the back of the wagon and tried to sleep. The last time I looked at my watch, the luminous hands glowing in the darkness, it was 2:30am, and the rain continued its relentless beat on the roof.I woke at 6am. More rain. It was true...we had driven seven hours for nothing. But we were desperate for action. I'd spent too many weeks in the lab -- and Chiu had labored over GRE reviews for too long -- to let these few days go without climbing something. We sat in the car discussing our options, craning our necks up at the spire occasionally to find it wreathed in cloud.Eventually we decided that our best bet for sure climbing was at Smith Rock, in Eastern Oregon. We packed our gear and started driving. Descending out of the mountains we left the alpine clouds, left behind the alpine meadows, and entered a realm of baking heat, the Eastern Washington highveldt. Down, down, down, ever southward. Ellensburg. Yakima. Goldendale. Columbia River. Madras. SMITH ROCK STATE PARK 5mi --->.After nine mind-numbing hours we arrived at Smith Rock. As we motored quietly along the gravel road, totally nixed by the marathon driving sessions, we silently read the new signs posted everywhere. The campsite now cost $5.00 per night, plus $2.00 per person per vehicle. Another new sign -- NO SLEEPING IN MOTOR VEHICLES. Also, a brand-new $3.00-a-day parking fee within the park. And a procession of NO PARKING signs lined the road leading to the park, in case you got any bright ideas. The options were limited. ****

Climbing here at Smith Rock -- as elsewhere -- was no longer a way of life, a fringe experience for the low-budget wanderer. It was becoming a 'hobby', a past-time for espresso-fueled, hyperactive yuppies who had no regard for the history or founding values of Alpinism, who were out for the immediate thrill. My only consolation was my conviction that these people weren't in it for the long haul. After ten years of climbing, watching its principles violated more and more each year as people soullessly pursued recognition and pure difficulty at all costs to the natural environment, I had to believe in something -- that there was some hope for the way of life that I love. However, my rationalizations were not simply, as Twight says, 'a digestive agent to counter the unpalatable'. I still believe that modern sport-climbing will die. It builds no philosophy of conduct that can carry it into the future. It feeds on itself. It will disappear, leaving countless bolts in rock around the world and white chalk stains marching lonely up steep, blank rock faces. Traditional climbers will set to work chopping these bolts. Years will pass. Some climbs -- those with heart -- will be spared. They will even be climbed again and again. But the majority will be erased by hammer and chisel, the bolt-holes filled with epoxy and painted to the color of the surrounding rock. Sport climbing will be dead and gone, but the empty and unnatural bolt-holes studding rock faces around the world will be one of the silent residues of the fad. Fitting.From the drivers' seat I watched as teenagers leapt around and played in the parking lot, anticipating the fun of the days' climbing to come. Many drove cars most likely borrowed from their parents - Oldsmobiles, Suburbans, that sort. They were here for the day. I watched one group of college students standing around their Team Van, munching croissants and sipping 'spro', pumped from vacuum flasks. Some sucked artificial fruit drink from straws impaled in small paper boxes, casting their empties like husks into the garbage can which sat next to a row of recycling bins.Where were the beat-up camp stoves, sputtering and boiling 'hobo coffee'? Where was the gritty parking-lot life of the underfunded teen climber, scamming plastic litre bottles from trash bins to use as water bottles? Where were the frayed old pile jackets and weathered shoes? Teva sport sandals, brand-new climbing tights, Ray-Bans. No holes, no duct tape, no patches. It was hard to belive, and hard to watch. There was no soul to this. There was only the instant. Their vapid comments set the tone: 'This is some nasty brew! What about heading back to town for a REAL java?''Ha! You gotta rough it out here, man.'. These kids, I thought, would pay the dearer price of the current sport-climbing trend. Precious few of them were learning to climb responsibly. Saftey was not an issue, because danger was eliminated in sport climbing. Fewer still were learning to climb in a way that taxed their composure and mental reserves. The majority were learning to 'climb' sport routes, basically ladders of small pockets and fingertip ledges, bright with chalk from countless previous ascents, and marked every six feet with a shining bolt set deep in the rock. Solid, safe. Most often these ascents were being made with the 'top-rope' method, where the rope was tied in to the climber's harness, relayed through anchors above the climb, and was belayed by a (normally inattentive) friend standing a few feet from the wall. A fall was nothing more than an embarrasment. A climb was nothing more than a challenge to overcome, by whatever means. You can hang on the rope and inspect the holds. You can take repeated falls while testing out moves. You can find climbs simply by spotting the chalk-marks on every useful hold and the ubiquitous line of bolts leading upward to the chained anchors at the top, often forty or fifty feet off the deck.With a generation of kids being brought up on sport-climbing, the search for adventure, the spirit of climbing, is being undermined. Undermined? Perhaps not. More accurately, it seems that the spirit of adventure -- seeking out and challenging oneself in the unknown -- is simply being replaced by something else. Something safer, easier and -- critically -- controllable and known.I'm not alone in these beliefs about the emptiness of sport climbing. Other traditional climbers are equally outraged and concerned by these developments. The usual response to their comments is that the 'trads' are being anachronistic, that since they can't climb these new hard routes, they are just jealously attacking that which they cannot control. Neither of these are true in my case.As for being anachronistic -- there are times when one must draw a line. Not all new developments are good. Not all traditions are good. Some traditions are useful, timelessly so, and cannot, thus, be anachronistic. Royal Robbins, an archetypal traditional climber of the 'Yosemite Era', once pointed out that if you agree that there must be some limit to what people do, you must draw a line somewhere in the realm of their activities. Some of the traditional goals and philosophies of climbing are good. These principles should score the lines of acceptable activity. They include the search for the unknown and the exploration of ones' own mental and physical limits. They also emphasize independence.As for the idea that I'm lashing out at sport climbers because I can't climb their routes, it simply doesn't stand. I don't want to climb their routes. Their routes do not stimulate me because there is no danger and the route is known. The fact that the climb is difficult is not enough.****

I reflected on all these matters as Chiu and I took a stroll to observe the current scene. The experience was as depressing as the climbers' questioning gazes at the helmets strapped to the tops of our packs.Later that afternoon, in a bid to avoid the throngs and the fees, we drove five miles to a patch of BLM land that in March was completely barren of 'facilities'. Now the land was a true American campsite, complete with a dizzying list of regulations, a visitor registration box, an ugly blue porta-potty standing amongst the junipers, and a large NO OPEN FIRES sign. Everything was changing, nothing was changing.*****

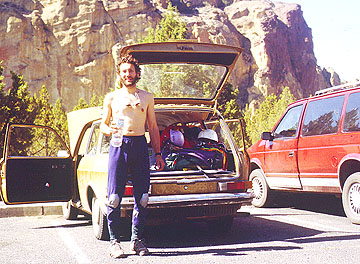

We woke the next morning determined to climb something. There were good routes at Smith, after all, but most people avoided the cracks and concentrated on the sport climbs. We loaded our pack in the parking lot, paid our rotten $3.00 and ambled down the trail. On the way, a van with Utah plates actually passed us on the wide trail, churning up dust which coated a second van follwing. Why they were driving down a trail which was an easy hike was a complete mystery. The passengers were smiling college students -- perhaps a geology field school? I was furious and Chiu and I decide to beat them down the trail, for no particular reason, just as a vent for our anger. We ran down the steep grade, taking gargantual strides, the force of gravity jarring our every footfall. We beat the vans to the bridge by three minutes. To me it was a wonderful feeling of triumph.We straightened our gear and started the walk towards the main climbing areas.By 8:30am we were poised beneath the crux section of 'Zebra', a 200-meter route soaring up cracks above the very popular 'dihedrals' area. Chiu had led the first pitch, a 40-meter rising traverse across and up a face gouged by giant pockmarks. He now hung from two bolts a few feet beneath me, sorting out the last of the ropes as I prepared for the ascent. I was standing on a small lip of rock with one foot, the other was jammed in a fist-sized crack.Chiu checked his knots, tightened his helmet strap and nodded up at me -- he was ready. Chiu settled back in his slings, leaning out from the wall and watching me carefully."OK," I muttered. Nervous tension rippled my guts as I chalked my hands. I was weak and trembling with fear. I doubted that I could lead this pitch -- the grade was 5.10a. Chiu and I normally climbed at this grade, but on shorter routes closer to home, with less hardware to slow us down and less exposure to terrify us.I turned away from Chiu, checked my tie-in knot and harness buckle, and looked up at the crack above me.From my stance, the crack jagged up ten feet to a small roof which jutted out about three feet from the face. It was impossible to go directly over the roof, as there were no holds on the face above it. Rather, I would have to climb up to the roof, then reach up and out to the crack between the the flake of rock which formed the roof and the main wall. I would have to jam my fingers in this crack, kick my feet free and then hoist myself up and over the roof, to where I could start climbing upwards again.I had had so many failures in the recent past...despite my terror, I was determined to get through this climb. I took a deep breath and exhaled slowly."OK, Chiu. Climbing.""Climb."Up I went, jamming my fingers and toes into the crack. The first moves were easy, but I didn't look down.I reached the roof and set my feet carefully on two ripples of rock. My left hand gripped the underside of a flake of rock at about waist-level. My right hand was free to reach up and grip the crack above the roof, but first I had to place some sort of anchor in case I should fall. Placing good protection efficiently is one of the critical skills of the traditional climber. There was no bolt here to simply clip to. I laid back off one arm while I searched the gear rack at my side for a cam...The first piece I selected was too large....the next piece was too small. My left hand - underclinging the crack - was sweathin profusely and getting pretty exhausted now, and I had to grip with the right and shake blood back into the left. I then re-slotted the left hand, freed my right hand and selected another piece of protection. I placed a TCU in the crack, clipped through and prepared to go up.It looked impossible. I knew that I had to go on, though. If I retreated without at least trying, I would have to live with my own cowardice. My protection looked adequate but small...I wondered whether it would hold a fall . Visions of potential disaster flitted through my mind's eye. For some reason, I decided to go on."OK, Chiu, watch me. I'm going for it." My voice probably quavered."...OK."I reached up, jammed my right fingers to the second knuckle in the crack and let most of my weight hang on that jam. It felt quite solid. I reached up and gripped the crack with my left hand, just above the right. Not so solid, but adequate. I found no footholds in a quick scan. Self-doubt rudely intruded, screaming at me to quit. It was too dangerous. The probability of falling was too great. I mustn't stress the anchors. I could retreat with dignity from here -- I'd tried, hadn't I? NO! Hanging there from my fingertips I battled the conflicting voices in my head. I once beat my helmet on the rock, raising a slight gasp from Chiu. It seemed that my whole life was concentrated and focused on what I did next. What would I do? Would I play it safe, and question myself for the rest of my life? Would it be possible for this to haunt me for the rest of my life? It may sound absurd to the non-climber, but there is the difference...it COULD haunt me...Could I draw on some unknown reserves and push my limits?Suddenly I pulled hard on my hand-jams and cast my feet free of the rock. I was hanging straight-armed from the eight fingers jammed in the crack, my feet swaying beneath me, the rope tailing down towards Chiu. It was dramatic, but terrible technique...I glanced once at a drop of sweat as it dropped down into the 40 meters of air below my swaying feet. I then turned my entire being onto the task of getting over the bulge.I contracted my muscles in unison and now found myself with my eyes level with my finger-jams. I was rapidly tiring, and I knew that I had only seconds to find a food-hold to take some of my weight. Ten pounds of gear shifted on my right hip, threatening to lever me out of my finger-jams. I held my breath for an instant and swung my right foot up towards the face. Now I was panting. The sole of my right foot smeared into a dimple of rock, and I pressed it inward. Somehow it held. My fingers were slipping now, just barely perceptibly. I knew that I had to instantly do something drastic. Pressing with all my strength on the right foot, I let my left hand out of the crack and slotted it two feet higher. The crack was wider there and my fingers did not jam well. My right fingers were slipping from the crack. My right foot was slipping more from the rock the harder I pushed on it. The left foot dangled below as if lame. I was out of control - everything was wrong. I was going to fall. I knew it. I felt it.At the moment that I decided to give Chiu a warning, my mind went into overdrive, pushing my body harder than ever in a desprate attempt to stay aloft. I yarded up on my finger jams with power I'd never believed I posessed. My right foot stuck miraculously to the rock face. Before I was really conscious of what had happened, I found myself standing straight up, my right foot on the horrible sloping hold, the toe of my left shoe jammed in the crack, my hands somehow jammed above me. I was over the roof. Chiu, below, stared at me wild-eyed. I could not remembner what I'd done to reach my current position. I stood panting and bewildered.****

That moment was one of the most important in my life. I had fought the self-doubt, the terror, the self-hatred that I dwelled on, and my mind decided to go forward; decided that I was finished with fighting myself, that I had to go on to salvage my self-esteem. The danger burned away the irrelevant aspects -- car trouble, my thesis, the total inability to carry on a decent relationship with a woman -- and focused all my attention to my own mind, where all the real problems lay. The physical exertion added to the danger, forming a ruthless crucible. Suddenly I learned about myself for the first time in years, and realized that my own mind had to be sorted out before I could be any use to anyone else, that I created my own problems by deceiving myself and running my life based on my self-deception.As dramatic for me at that moment as any of Marc Twight's writings, I realized that in that moment I had burned the house of cards and decided to start my life anew.****

But I was still in a desperate position. I was now ten feet above my last piece of protection. If I fell, which felt increasingly likely as I tired, I would take a twenty-five foot 'screamer' onto that little TCU. Surely, it would rip straight out. Below I could hear Chiu murmuring in delight and wonder at my overcoming the roof. At once I felt ill with fear and elated with what I had done. I selected another piece of protection from my rack and secured it into the crack, clipping the rope through effortlessly. A decade of climbing had made at least that aspect of the climb routine. I desperately wanted to grab hold of the piece, just to rest for a moment would be so nice. But I also wanted to do this climb in good style, to ascend the crack completely under my own power, to take up the gauntlet laid out by Geoffry Winthrop Young. I called down to Chiu that I was going to go on.The next 30 meters of the climb were a grind. I'd thought that the bulge lower down was the crux. Acrobatically, it was, but the climbing above was relentlessly stenuous: a lot of people can lead 5.9, but that was little comfort as I made my way upwards.... With my feet pressed against the face, I let my fingertips curl inside the crack. I then inched upwards, in the layback position. Occasionally I was able to stop and place a piece of protection, but the runout between the gear was very nasty. At one point there was no place to stop for ten meters, and when I looked down at my last piece of protection, facing a sixty-foot fall, I felt sick to my stomach and moaned in self-pity. There was no turning back, though.Suddenly it was all over. To my left a large ledge presented itself at eye level. I made the last, easy moves with the utmost delicacy, taking particular care not to blow it on the final, easy section which is the scene of so many mistakes as the impatient leader runs for the top up easy ground.****

Finally I heaved myself, panting and trembling and sweating, over the ledge. It was over. I'd led the pitch with no falls. I was proud, but also humbled. As I arranged belay anchors on the ledge I felt as if I were dreaming, as if I'd fabricated the whole scene. The wonderful thing was, I hadn't. This was real.As I hauled up the backpack, I realized that it was possible to go on from here, that I could, indeed, realize my climbing ambitions. For the first time in my life, I understood -- rather, felt -- what it means to say that 'the possibilities are frightening'.***

The rest of the climb was enjoyable, but I remember little other than my experience facing the crux roof...Chiu and I had had a great climb, and had salvaged our hopeful attempt at Liberty Bell.

All in all, we had succeeded on a climb we weren't even expecting to do. We drove home to Portland that afternoon, exhausted and elated.He is lucky who, in the full tide of life, has experienced a measure of the active environment that he most desires. In these days of upheval and violent change, where the basic values of to-day are the vain and shattered hopes of to-morrow, there is much to be said for a philosophy which aims at living a full life while the opportunity offers.There are few treasures of more lasting worth than the experience of a way of life that is in itself wholly satisfying. Such, after all, are the only posessions of which no fate, no cosmic catastrophe can deprive us; nothing can alter the fact if for one moment in eternity we have actually really lived.--Eric Shipton, 1942

***

***

CAMERON'S CLIMBING WRITINGS PAGE

CAMERON'S CLIMBING PAGE

CAMERON'S HOME PAGE