|

Copyright Renaissance Society of America Spring 1997

IT

IS SOMEWHAT SURPRISING, given the nature of royal investment in various

forms of political and religious iconography associated with

Renaissance portraiture, that the well-known "Rainbow Portrait"

(c.1600-03; fig. 1) of Queen Elizabeth I, held by Robert Cecil, Lord of

Salisbury at Hatfield House, but of unknown provenance,l has not

received sufficient attention to its political allegories. Much has

been made of the religious symbolism associated with the portrait,

especially by Rene Graziani, who argues, for example, that "Elizabeth

wears the gauntlet on her ruff in right of her title, Fidei Defensor,

official champion of the Christian religion" (255),2 and that the hair

style of the Queen with its "Thessalonian bride allusion. . .

[contributes] to the sponsa Dei theme" (259).3 No doubt conventional

religious symbols are at work in the portrait, but I would argue that

there is strong evidence to support a reading of the portrait as

primarily a political allegory, one whose religious dimensions underpin

an iconographic representation of sovereign self-investiture.

Graziani's conclusion that the "'Rainbow' portrait keeps a fine balance

between what belongs to the queen as a great Christian sovereign on the

one hand and on the other the confession of utter dependence on God"

(259) needs reevaluation, especially in terms of the so called "utter

dependence on God" that the portrait putatively manifests.

Roy

Strong's suggestion that the portrait is "above all a composite

portrait which has, like the 'Sieve' portraits, to be read as a series

of separate emblems as well as collectively" (1987, 158) emphasizes

less the religious aspects while underscoring the disparate elements of

the symbolism. This despite his general assertion that Renaissance

state portraits are meant "not to portray an individual as such, but to

invoke through that person's image the abstract principles of their

rule" (1987, 36). Strong hints at possible political readings of

Elizabethan portraiture when he suggests that images of Elizabeth

"produced after 1580 must have reinforced the concept of the monarch as

a being sacred and set apart, whose very jewels embodied the glory and

riches of the kingdom" (1987, 36). After a brief summary of Mannerist

treatises on painting by Ludovico Dolce and Paolo Lomazzo, Strong

concludes that "for the Renaissance neo-platonist the portrait painter

was concerned with the ruler . . . as the embodiment of the 'Idea' of

kingship" (1987, 37). Surprisingly, Strong does not elaborate on these

views in his reading of the "Rainbow" portrait. Instead, he focuses on

the diverse elements of its symbolism, ranging from representations of

the Pax Elizabethae, to conventional representations of the Queen's

virtues of wisdom and prudence, to symbolism associated with the

"springtime renovatio of the golden age" (1987, 160), all of which

suggest a diffuse and rather cliched political symbolism at work.

A

via media exists between Graziani's and Strong's authoritative

readings, which I wish to develop in this essay. A number of features

in the portrait combine to form a forceful, political allegory that is

presented within a complex skein of allusions, not all to be read in

terms of traditional iconography. Strong in fact notes that if the

portrait is attributed to Marcus Gheeraerts, "it would have to be

placed among his most adventurous compositions" (1987, 161), suggesting

that the resonances of the portrait, whoever drew up its program,4 may

not have been wholly within the interpretive traditions of Elizabethan

portraiture.

|

|

The

portrait, no doubt, is a hybrid-aesthetic, religious, literary, and so

forth-but it is a hybrid designed in such a way as to occlude the overt

political significations that would have undermined it as political

representation. The very fact that commentators have missed or ignored

the political symbolism at work in the portrait indicates either that

it is so obvious as not to warrant mention, or that it is so cleverly

concealed as to be virtually unnoticeable. If the latter option is

indeed correct, then the highly accomplished technical features of the

painting may well serve to distract viewers from the cryptic and

dissimulative artifices that are the keys to the portrait's allegorical

dimensions. Those dimensions include the political insofar as the

portrait comments on monarchic governance in the anxious, historical

contexts of a sovereign who, without direct heirs, was near the end of

a reign in which some measure of political stability, however illusory,

had been achieved. Though commentators have averted their eyes from the

political dimension, preferring instead to reflect on the general

structure of the portrait,5 it seems clear that the portrait intends a

political allegory, however concealed, that comments on the dimensions

of the absolute ideology it enacts. But what evidence can be brought to

bear on such an argument?

First is the obvious

misrepresentation and distortion of the aged Queen's body and face that

the portrait constructs. Strong has noted the "use of the established

Mask of Youth image of the Queen" (1987, 161), an allegorical

representation of dissimulation in which the monarchic presence is

invested with supranatural powers over corporeal disintegration, thus

confirming her association with an ex illo tempore world. Susan Frye

observes, in this last regard, that

Although Elizabeth

frequently admitted the consequences of her aging, her iconographic

response to the fear of premature burial was to claim herself ageless.

The inherent claim was that her active virtue, so often particularized

as her virginity or chastity, protected Elizabeth from the aging

process, helping preserve her metaphoric fertility in the guise of a

continuing physical fertility. Her represented denial of old age was an

assertion of her political viability, an attempt to transcend her

society's tendency to disparage and ignore any woman past childbearing

age - without, however, challenging that prejudice. As usual,

Elizabeth's selfrepresentation made no claim for women as a whole, but,

rather, sought to distance her from normative constructions of the

feminine. (100-01)6

Hence, political viability, the capacity to

sustain the illusion of sovereignty, entails for Elizabeth the

assertion of a position outside orthodoxies relating to the

representation of feminine aging. Sovereignty, in the curious logic of

iconic representations of the Mask of Youth, denies the norm even as it

seeks to perpetuate the norm against which the sovereign is defined and

without which he or she would not have hierarchical place. Mary E.

Hazard writes that "the appearance of the Queen under the Mask of Youth

or Beauty [in the Rainbow portrait] constitutes an iconic

representation of the legal fiction of the monarch's two bodies .... If

the king never dies, by the same logic, the queen never ages: the body

of the monarch lives in a perpetual present" (79). The fiction of a

"perpetual present," outside the normative conception of time, was a

significant dimension of iconic representations of absolute power, the

icon itself having extra-temporal resonances that were useful in the

construction of illusory images of absolute power. To subject the

sovereign to time was to undermine the symbolic fiction of absolutist

practice as occurring in an ex illo tempore, divine dimension from

which it gained its putative authority.

But such an ex illo

tempore world is not wholly spiritual or Godly. Rather, such a world

revokes the viewer of the portrait to the powers of mimesis itself, the

mimetic achievement of the portrait being its capacity to rewrite the

realities of corporeal function. Such a rewriting, by way of what is in

effect a form of anti-mimesis, has political consequences. The "reader"

of the portrait is thereby ensnared in the following knot: on the one

hand, the portrait is obviously a distorted version of an elderly woman

in her late sixties; on the other hand, the willful distortion enhances

the force of mimesis in its ability to rescript reality. The latter is

clearly what underlies the metaphysical dimensions of the absolute

monarch, who is absolute only insofar as he or she is capable of

sustaining the fiction of that absoluteness through the distortive,

anti-mimetic techniques of literary, iconographical, and public

representations of his or her body, his or her will. Thus, the very

premises of the portrait ensure that the covert political foundations

of absolutist ideology engage the viewer much in the same way that the

words Elizabeth is said to have spoken to her troops prior to the

Armada enable the potent association between the literal and figural

body of the monarch: "I know I have the body of a weak and feeble

woman, but I have the heart and stomach of a king, and of a king of

England too" (cited in Montrose, 315).7

The ineluctable

political logic underlying the portrait is that the Queen possesses

unseen powers over all acts of representation, powers that fly in the

face of even the most egregious distortions of reality relating to her

body and what it represents.

A second element of the portrait

that has not received much commentary is the Queen's cloak, with its

eerie depiction of eyes and ears facing out toward the viewer. Strong

associates these with verses from Henry Peacham's Minerva Britanna

(1612), in which a similar cloak is worn by Ragione di Stato (Reason of

State) in imitation of an emblem from Cesare Ripa's Iconologia (Rome,

1593): "Be seru'd with eies, and listening eares of those / Who can

from all partes giue intelligence / To gall his foe, or timely to

prevent / At home his malice, and intendiment." Strong continues on to

say that "Peacham is using the ears and eyes in the same way that John

Davies refers to the Queen's use of her servants . . . in his first

entertainment in 1600: `many things she sees and hears through them,

but the Judgement and Election are her own" (1987, 159). The point is

well-taken, especially in the context of James VI and I's similar

comments in the second book of Basilikon Doron (1597): "And shortly,

follow good king Davids counsell in the choice of your seruants, by

setting your eyes vpon the faithfull and vpright of the land to dwell

with you" (168). Even more relevant, however, are comments James makes

at the conclusion of book two of the Basilikon Doron, where he

effectively states to Henry that his subjects, "by their hearing of

your Lawes . . . [and] by their sight of your person, both their eyes

and their eares, may leade and allure them to the loue of venue, and

hatred of vice" (179). The political implications of love of virtue and

hatred of vice are noteworthy, for it is precisely by encouraging such

emotions that the monarch defines his or her subjects' subservient

relations to the absolutist state, the moral standard against which all

ideology is to be measured and regulated. James's advice, then, has not

so much moral or didactic implications relating to the religious

conduct of his subjects but rather to their political conduct. The king

or queen signifies quite literally the embodiment of the laws and

virtuous attributes that ensure the State's survival.

The eyes

and ears evident in the "Rainbow" portrait, when read in such a

context, do not signify fame, as Frances Yates has suggested in a

reading discounted by Strong.8 Nor do they simply and univocally

signify the Christian imagery that Graziani gives them by way of

Matthew 13:16-17 ("Blessed are your eyes, for they see, and your ears,

for they hear"). "In the portrait," Graziani argues, "we are to

understand that the Queen wears this blessing like a cloak or mantle.

She is one who has seen and heard, an exemplary Christian and someone

specially favoured" (256). Though this may very well be the case it

hardly tells the whole story, for it assumes that the pose of the

exemplary Christian occurs only within a religious context, not the

larger context in which such a pose had its obvious political uses.9

Elizabeth was a pragmatist, both political and religious, and kept her

eye firmly on the secular dimensions of religious squabbling, going so

far as to state in a letter to James that "I am of this religion, qui

vadit plane, vadit sane" (168). Christian rhetoric was a conventional

tool of political artifice for Elizabeth and the purely religious

reading is too narrow an explanation of what the eyes and ears in the

"Rainbow" portrait signify, especially within the context of Strong's

argument regarding the portrait's composite symbolism. Instead the eyes

and ears echo the watchful gaze of the Queen, proliferating that gaze

and twinning it with the attentive ears that attend to the viewer's

relation to the portrait. The symbolism, then, is closer to the

Benthamian or Foucauldian panopticon10 than it is to the religious

zealot blessed by divine intervention. The Queen watches and listens

vigilantly, seeing from all perspectives, hearing in all directions,

the image perhaps distantly echoing the motto seen on the globe that

appears in Quentin Massys the Younger's Sieve Portrait: "Tutto vedo e

molto mancha" [I see all and much is lacking]. Surprisingly Strong, who

is an adept and sensitive reader, misses precisely this point in the

emblematic poetry he cites from Peacham.ll The function of the eyes and

ears is political service that gives "intelligence" that galls foes,

preventing their malice and the achievement of their "intendiment."

That Ragione di Stato is wearing such a garment in Peacham's emblem

merely reinforces the garment's political context, one that is

refracted in the portrait's political allegory.12

The closest

readers of this portrait have gotten to such an observation is Francis

M. Kelley's comment, cited by Graziani in a footnote, that "the coiled

snake and ears and eyes suggest her ceaseless vigilance" (247, n. 4),

and Frye's observation that the portrait "depicts an assemblage of

iconographic elements that claim the queen's chaste body as the center

of the Ptolemaic universe while wrapping her in a mantle whose open

mouths, ears, and eyes form a disquieting suggestion of vaginal

openings combined with a sense of governmental surveillance"

(102-03).13 Frye does not develop her "suggestion of vaginal openings"

nor their relation to government surveillance, if any at all. Reading

the folds in the mantle as mouths - themselves a visual metonymy for

the vagina - is extremely problematic with regard to the apparent logic

of the portrait's representation of the "queen's chaste body." This

problematic is further heightened by Strong's outright declaration that

"the golden cloak is adorned with eyes and ears but not with mouths

(eliminating the usual misreading of it as Fame)" (1985, 122).

Nonetheless,

if the erotics of the portrait entail a contemporary reading of the

mantle's folds as mouths or vaginas, the political dimension of the

queen's erotic allure cannot be ignored. Joel Fineman, in a brief

discussion of the Rainbow portrait's "fetishistic erotics," aligns

those erotics with "an equally fetishistic principle of sovereign

power" (228). Fineman is transfixed by the portrait, commenting that

what

is genuinely mysterious and surprising about the Rainbow Portrait,

especially if we assume this large picture was originally displayed at

court, is the way the painting places an exceptionally pornographic ear

over Queen Elizabeth's genitals, in the crease formed where the two

folds of her dress fold over on each other, at the wrinkled conclusion

of the arc projected by the dildo-like rainbow clasped so imperially by

the Virgin Queen .... In reproduction, the vulva-like quality of the

ear is perhaps not so readily apparent, but, enlarged and in florid

color, the erotic quality of the image is really quite striking, as is

the oddly colorless quality of the rainbow, a kind of dead rainbow.

(228)

John M. Archer reads the folds as "tongues" (4), the

shift from Frye's to Strong's to Fineman's to Archer's interpretation

of the folds indicating the difficulty critics have had in attributing

meaning to the fold, itself a particularly canny iconic representation

of a sliding signifier.t4 The painting clearly eroticizes Elizabeth's

body, whether or not one sees the portrait in the same way as Fineman,

Frye, Archer, and Strong. The ambiguous folds, in combination with the

vaguely phallic rainbow and the string of pearls looped suggestively

round Elizabeth's genital area, image an erotic potential complicit

with the sovereign vitality the portrait projects. Moreover, the

capacity to transfix with both an erotics of ambiguity and an ambiguous

erotics fortifies the absolutist dimensions of the portrait, for

Elizabethan absolutism depended on precisely such an effect both to

create its allure and veil its weaknesses. The power of erotic display

is not easily separated from the representation of absolute power, as

is demonstrated in, to cite but one of many examples, Holbein's

depiction of Henry VIII sporting a prominent codpiece - a painting,

incidentally, that was hung in the Privy Chamber at Whitehall, a place

not without its potent political resonances.15 Furthermore, if the

queen's left hand, with its index finger inserted in one of the

mantle's folds has some sort of masturbatory significance, again if one

accepts Frye's sexualized reading of the mantle's folds, then the

painting seems to be asserting, however cunningly or ambiguously, the

Queen's sexual aloofness, itself a metonymy for her political

uniqueness.16 The portrait may slyly hint, however shocking such a

suggestion may be, at the nature of the unmarried queen's autonomous

sexual practices while also affirming the queen's political authority

by virtue of the gaze she maintains and the intelligence she receives

while touching herself. She is, quite literally, the "unmoved mover"

(Belsey, 20) and the embodiment of her motto, semper eadem, the "always

she" around whom political and sexual autonomy are gathered like the

folds of her mantle. The effect is similar to what Mary E. Hazard

describes in her analysis of the Hampton court portrait of Elizabeth I

and the Three Goddesses (monogrammist "HE"):

The objects of her

gaze become subject to the queen even as her portrait is subject to the

gaze of the viewer, and with similar paradoxical effect. Fixed as

iconic subject, the image of the queen reciprocally acts upon a

community of viewers, reminding them in turn of their status as

political subjects, for dominance over the viewer is an implicit effect

of icon, a conventional genre designed to evoke uncritical submission.

In a very real sense, both the figures in the painting and the viewers

without are objects beneath her regard. (64)

Furthermore, if

the supposed rainbow that Elizabeth grasps in her right hand has any

erotic significance related to masculine, or phallic, sexuality, the

portrait further complicates its representation of the queen's

sexuality. On the (literally) one hand, the queen holds the unusually

shaped cylinder (as opposed to the more common, one-dimensional, flat

representation) of the colorless rainbow. On the other hand, the queen

fingers a fold whose visual ambiguousness parallels that of the

rainbow's. Phallic representation is undercut by the more subtle visual

and figurative resonances of the fold, which refuses to be read except

in terms of its ambiguities as mediated by the centrality of Elizabeth

as an emblem of empowered femininity.

The portrait's

compositional balance entails an erotics in which the queen exerts

control over the masculine, a control that may in fact be further

heightened by the sexual autonomy suggested in the positioning of her

left hand. A further possibility is that the Rainbow emblematically

endows her with masculine attributes and that, in a sense, she becomes

male by virtue of her grasp of its cylindrical shape as it descends

into and merges with her anatomy.17 The rainbow is visually preeminent

in the portrait while the left hand's relation to the fold is

subordinate, functioning more as a Barthesian punctum than anything

else.ls Thus the symbolic logic of masculine hierarchy is maintained

even as it is subverted by the portrait's obvious depiction of female

empowerment, or even, to use Constance Jordan's term, "political

androgyny" (157). In effect, if one accepts such a reading, the

portrait rescripts the sovereign's potency in terms of both masculine

and feminine agency. Such a rescripting fulfills the symbolic logic of

absolutist hierarchies whose traditionally patriarchal assumptions had

to assimilate the gender displacement caused by Elizabeth's accession

to the throne. The autoerotic valences the portrait may generate

reflect what Philippa Berry calls the "gynocentric cult of an unmarried

queen," in which the "emphasis of the love discourses [of Petrarchism

and Renaissance Neoplatonism] upon masculine subjectivity was to be

seriously undermined" (38). The portrait inverts and re-tropes the

traditional dynamics of sexual representation, which, as Archer states,

involved making women the subjects of sexual surveillance by men" (53),

while sustaining the illusion of that traditional dynamic. Thus,

Elizabeth as icon becomes subject to the gaze of the observer. But at

the same time the symbolics of the portrait reshape the observer's

gaze, subjecting it to the density of allegorical conceit, political

allusion, and erotic ambiguity that Elizabeth as representation

instantiates."

The fraught politics of Elizabethan female

self-representation required a substantial shift in iconic

representations of what had traditionally been the domain of "masculine

subjectivity," especially if one accepts Mark Breitenberg's suggestion

about the "essentially iconic nature of Renaissance interpretive codes"

(4). The shift necessarily generated visual and verbal ambiguities

burdened with interpretive possibilities that remain difficult to

reclaim with even the most informed historical hindsight. The obscure

erotics of the Rainbow portrait, its visual representation of what

Berry refers to in a discussion of Spenser's Cantos of Mutability as

"an indecipherable feminine figure" (165), attest to the power,

political and otherwise, framed in the very elusiveness of its mise en

scene.20

A further symbolic dimension to the eyes and ears,

missed by previous commentators on the portrait, is its relation to

Ripa's emblem for "Gelosia" in the 1603 version of Iconologia. The

emblem depicts a "Donna con vna veste di torchino a onde, dipinta tutta

d'occhi, e d'orecchie, con l'ali alle spalle, con vn gallo nel braccio

sinistro, & nella destra mano con vn mazzo di spine" (194; see fig.

2). Ripa explains that *Gli occhi, & orecchie dipinte nella veste

signifi cano l'assidua cura del geloso di uedere, & intendere

sottilmente ogni minimo atto, & cenno della persona amata da lui"

(194). The eyes and ears on Elizabeth's cloak, when seen in such an

emblematic context, signify her jealous relation, what Archer calls her

"scopic anxiety" (42), to the body of the commonwealth that is her

beloved (the "persona amata"). They demonstrate the assiduous care she

takes in subtly hearing and seeing the smallest acts and signs shown

her by the body of the commonwealth. In addition, the eyes and ears

give emblematic context to another Elizabethan motto, video et taceo,

'I see and remain silent," suggesting that the inscrutability of her

gaze and the ambiguous potency of her silence are key features of her

public representation of monarchic authority. Ripa's comment that

"Gelosia e vna passione, & vn timore" (194), that jealousythe

ambiguous significance of the eyes and ears, for they embody both

Elizabeth's love of the commonwealth and her anxiety with regard to the

potential threat it poses against her reign. Thus, the eyes and ears

symbolize the crucial dimensions of absolutism, torn between jealous

love and fear of loss, both of which can only be insured through the

perpetual vigilance that figuratively covers and protects Elizabeth's

sovereign body.21

The third notable element in the political

allegory, and one that has similarly been overlooked by major

interpretations of the portrait, has to do with the so-called rainbow

that the Queen grasps with her right hand, above which is appended the

Latin tag, Non Sine Sole Iris, or "No rainbow without the sun." The tag

confirms the emblematic context of the portrait, providing an obscure

gloss on the portrait's meaning. For Graziani, the rainbow fits its

sixteenth-century context as a religious icon, "notwithstanding the

fact that Italian artists were tending to discard it in its traditional

contexts [related to the Sacrifices of Noah]" (251). Graziani continues

on to argue that "the Queen grasps the rainbow as a token of protection

and assurance, very much in the spirit of a later Protestant

expression, `taking hold of God's promises" (252). Strong suggests the

rainbow as a "traditional symbol of peace" (1987, 158), allying it with

notions of the covenant made between God and Noah after the Flood: "I

do set my bow in the cloud, and it shall be for a token of a covenant

between me and the earth" (Genesis 9:13). For Graziani, as for Strong,

the Biblical symbolism is dominant, and there is no question that

readings which fail to note such associations are seriously flawed.

Again,

however, such a reading is far from complete within the context of the

political allegory at work in the portrait. Elizabeth's grasp of the

rainbow extends notions of Biblical covenant in a manner hitherto

unnoted, for unlike Noah, who does not touch the rainbow, Elizabeth

does. Furthermore, the rainbow is primarily a symbol of divinity, set

in place by God, as a reminder to God, of the covenant made: "and I

will look upon it, that I may remember the everlasting covenant between

God and every living creature of all flesh that is upon the earth"

(Genesis 9:16). Thus the rainbow becomes in such a context a highly

charged covenantal symbol that is grasped by Elizabeth as an emblem of

her proximity to divine authority as well as of her capacity to mediate

between the divine and the earthly. Her ability to grasp the covenant

signifies the alignment of her power with divine power, the alignment

of her perspective in remembering her covenant with her subjects with

that of God's, who, we must not forget, sets the rainbow in place more

for divine than for human benefit. In other words, the rainbow

establishes the covenant from the perspective of the top of the

hierarchy, whether divine or monarchic, suggesting a cosmic alliance

between the two that is enabled by Elizabeth's potent capacity to grasp

the nature of the covenant.

The political implications, though

highly conventional, are profound, for the suggestion is that Elizabeth

is empowered by her proximity to the divine and that she is in some

senses a simulacrum of that divinity. The Latin tag may thus be read,

within quite a different context, as referring to the Queen's presence

as a marker for divine presence. The Queen holds forth the rainbow by

virtue of the divine light she emits, not the rainbow without the sun

coming to emblematize the power that radiates from the Queen as a

function of her proximity to the divine. "[T]he Queen is lit," as

Strong observes, "neither from the left nor from the right but actually

seems to radiate light as she moves before the arch that encompasses

her figure" (1987, 160). Elizabeth's radiation of light coincides with

the type of the Tudor Godly Woman as emblematized in the biblical type

of the "Woman Clothed with the Sun (Rev. 12)," a figure that

characterized, according to John N. King, "representations of Queen

Elizabeth as. . . wise and faithful" (1985, 50).

|

|

But

the rainbow as a symbol, however oblique, of the "Woman Clothed with

the Sun" is not the only divine woman with whom it may be linked.

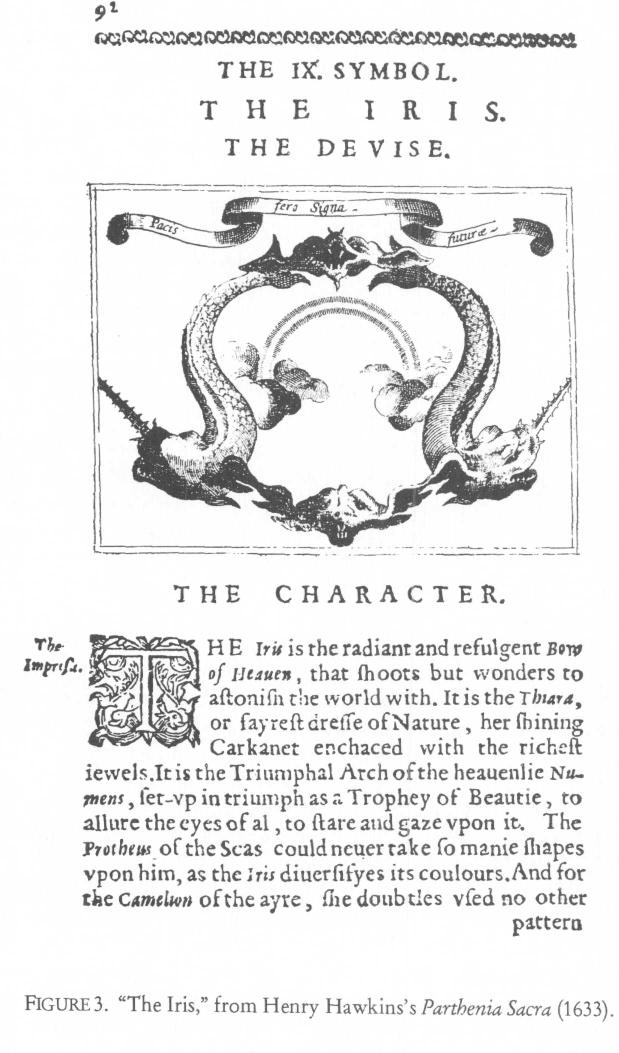

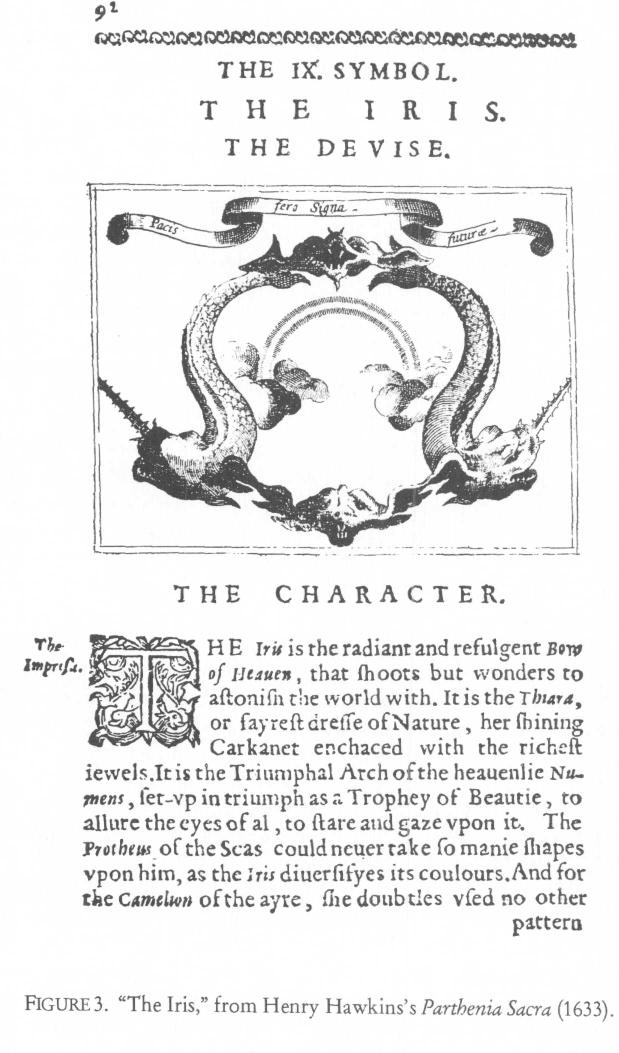

Images from Henry Hawkins's emblem book structured around a series of

Marian devotions, Partheneia Sacra, or, the Mysteriovs and Deliciovs

Garden of the Sacred Parthenes (1633), use "The Iris" to reinforce the

devotional importance of the "Virgin of Virgins" (Hawkins, 94; see

figs. 3 and 4). "The Devise" of the "Iris" functions for Hawkins as

"the Triumphal Arch of the heauenlie Numens, set-vp in triumph as a

Trophey of Beautie, to allure the eyes of al, to stare and gaze vpon

it" (92). Hawkins argues that "this heauenlie Bow deciphers the Queen

of Heauen, this mirrour of Nature, and the astonishment of man-kind"

(96), and goes on to suggest that "the grace of GOD being a ray, as it

were, of the Diuine Essence, reflecting on the purest Virgin, a lucid

clowd, concaue and waterish, produced the Iris or Rainebow in the

Hierarchie of the Church, as in the firmament of the Heavens; and

therefore called the Iris or Celestial Bow, a signe of the

Reconciliation of GOD with al mankind" (97). In his concluding

apostrophe to the "Iris," Hawkins invokes "my most deer Diuine Mother"

to guard me with the bow of thy safeguard and protection" (102;

mispaginated as 122), again confirming the sacred associations of the

rainbow with the Virgin Mary.22 The rainbow emblematizes Mary's

virginity, allure, and beauty, her ability to mirror and astonish, her

queenliness and capacity to reconcile and protect, all virtues that had

political resonances during Elizabeth's reign. These virtues, at once

sacred and profane, may well be encapsulated in the Rainbow portrait's

symbology.

|

|

|

|

Even

though the Partheneia Sacra appeared well after the presumed dating for

the conception and execution of the Rainbow portrait, its symbology

nonetheless allows for the rainbow as a potential signifier of divine

virginity, let alone as a "token of protection and assurance"

(Graziani, 252) or as a "traditional symbol of peace" (Strong, 1987,

158). Frances Yates, tracing some of the symbolic links between the

Virgin Mary and Queen Elizabeth, suggests that many of Queen

Elizabeth's virginal symbols - including the Rose, the Star, the Moon,

the Phoenix, and the Pearl, all of which, incidentally, are to be found

as emblems in Hawkins's Partheneia Sacra - "were also symbols of the

Virgin Mary" (78). Yates proposes the possibility, however "daring" or

"startling" (78), that "the cult of the virgin queen, was, perhaps

half-unconsciously, intended to take the place of the cult of the

Virgin" (78), and uses as her evidence a Dowland lute song that links

the phrases "Vivat Eliza" with "Ave Mari," an engraving of Elizabeth

that notes Elizabeth's birth on the "Eve of the Nativity of the blessed

virgin Mary" and her death on the "eve of the Annunciation of the

virgin Mary" (78), and some of the "chants of the university poets" at

Elizabeth's death, in which "one of the names used of Elizabeth by her

poets, namely `Beta,' is assimilated to `Beata Maria" (79). For Yates,

the "mysterious" symbolism used to represent Queen Elizabeth also had

ties with Astraea-Virgo, who symbolically echoes the Virgin Mary (80).

Read in this polysemous context, the rainbow redoubles Elizabeth's

divine associations, connecting her allegorically with both the Woman

Clothed with the Sun and the Virgin Mary, thus adding to her iconic

stature as an incarnation of divine (and virginal) empowerment.

The

secular symbolism of the rainbow, though difficult to dissociate from

its sacred symbolism, also has significance in political terms. Janet

Arnold, for instance, notes that the rainbow "appears in [Claude]

Paradin's Heroicall Deuises [1591] with the motto `The raine bow [sic]

doth bring faire weather,' and this text: `The most faire and

bountifull queene of France Katherine used the signe of the rainebow

for her armes, which is an infallible signe of peaceable calmenes and

tranquillitie" (84). Paradin's symbolic sense of the rainbow is echoed

in George Wither's A collection of emblemes, ancient and modern (1635),

which figures a rainbow and sun appearing over storm clouds, with the

epigrammatic commentary that "the rainbow brings promise of the sun

after a storm; so man should have hope that God will relieve his

sorrows" (cited in Diehl, 172). Though impossible to determine the

extent of the intertextual associations among Paradin's, Withers's and

the Rainbow portraitist's use of the rainbow, the association of the

rainbow with monarchic virtues of "peaceable calmenes and

tranquillitie" made it an appropriate device in Elizabeth's

iconographic repertoire. And, in fact, the rainbow portrait is not the

only instance in which Elizabeth made use of its symbolism; Arnold

states that "The rainbow is used as an embroidery motif on many of

Elizabeth's gowns and may be seen on one surviving fragment of a smock"

(84). Ultimately, the secular symbolism of the rainbow as an emblem of

hope, tranquillity, wisdom, and faith cannot be separated from its

sacred symbolism as emblematic of the divine presence that empowers the

absolute monarch.

But the Rainbow portrait, while seeming to

point to the convergence of these sacred and secular symbolic values in

the image of the rainbow, also leaves room for considerable ambiguity

in how that image is to be interpreted. A rather puzzling detail of the

painting, already noted in comments made by Joel Fineman, has a direct

bearing on how one reads the rainbow symbolism. The rainbow's obvious

lack of discernible rainbow colors - red, orange, yellow, green, blue,

indigo, violet - in a painting that is "rich in coppery hues" (Pomeroy,

64) and in other forms of chiaroscuro light, would seem to suggest two

somewhat contradictory possibilities.24

On the one hand, the

lack of rainbow colors may well be a subversive undercutting of

Elizabeth's symbolic magnificence, the anonymous painter figuratively

undermining Elizabeth by showing her in a situation where no rainbow

shines because there is no sun - that is, because Elizabeth's

magnificence is false or in decline. Such a strategy would be in direct

violation of an account Nicholas Hilliard gives in A Treatise

Concerning the Arte of Limning (c. 1598-99) of Elizabeth as

portait-subject carefully choosing "her place to sit . . . in the open

ally of a goodly garden, where no tree was neere, nor anye shadowe at

all, save that as the heaven is lighter then the earthe, soe must that

littel shadowe that was from the earthe" (29). Hilliard characterizes

Elizabeth's request as "curiouse" before going on to admit that

Elizabeth's demand had "greatly bettered my Judgment besids divers

other like questions in Art by her most excelent Majestie which to

speake or writ of, weare fitter for some better clarke, this matter

only of the light, let me perfect, that noe wisse man longer remaine in

error of praysing much shadowes in pictures" (29). Elizabeth clearly

had little sympathy for the use of shadow in limned work if only

because, as Hilliard puts it, to best "showe ones selfe, nedeth no

shadow of place but rather the oppen light" (28-29). The Rainbow

portrait obviously and perhaps subversively contradicts the philosophy

of representation implicit in such an observation - a philosophy that

is at pains to empower the object of the painter's scrutiny - by

framing Elizabeth's presence in shadow. The symbolics of the Rainbow

portrait, when read in the context of Hilliard's anecdote, may be seen

as inflected with resistance to Elizabeth's efforts to control the

aesthetics of her public representation. Thus, the shadows engulfing

her image may portend the twilight of her reign, and the fact that

rainbows are impossible in the crepuscular light she emits. No rainbow

shines, literally, because there is no sun to illuminate it.25

On

the other hand, the lack of color in the rainbow - of which Elizabeth

Pomeroy says, "but, strangely, the little arc she holds is not nearly

as colorful as her own hair and cloak" (65) - may well indicate

Elizabeth's surpassing relative significance in relation to the natural

world, her place near the top of the hierarchy being confirmed by her

luminescence, which contrasts so vividly with the pale arc she holds in

her hand. Her grasp of the rainbow emblematizes the symbolic union of

Elizabeth's physical body with the divinity that authorizes it to

represent the body politic, the portrait echoing Francis Bacon's notion

that "there is in the king not a Body natural alone, nor a Body politic

alone, but a body natural and politic together: corpus corporatum in

corpore naturali, et corpus naturale in corpore corporato."26 No

rainbow shines because it is outshone by the Queen's own brilliance,

her own surpassing light, her incarnation of political will authorized

by the divine. Thus, though it is tempting to say that no rainbow

really exists in the portrait, the politics of its representation as

absence or presence have a great deal to do with how one reads its

significance, either as a referent for the decline of the absolute

power invested in the monarch, or as a mark of her overshadowing

presence that obscures or transforms the many colors of the rainbow

into the uniform light generated by Elizabeth's sovereign powers.27

Furthermore,

the rainbow and its tag cannot be separated from the political contexts

established in Michael Neill's reading of the portrait as emblematic of

Elizabethan imperial ambitions in Ireland. For Neill, the Rainbow

portrait is "the last of the series of great royal icons in which the

queen identified the idea of the nation with the display of her own

royal body," and is a "frightening assertion of a royal power so

absolute that it can absorb the very signs of barbarism [the Irish

mantle with which Elizabeth is clad]28 into its scheme of civilizing

control" (29). Neill suggests that the portrait boldly appropriates

"the most threatening of all images of degeneration . . . the Irish

cloak of inscrutability, here emblazoned, however, with the signs of

her all-seeing power" (29). Moreover, Neill's reading proposes that

Elizabeth's "bridal locks present her as the spouse of her kingdom" and

that the "punning motto displayed above the rainbow of peace in her

right hand identifies her symbolic nuptials quite specifically with the

conquest of Ireland: Non sine sole Iris - `there is no Rainbow without

the Sun,' but also (since Iris was one of the ancient names for

Ireland, cited by Camden from Diodorus Siculus) `there is no Ireland

without her queen"'" (29-31). For Neill, the portrait's "political

agenda" anticipates "Mountjoy's imminent defeat of the most powerful

and obstinate of the Irish rebels, Hugh O'Neill, Earl of Tyrone, and

hence the final subjugation of Ireland" (31). The painting's

appropriation of the Irish mantle, "one of the great symbols of

cultural difference" emblematizes "the incorporation of a conquered

people into the body of the English nation-state" and is "a chilling

reminder of what it meant to be subjected to the inquisitorial

`perspective' of monarchical power" (31). The flip side of Neill's

reading, however, is that such an inquisitorial perspective subjects

the sovereign as well, her putative inscrutability and panoptic power

being dependent on the demonized Irish "other" who literally and

figuratively clothes her and gives her political and military

substance, while also symbolically embodying the spouse she never took.

The subversive potential of such a reading cannot be separated from the

admittedly more likely reading of absolutist self-affirmation proposed

by Neill. Nonetheless the potential for such an ambiguity remains

encoded in the portrait's images, just as the potential for challenge

to the sovereign's power is ever-present regardless of the panoptic

control exerted by the portrait "in the minds of potentially dissident

subjects" (Neill, 31). The polysemous coding at work in the image

articulates the symbolic contradictions embodied in the absolute

sovereign.

Whatever one's reading, then, whatever the intention

of the artist, the symbolism is acutely political, acutely ambivalent.

The religious connotations that cannot be detached from the rainbow's

iconography are no doubt in place, though not in an uncomplicated

manner. The canny manipulation of such imagery has as much to do with

political uses of religious symbolism as it has to do with the

monarch's control over her representation in portraits, that very

control being itself an exemplum of the monarch's power. The

possibility, discussed earlier, that such control has been supplanted

or challenged by the artist's manipulations indicates that the visual

resonances of the portrait have as much to do with the contestations,

mimetic and otherwise, to which power and its exercise are always

subjected as it has to do with the direct representation of an

unobstructed, unchallenged absolute monarch. Furthermore the painting

problematizes the relations between its visual and written texts, as if

to suggest that the contestatory interpretive possibilities generated

by the agglomeration of those texts parallel the contestatory political

contexts that surround the absolute monarch.29

It is not

unreasonable to suppose that Elizabeth, near the end of an extended,

unparalleled reign, would have had the temerity let alone the force of

personality to rescript traditional symbols in an autonomous manner

suited to her political purposes. This was the woman, after all, who in

an earlier time (January 1586-87) had written to James about his

mother, Mary Queen of Scotland, saying "let all men knowe, that princes

knowe best their owne lawes, and misiuge not that you know not" (Bruce,

43). The same letter refers to Mary as "the serpent that poisons me"

(42), and begs James to "[t]ransfigure yourself into my state . . . and

therafter way my life" (43). Though I do not mean to suggest a direct

linkage between Mary, the serpent, and the serpent found on Elizabeth's

left sleeve in the Rainbow portrait - the latter described by Strong as

an "attribute of Prudence and of the goddess Minerva" (1987, 159) - the

serpent image does have powerful connotations relating to the

ever-present threat of evil that calls for prudence, wisdom, and

perpetual vigilance on the part of the sovereign. Moreover, the serpent

has emblematic associations with "Intelligenza" in Ripa's

iconographical vocabulary, thus reinforcing the connections with the

earlier cited verses from Peacham's Minerva Britanna. The serpent, in

Ripa's emblem for "Intelligenza," "mostra che per intendere le cose

alte, e sublimi, bisogna prima andar per terra come fa il serpe" (260),

showing that to understand the sublime, one must first pass like the

serpent by way of the earth. Thus, the serpent emblematizes not only

knowledge of the sublime but also the ever-present physical realities

of earthly existence to which the sovereign is subject. The absolute

monarch links the exalted with the terrestrial and must negotiate the

symbolic space of each if she is to survive. The mediation of this dual

reality that informs the symbolic dimensions of the monarch's political

power is rendered in the image of the serpent.

Nor is the

serpent's appearance on Elizabeth's left sleeve accidental,30 the

sinister side having in Roman and Greek augury conflicting meanings,

both favorable and unfavorable. Thus, whether directly or indirectly,

whether intentional or unintentional, the portrait brings into play a

further symbol of ambiguity, one that poses in the manner of the

pharmakon both the threat of poisoning and the means by which that

threat can be avoided. The ambivalence has a notable political

function, especially poignant in light of Elizabeth's earlier cited

comments to James about Mary, and symbolizes both the threat to the

State with Elizabeth's sovereign body as target - and the means by

which that threat will be averted through the exercise of wisdom and

prudence. Visually balanced in the portrait's composition between good

and bad fortune, between the divine rainbow and the potentially evil

Edenic snake, the sovereign negotiates her way forward by virtue of her

capacity to shape representation, which at the same time poses an

ongoing challenge to her by virtue of its ambiguities or deliberate

falsehoods, symbolized in the snake, the colorless rainbow, the mask of

youth, and the cloak that not only masks Elizabeth's aged body but also

signifies her awareness of the duplicities by which she is surrounded

(thus necessitating the eyes and ears that serve her with

"intelligence"). The portrait, seen in such a light, takes on very

particular political resonances that play into both the fin-desiecle

and retrospective tones that may be discerned in it. Its conflation of

conflicting and ambiguous images represents the struggle to maintain

the illusion of autonomy in the face of an approaching personal

apocalypse beyond Elizabeth's control.

The capacity to shape

images - whether literary, visual, or musical, whether public or

private - has a great deal to do with the creation of an intelligible

mythography associated with the iconic display of power so crucial to

early modern absolutist ideologies. In the uncertain political contexts

prior to James's ascension to the throne of England in 1603 heightened

by the troubles in Ireland, the Scottish border problem, worries about

dynastic continuity, not to mention the failed Essex rebellion in

February 160131- the portrait served a powerful emblematic purpose in

reinforcing Elizabeth's political authority by way of her control over

imagery and her ability to make mimesis do her bidding, even at the

risk of exposing the ambiguities entailed by way of such a strategy.

Nonetheless, the portrait clearly visualizes the body of the Queen in a

manner that acknowledges her two bodies, one symbolic the other

corporeal, a concept that Ernst Kantorowicz calls "a landmark of

Christian political theology" (506). To deny or ignore the political

dimension of such a representation while affirming only the theological

is to evade crucial issues relating to how theology and politics were

inseparable constituents of absolutist ideology in early modern

England. The silent pageant of the portrait's personal and public

symbols, carefully watching and listening to its viewers, evinces

political will embodied in the interplay of its historical context and

its allegorical structures, all of which are profoundly intertwined

with the ideology of absolutist self-representation and

self-affirmation.

THE UNIVERSITY OF GUELPH

|

|

|

| 1 Roy

Strong places the painting within the "tradition of the Anglo-Flemish

studios" (1987, 161) and suggests either Marcus Gheeraerts or Isaac

Oliver as the most likely painters. For a more detailed account of the

several artists thought responsible for the painting, see Auerbach and

Adams, 60-61. The precise dating of the portrait is largely

conjectural, based on internal evidence from the portrait itself,

contextual iconographic evidence relating to the Queen's wardrobe,

personal iconography, and larger trends in European iconography, or

from circumstantial evidence surrounding the circumstances of

Elizabeth's appearances near the end of her life. Janet Arnold suggests

the portrait may have been "completed after the Queen's death [1603]"

(82) and that the portrait may originate in Elizabeth's "appearance at

a masque. . when she visited Sir Thomas Egerton, the Lord Keeper, at

Harefield Place in July 1602" (83). Mary C. Erler dates the portrait

"between December 6, 1602, the Cecil entertainment, and Elizabeth's

death on March 24, 1603, though a posthumous painting is not

impossible" (370). For additional information regarding the portrait's

possible genealogies, see Strong, 1985, 122. |

| 2 There

is "no precedent" for such an interpretation according to Strong, who

suggests instead a more secular interpretation based on the "chivalrous

context" (1987, 160) of the emblem. |

|

| 3 The

source of this allusion, as noted by Strong, is Cesare Vecellio's

Habiti antichi e moderni di Diverse Parti del Mondo (1593). Inigo

Jones's designs for the Masque of Blackness (1605) "based the masquers'

headdresses on one which Vecellio depicts for his Sposa Tessalonica.

Exactly the same source was used by the painter for the Queen's

headdress in the 'Rainbow' portrait" (Strong, 1987, 161). For some of |

|

| the visual sources of the Rainbow

portrait, see Strong, 1987, 158-61. |

|

| 4 Strong

proposes that 'the programme for this picture was drawn up by, or in

collaboration with, John Davies. The similarity to the imagery in his

Hymnes to Astraea (1599) was noted as long ago as 1952 by Frances

Yates" (1987, 157) and has been attended to more recently by Erler, who

reads the portrait as a "summarizing vision of Elizabeth's great reign"

(371). Graziani argues that "While we do not have any external evidence

to establish the programme as the Queen's own invention, I see nothing

that excludes this possibility" (259). |

| |

| 5 Elizabeth

W. Pomeroy, for example, argues that the portrait has "multiple layers

of representation and imagination" and goes on to state that "its

apparent signs may resist inclusion in an orderly internal system"

(73). Her focus on the Queen's wardrobe and patterns of dress, however,

almost completely misses those other more significant "layers of

representation" operative in the portrait. See also WJ.T. Mitchell's

assertion that "We can never understand a picture unless we grasp the

ways in which it shows what cannot be seen" (39). My reading of the

Rainbow portrait attempts precisely this task by way of the covert

ideological structures relating to absolutism on which the portrait

comments. |

|

| 6 Helen

Hackett reads the representations of Elizabeth's mask of youth, "seen

in numerous Hilliard miniatures and the Rainbow portrait," as "implying

that her sexual intactness had brought with it resistance to bodily

decay" (178). Such a resistance had obvious connections with the

association Elizabeth's image-makers strove to create between

immortality and chastity. The association enabled the myth-making

apparatus of absolutist self-representation, which Hackett reads as

having Biblical overtones: "Triumph over sexuality was interpreted as

triumph over the Fall, in turn enabling triumph over the penalty of the

Fall, mortality. Elizabeth's motto, `Semper Eadem,' `Always one and the

same,' came to signify not only constancy, integrity and singularity,

but also a miraculous physical purity and immutability" (178). The

political dimensions of such virtues cannot be ignored, especially in

reshaping the narrative context of the Edenic Fall, which ascribed to

Eve the blame for humanity's fall from a state of grace (Genesis 3).

Elizabethan images of the chaste queen figuratively rescript the

implications of the Fall by promoting sexual purity as the means to

overcome the mortality imposed by the consequences of Eve's actions. |

|

| 7See

also Louis Adrian Montrose's comments on the source for this statement

336, n. 26. Montrose offers a useful reading of the more obviously

political "Armada Portrait of Queen Elizabeth I" (George Gower?). aA

foreign danger," according to Montrose, "that heightens the collective

identity of Englishmen enables the Armada portraits to identify the

social body with the body of the monarch. An emphasis on the virginity

of that royal body transforms the problem of the monarch's gender into

the very source of her potency. The inviolability of the island realm,

the secure boundary of the English nation, is thus made to seem

mystically dependent upon the inviolability of the English sovereign,

upon the intact condition of the queen's body natural" (315). The

politics of representation are quite different, however, in the Rainbow

portrait. Inviolability is as much a function of the impenetrable mask

of youth that the artist imposes on Elizabeth, as it is of the eyes and

ears on the Queen's cloak that vigilantly guard and cover her body,

making that body symboli |

|

| cally

impervious to unknown threats. Gender seems to play less of an overt

role than does political expediency in the portrait's symbolism. Even

if one reads the eyes and ears as related to standard images of the

Virgin Queen, impenetrable because she is protectively cloaked by an

all-seeing, all-hearing intelligence, it should be remembered that

"Elizabeth's public self-presentation as Virgin Queen" was a apolitical

strategy, and one with considerable merit" (Levin 65). |

|

| 8 See Graziani, 255, and Strong,

1987,158-59. |

| 9 See,

for instance, James VI and I's argument in The Trew Law of Free

Monarchies, that "there is not a thing so necessarie to be

knowne by

the people of any land, next the knowledge of their God, as the right

knowledge of their alleageance, according to the forme of gouernement

established among them, especially in a Monarchie (which forme of

gouernement, as resembling the Diuinitie, approcheth nearest to

perfection, as all the learned and wise men from the beginning haue

agreed vpon)" |

| [ |

| (193).

Such a perspective, establishing the direct link between monarchic

government and the "Diuinitie' that it resembles, clearly represents a

form of political enablement through a transcendental, religious

signifier. |

| '10 See Foucault,

195-228. Foucault argues that "The body of the king, with its strange

material and physical presence, with the force that he himself deploys

or transmits to some few others, is at the opposite extreme of this new

physics of power represented by panopticism" (208). Foucault's reading

of the king's body invests overly in its material dimensions,

neglecting the more elusive textual and symbolic dimensions by which

the sovereign's body is disseminated and given meaning. In |

|

| fact,

the "new physics of power" predates both Foucault and Bentham,

Elizabeth's Rainbow portrait being a notable example of the

"heterogeneous forces" and "spatial relations" that Foucault associates

with that new physics (208). The composite nature of the Rainbow

portrait's symbolism in association with the spatial dimensions given

those symbols, especially in the relations of the portrait to its

implied viewers, make it a noteworthy expression of panopticism 's

"relations of discipline" (208). For a useful discussion of Foucauldian

theory in relation to "the disciplinary power of surveillance" in the

English Renaissance, see John M. Archer, 4-7. |

| 11 Mark

Breitenberg affirms that "The proliferation and popularity of emblem

books . . . allows us to realize the sixteenth-century perception of

the interconnectedness of pictorial representation, allegorical

tableaux and rhetorical figuration" (5). |

| [Footnote] |

| The

Rainbow portrait, with its extensive use of emblematic content,

reflects precisely such an "interconnectedness" between verbal and

visual texts as well as among different allegorical configurations that

promote notions of absolutist self-determination. Annabel Patterson, in

a reading of the Henry V quarto as a a "symbolic portrait" of

Elizabeth, states that "the eyes and ears on her mantle in the

'Rainbow' portrait... were a none-too-subtle reminder that the myth [of

"unqualified power and vitality"] needed the support of public

surveillance, that the cultural forms of late Elizabethanism took the

form they did because the queen and her ministers were watching" (4647.

|

| [Footnote] |

| 12According

to Yates, the "'Rainbow' portrait of Elizabeth at Hatfield House may

refer to some allegorical show in her honour at an Accession Day Tilt"

(103, n. 1). If in fact true, this would confirm the significance of

the political contexts of the portrait overlooked by so many of its

readers. For more on the Accession Day Tilts, see Yates, 88-111; Yates

argues that the chivalric code that the Tilts actualized had the

function, among other things, of "being a vehicle for patriotic

devotion to the popular national monarchy and zeal for the Protestant

cause" (109). |

| [Footnote] |

| 13 Nobuyuki

Yuasa calls the portrait "an enigma. . . when considered from the point

of view of allegory" (2), though her argument also allows for the

"political-socal symbols depicted in the lower part of the portrait"

(10). Andrew and Catherine Belsey affirm, more generally, that the

portraits of Elizabeth, aare elements in a struggle at the level of

representation for control of the state" (35). John N. King argues that

"the entire Gloriana cult was defined by the practicalities of

Elizabethan and Jacobean politics. Differentiation among the different

'cults' of the Virgin Queen demonstrates how the royal image was

fashioned dynamically by Elizabeth and her government from above, and

by her apologists and suppliants from below" (1990, 36). |

| [Footnote] |

| 14 Jacques

Derrida, in a discussion of Mallarme that resonates uncannily with the

Rainbow portrait's interpretive enigmas, comments that the meaning of a

fold "spaces itself out with a double mark, in the hollow of which a

blank is folded. The fold is simultaneously virginity, what violates

virginity, and the fold which, being neither one nor the other and both

at once, undecidable, remains as a text, irreducible to either of its

two senses .... But in the same blow, so to speak, the fold ruptures

the virginity it marks as virginity. Folding itself over its secret

(and nothing is more virginal and at the same time more purloined and

penetrated, already in and of itself, than a secret) it looses the

smooth simplicity of its surface .... It is divided from and by itself,

like the hymen" (258-59). Psychiatrist Elinor Kapp, in an extremely

unusual reading of Elizabeth as a young Princess, focuses on

Elizabeth's "folded lips" and the "set of her head on the neck . . .

[which] show a wariness that gradually as one studies the picture

becomes the most striking thing about it. There is a haunting |

|

| loneliness

about its reluctant but obsessive secrecy. No hint of laughter, of

relaxed pleasure, or of the delicious trial of innocent flirtation that

should be the inheritance of the pubertal girl, but a frozen

watchfulness that recalls to me countless victims of deprived or abused

childhoods" (308). Kapp's reading again points to the enigmatic fold

(the lips or mouth) that refuses us its secrets, while giving presence

to an ambiguous erotic charge. Christopher Pye, in a Lacanian reading

of the portrait, suggests that it "presents the erotic object as little

more than a breach" (69). To Pye, though the "slit-like eyes and mouths

seem to turn the cloak into the substance of flesh, these openings

nevertheless are explicitly only the lining of a fabric whose obverse

is seamless and unmarked. Through the wound-like organs, the body seems

to acquire an odd, hallucinatory reality" (68). Earlier on, Pye argues

that "if the portrait of the living queen had something of the death

mask about it all along, that is because the sovereign conveyed

absolute presence and power in an irreducibly divided and alien form -

as the profound vacancy of pure spectacle" (17). My own reading would

be that such a "vacancy" is more a function of the repressed

acknowledgment that power is contingent on spectacle, which is to say,

that absolute power is not so absolute after all. |

|

| 15 Strong

writes that the Privy Chamber was aa bridge between the public and

private aspects of the King's life. It was a room which could be

shifted in mood either way, towards the totally informal, or, on

semi-state occasions, with a swift mustering of its officers it could

easily become the scene of 'informal' formal receptions . . . the

monarch passed his time during the day and transacted most of the

affairs of state [in the Privy Chamber]" (1966, 32); see also 28-32.

For a comparative discussion of the Armada portrait of Elizabeth and

the Holbein portrait of Henry, see Andrew Belsey and Catherine Belsey,

11-14. John N. King presents a cautionary |

|

| reading

of Henry's codpiece as "no more than an item of conventional attire.

Codpieces appear with some frequency in portraits of Renaissance

royalty, nobility, and commoners" (1990, 59, n. 66). Roper argues that

the codpiece was the "issue [in the sixteenth century] which provoked

most explicit discussion of the male body . . . moralists like

Musculus, author of the Hosenteufel, condemned the codpiece not because

it paraded the phallus, but because it was a form of nudity. It

displayed the penis to lascivious eyes which would only too easily be

incited to lust" (117). 16Kng proposes that Elizabeth's "perpetual

virginity symbolized political integrity" (1990, 67). Hackett affirms

that "At the beginning of Elizabeth's reign there was already in place

a structure of sexualized iconography which was available to be

superimposed on the Queen as conventions of panegyric developed. It was

already |

|

| established

that the opposition between Protestant and Catholic, true and false,

could be forcefully represented by a polarisation of the female into

virginity or whorishness. Female sexuality was a focus of anxiety, and

was therefore able to carry many meanings" VO). According to Hackett,

during the early stages of her reign, Elizabeth "seems to have applied

the iconography of sanctified virginity to herself with more

seriousness than did her subjects" (71). |

|

| 16 Constance

Jordan suggests there is evidence Elizabeth "realized that a male

sexuality was an important (and even an essential) feature of a

monarch's power and that somehow she had to convey that in this sense

too she was figuratively male. Her virginity had somehow to include the

fiction of a male sexuality and the power it represented" (161). The

political dimensions of the Rainbow portrait clearly attempt to

articulate such a fiction. Leonard Tennenhouse argues that "The English

form of patriarchy distributed power according to a principle whereby a

female could legitimately and fully embody the power of the patriarch.

Those powers .... were no less patriarchal for being embodied as a

female, and the female was no less female for possessing patriarchal

powers" (103). The Rainbow portrait problematizes such a reading by

putting into question any notion of absolute gender categories through

its enigmatic mix of visual ambiguities. For Tennenhouse, "Elizabeth Tu |

|

| dor

knew the power of display" (102), and "in a system where the power of

the monarch was immanent in the official symbols of the state, the

natural body of the monarch was bound by the same poetics of display"

(105). But the power of display is also the power to veil the

significance of display. Veiling makes access to the monarch's

immanence "in the official symbols of state" extremely difficult to

achieve, thus insuring a measure of symbolic autonomy to the sovereign

in the face of the perpetual gaze of her subjects. John N. King has

further suggested that the historiography of Elizabethan iconography

involves a blend of "the iconography of late medieval queens as well as

a carefully orchestrated manipulation of the doctrine of royal |

|

| supremacy

by the circle of courtiers, writers, artists, and preachers who

operated under the aegis of Henry VIII and Edward VI. The biblical

style of Reformation kingship dominates the early iconography of the

reign of Queen Elizabeth prior to its eclectic infusion into her

veneration as a classicized virgin: Astraea, Diana, or even the Roman

Vestal" (1985, 84). The conflation of such diverse symbolic elements is

partially accounted for by the degree to which Elizabeth's gender

complicated her relation to the traditions of absolutist political

symbology. King argues that Elizabeth's virginity compounded "an

already difficult political problem" and that "apologists adapted late

medieval iconography, which hailed queens consort as intercessors with

imperious husband-kings, to offer instead emblematic variations that

praised Elizabeth as a powerful monarch who could govern in the absence

of any consort" (ibid., 42). |

| 17 see Barthes, 25-27. |

|

| 19Archer

links Foucauldian notions of sovereignty with precisely such a scopic

dynamic between the observer and the observed, the sovereign and the

subject: "The culture of display that Foucault associates with the

concept of sovereignty was supplemented by a corresponding culture of

observation and surveillance in which sovereignty and intelligence were

bound pragmatically together" (6). |

| 20Allison

Heisch notes a "direct correlation between the political insecurity of

[Elizabeth's] position and the often deliberate obscurity of her

language" (32). Representational ambiguity had its obvious political

uses, whether in visual or textual |

|

| terms,

especially in relation to promulgating the illusion of the queen's two

bodies ("I am but one Bodye naturallye Considered though by his [God's]

permission a Bodye Politique to Governe" [cited in Heisch, 33]), itself

dependent on the fiction of divine authorization. Andrew Belsey and

Catherine Belsey comment on how, as "the Queen's iconic character is in

the process of construction," her body became "more or less

indecipherable" (20). In a series of portraits attributed to John

Bettes [the Younger], she has become pure geometry" (ibid.).

Indecipherability and elusiveness characterize the representation of

Elizabeth's body in the Rainbow portrait, perhaps providing further

evidence in support of Francis Barker's notion that "the body has

certainly been among those objects which have been effectively hidden

from history" (9-10). |

|

| 21According

to Arnold, the garment may have been "specially designed for a masque"

(82), the theatrical display of the eyes and ears thus taking on a

further allegorical dimension in the public sphere of representation

that the masque embodied. The queen publicly incarnates political

vigilance itself and the representation of that vigilance, as if to

suggest that there is no room for the split between the signifier and

signified in the construction of absolute representations of monarchic

self-affirmation. Arnold also notes that "the Queen did have other

clothes embroidered and |

|

| stained

with similar motifs" (82). See also Archer's discussion of Ripa's

emblem for the spy, "a man 'vestito nobilmente' in a cloak covered with

eyes, ears, and tongues |

| . . the

eyes and ears on the cape [in Ripa's words] `signify the instruments

with which spies exercise such arts to please their Lords and Patrons"'

(4). Archer states in a reading largely derived from Strong, that the

"painter of Elizabeth's Rainbow portrait took up the eyes, ears, and

tongues motif for the mantle that the queen wears, probably to indicate

. . . the many servants who provided her with intelligence" (4). Such

intertextual and intervisual allusions produce a sophisticated texture

of political, religious, and erotic inflections that make it difficult

to reduce the symbolic content of the portrait to a simple system of

one-to-one correspondence between the symbol and its referent. |

|

| 22For further references to Hawkins's

use of the rainbow in relation to the Virgin Mary, see Diehl, 171-72. |

|

| 23King

affirms that "It is undeniable that Elizabeth's retention of virginity

constituted 'a political act' and that the celebration of her

remoteness from erotic love played an important role during her reign"

(1990, 30-31). The use, however unusual or unlikely, of Marian

symbology in the Rainbow portait may serve to reinforce the divine

linkage that authorizes Elizabeth's absolute power, while supporting

the politics of her virginity as wholly defensible given the Scriptural

example of the Virgin Mary. |

|

| 24Again,

the painting hints at aesthetic practices that fall outside of

conventional representations, Strong arguing that "the ethos of the

Queen's portraits" was one in which athe standard ingredients of

Renaissance painting, chiaroscuro and both linear and aerial

perspective had yet to be received or understood" (1987, 44). A further

possibility is that the lack of color in the rainbow is due to fading

or chemical changes in the pigments used to paint it. To my knowledge,

no evidence exists to substantiate such an hypothesis. Furthermore, in

order to support the faded rainbow hypothesis, one would then have to

explain why the other colors of the portrait have remained so

well-defined. |

|

| 25This

observation would be at direct odds with Frye's suggestion that 'Both

the illumination of her face and chest and the inscription 'Non sine

sole iris'. . . make clear that Elizabeth represents the sun" (101-02).

The ambiguity arising from how to read the portrait's framing of the

relations between its figurative sun and rainbow must be understood

within the general historical context of Elizabethan or Tudor

portraiture, one in which there is little likelihood that the painter

would reveal, in any way accessible to the royal sitter or the

contemporary viewer, a subversive image. As Strong points out, "In the

Tudor period royal portraiture was controlled by the use of approved

images. The control broke down from time to time as in the 1590s when

portraits of Elizabeth depicting her as old and therefore vulnerable. .

were destroyed by order of the Privy Council" (1985, 122). Nonetheless,

the very |

|

| ambiguity

regarding the provenance and dating of the Rainbow portrait point to

the potential ambiguities in how it is to be read. If the portrait was

posthumous or painted extremely late in Elizabeth's reign, as is most

probable, then the degree to which symbolic control over the portrait's

images may have been effectively enacted could have been subverted. The

relativism of readings that give rise to interpretive ambiguities

depends on the degree to which one attributes iconic significance to

disparate elements of the portrait. If one makes a further interpretive

shift and reads the portrait as dissimulative rather than allegorical,

a very different symbolic structure |

|

becomes

apparent, producing different cues for reading, different implicit

constraints on interpretation, and ultimately a different kind of

ambiguity than the one produced by more conventional interpretations.

In a sense, my reading, by placing the portrait in a different context

from the one in which it is customarily viewed, also implies that the

portrait creates its own context and hence different rules for reading

its assemblage of images. Mary E. Hazard states that the "portraits

which represent the qualities of the subject (Ermine, Sieve and

Rainbow), that is to say, those portraits which might be described as

representing the genitive of quality or description, are the most

problematic to interpret - partly, as we have seen, because of the

contextual ambiguity of the inflection: the ambiguity of relationship

between picture and text, often a recherche source; the ambiguity

intended by a political subject, patron, artist, or some combination of

these. Such pictures were probably as difficult to interpret for

Elizabethans as for us" (79).

26 Cited in Kantorowicz, 438. |

|

27The

association of sovereign power with light is a commonplace absolutist

topos. In Eikon Basilike, for instance, published within hours after

the death of Charles I on 30 January 1649, light figures as a

retrospective and nostalgic metaphor for the political and symbolic

order that will have been lost after his execution: "Happily where men

have tried the horrours and malignant influence which will certainly

follow My enforced darkenesse and Eclypse, (occasioned by the

interposition and shadow of that body, which as the Moone receiveth its

chiefest light from Me) they will at length more esteeme and welcome

the restored glory and blessing of the Suns light" (74). The

encroaching shadows of the Rainbow portrait may well prefigure the

"horrours and malignant influence[s]" that posed an ongoing threat to

the stability of absolutist claims to political power.

28 Identified as

such by Arnold in Queen Elizabeth's Wardrobe Unlock il, 81. |

|

| 29In

this last regard, Leonard Barkan observes the need "to question the

assumption that a picture's caption or its verbal narrative exists in

the same discursive space as the picture itself; on the other hand, we

have also been forced to notice that even the most non-narrative images

exist in a verbal nexus" (330). |

|

| 30 In

Ripa's emblem for "Intelligenza" the serpent also appears on the left,

Ripa taking pains to indicate which symbol appears on which side of the

emblem: "nella destra mano [Intelligenza] tenga vna sfera, e con la

sinistra vna serpe" (259; see fig. 5). |

|

| 31 See

the Belseys' brief summary of the political circumstances Elizabeth

faced near the end of her reign (33). They argue that "Elizabeth's

control, especially in the later years of her reign, was in practice