Kyaiktiyo, 160 km southeast of Yangon. Despite

the bfl colic setting deep in the hills, the settlement

bustles with people well after 8 p.m.

OF NEW BRIDGES AND CLOSED CAMPUSES

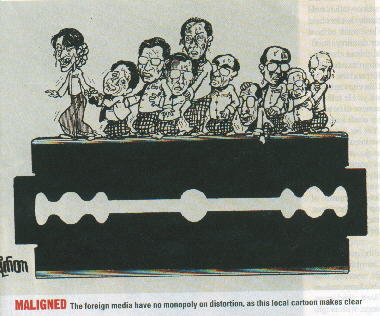

I have also heard that there are travel restrictions

for

journalists. I soon discover that this is another

canard. When I tell the regime's main spokesman

Col. Hla Mim that I plan to travel outside of Yang-

on, he says: Go where you want. If you need a

visa extension, let me know."

I decide to hire a car and driver and visit the

former capital Mawlamyine, a small port city 120

km south of Kyaiktiyo. We leave at 6 a.m., quick-

ly clearing the almost empty streets (Yangon is a

slow-starting city). The journey takes seven hours,

and we do it with only one short break. The road

is fine as far as Bago, then it deteriorates a little,

then improves again - although remaining nar-

row. I see no other Caucasians during the whole of

this trip, so I am bemused when, halfway to Maw-

lamyine, we pass a large sign in Burmese and

English that says: Please give all assistance to

international travelers."

But it is surprise rather than bemusement that

I

feel when, in the final stretch, we pass over a cou-

ple of new suspension bridges, obviating the need

to take the old car ferry at Mottarna. Painted a pas-

tel orange shade, they are long and sleek, and again

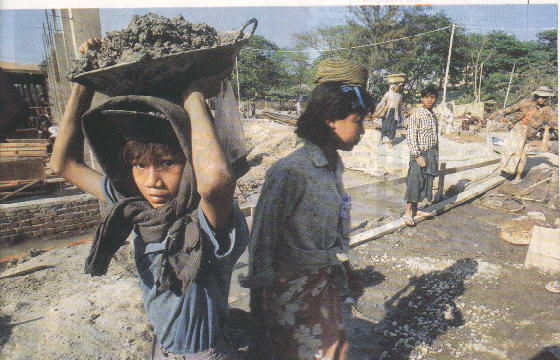

beg the question: How do they do this? Forced

labor'? Surely not for such skilled engineering

work? Certainly, the regime denies it; although

Burmese exiles claim it continues. All I can say is

that on my travels, the various road crews I see are

invariably military men not civilians. On the drive,

we pass squads of uniformed conscripts doing

maintenance work and clearing the verges.

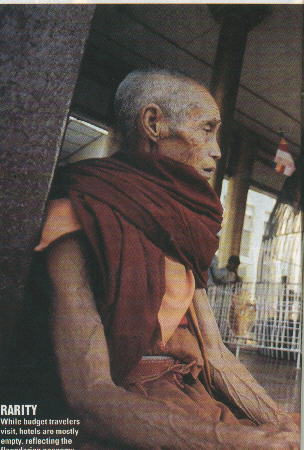

As for Mawlamyine itself, I suspect Kipling

would find it little changed. They still smoke

whacking white cheroots and the temple bells still

call. Down in the sidestreets around the jettys,

however. it is not so nice. There is an overpower

mg air of desolation and squalor, only marginally

mitigated by the silent dignity of the people. Yet

the bounty of produce in their market is astonish-

mg: meat, fish, rice, fruit, vegetables and wonderful

arrays of

fresh flowers. People buy big bunches of them! It is

hard not to

feel optimistic surrounded by flowers. But before I get too in-

toxicated. I decide to visit the local university.

Perhaps the most telling thing about Myanmar is that the

campuses remain closed. Even Foreign Minister Win Aung

looks sad when he talks about this. And frankly it is an area

where the regime has been less than honest. Last year, I was as-

sured that the universities would reopen soon. some depart-

ments have, but by and large most are still do not. The cam-

pus of Mawlamyine University, a relatively new building, is in

utter neglect. Lecture rooms are untouched since they were pad-

locked three years ago. Moldering papers and specimen jars

gather dust in musty rooms. The quadrangles are littered with

the ashes of open fires and dog exereta. The regime can talk all

it likes about securing ceasefires with rebellious minorities, but

if it can't risk opening the universities to allow its youth to get

an education then there is no real stability.

NE WIN'S GUN-PACKING GRANDSON

One evening in Yangon, I unwittingly refute the assertion

that

the military police check residences for unauthorized

guests