By the end of his life he had matured into an astute, thoughtfil statesman with a strong abhorrence of fascism and a deeply rooted belief in democratic values. His vision encompassed an "internationalism of creative mutuality" which would bring "abiding peace, universal freedom and progress." He foresaw that time and space would be conquered and that we would become a world of "immediate, not distant neighbors." He envisaged a "new Asian order" to build Asian unity and co-operation, and win freedom, security, peace and progress for the world.

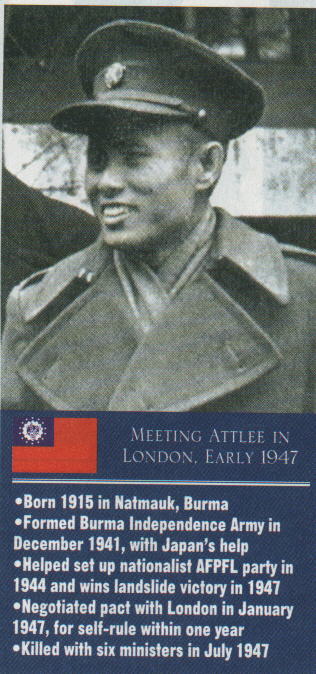

Born in 1915 to a solidly respectable family in a small town in central Burma, my father was a simple person with a simple aim: to fight for independence. But that single-minded drive took him along a complex path. Though he was an outstanding schoolboy, after joining Rangoon University he began to neglect his studies for politics. He was a moody young man, taciturn and garrulous by turns, indifferent to social niceties. His close friends, however, spoke of his warmth; only his shyness made him ap- pear stern and aloof to those with whom he was not at ease.

After becoming President of the All Burma Students' Union, my father gradu ated to the activism of the Dohbama Asiayone an organiz tion of young men more aggressively nationalist than earli generations of Burmese politicians. However its members the thakins, worked closely with some older counterparts in estal lished parties. Through these contacts, my father left Burn clandestinely in 1940 to seek help. The original plan had been to approach the Chinese, but it was with the Japanese that ir father negotiated a military training program for 30 your Burmese men. This was the birth of Burma's armed forces.