COUNTRY IN LIMBO

In Myanmar it is not safe to assume anything, especially about politics

BY ROGER MITTON YANGON

It's about six point some- thing," says Kyaw Kyaw Maung, governor of the Cen- tral Bank of Myanmar. Pres- sed for the official dollar exchange rate of the kyat, he point something, six poin something." Deputy finance ministe Brig.-Gen. Than Tun echoes the governor. Neither care to be too specific about the unofficial exchange rate (more than 300 to the dollar), the level of foreign reserves or even the inflation rate.

The vagueness, from men who shoul know instantly and exactly such cruci2 statistics, characterizes Myanmar 50 year after Independence. Nothing is definitc everything is open to interpretation. Con fusion can be found everywhere in thi resource-nch but desperately poor natior 'Never assume anything," says Mauri Drew, country manager for Asia Pacific Energy Co. "Nothing is quite what it seems.

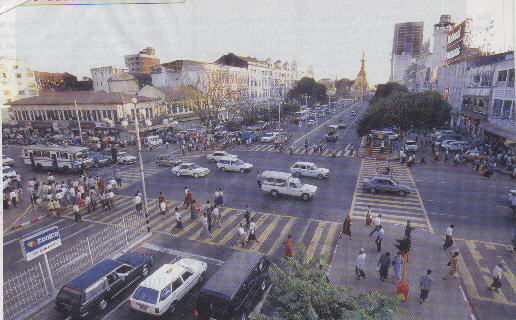

Security has improved, although an- tagonism among the minority ethnic groups toward the majority Burmans still exists. Planes flying into Yangon are often full. But in the capital, many restaurants and bright new hotels appear empty. Cen- sorship is rigid; yet ubiquitous satellite dishes beam in world news in real time. Despite economic hardship, sidewalk mer- chants are busy and the streets arc jarnmed with traffic. The quality of roads is better than it used to be, but even First Secretary talin Nyunt said recently that "Myanmar's infrastructure is far behind the times."

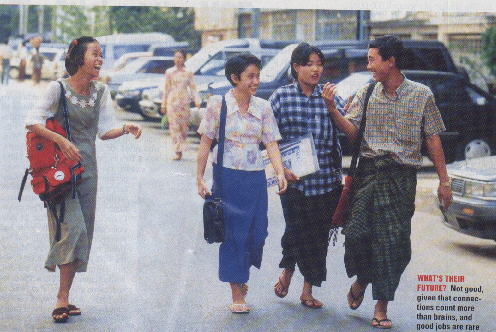

Schools have so few resources that most parents pay for extra private tuition for their children. Says a top civil servant: "The education system is really very sick.' Yet the level of spoken English is better than in neighboring Thailand. Universities': have remained closed since student pro- tests in December 1996 (see story pagc 23). But "in the very near future the univer- sities will re-open," says cabinet minister Gen. David Abel.

In a country where even tertiary edu- cation is uncertain, it is no wonder that people glean whatever information they can from whatever clues are available. There is so little transparency, and so much obfuscation and dissembling, that no one is ever sure of anything. This is certainly the case when it comes to explaining the recent changes in the military government.

On Nov.15, Myanmar's State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC), a group of generals who had ruled since 1988, was replaced by a State Peace and Development Council. Some top-ranking generals were sacked and several have been detained while under investigation for bribery. The cabinet - which adminis- ters the decisions of the Council - was also revamped. The makeover is not just cosmetic. "Definitely not." says one senior envoy. "It is very substantive." But what does it mean and why did it happen now?

Some suggest reclusive former dicta- tor Gen. Ne Win, who stepped down

in 1988, told Khin Nyunt it was time to act;

|

|

but, as usual, this is disputed. Minister Abel gives the official line that SLORC had completed its task of restoring law and order. "Everything is about 95% peaceful now," he says. "So we can take a further step forward to bring peace and development. That's why we changed." Actually, there were other reasons. Namely, to get rid of that reviled acronym SLORC, to remove several flagrantly corrupt ministers, and to try to reinvigorate the process of government. In attempting to do this, the roles of the new 19-menihes Council and the 41-member cabinet have been clearly delineated for the first time.

The country is effectively run by five Yangon-based generals: Council chairman Than Shwe, vice-chairman Maung Aye, and secretaries 1, 2 and 3 Khin Nyunt, Tin Oo and Win Myint. They comprise Myanmar's so-called politburo, and they are the only ones who hold positions in the Council and also sit in on cabinet sessions. The other 14 Council members are the regional military commanders. Since most of these are based far from Yangon, it is likely the whole council will meet just three or four times a year.

The new line-up may improve effi- ciency. Says one regional commander who is a new council member: 'In the past, ministers sometimes never responded to our requests. Now, if there is a problem with a minister, we can go straight to Gen. Than Shwe who promises an answer in 24 hours." Since many new ministers are for- mer commanders of similar rank and age as their replacements in the field, there is greater rapport between Yangon and the regions. "[The changes have brought more effective decision-making," says a Western diplomat "The officials are more account- able to each other." New regional comman- ders and ministers are also supposed to be more responsive to the minorities and fol- low through on government promises of economic development in their areas.

The changes were also part of an anti- corruption push that led to the downfall of the ministers of commerce, tourism, agriculture, forestry and transport. Says Tin Tun, the deputy energy min- ister: "A lot of people who were found guilty of corruption have been jailed. You have to keep a check on everybody." Another military leader told Asiaweek: "We are doing a kind of house-cleaning. Investigations are going on and we'll await the out- come." More than 40 top officials are being probed. Some believe that sec- retary-2, Lt.-Gen. Tin Oo, National Planning Minister Soe Tha, and Yangon Mayor Ko Lay may be under investigation but officials deny this.

The new arrangement also means that the five-member "politburo" who attend Thursday morning cabinet meetings will have a relatively free hand to over- see the affairs of state. The five have dif- ferent degrees of power. Who really runs Myanmar from among this group? Says an Asian diplomat: "It's more than one, less than five." Many speculate that intelli- gence chief Khin Nyunt and armed forces head Maung Aye call the shots, with Than Shwe balancing the two.

The changes have restored Khin Nyunt (or S-l as he is universally known) to a dominant position. Many new ministers and commanders are more comfortable with the pragmatic, reform-minded S-I than with the conservative. hold-the-line.

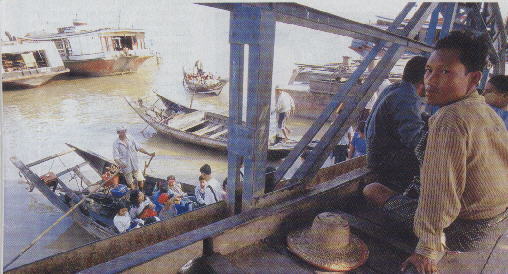

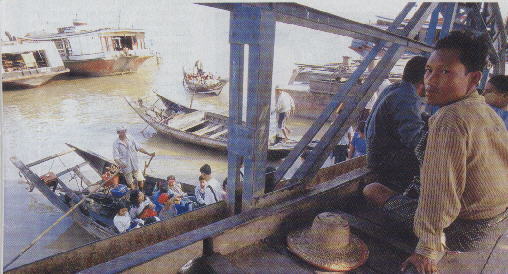

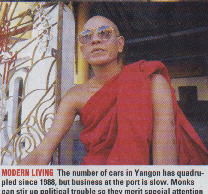

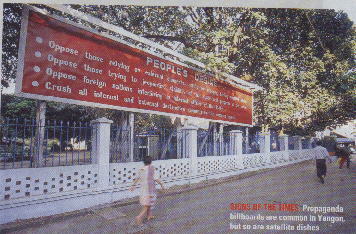

MODERN LIVING

The number of cars in Yangon has quadru- pled since 1988, but business at the port is slow. Monks can stir up political trouble so they merit special attention .

Five Who Call the Shots

Lt.-Gen. Khin Nyunt. At 58, the thin-lipped Secretary-i of the ruling Council (known as S-I) appears to be the top man for affairs of state and poli- cy-making. Still sometimes derided, however, as "the little guy under Ne Win." Charming, intelligent, wry sense of humor, excellent English, but shy and cautious with strangers. Intelli- gence services head since 1983. Seen as robustly anti-corruption. Weakness: no real power base among active army units, which may be fatal to his vision to open up Myanmar. Likes to read. Avoids pork and beef, and every Mon- day goes strickly vegetarian.

Gen. Maung Aye. Council vice Sketches of the strongest of the strongmenMyanmar is ruled by a 19-man State Peace & Development Council In truth five members run the show, perhaps guided occasionally by former ruler Gen. Ne Win The power quintet:

chairman and, more importantly, head of the armed forces, the single most im- portant job in the country. Charmless hut respected by fellow officers and liked by ordinary grunts. Admired for holding together the army's many fac- tions and often recalcitrant regional commanders - and for making sure its budget is not cut. In his early 6()s.

Senior Gen. Than Shwe. Council chairman and head of state. On paper, the most powerful man, but in reality seen as a portly father figure whose main role is to balance the Khin Nyunt and Maung Aye factions. Genial and speaks good English. Now 65, he tires easily, though rumors of his quesfion- able health are overstated.

Lt.-Gen. Tin Oo. Secretary-2 of the Council. In his 60s, Tin Oo is aligned with the more dogmatic Maung Aye camp. Last year he was the victim of at least one assassination attempt. In April, his daughter was killed by a let- ter bomb intended for him, and rumor has it that in December he received a light flesh wound from a gun attack at his home. Tainted with allegations of corruption, partly due to opulent life- style of family and partly due to the at- tempts on his life - which some feel may be from businessmen whom he has crossed.

Lt.-Gen Win Myint. Secretary-3. Cheery and plump. Has retained his powerful post as adjutant-general, which gives him clout to control ap- pointments in the military. Avoids limelight, but is regarded, aside from his soulmate S- 1, as the brightest man in the top five. In his late 60s.

Maung Aye (who is said to take a dim view of Khin Nyunt' 5 support for dialogue with certain elements in the National League for Democracy). But Khin Nyunt is seen as a "white collar" officer who cannot rally the battle-hardened veterans under Maung Aye. As one diplomat says: "Maung Aye may be charmless, but he's effective. He's a good soldier, and he keeps the armed forces together." However, Maung Aye's poor English and lack of an international per- spective mean he can never represent the new, more outward-looking, market-orient- ed Myanmar that was inducted into ASEAN last July. "There has been a change in atti- tude since it became a member," says a senior Thai foreign ministry official. "The government is more trusting."

Many say the military's greatest con- cern is not the NLD, 'volatile students or moody monks (who may reflect public discontent), and certainly not criticism from the West, but rather a split within its own ranks. But talk of divisions has quiet- ed. Says a senior officer in Khin Nyunt's new think-tank, the Office of Strategic Studies: "It is wishful thinking. We have a collective leadership, and while there may be differences, once a consensus is reach- ed, all will back it up."

Whatever their differences, Maung Aye and Khin Nyunt need each other and need the dull but steady Than Shwe for balance. Of this key trio, it is Khin Nyunt who is most visible. Every day the govern- ment-run newspaper, New Light of Myan- mar, carries numerous pictures of S-l opening health centers, welcoming digni- taries, inaugurating new bridges - and, most prominent, meeting religious leaders. The monks are deeply respected in predom- inantly Buddhist Myanmar and keeping them content is a major preoccupation of the junta. Says a diplomat: "The generals meet the people all the time. They are not aloof." Minister Abel says: "The military is very popular with the people."

Not all agree. Complaints about the junta's performance abound. Forced labor and 116,000 refugees along the Thai bor- der bring shame to Yangon. The economic upswing - GDP growth averaged 7% for the past five years - has tailed off. Inflation is officially 26%, unofficially about 3~%. Even Khin Nyunt has said that the country "is weak in foreign exchange savings and reserves." Tourism is down. More important, so too is the rice harvest. This year no rice will be exported to con- serve stocks for domestic use and prevent possible unrest. Still, Central Bank Gov- ernor Kyaw Kyaw Maung says: Things overall are quite good, not bad. Why all the complaining?"

Oppositionists could tell him. In December, several NLD members were

A Man of Some Influence

What Ne Win wants may still matter

Although he officially stepped down amid growing turmoil in 1988, Myanmar's former dictator, Gen. Ne Win, 86, continues to cast a shadow over the country. Did the reclu- sive Ne Win really order the current mil- itary junta to make last November's dra- matic changes? Says an Asian diplomat "The jury is still out on that." The gener- als themselves deny it. Cabinet minister Gen. David Abel says: "He is a man of very clear decision. When he left, he just got up on the stage and said, 'I am responsible for what is happening and I'm out. Thank God, I've turned my back on politics."'

Others disagree. Says another dip~ lomat: "He's involved, definitely" Some say he should become more in- volved and suggest he promote a rap- prochement between the NLD's Aung San Suu Kyi and the junta. Says a top civil servant: "Everyone hopes he can bring Khin Nyunt and Suu Kyi together, since he is close to S-1 and he knew her father." Military men dismiss the idea.

Just who is Ne Win? He was born in a town north of Yangon to an ordi- nary family. His real name is Maung Shu Maung but, like other independence fighters, he adopted a nom de guerre; "Ne Win" means "bright sun." While working as a postal clerk, he was swept up in the fight for freedom. Ne Win came to power by force in 1962 and ruled with an iron fist for 26 years.

Economic problems led to wide- spread unrest in 1988 and by July the general stepped down. Many wish he had done so sooner. Says Ba Thaung, a former U.N. ambassador: "He has always been a very stubborn man.

And one unbothered by conven- tions. The number of his wives is a rnat- ter of jovial conjecture - most say between four and six. His second and most influential wife was the American- educated Khin May Than. They had three children, including his favorite daughter, Sandar Win, a hotelier and powerfal figure in Yangon.

Last September, Ne Win visited his old chums, Singapore Senior Minister Lee Kuan Yew and Indonesia's Pres- ident Suharto, both of whom reportedly complained about the rampant bribery in Myanmar. Afterward, Ne Win told Khin Nyunt that corruption had to be rooted out. So it came to pass on Nov.15.

It may well have happened. Even if it didn't, the generals may not mind the rumors. They prefer the military to believe that Ne Win has approved, if not directed, their more portentous decisions. Such is the wily old dicta tor's clout these days.

given lengthy jail terms in what many view as an ongoing political witchhunt. The movements of NLD Sec.-Gen. Aung San Suu Kyi remain severely circumscribed. Sitting at the dinner table with his family, a Yangon businessman says: "Suu Kyi is still very popular, 95% of the population is behind her. I am optimistic change is com- ing. These men are leading us nowhere." Miriam Marshall Segal, chalr of Myanmar Business and Trade Consulting, Inc., dis- putes this. Says she: "They are doing good for the country, and I don't think anyone else could do it better." At least the generals have abandoned doctrinaire socialism and are working toward multi-party elections. Slowly. Says Deputy Energy Minister Tin Tun: "Let me say very clearly our population still needs a lot of political education." When the time does come, the generals will not bow out entirely. Says one officer: "In the new Constitution there [will be] a clause saying the military should play a leading role in national politics." Following the Indonesian model, a quarter of the seats in parliament will be reserved for the armed forces.

Exiled pro-democracy lead- er Ba Thaung, the country's for- mer U.N. ambassador, scoffs at the notion. "Indonesian-style democracy will not work in Myanmar," he says. "Without a negotiated political settlement, the country's problems will never be solved." He points to the astonishing turnout and result of the 1990 elections, which saw Suu Kyi's NLD sweep 80% of the seats. But the military insists that it must have a presence to ensure the nation's integrity. "We will be a stabilizing body," says one officer.

Democracy, Myanmar-style, may not quiet the critics though. And that rankles. Says Lt.-Col. Hla Min of the Office of Strategic Studies: "We are a soft target. Sanctions are imposed on us, while other countries in the region where there are human rights abuses and no elections are given most favored nation status."

The government likes to point out that France, Holland, the United Kingdom and the United States are among Myanmar' 5 biggest business partners. One senior offi- cer murmurs: "The hypocrisy is astonish- ing." Sitting at home, deprived of power even though her party won a landslide elec- tion victory eight years ago, Suu Kyi might say the same about the military's claim to be moving toward democracy. Both sides plead sincerity. Confusion and contradic- tion. Modern Myanmar.