Mythology and Ideology in Italian Renaissance Art

The origins of the Renaissance should not be identified solely with

the revival of interest shown by European civilization in the art and

culture of Classical Greece and Rome. More properly, the renewed interest

in Classical learning should be considered a reflection of a more significant

rebirth that took place at the end of the Medieval period.

During the Medieval period, there were two focal points to European

society: feudalism and the Church; the first to govern the material world,

the second to govern the spiritual world. Both feudalism and the Church

were highly-structured and rigid systems, intolerant of change, and both

clearly supported the proposition that the rights of the individual be

subordinate to the rules of society.

The thing that eroded the power of these institutions, and was central

to the Renaissance, was the rebirth of the individual in society. For

the artistic tradition, the most important aspects of the Renaissance

were the rise of powerful, independent city states and the development

of Franciscan humanism....

It was in southern Europe, particularly in central and northern Italy,

that this began. The rise of independent city states such as Florence,

Milan, and Venice provided the economic circumstances that could support

the new Renaissance artists.

The transition from a feudal economy to city-based commercial communities

was easiest in Italy because feudalism never achieved the dominance there

that it reached in the rest of Europe, and the new wealth produced a more

sophisticated and civil-minded citizenry, which in turn created a demand

for new and different entertainments. J. H. Plumb put it this way:

"Culture was constantly extended, thereby creating opportunities

for advancement for those without the privilege of birth or the security

of wealth. The gradations in society increased as well as thickened: individual

enterprise, creative imagination, and the weight of temperament became

of great potential value in a world in which the lines of class structure

grew blurred." 1

The new creative artists supported by the civil patronage of the Italian

city states searched for ways in which to express their new freedom. Franciscan

humanism provided one such way in its newly-revived sense of enjoyment

of nature and natural beauty ... so different from the denial of the world

fostered by the medieval Church's asceticism.

The influence of the Franciscan movement can be seen as early as the

Giotto frescoes in the church of St Francis at Assisi, but the Franciscan

movement did not indulge in much philosophizing over nature, and the emerging

Renaissance culture demanded a more objective appreciation of the world.

This was found in the revival of interest in the culture of the ancient

world.

Renaissance humanism did not, however, spring fully grown from Classical

philosophy. It emerged over a period of over a century as a fusion of

Christian and Classical thought.

Typical of the early Renaissance Humanists was Leon Battista Alberti

(1404-1472), who was at the same time an artist, philosopher, architect,

and mathematician. His attitude to the wisdom of the ancients, and to

its combination with Christianity, was primarily pragmatic and rationalistic

- his Humanistic religion rejected most of the mystical overtones of contemporary

Christianity.

Where Alberti is the direct forerunner of later Renaissance Humanists

is in his ideas on beauty, drawn from Plato's Classical theories on love,

beauty, and the nature of the universe. Alberti insisted that beauty has

objective reality, and is not dependent on mere subjective opinion.

Where he differed most strongly from the later Humanists ('Neoplatonists'

as they came to be known) was in his refusal to indulge in abstract speculation

on his ideas. "Everything is attributed to reason, to method, to

imitation, to measurement; nothing to the creative faculty."

2

During the second half of the fifteenth century, his rational, almost

scientific, philosophy of art fell out of favour among the intellectuals

in his home city of Florence, which was then the centre of the Italian

Renaissance. By that time, Humanism had turned to a more mystical interpretation

of Classical learning.

An example of the difference appears in the interpretation of Plato's

theories on love: where Alberti considered love primarily in relation

to its social function, the Neoplatonists regarded it to be the contemplation

of divine beauty.

Considerable philosophical thought went into this concept, including

ideas on the four Platonic states of being, celestial and natural love,

and so on, but the elaborations involved have only peripheral application

to Neoplatonist art of the period.

In art, these Neoplatonist ideas were translated into allegorical and

symbolic images: images drawn from pre-Christian mythology, and interpreted

as symbols for concepts acceptable to Renaissance Christians. Initially,

the artists (Botticelli is perhaps the prime example) were content to

depict fairly straightforward analogies. In the case of Botticelli's work,

this attitude can be found in a number of paintings. I will refer primarily

to two of his works: Venus and Mars and Primavera (='Spring').

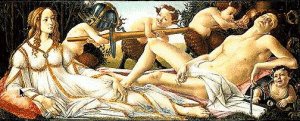

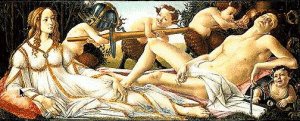

The origin of the Venus and Mars is directly from

Classical myth. The scene depicted is of the divine couple just prior

to their discovery by Vulcan, Venus' husband, but the concept illustrated

has little to do with marital triangles, but is instead a visual corollary

to a commentary on one of Plato's works by Marsilio Ficino, leader of

the Neoplatonist revival in Florence.

The origin of the Venus and Mars is directly from

Classical myth. The scene depicted is of the divine couple just prior

to their discovery by Vulcan, Venus' husband, but the concept illustrated

has little to do with marital triangles, but is instead a visual corollary

to a commentary on one of Plato's works by Marsilio Ficino, leader of

the Neoplatonist revival in Florence.

Ficino's commentary in part reads: ". . . Mars is outstanding

in strength . . . because he makes men stronger, but Venus masters him.

Mars never masters Venus . . ."

3

Stripped of its mythological overtones, the painting can be interpreted

as a glorification of 'cosmic love' (Venus) pacifying the violent material

universe (Mars).

The second of Botticelli's works discussed here also

has love as a central theme, though the symbolism is less readily apparent.

The Primavera seems cluttered: there are eight major figures (excluding

the Cupid, which is included primarily as part of the standard Venus/Cupid

couplet, and all can be identified with characters out of Classical mythology.

The second of Botticelli's works discussed here also

has love as a central theme, though the symbolism is less readily apparent.

The Primavera seems cluttered: there are eight major figures (excluding

the Cupid, which is included primarily as part of the standard Venus/Cupid

couplet, and all can be identified with characters out of Classical mythology.

On the right there are three figures – Zephyr, Chloris and

Flora – symbolizing the coming of Spring and, by extension,

the beauty of the natural world. On the left, the figures symbolize the

mind and spirit: Mercury, the messenger of the gods, here stands for reason,

and the three Graces (Aglaia, Euphrosyne and Thalia) are symbols of the

refined pleasures of life. The central figure of the painting, both literally

and figuratively, is Venus, representing the meeting point of both Natural

and Spiritual principles.

E H Gombrich, drawing on writings of Ficino that survive from the same

period as Botticelli's painting, defines Venus in the following way: "Far

from being the Goddess of Lust . . . Venus stands for Humanitas which

. . . embraces Love and Charity, Dignity and Magnanimity, Liberality and

Magnificence, Comeliness and Modesty, Charm and Splendour."

4

A difficult concept to impart to a casual observer of the painting.

But it must be recalled that the painting was not originally meant for

general viewing; the Neoplatonists were not a movement in popular culture.

The Renaissance may have been the rebirth of the individual, but it was

not the age of the Common Man. Renaissance society was designed for the

rich, powerful and talented - an elitist society, only for those with

the benefit of a 'proper' education.

Botticelli's work presages the way that Renaissance art in Italy was

to develop: it would ultimately produce the elegant, ingenious, but basically

lifeless work of the Mannerists. The Primavera, however, dates

from the early Renaissance, and cleverly reduces one of the basic Neoplatonist

tenets into a visual equation: Nature plus Grace equals the Human Ideal.

There was a mainstream tradition in Renaissance art that

followed the lead shown by Botticelli and his contemporaries –

an example of later work that shows little difference in concept from

Botticelli's symbol paintings is Titian's Sacred and Profane Love

– but a study of the works of the three best-known Renaissance

artists, Leonardo, Michelangelo and Raphael, reveals that the Humanist

ideals could be conveyed in art in a variety of ways.

There was a mainstream tradition in Renaissance art that

followed the lead shown by Botticelli and his contemporaries –

an example of later work that shows little difference in concept from

Botticelli's symbol paintings is Titian's Sacred and Profane Love

– but a study of the works of the three best-known Renaissance

artists, Leonardo, Michelangelo and Raphael, reveals that the Humanist

ideals could be conveyed in art in a variety of ways.

Leonardo best exemplifies the idea of the 'artist as scientist' (cf.

Alberti), though Leonardo's concept was better developed than that of

his predecessor. His belief in the exact imitation of nature exceeded

Alberti's. Where the earlier artist believed that only the most beautiful

(or perfect) objects in nature should be painted, Leonardo felt that "...

provided he can make his figures real, individual, and living, it will not

matter if they do not conform to some absolute standard of harmony."

5

But in this experimentalist attitude (as in most things for which he

is known), Leonardo was not a typical artist of his time. In fact, as

the Renaissance progressed, a new formalism appeared.

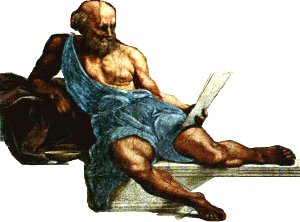

Raphael's frescoes in the Stanza della Segnatura in the Vatican

reflect this attitude, which may be called that of the 'artist as scholar'

– Neoplatonist art without the sentimentalism of the Florentine

artists. One of these frescoes is the so-called School of Athens,

representing the theme of Pagan Philosophy (other frescoes in the chamber

taking on the parts of Poetry, Theology and Justice).

The School of Athens is an encyclopedia of Classical

philosophy. The central figures are of Plato and Aristotle: Plato pointing

heavenward, expounding universal Ideals, and Aristotle indicating the

Earth, emphasizing the practical view of the world. In various groups

around them can be found Ptolemy, Socrates and Diogenes, among others.

The entire scene is presided over by statues of Apollo and Minerva. (Cleverly,

Raphael projected this representation of Classical philosophy onto his

own time by using portraits of eminent contemporaries - Leonardo and Michelangelo

among them - to depict the famous ancient philosophers.)

The School of Athens is an encyclopedia of Classical

philosophy. The central figures are of Plato and Aristotle: Plato pointing

heavenward, expounding universal Ideals, and Aristotle indicating the

Earth, emphasizing the practical view of the world. In various groups

around them can be found Ptolemy, Socrates and Diogenes, among others.

The entire scene is presided over by statues of Apollo and Minerva. (Cleverly,

Raphael projected this representation of Classical philosophy onto his

own time by using portraits of eminent contemporaries - Leonardo and Michelangelo

among them - to depict the famous ancient philosophers.)

The major significance of the Stanza as a whole is that it shows

the blending of Classical and Renaissance Christian cultures at its height.

"The disciplined ordering of all the elements in the ensemble

... is instantly and strikingly apparent. In this realm, peopled by images

in which two worlds come face to face ... it is not the clash of two armies

which we hear, but the harmony of a choir."

6

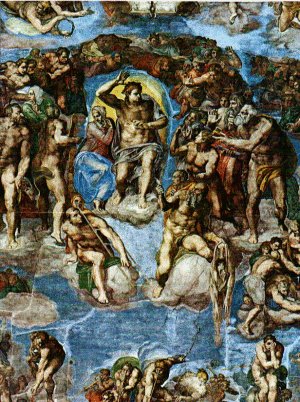

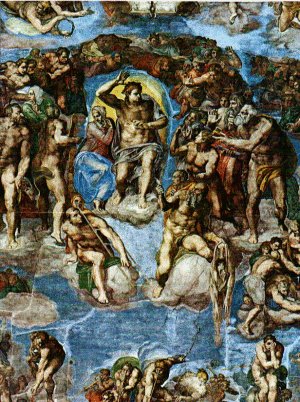

If the Stanza shows the fusion of Classical and Renaissance cultures

at its height, then Michelangelo's paintings in the Sistine chapel reflect

the discovery that this fusion was ultimately a false one.

The catalyst for this discovery was the sixteenth century's great religious

and social upheaval – the Reformation. It spelt the end of the

Italian Neoplatonist movement, and with it the end of the Italian High

Renaissance. The effect can be traced through the Sistine paintings, which

were completed over a period of more than 30 years (1508-41). When he

began his great work, Michelangelo was the archetypal Neoplatonist painter.

In fact ... "among all his contemporaries Michelangelo was the

only one who adopted Neoplatonism not in certain aspects but in its entirety,

and not as a convincing philosophical system ... but as a metaphysical

justification of his own self."

7

The early paintings (for example, The Creation of Adam)

show the extent of Michelangelo's belief in the beauty of the material

world. This belief is also revealed in Michelangelo's early poetry, where

more than once he refers to the divine origin of beauty. With the passage

of time, Michelangelo became more influenced by the sober piety of the

Counter-Reformation movement started within the Roman Church, and gave

away his ideas of physical beauty as a revelation of spiritual excellence:

the Last Judgement, also in the Sistine chapel, shows Michelangelo

no longer interested in physical beauty for its own sake. Rather, his

rugged, graceless figures are used to convey an idea of violent motion

and emotion.

The early paintings (for example, The Creation of Adam)

show the extent of Michelangelo's belief in the beauty of the material

world. This belief is also revealed in Michelangelo's early poetry, where

more than once he refers to the divine origin of beauty. With the passage

of time, Michelangelo became more influenced by the sober piety of the

Counter-Reformation movement started within the Roman Church, and gave

away his ideas of physical beauty as a revelation of spiritual excellence:

the Last Judgement, also in the Sistine chapel, shows Michelangelo

no longer interested in physical beauty for its own sake. Rather, his

rugged, graceless figures are used to convey an idea of violent motion

and emotion.

In his last years, Michelangelo renounced all his Neoplatonist ideals

in favour of an ascetic piety, and turned away completely from the figurative

arts. In one sonnet, he wrote:

"Thus I now know how fraught with

error was the fond imagination which made Art my idol and my king, and

how mistaken that earthly love which all men seek in their own despite

... no brush, no chisel will quieten the soul."

This poem can apply equally to the entire Humanist movement of the time:

some of its adherents broke from the Church of Rome, and strove to abolish

the 'idolatry' of Rome; others tried to reform the Roman Church by rejecting

pagan influences and returning to an austere form of Christianity. In

both cases, it was the art of the time that suffered.

In short, it was the infusion of the Classical influence that heralded

the Renaissance in art, and it was the turning away from the Classical

heritage that marked the closing of the Renaissance in Italy.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

RETURN TO CONTENTS PAGE

The origin of the Venus and Mars is directly from

Classical myth. The scene depicted is of the divine couple just prior

to their discovery by Vulcan, Venus' husband, but the concept illustrated

has little to do with marital triangles, but is instead a visual corollary

to a commentary on one of Plato's works by Marsilio Ficino, leader of

the Neoplatonist revival in Florence.

The origin of the Venus and Mars is directly from

Classical myth. The scene depicted is of the divine couple just prior

to their discovery by Vulcan, Venus' husband, but the concept illustrated

has little to do with marital triangles, but is instead a visual corollary

to a commentary on one of Plato's works by Marsilio Ficino, leader of

the Neoplatonist revival in Florence.

The second of Botticelli's works discussed here also

has love as a central theme, though the symbolism is less readily apparent.

The Primavera seems cluttered: there are eight major figures (excluding

the Cupid, which is included primarily as part of the standard Venus/Cupid

couplet, and all can be identified with characters out of Classical mythology.

The second of Botticelli's works discussed here also

has love as a central theme, though the symbolism is less readily apparent.

The Primavera seems cluttered: there are eight major figures (excluding

the Cupid, which is included primarily as part of the standard Venus/Cupid

couplet, and all can be identified with characters out of Classical mythology.

There was a mainstream tradition in Renaissance art that

followed the lead shown by Botticelli and his contemporaries –

an example of later work that shows little difference in concept from

Botticelli's symbol paintings is Titian's Sacred and Profane Love

– but a study of the works of the three best-known Renaissance

artists, Leonardo, Michelangelo and Raphael, reveals that the Humanist

ideals could be conveyed in art in a variety of ways.

There was a mainstream tradition in Renaissance art that

followed the lead shown by Botticelli and his contemporaries –

an example of later work that shows little difference in concept from

Botticelli's symbol paintings is Titian's Sacred and Profane Love

– but a study of the works of the three best-known Renaissance

artists, Leonardo, Michelangelo and Raphael, reveals that the Humanist

ideals could be conveyed in art in a variety of ways.  The School of Athens is an encyclopedia of Classical

philosophy. The central figures are of Plato and Aristotle: Plato pointing

heavenward, expounding universal Ideals, and Aristotle indicating the

Earth, emphasizing the practical view of the world. In various groups

around them can be found Ptolemy, Socrates and Diogenes, among others.

The entire scene is presided over by statues of Apollo and Minerva. (Cleverly,

Raphael projected this representation of Classical philosophy onto his

own time by using portraits of eminent contemporaries - Leonardo and Michelangelo

among them - to depict the famous ancient philosophers.)

The School of Athens is an encyclopedia of Classical

philosophy. The central figures are of Plato and Aristotle: Plato pointing

heavenward, expounding universal Ideals, and Aristotle indicating the

Earth, emphasizing the practical view of the world. In various groups

around them can be found Ptolemy, Socrates and Diogenes, among others.

The entire scene is presided over by statues of Apollo and Minerva. (Cleverly,

Raphael projected this representation of Classical philosophy onto his

own time by using portraits of eminent contemporaries - Leonardo and Michelangelo

among them - to depict the famous ancient philosophers.)  The early paintings (for example, The Creation of Adam)

show the extent of Michelangelo's belief in the beauty of the material

world. This belief is also revealed in Michelangelo's early poetry, where

more than once he refers to the divine origin of beauty. With the passage

of time, Michelangelo became more influenced by the sober piety of the

Counter-Reformation movement started within the Roman Church, and gave

away his ideas of physical beauty as a revelation of spiritual excellence:

the Last Judgement, also in the Sistine chapel, shows Michelangelo

no longer interested in physical beauty for its own sake. Rather, his

rugged, graceless figures are used to convey an idea of violent motion

and emotion.

The early paintings (for example, The Creation of Adam)

show the extent of Michelangelo's belief in the beauty of the material

world. This belief is also revealed in Michelangelo's early poetry, where

more than once he refers to the divine origin of beauty. With the passage

of time, Michelangelo became more influenced by the sober piety of the

Counter-Reformation movement started within the Roman Church, and gave

away his ideas of physical beauty as a revelation of spiritual excellence:

the Last Judgement, also in the Sistine chapel, shows Michelangelo

no longer interested in physical beauty for its own sake. Rather, his

rugged, graceless figures are used to convey an idea of violent motion

and emotion.