| The Thomas Flyer | 1908 Olympic Games | The first fatal aircrash |

|

|

|

|---|

- February - 18 Japanese immigration to the U.S.A. is forbidden.

- March - 1 Seven social revolutionaries allegedly involved in an attack on Stolypin, (1862-1911), the Prime Minister of Russia, are executed. From 1906 -1909, over 3,000 suspects were speedily convicted and executed by special courts set up by him to deal with revolutionary unrest.

- March - 27 The German Reichstag adopted an amendment at third reading of the naval bill, which allows for four instead of two battleships of the 'Dreadnought' class annually, until 1911, to be built. This exacerbates, again, the arms race between the German Reich and Great Britain.

- March 9 - The Internazionale Football Club is founded in Milan, Italy.

- April 3 - British Prime Minister Henry Campbell-Bannerman, (1836-1908), steps back because of health reasons. He was to die in Downing Street on 22nd of April, uttering his final words, "This is not the end of me". The former Chancellor, Herbert H. Asquith, becomes the new Head of Government.

- April 27 - The opening ceremony of the London Olympics is held and will involve 2,035 athletes from 22 participating countries in 22 sports.

- May - 26 The first major commercial oil discovery in the Middle East is made at Masjed Soleiman ( مسجد سلیمان ), in present day Iran. The rights are immediately acquired by the British through the Anglo-Bakhtiari Oil Company.

- June - 9 King Edward VII visits Tsar Nicholas II at Reval (now Tallinn), and 'unconstitutionally' bestows the rank of honorary admiral of the fleet on Nicholas II. The strengthening of ties between the two increases anxiety in Berlin about being encircled.

- June - 21 Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, (1844-1908), the Russian composer, dies in Ljubensk at Luga

- June - 21 London experiences the largest demonstration for women's suffrage. At the "Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU), organized in Hyde Park, 250,000 people take part.

- July - 21 Bernhard Dernburg, colonial minister, inaugurates a new railway line in German South West Africa. It commences at the port city, Lüderitzbucht, a town near Angra Pequena, which is Portuguese for "small cove", where the Portuguese explorer Bartolomeu Dias anchored in 1487, but it was made into a trading station by the German, Adolf Lüderitz, in 1883, having concluded treaties with neighbouring chiefs, although islands off the coast of Angra Pequena, rich in guano deposits, were annexed by Great Britain in 1867 and added to Cape Colony in 1874.The railway line ends at Keetmanshoop On.

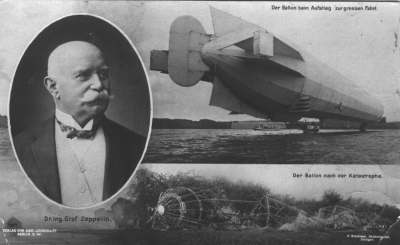

| Sultan Abd Al Hamid II | The 'LZ 4' airship disaster. | Messina earthquake |

|

|

|

|---|

- July - 24The Ottoman Sultan, Abd Al Hamid II (عبد الحميد ثانی ), (1842-1918), under pressure from the army and the Young Turks brings back into force the liberal constitution from 1876. At the same time, the autocrat announces the release of all political prisoners, the lifting of censorship, and the abolition of the secret police.

- July - 31As part of the festivities for 350 year existence of the University of Jena (now renamed the Friedrich Schiller University), a new university building and the Phyletic museum founded by Ernst Haeckel are inaugurated.

- August - 5 The airship "LZ 4" makes an intermediate landing, after a 24-hour trip, in Echterdingen near Stuttgart but is destroyed by a sudden storm. The "LZ 4", developed and built by Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin, was 135 m in long and 13 m in diameter, the largest German airship built so far. It temporarily exhausts his financial resources.

- August - 25 The death of French physicist Antoine Henri Becquerel in Le Croisic.

- September - 1 In Dresden, there opened a new exhibition of the "Die Brücke" group of artists .

- September - 17 During a flight demonstration at Ft. Myer, Virginia, Thomas Selfridge, First Lieutenant in the U.S. Army, becomes is the first person to die from an airplane crash. The pilot, Orville Wright, is severely injured with several fractures in the same crash, but recovers.

- October - 5/6 Austria-Hungary declares the annexation of the Balkan countries of Bosnia and Herzegovina, occupied since 1878, formerly belonging to the Ottoman Empire, and thus aggravate the conflict with the Kingdom of Serbia, which is based on the support of Russia. On the same day Prince Ferdinand, (1861-1948), proclaims Bulgaria's independence and calls himself the Tsar. In the wake of the declaration of independence by Bulgaria, the island of Crete also dissolves its ties to the Ottoman Empire and announces its connection to Greece.

- October - 28 The interview of Kaiser Wilhelm II,(1859-1941) with the British newspaper, the 'Daily Telegraph', arouses fierce criticism in Germany and abroad, above all for his condescending and overbearing comments on the English character, and the conduct of Germany towards Britain in the Boer War.

- November - 1 Russia does not recognise the annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina by Austria-Hungary.

- November - 14 The Chinese Emperor Guangxu, (1871-1908), dies in Beijing, a day before Empress Dowager Cixi (1835-1908). She names a two-year nephew, Pu Yi, (1906-1967), as his successor. He is the last emperor of China.

- December - 28 A devastating earthquake on the island of Sicily, destroys the cities of Messina and Reggio di Calabria and over 100,000 people die.

Back to TOP

Other events of 1908

Another early |

Illustrations : Becquerel plate E. Rutherford I. Mechnikov Bipinnaria, larval form of starfish Daphnia, P. Ehrlich R. Eucken Lippmann G. Lippmann |

At the end of the previous century, German artists, like those in France, had openly begun to rebel against, and to criticise the stance adopted by the established academic institutions of art. In France, this movement was early, and flashed brilliantly in the work of impressionists and the artists who succeeded them. Many of their ideas which found ready acceptance amongst younger artists were transmitted to many other countries in Europe. In Germany, conservativism kept a firm hold for much longer, and artists tried to find new means of representation mainly in landscape, which had always had strong roots in the historical development of German art, and in the neo-romantic currents present at the time. The immediate influence on German artists, as also on many English artists in the latter half of the nineteenth century, was of the Barbizon school, founded, amongst others, by Théodore Rousseau, although the artists of that school had always considered the landscapes of Constable to be the most important influence in their own portrayal of landscape. In Germany, even this trend, by no means as radical as what followed in the space of a few years, was frowned upon by the salons, and rejected by authority.

|

|

|

The effect of such repression was certainly felt by

individuals like Hugo von Tschudi, (1851-1911),

who was appointed Director of the National Gallery in Berlin

in 1896. He brought back many contemorary paintings

from France, and tried to hang them in a favourable

position, while giving less privileged exposure to the

academicians at the gallery. The Kaiser, Wilhelm II, and the

man who taught him painting, Anton von Werner, were not

at all pleased by seeing these academic paintings relegated

to the storerooms, and forced Tschudi to retract. Tschudi

restored some of his favour by purchasing works of the

Barbizon artists. All the same, in 1898, the rejection from

the Great Art Exhibition of the painting,

'Grunewaldsee', by Walter Leistikow,

(1865-1908), depicting a forest landscape near Berlin,

because the scene had irritated the Kaiser, Wilhelm II,* had

led to the formation of the Berlin Secession, a group of

disaffected artists who had been holding their own annual

shows. A similar group was also formed in Munich.

[*'Seine Majestät belehrte ihn sehr ungnädig,

daß in diesem Bilde nicht die geringste Naturwahrheit

wäre: "Er kenne den Grunewald und außerdem

wäre Er Jägerr".' - from Corinth, Lovis; 'Das

Leben Walter Leistikows', Berlin, Bruno Cassirer, 1910]

|

|

|

The authorities ranged against the newer trends were to prevail, however, and with continuous intrigues, Tschudi was forced away on annual leave in 1908, never to return to the Berlin Gallery. At the same time younger artists, such as those who had formed 'Die Brücke' (The Bridge), inspired by the work of artists like Emil Nolde, and the techniques used by the French Fauvistes, had already crossed over into entirely new territory, and were painting debauched outcasts with a raw, biting edge, full of melancholy, and landscapes executed in brilliant streaks of pure vibrant colours. If this last, and other movements, developed as a reaction against the late romantic paintings of the previous century, the increasing use of photography must also have played a prominent part in this negation of painterly realism, for the photographic image was all too easily reproducible, by now, from the photographic plate, and offered vistas not previously imagined in the fine arts. Examples of both are reproduced below.

|

Two memebers of 'Die Brücke'

|

|

|

Poetry:'The cherry trees'

The cherry trees bend over and are shedding

On the old road where all that passed are dead,

Their petals, strewing the grass as for a wedding

This early May morn when there is none to wed.

Poem by Edward Thomas (1878 - 1917).

For text of original historical documents related to this site

visit  HATI ZA KALE NA ZA LEO

HATI ZA KALE NA ZA LEO

| © M. E. Kudrati, 2009: This document may be reproduced and redistributed, but only in its entirety and with full acknowledgement of its source and authorship. All rights reserved |

|---|