with Aileen Mioko Sprauge Smith

... as told by John Godfrey Morris in his book "Get The Picture: A Personal History of Photojournalism

(or return to page 1)

A Personal History of Photojournalism John Godfrey Morris © 1968 Random House, Inc., New York, U.S. Get the Picture is an extraordinary account of one of the most interesting lives of the twentieth century. John Morris has been present and engaged, as few others have been, with the definitive and decisive moments of modern history. Possibly no living person has had such an extensive involvement with the world of photographic expression, with the great photographers and photographs of this century. From Cartier-Bresson to Robert Capa to William Eugene Smith to most of the living greats, Morris was with them, giving spiritual guidance and unfaltering fraternity, and embraced with passion the pursuit of justice and excellence. His words and life represent one of the great stories of our time [written in 1998]. - David and Peter Turnley, photojournalists, co-authors of Beijing Spring and Moments of Revolution "Not only is John Morris's Get the Picture an extraordinary history of photojournalism - it is as well an exciting, revealing trip through the intricacies of picture publishing in its truest light. A real pageturner that had me still reading at sunup. Don't miss it." - Gordon Parks, photojournalist, author of Half Post Autumn [written in 1998] FPT U.S.A. $30.00 Canada $42.00 In his long and distinguished career as a journalist and picture editor, John Godfrey Morris had one simple - and stunningly complex - assignment: Get the picture. "Picture editors," Morris writes, "are the unwitting (or witting, as the case may be) tastemakers, the unappointed guardians of morality, the talent brokers, the accomplices to celebrity. Most important - or disturbing - they are the fixers of 'reality' and of 'history'. Indeed, Morris commissioned, edited, and published the photos that have helped define our sense of recent history, and he worked closely with some of the century's great photographers, including Robert Capa, Henri Cartier-Bresson, and William Eugene Smith. Get the Picture is Morris's fascinating account of a half century of photojournalism, from Capa's heroism on D-Day to the special ethical problems that arose for photographers and their editors on the night Princess Diana died in a Paris tunnel while trying to avoid the paparazzi.

Get the Picture is also a book about lasting friendships and the importance of professional and personal commitment under impossible circumstances. Morris writes movingly about the tragic deaths of his colleagues Robert Capa, Verner Bischof, David "Chim" Seymour, and William Eugene Smith, and about what was required to carry on without them. Above all, Get the Picture is about a life vigorously lived, and Morris is still going strong [as of 1998] as one of the leading proponents of a journalism committed to the unflinching, unblinking truth. 115 BLACK-AND-WHITE PHOTOGRAPHS John Godfrey Morris grew up in Chicago and was educated at the University of Chicago. He was a Hollywood correspondent for Life, picture editor for Life's London bureau during the war years, picture editor at Ladies' Home Journal, the first executive editor of Magnum Photos, picture editor for both The Washington Post and The New York Times, and a correspondent and editor for National Geographic. Morris lives in Paris with his wife, photographer Tana Hoban [as of 1998]. Jacket design: John A. LaMacchia Random House, Inc., New York, N.Y. 10022 http://www.randomhouse.com [apparently out of print - used or library copies available only] Printed in U.S.A. 6/98 © 1998 Random House, Inc. |

|

The

following has been edited for content about William Eugene Smith

from the book:

Get The Picture A Personal History of Photojournalism by John Godfrey Morris © 1968 Random House, Inc., New York, US

[Page 97] ... When V-E Day finally came, on May 8, I did not feel much like celebrating. Thousands of Americans were still fighting and dying in the Pacific theater. Gene Smith was severely wounded on Okinawa on May 21 [1945]. I was inducted into the U.S. Air Force on June 15 and ordered to the Texas panhandle for, of all absurd things, basic training. FDR [United States President Franklin Delano Roosevelt] had recently died, and now we had a new president Harry S. Truman. I had once found myself with him in an elevator, where we were introduced by Life photographer Tom McAvoy. A nice fellow, I remember thinking of Truman at the time. On August 6, Truman gave the order to drop the atomic bomb on Hiroshima, and the Pacific war was soon over ... [Page 129] ... World War II had left me unscathed, but, like many other innocent Americans, I almost became a casualty of the Cold War. My crime: defending the Photo League, a New York organization of socially conscious photographers that had been founded in the early thirties. The Photo League held discussions and exhibitions, ran a school for aspiring photographers, and conducted group photographic projects, such as "Harlem Document". Some of America's most distinguished photographers supported the League: Paul Strand, Lewis Hine, Margaret Bourke-White, William Eugene Smith, Ansel Adams, Aaron Siskind. I had spoken twice in their symposiums and had contributed to their bulletin, Photo Notes ... [Page 148] ... It was not the kind of day to talk business, yet it was too early for serious eating or drinking. Looking at his watch, Capa declared that we could easily make the first race at Longchamp. We checked me into the hotel and took off. Despite my working visits to Saratoga with Alfred Eisenstaedt and William Eugene Smith for Life [magazine], I had never placed a bet on a horse. Capa agreed to be my instructor. For the first race, the Prix Blangy with a purse of 300,000 francs, we placed my bet on a filly called Hasty Heart. The odds were three to one, and I won. For the second race, I bet on a horse owned by Baron Guy de Rothschild. Again I won. Meanwhile, Capa was losing. In the third race my horse came in fourth. Capa then introduced me to the intricacies of the jumelé meaning twin bet, where you win if you pick the first two horses in order. I won. By now I had an armful of francs and Capa had lost just as heavily. It was a bit too much for him, so I tactfully lost for the rest of the afternoon ...

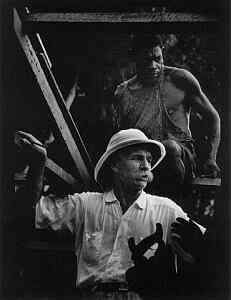

[Page 181, the entire Chapter 20] The Many Woes of William Eugene Smith I thought I knew Gene Smith. Hadn't we worked happily together on the eve of World War II? We had gone off to war in opposite directions, but I shared his passionate belief in the idiocy of war and his frustration at the way it had been presented in the press. When Gene's first postwar Life essays appeared, they hit me as a revelation of photojournalism in depth. Each reflected the standards I wanted to set for the journal's "How America Lives". In "Country Doctor" (1948), Gene lived with his subject for weeks, "fading into the wallpaper" to record the daily trauma embodied in the practice of Dr. Ernest Ceriani of Kremmling, Colorado [sample images below]. In "Nurse Midwife" (1951), Gene found a heroine in Maude Callen, a South Carolina midwife. It was the first time a black person had been featured by Life in such a way. Readers sent thousands of dollars to build Maude a new clinic. "Spanish Village" (1951), designed by Life's Bernard Quint, was hailed as the greatest of all Life's photo-essays [sample images below]. Gene resigned his Life contract on November 2, 1954, as the magazine closed his twelve-page photo-essay on Albert Schweitzer, "A Man of Mercy" [sample image below]. The massive project had consumed Gene for almost a year, and he felt that the published layout did not do his effort justice: "I would have preferred silence," he said. Harry Luce wrote to Gene to express his regret, adding that he hoped Gene's pictures "will still be available, although from the other side of the counter". The moment I heard the news, I thought of Gene for Magnum. I was excited at the prospect. I talked up the idea with Cornell Capa and Ernst Haas, but I had no idea how disturbed Gene had become. I did not know that he had been admitted to Bellevue Hospital for psychiatric treatment following his return from "The Spanish Village" in 1950, which delayed its publication to 1951. Gene then quit the Life staff for a contract that required him to produce only three stories a year; he actually produced only one of importance in 1952, "Chaplin at Work," and one in 1953, "The Reign of Chemistry". I did not realize that he had been, consciously or unconsciously, seeking an excuse to quit Life entirely. Schweitzer was but the pretext. I knew he was having an affair with photographer - writer Margery Lewis, but I did not know that she had secretly given birth to his son, Kevin Eugene Smith, while he was off with Schweitzer in 1954. Meanwhile, he had failed to support his own family - his wife, Carmen, and four children. He was combining heavy drinking with amphetamines. Life was the only magazine in the world capable of supporting Gene's leisurely rate of performance and his expensive habits - he invariably worked with an assistant and the very best of equipment. It was, I realized too late, foolhardy of Magnum to commit itself to sustaining Gene Smith and his burdens, both real and imaginary. To compound our problem, the first deal I made for Gene was the worst I have ever made for any photographer. Gene's first customer actually appeared on the scene even before Gene joined us. I knew Stefan Lorant's reputation as the innovative but tricky Hungarian who had edited no fewer than four photographic magazines. The anti-Nazi views of his Münchner Illustrierte Zeitung had won him six months in a German concentration camp in 1933; only the intervention of the Hungarian government had gotten him out. Taking refuge in England, he had founded Weekly Illustrated in 1934, Lilliput in 1937, and Picture Post in 1938. Winston Churchill then suggested that he do a book explaining America to Englishmen. Introduced to Harry Luce by Joseph P. Kennedy, then the American Ambassador to the Court of St. James's, he visited Time, Inc. and returned to England with hundreds of pictures. The next year he emigrated to the United States for good. Settling in Lenox, Massachusetts, Lorant turned to editing photographic books rather than magazines. When we met, Lorant had just been commissioned by the Allegheny Conference to do an illustrated book to celebrate Pittsburgh's bicentennial. He wanted Gene Smith to shoot a picture essay on contemporary Pittsburgh as the book's centerpiece. "Unfortunately," Lorant explained to me, his budget did not "permit" him to pay more than $1,200, plus $500 for expenses, but all he needed was book rights; the second rights - which would stay with the photographer - would be "invaluable". As for expenses, Gene could live on the bottom floor of a house a Pittsburgh executive had loaned to Lorant. It even had a darkroom. Gene was almost eager to accept - he was going to show Life. I should have known better, but I agreed to the deal-verbally. Gene went off to Pittsburgh with enough equipment, and phonograph records, to stay a year. Lorant had figured on two to three weeks.

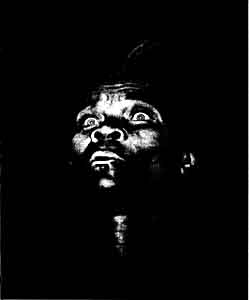

The next problem was where to sell Gene's mammoth photo-essay. We couldn't very well go to Life; Gene wanted to "show them" he could survive without Time, Inc. During his stay in Pittsburgh, we had been forced to turn down an assignment offered Gene by The Saturday Evening Post on radio announcer Arthur Godfrey. Later we had to turn down Colleir's - a "peace" essay for Christmas. Neither had the slightest interest in Pittsburgh. Of the "big four" large-format mass magazines, that left only Look. By this time, Smith and Karales had filled both the dining room and living room of the big house in Croton with proof prints - thousands of them, tacked up on easels. They were so impressive en masse that I decided to invite prospective customers to Croton. Look's art director, Allen Hurlburt, and man aging editor, William Arthur, came first; they reported back favorably to editor Dan Mich. We even agreed on a price, $20,000. It all became moot, however, when Mich asked Lorant to write the text. Lorant was furious, insisting that he had bought first rights, period, and had no intention of yielding them for any magazine piece. Mich, understandably, withdrew Look's offer. By now Smith had tied up virtually all of Magnum's capital; there was no way out until we somehow sold Pittsburgh. I consulted Howard Squadron, Magnum's lawyer, who filed suit against Lorant. Lorant filed a countersuit. Gene also took the unprecedented step of registering his personal copyright with the Library of Congress on three huge volumes of contact prints - 11,000 images - under the title "A City Experienced: Pittsburgh, Pa". At this, Lorant agreed to negotiate. In a five-hour meeting, attorneys for both sides came to an understanding that Gene could sell one magazine essay and three ads prior to book publication. My signature on the contract had cost us almost a year. Now we could only go crawling back to Life, whose editors, bless them, didn't rub it in. I went to Robert Elson, the deputy managing editor whose "arbitrary" closure of the Schweitzer story had caused Gene to resign. After checking with Ed Thompson, Elson authorized a $2,500 down payment. That was in July. In October, Life was still waiting to see the pictures. It was obvious that Gene's concept of the story was very vague. He described it as "an experience that is Pittsburgh". Smith wanted to bring in his own layouts. Thompson refused to look at anything but the photographs and assigned deputy art director Bernard Quint, who had done the famous "Spanish Village" essay, to make a layout. Smith worked with Quint, but when Thompson asked Gene if he approved the layout, he only mumbled something that sounded critical and walked out. Thompson interpreted this as rejection. I only wish I had been there. No further payment was made. Finally, in 1958, after an international Popular Photography poll voted Smith one of "the world's ten greatest photographers", Bruce Downes, who edited both "Pop" and a sister publication, Photography Annual, agreed to run Smith's layout of thirty-two pages - later increased to thirty-eight - in the Annual exactly as Gene wanted. The fee was fifty dollars a page, including text - the usual rate for a magazine aimed at amateurs. Gene insisted that the essay be called "Labyrinthian Walk". Indeed it was. Gene was utterly depressed when he saw the final result, far from Life's size and quality. "Pittsburgh is dead," he wrote to one friend, and to Ansel Adams: "The presentation is the witness ... and there it lies, a failure." The textbook in selfdestructiveness was written, in the red ink of his own blood, by William Eugene Smith himself. Pittsburgh was so all-consuming that Gene could do little else in his first three Magnum years. Ladies' Home Journal sent him to photograph a black professor in the South, an assignment that constituted most of his $2,582.78 magazine income for the year 1955. In 1956, when the Italian liner Andrea Doria sank off Nantucket after colliding with the Swedish liner Stockholm, I got Gene to work with me through the night to cover the arrival of survivors at Pier 88 in New York. Gene made a number of good pictures and one classic - a young nun, a woman of spectral beauty, holds her fingers gently to her lips in an expression of utter anxiety; in her other hand she grips a teddy bear, intended for one of the surviving children of the disaster. To my dismay, Life rejected the picture. Gene's greatest success during his years with Magnum was one neither he nor Magnum had much to do with - credit goes to Edward Steichen for selecting Gene's backyard photograph, which he called "The Walk to Paradise Garden", of Gene's children Patrick and Juanita as the final image of "The Family of Man". Taken in 1946, it had been rejected by Life, where Wayne Miller found it buried in a file. It has since become what art historians call an "icon" of the twentieth century. Perhaps because the faces of the children are unseen, people see them as their own, toddling into the future. Magnum records show that we sold twelve prints of it, made by Gene himself from the copy negative, for fifty dollars each, in 1955. Today [1998] such prints sell for thousands of dollars. Gene's real needs were immense. His advances from Magnum amounted to a dole that finally added up to $7,000, more than Magnum's original capital. We couldn't do more as a company, but we did join Gene in begging from friends. The Smiths' housekeeper, Jasmine "Jas" Twyman, who lived with her daughter in the Croton [New York] house, went out to do day work in other people's houses to earn money for food - for the Smiths as well as herself. One Christmas, Louise Lewis, the black matriarch who was nobly helping us out in Armonk [New York], cooked two big dinners. One I took over the hills to Croton. Gene was not there - he could no longer face his family problems and had moved into a loft on Sixth Avenue, in the wholesale flower district [in New York City]. In stark awareness of his desperate situation, Gene wrote to me on January 25, 1958, "I have been a misfortune to Magnum from the day of being part of Magnum, and I am now in a far worse position than I was at the beginning to be anything but a handicap to Magnum. My failure with Magnum has been so devastatingly monumental, twisting so dangerously about both our necks, that I believe there is no other course than resignation." I persuaded Gene to stay on until the end of that year, hoping to recoup the money he owed Magnum. That spring, sitting next to me on the commuter train, a young Armonk neighbor and philanthropist named John Heyman told me that he was soon bound for Haiti with Dr. Nathan Kline, a prominent New York psychiatrist. Kline had persuaded some drug companies to fund a modern mental health clinic in Port-au-Prince to replace a "snake pit" that was one of the world's most primitive mental institutions. I jumped. I knew exactly the place he was talking about. In January 1953, after leaving the journal and before starting at Magnum, Dèle and I had vacationed in Haiti. We had made friends there with De Witt Peters, the American who had founded the Centre d'Art, for the promotion of Haitian primitive art. Through him we met several of Haiti's leading painters and also a man, straight out of Graham Greene's The Comedians, named "Doc" Reser. He had come to Haiti as a U.S. Marine during the long-lasting U.S. occupation (1915-1934) and had stayed on. One Sunday afternoon, Peters drove us out of Port-au-Prince and down a dusty country road to the modest frame house where Reser lived with a Haitian woman. Reser invited us to "see something" nearby. We drove a mile or so, then turned into a wooded area where there were barracks, scattered like cow barns, with adjacent corrals. Soon we saw that the animals they enclosed, living on the bare dirt and excrement, were silent men and women, dressed in rags. "This is Haiti's home for the insane," said Reser. He had visited it for years, doing what he could to soothe the suffering of the inmates and to stir public sympathy. I described my visit there to John Heyman and then told him about Gene Smith. In no time he agreed to hire Gene to document Kline's project. Gene went twice to Haiti, once for the "Before" (the "snake pit"), once for the 'After" (the new clinic) - although of course it was not as simple as that. He produced some stark images, including one he called simply "Mad Eyes" [illustrated above]. I went along with Gene for the second tour, staying with him at the Olafson, the rather seedy but charming hotel made memorable by Graham Greene in The Comedians. It had come into the hands of Roger Coster, a French photographer who had been a Magnum stringer; he refused to charge us rent. We covered the dedication of the new clinic, followed by a reception at the Maison Blanche given by President "Papa Doc" Duvalier. Was it an odd sensation to drink champagne with Haiti's dictator? Was it the most improbable cocktail party I have ever attended? Yes to both. [Page 197] ... My biggest challenge was to find support for a group news project. In 1957, five Magnum photographers, in response to European demand, jointly covered the visit of Queen Elizabeth and her consort, Philip, to the United States. We processed, edited, and shipped the story on a daily basis during the entire week. I hired Lee Jones, the tall and stately picture editor who had just quit her job at This Week, to assist. On the queen's final day in New York, Cornell Capa sailed with her past the Statue of Liberty; Ernst Haas, mounted on a weapons carrier, rode with her parade up Broadway. Burt Glinn shot down from 1 Wall Street, and Gene Smith worked the street, capturing the Sanitation Department's sweepers in formation. Dennis Stock awaited her at City Hall. The photographers then leapfrogged to get her at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, the United Nations, the Empire State Building, Rockefeller Center (with Haas secreted in a beauty salon), back to a Waldorf banquet, then to Idlewild Airport. Great fun ...

After Gene The morning of October 16, 1978, I had an appointment at the Arizona Mortuary on University Boulevard in Tucson. It was there that I looked into the face of William Eugene Smith for the last time. It was curiously relaxed, as if to say, "Now it's up to you." Which it was. Two years before, Gene had asked me to be the executor of his estate. Now, after consulting his children, I had to release his neatly dressed corpse to the flames of the crematory I thought of all the times that Gene had threatened suicide, in order to get his way. His father's suicide had made credible this dreadful weapon of the depressed. Gene seemed often to have sufficient cause. Lincoln Kirstein, Gene's friend and admirer, once said, "A full account of Smith's life would be too painful to write.'' Kirstein spoke too soon. In his last decade, William Eugene Smith transcended his troubles. He found his manifest destiny despite his despair, embracing defeat in a special kind of triumph. During his Magnum years Gene had rented a loft on Sixth Avenue, in Manhattan's wholesale flower district. I seldom visited Gene there. I simply found it too painful. I could not help but think of the family he had abandoned in Croton. Gene's sense of black humor may have kept him going, but it only depressed me. Three remarkable young women sustained him during that time, when he was virtually an outcast from the profession of photojournalism. United in their fascination with Gene and sympathy for one another, there never seemed to be any jealousy among them. First there was Carole Thomas, a seventeen-year-old art student when she came to him in 1959. They fell in love and talked of marriage, but Gene was not divorced. In 1960, they had a sudden, totally unexpected opportunity to escape this dilemma. Gene was invited by Hitachi, makers of everything from turbines to transistors, to spend nine months in Japan on a huge industrial assignment in twenty-seven locations. In a repeat of the Pittsburgh performance, Gene took an overabundance of pictures. Upon their return, he became increasingly dependent on Carole while continuing to drink and take drugs. When he became impossible, Carole would leave him, returning when he appeared to straighten out. Gene finally obtained a divorce from Carmen, but as an actual wedding approached Carole came to her senses. She fled to California, where she has lived ever since. Gene was devastated. For months his behavior was erratic. He repeatedly threatened suicide. Midge and I received more than one such call; Gene's son Patrick and his wife, Phyllis, would often drive into the city in the middle of the night in response to his pleas. In the summer of 1969, Gene met Leslie Teicholz at Woodstock. She was shooting publicity pictures for Channel 13, New York City's public television station. Gene offered her work at his loft. She knew that he was looking for a replacement for Carole and so declined. But he persisted, and she was finally persuaded to join him in his work - nothing personal. Leslie happened to be at the loft the afternoon Cornell Capa called Gene to offer him a retrospective show at the Jewish Museum under the auspices of the Fund for Concerned Photography. Spontaneously, Gene told Cornell that he would do it, but only if "this person Leslie" would help. Originally planned for New York's Museum of Modern Art as a show of two to three hundred prints, the Smith exhibition grew and grew at the Jewish Museum, winding up with approximately 542 images, including a tray of continuously projected slides on World War II. Gene called it "Let Truth Be the Prejudice". Leslie's role was crucial. With tactful persistence, she kept Gene on track for the year that the show took to prepare but kept resisting his romantic overtures. Gene lived on love. Occasionally he would go to Philadelphia to see Margery Lewis, who by now had changed her name to Smith, and their son, Kevin. On August 2, 1970, returning from such a visit, Gene was surrounded by a gang of black youths a few blocks from the station in Philadelphia. They stripped him of his cameras and clothes and threw baseballs at his naked testicles. A few days later, Gene told Peter Pollock of the Art Institute of Chicago, who had come to visit, "I realized what they were doing. I was to be 'the nigger' at whom whites have always thrown baseballs at country fairs and circuses." A few weeks later, a TV crew came from Japan to do a Fuji film commercial. A twenty year-old Japanese-American girl from Stanford University came along as interpreter. Aileen Mioko Sprague knew little about photography and had never heard of William Eugene Smith. When they left, Aileen stayed behind. She never returned to Stanford; instead, she became Gene's personal assistant for the "Jewish Museum Show," the name that sticks with it to this day. She soon moved into the loft. He proposed marriage on numerous occasions.

For eighteen dollars a month the Smiths rented a house belonging to one of the victimized families, sharing a dirt-floored kitchen and bath, where they developed film. One by one they got to know the sufferers: Shinobu Sakamoto, a lovely teenager who often thought of killing herself, Tomiji Matsuda, a young baseball fan who would never have a chance to play the game-he was blind; Takako Isayama, a child who had to be carried everywhere but had the strength to say "Strawberries - wow!"; and Tomoko Uemura, who was blind and speechless and whose limbs were deformed. Gene Smith's photograph of Tomoko being bathed in her mother's arms became the symbol of Minamata and has been described as the pietà of our industrial age. On January 7, 1972, the Smiths joined a delegation of patients from Minamata for a demonstration at Chisso's Got plant, near Tokyo. With clear deceit, Chisso permitted them to enter. Once inside, Gene and several others were seized and beaten. Gene was first kicked, then picked up by six men who "slammed my head against the concrete, the way you would kill a rattlesnake if you had him by the tail." Then he was tossed outside the gate. He would suffer enduring pain from that beating for the rest of his life. The incident made Gene's a familiar face on Japanese TV. A courageous Tokyo department store opened a two-hundred-print show on Minamata. Almost fifty thousand people went through it in twelve days. The Smiths' next objective was a book on Minamata. They had hardly begun work on it when Gene, traveling by train from Tokyo to Minamata, began vomiting blood and had to be rushed to the Shizuoka city hospital. Aileen took an all-night train and arrived the next morning. Two months later there was another emergency. Gene called Jim Hughes, editor of Camera 35 (and Gene's future biographer), in New York. He had had a relapse, was abusing drugs and drink again, and Aileen was not around. Gene needed medical attention, and he was far from home. Hughes, who had just published twenty-four pages of the Smiths' Minamata pictures (Aileen had wielded the camera as well), called around until he found an angel in the person of Larry Schiller, the Los Angeles-based photographer/editor/movie producer and ingenious fast-talker who had sold me Jack Ruby's story in 1964. Larry admired Smith and agreed not only to put up airfare for Gene's return but to send photographer Paul Fusco from California to help bring him back. After he had had a chance to recuperate in the States, Gene and Aileen returned to Minamata for the summer and fall of 1974. They wanted the people of Minamata to see their own story in photographs. Gene was if, but they worked on the book. Gene wrote to me, "If we can finish it, the Minamata book will be its own landmark." Their next year was one of public acclaim and private misery. The book was published, and the International Center of Photography exhibited their photos of Minamata. Thanks to them, this small city became a world symbol of environmental hazards and, as The New York Times called it, "a case study in Japanese politics." Midge and I had talked Gene and Aileen into making a joint appearance at the 1975 NPPA convention at Jackson Hole,and it was there that we learned what was going on in their lives. Their marriage was failing apart, but they played the charade of togetherness. Aileen had reached the breaking point in Japan. She realized that she would have to assert her independence if she was to survive. To cushion himself, Gene had established a standby relationship with Sherry Suris, a young New York freelance photographer. Back in New York, Aileen found a place of her own. In 1976, Gene's doctors found that he had diabetes, in addition to his other ailments. They ordered him not to drink under any circumstances. Sherry tried her best to police him, but he simply would not comply. Besides, they were broke - the book advance was long gone-and drink took Gene out of his pain. Few of his honors paid off in cash. Jim Hughes and I, a "rescue committee" of two, got to work. I read in the Times that the University of Arizona had established a Center for Creative Photography in Tucson, for the purpose of preserving photographers' archives, and that they had acquired those of Ansel Adams. Knowing Ansel to be one of Gene's longtime friends and admirers, despite their different styles, I called him at his studio in Carmel, California. Ansel put me into touch with John Schaefer, president of the University of Arizona, and on Schaefer's next visit to New York we met in the office of attorney Arthur Soybel, who was negotiating Gene's divorce from Aileen. Schaefer said that he could appoint Smith to the faculty if Gene would donate his archives to the center - negatives, prints, correspondence, all the raw material of his working fife - as Ansel had. But he could keep his master prints to benefit his children. In exchange, Gene would be appointed professor, with a darkroom, assistants, and a $30,000 annual salary. In November, the movers left for Tucson with 44,000 pounds - 22 tons - of prints, negatives, contact prints, magazines, books, letters, file cabinets (dozens), desks, easy chairs, tapes, and phonograph records (thousands). Gene had saved everything, even old laundry lists and pawn tickets. One book carton, for example, held nothing but lens caps. When Gene arrived in Tucson he found a postcard from Ansel: "Congratulations ... I think I should come down and learn how to make a photograph." A few days later, feeling dizzy, Gene was advised to check into a hospital for tests. On the day he was due for release, he had a massive cerebral hemorrhage and went into a coma. Sherry immediately flew to Tucson, followed by Gene's children: Juanita from Oregon; Marissa, Shana, Patrick, and Patrick's wife, Phyllis, from New York; and Kevin from Berkeley, where he was finishing law school. It was the first time Kevin had met his siblings. Patrick had not even known of Kevin's existence: his sisters had only recently learned that Patrick was not the only son and had kept that fact from him. Gene remained in a coma into January. He had agreed to speak to the Copperstate Press Photographers at Arizona State University in Tempe on March 4. In February, it seemed obvious that he could not do it, so I agreed to appear in his place. I flew to Tucson on March 1, visiting him in the hospital that afternoon. To my astonishment I found Gene determined to go to Tempe. By the next day, he had his doctors talked into it, so Sherry arid I got him to a hotel in Tempe for the night and sneaked him into the auditorium the next day. We kept him backstage while I showed and discussed Smith's slides with his own taped commentary. Then I said, "I'm sure you all know why Gene couldn't make this talk himself today. He wanted so much to be here, but the president of the University of Arizona said no, his doctors said no, all common sense said no ... but ... here he is!" With this, Sherry wheeled Gene out from backstage. There was pandemonium as six hundred photographers and students cheered for ten minutes. Gene, unable to speak, could only wave, his eyes flooding tears. Amazingly, by summer Gene was sufficiently recovered to make a trip to New York to talk with a magazine editor about shooting a story on John Travolta. He then returned to Tucson, where he actually taught class for a few days. One Sunday morning he stole out of his house to buy a beer and collapsed on the floor of the neighborhood convenience store. He died soon after. From the mortuary I went to see John Schaefer and the university's principal attorney, who asked me what I thought the Smith estate was worth. Sherry had told me the night before that Gene had eighteen dollars in the bank and thousands of dollars in past due bills. Without hesitation, I replied, 'About a million dollars." They didn't blink. Sherry had also told me that Gene had vastly underestimated the number of his master prints. There were thousands, perhaps six thousand. It was all that Gene had to leave to his children, but I was determined to make them a small fortune. Three of the five children were desperately poor, their needs urgent. Things had changed since Gene's Magnum years, when we had been lucky to sell an occasional print for fifty dollars - not just Gene's but also those of Magnum "contributors" Edward Weston and Ansel Adams. Thanks in large part to Ansel Adams, Adams's business partner, William Turnage, and a few shrewd dealers, a market for photographic prints developed in the seventies. I am glad to say that by now sales of prints from the Smith estate have exceeded my original estimate. It was the creative side of the Smith legacy however, that presented the greatest challenge. I soon realized how enormously fortunate Gene had been in making his move to Tucson's Center for Creative Photography. I had to make a dozen or so trips to Tucson, and on most of them I worked with Smith's personal curator, W S. "Bill" Johnson. An experienced librarian and scholar, Bill dedicated himself to preserving the integrity of Smith's archive. In the spring of 1980, I went to Tucson for two weeks with Midge. She had been operated on for breast cancer, and we thought the change and sunshine would do her good. She had come to know Gene well in his last years - of us she was the one who had usually taken his calls for help. One day Bill Johnson told us over lunch of his dream of publishing a catalogue raisonné of the center's two thousand best Smith images. Midge immediately said, "Bill, just do it. Make us a rough dummy and we'll take it back to New York and sell it." He did, and we did. Michael Hoffman of Aperture, in what I termed "an act of faith," took on the project and obtained funding. Johnson's "W. Eugene Smith: Master of the Photo Essay" is a classic, unfortunately now out of print. In 1980, Howard Chapnick of Black Star spurred several friends of Gene's - the "rescue committee" had grown from two to five (we were joined by Jim Hughes, attorney Arthur Soybel, and ace camera repairman Martin Forscher) - to found the W. Eugene Smith Memorial Fund, meant to encourage "photographers who work in the tradition of W. Eugene Smith" to undertake concrete projects that need noncommercial support. Such grants, of $10,000 to $20,000, have been made every year since; photographers from ten countries have won so far, among them Jane Evelyn Atwood (the first recipient), Eugene Richards, Sebastião Salgado, Gilles Peress, Donna Ferrato, James Nachtwey, and Cristina Garcia Rodero. In 1980, Midge and I attended the annual Rencontres Internationales de la Photographie in Arles, where I had been invited to speak, in the great old Roman amphitheater, about "You-jenn" Smith. As at Tempe, I showed Cornell Capa's "images of Man" filmstrip on Gene, brilliantly edited by Sheila Turner Seed for Scholastic, with Gene's own commentary. The problem was to first play Gene's words, in his own voice, and then translate them, phrase by phrase, into French. Fortunately, I was given a translator who understood intuitively. We had time for only one rehearsal, but the show itself, with a thousand people watching in total silence, went perfectly. I added Gene's words, from the back cover of the Minamata book:

Midge died of cancer on July 9, 1981. She had lived just long enough to see, and to fully appreciate, the words that Bill Johnson chose to appear on the dedication page of his catalogue raisonné. He had kept it secret from her: FOR MIDGE MORRIS [end of quotes concerning William Eugene Smith and Aileen Mioko Sprauge Smith from the book "Get The Picture" by John Godfrey Morris] |

You are here - Minolta Photography: http://www.oocities.org/minoltaphotographyw/williameugenesmith02.html

Minolta Photography Home Page: http://www.minoltaphotography.com or http://www.oocities.org/minoltaphotography

Visitors count by http://www.digits.com

Designed for ~1024 x ~768 by ~16 bit/pixel color - your display is set for by bit/pixel color.

Adjust your screen brightness/contrast for 20 shades of black to white

This page updated Friday, June 28, 2002 5:51 AM