HISTORICAL SKETCH OF QUEENSLAND

Atlas Page 58

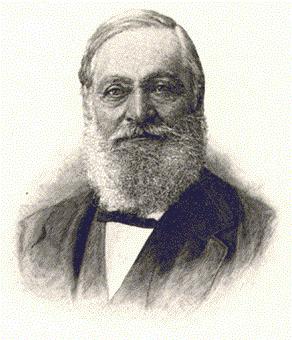

By W. H. Traill

LEICHHARDT’S SECOND JOURNEY.

MEANWHILE, however, the indefatigable Leichhardt had been

again bestirring himself. Little more than half a year after his reappearance in Sydney,

he was off again to Moreton Bay with the determination to start, as before, from the

Darling Downs and thence to traverse the continent from east to west, intending to make

for the settlement at Swan River on the Indian Ocean. Accordingly, in December, he started

from Jimbour station. He had eight companions, of whom Mr. Hovenden Hely, subsequently

distinguished as an explorer on his own account, was one. A flock of goats, two hundred

and seventy in number, ninety sheep, and forty head of cattle were driven before them by

the party. But the attempt proved a complete failure. Dissension broke out among the

explorers; probably there were too many equals. Almost certainly Leichhardt was a

difficult man to get on with; his own journal of his first expedition affords ample proof

of this.  As therein described by himself, he seems to have

been abstracted, moody, and unsociable. Anyhow, on this expedition much bad feeling arose

between him and his companions. The party was also fever-stricken. They had to abandon

their goats; they lost most of their bullocks and some of their horses and mules; in

short, further progress became impossible. They turned back, abandoning a portion of their

stores, and reappeared on the Condamine in a temper and a condition equally miserable,

having merely gone over Leichhardt’s old track as far as the Peak Downs.

As therein described by himself, he seems to have

been abstracted, moody, and unsociable. Anyhow, on this expedition much bad feeling arose

between him and his companions. The party was also fever-stricken. They had to abandon

their goats; they lost most of their bullocks and some of their horses and mules; in

short, further progress became impossible. They turned back, abandoning a portion of their

stores, and reappeared on the Condamine in a temper and a condition equally miserable,

having merely gone over Leichhardt’s old track as far as the Peak Downs.

By this time the report of Mitchell had been made public, and

Leichhardt, almost without resting, set off to inspect the country lying between his

original track and that of Sir Thomas, and especially to visit the Fitzroy Downs. This

seems to have been also an unsuccessful trip, and returning to Darling Downs he hastened

to Sydney to make fresh arrangements for his great transcontinental project. By the middle

of February, 1848, Leichhardt had completed all his preparations. His party, as

reconstituted, consisted of Mr. Classan, a connection of his own whom he had met while

last in Sydney, and who now took the position of second in command of the expedition a Mr.

Hentig; Donald Stuart, one of Patrick Leslie’s tried men, another man named Kelly,

and two native blacks. His stock consisted of fifty bullocks, thirteen mules, twelve

horses, and two hundred and seventy goats. He was provided with eight hundred pounds of

flour, one hundred and twenty pounds of tea, one hundred pounds of salt, two hundred and

fifty pounds of shot, and forty pounds of powder. His intention was to follow the track of

Mitchell from the sources near Mounts Abundance, Bindeygo, and Bindango —of the

Coogoon River, by the Maranoa, to the Victoria River; thence he proposed to launch out to

the westward. At a pastoral station, which had already been formed near Mount Abundance,

he wrote on April 14th, 1848, his farewell letter to Sydney; then, for the last time,

turning his back on the settlements, he marched into the silent wilderness, which shut him

and his companions off for evermore from the sight of their fellow-men. From that day to

the present hour the fate of Leichhardt has remained the dead secret of the Australian

interior. Of Leichhardt and his companions not a trace has ever since been found. Of his

flock of goats, of his horses and mules, of his bullocks, not a hoof or a horn has

certainly been seen. Forty years have, as we write, elapsed, and still the fate of the

lost explorers remains unrevealed. Even the icy fingers of the frozen North have been less

retentive than the secretive grasp of central Australia. The fate of Franklin has been

ascertained; the doom of Leichhardt no man knows.

EDMUND KENNEDY.

LITTLE more than a month after Leichhardt had penned the last words

which the world was ever to have from his hand, another expedition, also destined to have

a melancholy termination, was launching out in a different portion of what now constitutes

the territory of Queensland. The mighty peninsula, which terminates in Cape York, had

been, as regards its south-western base, partially traversed by Leichhardt in his first

expedition.

But its eastern side and its centre remained a terra incognita.

The home and colonial authorities were exercised at the time by the question as to whether

Cape York might not be preferable to Port Essington, or at any rate a desirable addition

to that post, as the locality for an establishment. In connection with this, the idea of

exploring the peninsula itself seems to have arisen. The enterprise was decided upon, and

in 1848 Edmund Kennedy was charged with the task for which his previous experience

distinctly qualified him. His party was conveyed by sea to Rockingham Bay, and there

landed. His mission was to make his way to the coast opposite All any Island at the apex

of the cape; there he was to be met and taken off by a schooner, which was sent for the

purpose. The journey proved laborious and unfortunate from the outset; the country to be

traversed was rugged and in every sense difficult. Of the eleven white men who accompanied

Kennedy, but a few were staunch and true. The carts with which the explorers were provided

had soon to be abandoned. Impeded by mountains and ravines, torn by dense tropical

jungles, through which every step had to be cut with axe and tomahawk; frequently worried

by hunger and tortured by thirst, haunted and harassed by bold and hostile natives,

progress was one continual struggle. Terribly exhausted, and with stores alarmingly

diminished owing to the necessary abandonments of portions when the drays were left

behind, and when horse after horse failed and fell, Kennedy emerged, after toiling over

five hundred miles of wilderness, upon the shores of Weymouth Bay. In the course of this

desperate journey, he must repeatedly have trodden wealth under his feet.  His

track carried him through the centre of what little more than a score of years later were

destined to be famous goldfields the Hodgkinson and the Palmer among others. It had become

obvious to Kennedy that with the whole party he could not hope to proceed farther. He took

three whites and his black fellow, Jacky Jacky, with horses, and pushed on, leaving the

remaining seven men under the charge of Mr. Carron, botanist and second in command, to

rest and recover until he should reach Albany and return to their rescue by sea.

Misfortune still pursued him. For food he had to sacrifice horses, and live on the smoked

flesh of these worn-out animals. And presently one of his companions, while carelessly

dragging his gun into the tent, shot himself, receiving a severe flesh wound. The case of

the little party was too desperate to permit of delays. Next day they again pushed

forward, but the sufferings of the wounded man became insupportable. Once more the unhappy

leader had to divide his party and sacrifice himself. At Shelburne Bay he left the wounded

man, with his two comrades to guard and tend him. Kennedy himself, with Jacky Jacky for

his sole companion, struggled forward, with all the speed his increasing weakness

permitted, to traverse the ninety miles or so which still separated him from Albany

Strait. His steps were dogged by the ferocious blacks, who had never ceased to follow and

menace his reduced party. Seven weary days and nights the two men —the white and the

black —struggled desperately on like haunted creatures, their impish attendants

hovering continually around them. Their horses were almost useless. One got bogged in a

swamp, and a whole day was vainly spent in the endeavour to extricate the feeble brute.

Then Jacky Jacky implored Mr. Kennedy to abandon the other wasted and leg-weary animals;

but Kennedy would not —nay, he could not —he was too weak to hope to reach his

goal without them. The blacks gibbered and scuttled around them. Every bush and every

rock, every creek and every scrub seemed peopled with demons. The haunted men could not,

even when night fell, sink to the ground and seek renewal of strength in sleep

—"Sweet nature’s soft restorer, balmy sleep." They dared not, when

darkness set in, light a fire and thus betray their position. They must needs drag on

their weary limbs yet apace, and hope to elude in the obscurity their keen eyed pursuers.

And even when at length they ventured to halt, it was to watch and slumber alternately,

each relieving the other every hour. At last-at last they saw the shining sea! Albany was

in sight, and salvation at hand! But one more night, and then a single day of struggle,

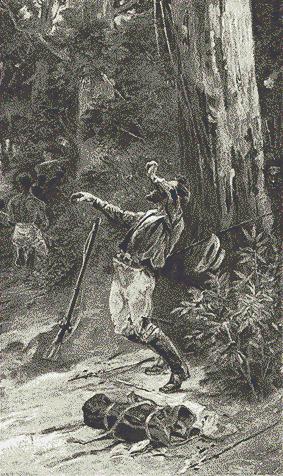

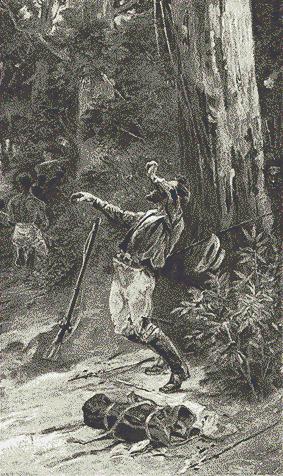

and they would be among their expectant waiting friends But the skulking foe had gathered

courage as the prey grew feebler. Kennedy, utterly worn out, was seated on the ground. In

front, on either side, and behind him the forest was filled with menace. The twigs were

crackling under sneaking feet. . Hideous faces protruded from behind tree trunks and

fallen logs. Jacky Jacky, gun in hand, stole out to execute a sortie, and create a

diversion. He warned his weary master to have a quick eye to see, and to keep looking,

around and behind. But poor Kennedy was afflicted with extreme shortness of sight at the

best of times. In his weakened condition, probably he could scarcely see at all. He did

not look behind. Like savage beasts, which the power of the human eye can control, the

savages seized their chance. A shower of spears was hurled from behind him. One pierced

his thigh, and another quivered in his back, and a third buried itself in his side. Jacky

Jacky ran to him. The prowling assassins skulked out of gunshot. Kennedy charged his

blackfellow to take his papers and save himself. He even asked for a pencil to write; but

it was too late.

His

track carried him through the centre of what little more than a score of years later were

destined to be famous goldfields the Hodgkinson and the Palmer among others. It had become

obvious to Kennedy that with the whole party he could not hope to proceed farther. He took

three whites and his black fellow, Jacky Jacky, with horses, and pushed on, leaving the

remaining seven men under the charge of Mr. Carron, botanist and second in command, to

rest and recover until he should reach Albany and return to their rescue by sea.

Misfortune still pursued him. For food he had to sacrifice horses, and live on the smoked

flesh of these worn-out animals. And presently one of his companions, while carelessly

dragging his gun into the tent, shot himself, receiving a severe flesh wound. The case of

the little party was too desperate to permit of delays. Next day they again pushed

forward, but the sufferings of the wounded man became insupportable. Once more the unhappy

leader had to divide his party and sacrifice himself. At Shelburne Bay he left the wounded

man, with his two comrades to guard and tend him. Kennedy himself, with Jacky Jacky for

his sole companion, struggled forward, with all the speed his increasing weakness

permitted, to traverse the ninety miles or so which still separated him from Albany

Strait. His steps were dogged by the ferocious blacks, who had never ceased to follow and

menace his reduced party. Seven weary days and nights the two men —the white and the

black —struggled desperately on like haunted creatures, their impish attendants

hovering continually around them. Their horses were almost useless. One got bogged in a

swamp, and a whole day was vainly spent in the endeavour to extricate the feeble brute.

Then Jacky Jacky implored Mr. Kennedy to abandon the other wasted and leg-weary animals;

but Kennedy would not —nay, he could not —he was too weak to hope to reach his

goal without them. The blacks gibbered and scuttled around them. Every bush and every

rock, every creek and every scrub seemed peopled with demons. The haunted men could not,

even when night fell, sink to the ground and seek renewal of strength in sleep

—"Sweet nature’s soft restorer, balmy sleep." They dared not, when

darkness set in, light a fire and thus betray their position. They must needs drag on

their weary limbs yet apace, and hope to elude in the obscurity their keen eyed pursuers.

And even when at length they ventured to halt, it was to watch and slumber alternately,

each relieving the other every hour. At last-at last they saw the shining sea! Albany was

in sight, and salvation at hand! But one more night, and then a single day of struggle,

and they would be among their expectant waiting friends But the skulking foe had gathered

courage as the prey grew feebler. Kennedy, utterly worn out, was seated on the ground. In

front, on either side, and behind him the forest was filled with menace. The twigs were

crackling under sneaking feet. . Hideous faces protruded from behind tree trunks and

fallen logs. Jacky Jacky, gun in hand, stole out to execute a sortie, and create a

diversion. He warned his weary master to have a quick eye to see, and to keep looking,

around and behind. But poor Kennedy was afflicted with extreme shortness of sight at the

best of times. In his weakened condition, probably he could scarcely see at all. He did

not look behind. Like savage beasts, which the power of the human eye can control, the

savages seized their chance. A shower of spears was hurled from behind him. One pierced

his thigh, and another quivered in his back, and a third buried itself in his side. Jacky

Jacky ran to him. The prowling assassins skulked out of gunshot. Kennedy charged his

blackfellow to take his papers and save himself. He even asked for a pencil to write; but

it was too late.  His clouding eyes assumed a curious look. "Oh,

Mr. Kennedy," cried Jacky Jacky, "don’t look so far away!" But the

soul of the explorer had followed his gaze to the mysterious far away. Poor Jacky Jacky

cried a good deal, and remained helplessly by his dead master till he "got

well." Then he made shift to bury the body after the best fashion he could; this done

he plunged into the bush, and fled for his life. The wild blacks hung upon his tracks.

Repeatedly, to elude their bloodthirsty pursuit, he slid silently into creeks and waded

long distances, his head only above the water. Only after fourteen days of such travel did

he reach the shore. The schooner was there. Her crew saw descending to the beach a

blackfellow in shirt and trousers. The boat received him —an emaciated care-worn

wretch, whose energies collapsed on the moment, and who sank, apparently expiring, in the

bottom of the boat.

His clouding eyes assumed a curious look. "Oh,

Mr. Kennedy," cried Jacky Jacky, "don’t look so far away!" But the

soul of the explorer had followed his gaze to the mysterious far away. Poor Jacky Jacky

cried a good deal, and remained helplessly by his dead master till he "got

well." Then he made shift to bury the body after the best fashion he could; this done

he plunged into the bush, and fled for his life. The wild blacks hung upon his tracks.

Repeatedly, to elude their bloodthirsty pursuit, he slid silently into creeks and waded

long distances, his head only above the water. Only after fourteen days of such travel did

he reach the shore. The schooner was there. Her crew saw descending to the beach a

blackfellow in shirt and trousers. The boat received him —an emaciated care-worn

wretch, whose energies collapsed on the moment, and who sank, apparently expiring, in the

bottom of the boat.

Tended and refreshed, his touching and melancholy narrative was soon

told. The anchor was weighed, and sail was made for Shelburne Bay, where the three white

men ad been left; there a canoe came off filled with natives. With singular effrontery,

they had with them spoils of the missing men, and even the trousers in which the corpse of

Kennedy had been clad when buried. Jacky Jacky recognised one of his master’s

murderers. The wretch was seized and bound. The other natives took the alarm and paddled

for the shore under a fire of musketry, which did some work; but in the night the captive

managed to loosen his bonds, slip overboard, and, by swimming, scathless reach the shore.

Sail was made for Weymouth Bay in the faint hope of rescuing the main

body of the expedition. There four of the crew landed, and led by Jacky Jacky arrived just

in time to witness a singular scene. Two enfeebled wretches were in the very act of

holding at bay a lot of cowardly blacks. The two men were too weak to stand —almost

too weak to sit upright altogether too weak to bring their guns to their shoulders. One

held his across his knees; the other steadied his piece on a sapling. All the rest were

dead. At the sight of the rescuing party the blacks sullenly retired. The two living men

were conveyed to the vessel; they had an awful history to relate. They had been harassed

by the blacks day and night ever since Kennedy quitted them. The tactics of their

persecutors had been incomprehensible. Early, these had brought the half-starved party a

tempting lot of fish, and made signs to them to come forth and enjoy it; the whites

suspected a trap, and abstained. Then they had showers of spears, sudden solitary attacks,

apparently commiserating doles of fish, and then attacks again. By spear wounds, by

hunger, by sleeplessness, and by continual deadly fear, they were destroyed one by one.

The dramatic attitude in which the last two were discovered by the rescuers was no casual

incident. It had been their posture, off and on, day after day. As cowardly as cruel, the

blacks had never dared to face them while in an attitude of watchfulness and defence. They

were simply harassing them to death-watching and waiting, night and day, for a chance to

steal on them unperceived, and slaughter them without risk to themselves. Thus ended

Kennedy’s last expedition. Of the twelve men whom he led forth, three returned to the

settlement. His own remains —but it is as painful as vain to contemplate their

dispersal; they can never be all collected. The spear-pierced corpse of the lion-hearted

explorer suffered a fate more revolting than befell the mangled body of Jezebel. There are

in the Australian bush human dogs more bestial than the curs of Samaria.

SUBSEQUENT EXPLORATION.

THE deplorable result of Kennedy’s expedition sharpened the anxiety

which had begun to be felt respecting the fate of Leichhardt. Persistent rumours had been

coming in from the frontier stations that some catastrophe had overtaken his party shortly

after their plunge into the wilderness. The natives told dismal but various stories, all

pointing to some misfortune. At length, in January, 1852, Hovenden Hely was despatched to

follow U the tracks of the expedition, and ascertain the facts if possible. He effected

next to nothing. From a tribe of blacks he heard a circumstantial narrative describing the

murder of Leichhardt and his whole party about one hundred miles northwest of Mount

Abundance; but another story attributed their destruction to a great flood which had swept

them all away. Hely, however, found two of their camps considerably farther to the

northwest than the scene of the alleged fatal inundation, but, his provisions running

short, he was compelled to beat a retreat to the settlement.

After this failure several years elapsed. Interest in the fate of

Leichhardt gradually dwindled. Mr. A. C. Gregory, indeed, in 1855, after extensive

explorations in northwest Australia, crossed the base of Arnhem’s Peninsula, and

reached the Roper River in the Gulf of Carpentaria, whence he journeyed partly along the

course of Leichhardt’s first expedition in the Carpentarian country, and, following

up the Lynd, crossed to the Burdekin, traced that river down to the Belyando, ascending

which he made his way by the Suttor and Mackenzie to a station on the lower Dawson.

But in 1857 the memory of the lost

explorers was suddenly and vividly reawakened by a curious episode. A convict, named

Garbut, communicated to his custodians a queer story. He had been a frontier bushman, and

he alleged that he was willing to purchase his liberty by disclosing a secret of momentous

interest. He had, he stated, visited, far beyond the outposts of settlement, in the heart

of the continent, a colony of absconders from the old penal establishments. There, in a

rich and well-watered tract, these runaways had established themselves —their numbers

grown considerable by successive arrivals of runaways. They had married native women, and

lived in peace and plenty. Communication was maintained with the settlements by means of

packhorses. Thus the absconder colonists obtained not only implements and necessaries of

European manufacture, but even luxuries. The position of this extraordinary community

Garbut indicated to be some two hundred miles to the north-east of Hely’s farthest.

The most startling part of his story was that Leichhardt and his companions were living,

unwilling guests, detained by the people of this colony. The explorer had come upon their

retreat, and, lest he should disclose their secret to the authorities, he and his whole

expedition were compelled to abide. This romance momentarily created strong excitement;

but discussion and reflection speedily exposed its improbabilities. Nevertheless, the

emotion created was probably the essential influence in promoting the organisation of a

new expedition in search of traces of Leichhardt. Mr. Gregory was entrusted with the

leadership, and, starting from Juandah Station on the upper Dawson, he effectually

exploded the fictions of Garbut by passing through the alleged location of the

absconders’ paradise. On Mitchell’s Victoria River (the Barcoo) Mr. Gregory

found, eighty miles beyond Hovenden Hely’s farthest exploration, a tree marked L,

with traces of a camp of Europeans. It has been doubted whether this was, as he

conjectured, a camp of Leichhardt’s, or one of Kennedy’s, when the latter was

following up the explorations of Mitchell. Kennedy’s fiftieth camp was supposed to

have been somewhere in this vicinity, and the L might be the Roman numeral instead of the

initial of Leichhardt’s name. Pursuing their north-westerly course, Gregory and his

eight companions struck the Alice, and ran it down to its junction with the Thomson. The

latter they endeavoured to follow upwards in the direction which Leichhardt might have

been expected to proceed; but defeated in this purpose by want of water, they retraced

their steps, and like Kennedy worked downwards towards Cooper’s Creek. The journey

was dismal and monotonous. The river spread into an infinity of channels, and every token

showed that in flood time a whole territory was inundated. Mr. Gregory considered that the

floods would lay the country under many feet of water across a tract not less than eighty

miles in width. When he traversed it, this depressed area was dry and barren; its monotony

oppressed, and its desolation appalled. At Cooper’s Creek the scattered channels

temporarily united, and fine reaches of water existed; continuing southward, again the

channel branched into numerous divisions. Occasionally they ran out altogether on flats or

plains where no special depression could be distinguished. By this time Gregory was in the

territory of South Australia. Tracing the channel known as Strzelecki’s Creek, he was

by it guided to the desolate and saline banks of Lake Torrens. Thence the intrepid

explorers had no trouble in reaching Adelaide, where they were received with enthusiasm.

But in 1857 the memory of the lost

explorers was suddenly and vividly reawakened by a curious episode. A convict, named

Garbut, communicated to his custodians a queer story. He had been a frontier bushman, and

he alleged that he was willing to purchase his liberty by disclosing a secret of momentous

interest. He had, he stated, visited, far beyond the outposts of settlement, in the heart

of the continent, a colony of absconders from the old penal establishments. There, in a

rich and well-watered tract, these runaways had established themselves —their numbers

grown considerable by successive arrivals of runaways. They had married native women, and

lived in peace and plenty. Communication was maintained with the settlements by means of

packhorses. Thus the absconder colonists obtained not only implements and necessaries of

European manufacture, but even luxuries. The position of this extraordinary community

Garbut indicated to be some two hundred miles to the north-east of Hely’s farthest.

The most startling part of his story was that Leichhardt and his companions were living,

unwilling guests, detained by the people of this colony. The explorer had come upon their

retreat, and, lest he should disclose their secret to the authorities, he and his whole

expedition were compelled to abide. This romance momentarily created strong excitement;

but discussion and reflection speedily exposed its improbabilities. Nevertheless, the

emotion created was probably the essential influence in promoting the organisation of a

new expedition in search of traces of Leichhardt. Mr. Gregory was entrusted with the

leadership, and, starting from Juandah Station on the upper Dawson, he effectually

exploded the fictions of Garbut by passing through the alleged location of the

absconders’ paradise. On Mitchell’s Victoria River (the Barcoo) Mr. Gregory

found, eighty miles beyond Hovenden Hely’s farthest exploration, a tree marked L,

with traces of a camp of Europeans. It has been doubted whether this was, as he

conjectured, a camp of Leichhardt’s, or one of Kennedy’s, when the latter was

following up the explorations of Mitchell. Kennedy’s fiftieth camp was supposed to

have been somewhere in this vicinity, and the L might be the Roman numeral instead of the

initial of Leichhardt’s name. Pursuing their north-westerly course, Gregory and his

eight companions struck the Alice, and ran it down to its junction with the Thomson. The

latter they endeavoured to follow upwards in the direction which Leichhardt might have

been expected to proceed; but defeated in this purpose by want of water, they retraced

their steps, and like Kennedy worked downwards towards Cooper’s Creek. The journey

was dismal and monotonous. The river spread into an infinity of channels, and every token

showed that in flood time a whole territory was inundated. Mr. Gregory considered that the

floods would lay the country under many feet of water across a tract not less than eighty

miles in width. When he traversed it, this depressed area was dry and barren; its monotony

oppressed, and its desolation appalled. At Cooper’s Creek the scattered channels

temporarily united, and fine reaches of water existed; continuing southward, again the

channel branched into numerous divisions. Occasionally they ran out altogether on flats or

plains where no special depression could be distinguished. By this time Gregory was in the

territory of South Australia. Tracing the channel known as Strzelecki’s Creek, he was

by it guided to the desolate and saline banks of Lake Torrens. Thence the intrepid

explorers had no trouble in reaching Adelaide, where they were received with enthusiasm.

It would be wearisome to recount in detail all the explorations from

this time forward. With the exception of the extreme easterly portion of the colony and

the north-westerly part of York’s Peninsula, the entire territory had been threaded

with a tracery of explorers’ routes which left little scope for the imagination. The

day of illimitable distances and boundless expanses was nearly over; pastoral settlement

was spreading and extending in every direction. It had become a profitable enterprise to

push on in advance, explore, and define in detail tracts of country suitable for runs, and

sell the information to stockowners desirous of establishing new stations. The journals

and reports of the earlier explorers were eagerly studied, and where, within accessible

distance from the rapidly advancing frontier line of occupation, tracts of rich country

were indicated in these documents, hardy bushmen pushed out little expeditions of their

own, and buried themselves in the interior for months at a time.

They travelled on until they found a stretch of attractive country, and

then they traversed it in every direction, exploring tributary creeks, locating lagoons

and water holes, and roughly mapping the whole. On their return to the settlements they

applied for leases of the areas thus defined, and these leases were marketable

commodities. In 1858-9 William Landsborough in this fashion explored in detail a

considerable stretch of territory on the Isaacs and the Suttor; George Elphinstone

Dalrymple organised an expedition by land, and ran down the Burdekin towards the sea,

while a hired schooner sailed up the coast to meet him at Upstart Bay. In the following

years the hot-headed and unfortunate Burke crossed and recrossed the only portion of the

colony which remained untraversed —the extreme west —from Cooper’s Creek to

the Gulf of Carpentaria, and three relief expeditions, simultaneously launched from

starting-places widely apart, to rescue him or ascertain his fate, added considerably to

the knowledge of the interior. Of these, the expedition under M’Kinley, with whom was

W. O. Hodgkinson, started from the south, skirting Sturt’s Desert, where in flooded

country such as Gregory had traversed, in the same neighbourhood, they found in native

camps some goats’ hair —relics of Leichhardt’s flock. Thence the party

pushed on northward, and, passing successively Middleton’s, Hamilton’s, and

Warburton’s Creeks, crossed or skirted in the following order the ranges now known as

Crozier’s, Williams’, Kirby’s, and Sarah’s; the last named they

observed to be metalliferous. Pursuing their course by the Marchant, Williams’, and

Poole’s Creeks, they descended on the Cloncurry River, and reached the coast through

the Plains of Promise, where they found Captain Norman, R.N., on the river Albert with

H.M.S. "Victoria," and the wreck of the tender "Firefly" moored as a

hulk in the river.

These vessels had conveyed the expedition under Mr. Landsborough,

disembarking it near the juncture of the Barclay and Albert. Landsborough proceeded to

scour the adjacent country, and followed up the Albert for one hundred and twenty miles,

seeing no traces of the missing explorers. Returning to his starting-point, he found that

M’Kinley and Walker had previously arrived there.cont...

click here to return to main page

As therein described by himself, he seems to have

been abstracted, moody, and unsociable. Anyhow, on this expedition much bad feeling arose

between him and his companions. The party was also fever-stricken. They had to abandon

their goats; they lost most of their bullocks and some of their horses and mules; in

short, further progress became impossible. They turned back, abandoning a portion of their

stores, and reappeared on the Condamine in a temper and a condition equally miserable,

having merely gone over Leichhardt’s old track as far as the Peak Downs.

As therein described by himself, he seems to have

been abstracted, moody, and unsociable. Anyhow, on this expedition much bad feeling arose

between him and his companions. The party was also fever-stricken. They had to abandon

their goats; they lost most of their bullocks and some of their horses and mules; in

short, further progress became impossible. They turned back, abandoning a portion of their

stores, and reappeared on the Condamine in a temper and a condition equally miserable,

having merely gone over Leichhardt’s old track as far as the Peak Downs. His

track carried him through the centre of what little more than a score of years later were

destined to be famous goldfields the Hodgkinson and the Palmer among others. It had become

obvious to Kennedy that with the whole party he could not hope to proceed farther. He took

three whites and his black fellow, Jacky Jacky, with horses, and pushed on, leaving the

remaining seven men under the charge of Mr. Carron, botanist and second in command, to

rest and recover until he should reach Albany and return to their rescue by sea.

Misfortune still pursued him. For food he had to sacrifice horses, and live on the smoked

flesh of these worn-out animals. And presently one of his companions, while carelessly

dragging his gun into the tent, shot himself, receiving a severe flesh wound. The case of

the little party was too desperate to permit of delays. Next day they again pushed

forward, but the sufferings of the wounded man became insupportable. Once more the unhappy

leader had to divide his party and sacrifice himself. At Shelburne Bay he left the wounded

man, with his two comrades to guard and tend him. Kennedy himself, with Jacky Jacky for

his sole companion, struggled forward, with all the speed his increasing weakness

permitted, to traverse the ninety miles or so which still separated him from Albany

Strait. His steps were dogged by the ferocious blacks, who had never ceased to follow and

menace his reduced party. Seven weary days and nights the two men —the white and the

black —struggled desperately on like haunted creatures, their impish attendants

hovering continually around them. Their horses were almost useless. One got bogged in a

swamp, and a whole day was vainly spent in the endeavour to extricate the feeble brute.

Then Jacky Jacky implored Mr. Kennedy to abandon the other wasted and leg-weary animals;

but Kennedy would not —nay, he could not —he was too weak to hope to reach his

goal without them. The blacks gibbered and scuttled around them. Every bush and every

rock, every creek and every scrub seemed peopled with demons. The haunted men could not,

even when night fell, sink to the ground and seek renewal of strength in sleep

—"Sweet nature’s soft restorer, balmy sleep." They dared not, when

darkness set in, light a fire and thus betray their position. They must needs drag on

their weary limbs yet apace, and hope to elude in the obscurity their keen eyed pursuers.

And even when at length they ventured to halt, it was to watch and slumber alternately,

each relieving the other every hour. At last-at last they saw the shining sea! Albany was

in sight, and salvation at hand! But one more night, and then a single day of struggle,

and they would be among their expectant waiting friends But the skulking foe had gathered

courage as the prey grew feebler. Kennedy, utterly worn out, was seated on the ground. In

front, on either side, and behind him the forest was filled with menace. The twigs were

crackling under sneaking feet. . Hideous faces protruded from behind tree trunks and

fallen logs. Jacky Jacky, gun in hand, stole out to execute a sortie, and create a

diversion. He warned his weary master to have a quick eye to see, and to keep looking,

around and behind. But poor Kennedy was afflicted with extreme shortness of sight at the

best of times. In his weakened condition, probably he could scarcely see at all. He did

not look behind. Like savage beasts, which the power of the human eye can control, the

savages seized their chance. A shower of spears was hurled from behind him. One pierced

his thigh, and another quivered in his back, and a third buried itself in his side. Jacky

Jacky ran to him. The prowling assassins skulked out of gunshot. Kennedy charged his

blackfellow to take his papers and save himself. He even asked for a pencil to write; but

it was too late.

His

track carried him through the centre of what little more than a score of years later were

destined to be famous goldfields the Hodgkinson and the Palmer among others. It had become

obvious to Kennedy that with the whole party he could not hope to proceed farther. He took

three whites and his black fellow, Jacky Jacky, with horses, and pushed on, leaving the

remaining seven men under the charge of Mr. Carron, botanist and second in command, to

rest and recover until he should reach Albany and return to their rescue by sea.

Misfortune still pursued him. For food he had to sacrifice horses, and live on the smoked

flesh of these worn-out animals. And presently one of his companions, while carelessly

dragging his gun into the tent, shot himself, receiving a severe flesh wound. The case of

the little party was too desperate to permit of delays. Next day they again pushed

forward, but the sufferings of the wounded man became insupportable. Once more the unhappy

leader had to divide his party and sacrifice himself. At Shelburne Bay he left the wounded

man, with his two comrades to guard and tend him. Kennedy himself, with Jacky Jacky for

his sole companion, struggled forward, with all the speed his increasing weakness

permitted, to traverse the ninety miles or so which still separated him from Albany

Strait. His steps were dogged by the ferocious blacks, who had never ceased to follow and

menace his reduced party. Seven weary days and nights the two men —the white and the

black —struggled desperately on like haunted creatures, their impish attendants

hovering continually around them. Their horses were almost useless. One got bogged in a

swamp, and a whole day was vainly spent in the endeavour to extricate the feeble brute.

Then Jacky Jacky implored Mr. Kennedy to abandon the other wasted and leg-weary animals;

but Kennedy would not —nay, he could not —he was too weak to hope to reach his

goal without them. The blacks gibbered and scuttled around them. Every bush and every

rock, every creek and every scrub seemed peopled with demons. The haunted men could not,

even when night fell, sink to the ground and seek renewal of strength in sleep

—"Sweet nature’s soft restorer, balmy sleep." They dared not, when

darkness set in, light a fire and thus betray their position. They must needs drag on

their weary limbs yet apace, and hope to elude in the obscurity their keen eyed pursuers.

And even when at length they ventured to halt, it was to watch and slumber alternately,

each relieving the other every hour. At last-at last they saw the shining sea! Albany was

in sight, and salvation at hand! But one more night, and then a single day of struggle,

and they would be among their expectant waiting friends But the skulking foe had gathered

courage as the prey grew feebler. Kennedy, utterly worn out, was seated on the ground. In

front, on either side, and behind him the forest was filled with menace. The twigs were

crackling under sneaking feet. . Hideous faces protruded from behind tree trunks and

fallen logs. Jacky Jacky, gun in hand, stole out to execute a sortie, and create a

diversion. He warned his weary master to have a quick eye to see, and to keep looking,

around and behind. But poor Kennedy was afflicted with extreme shortness of sight at the

best of times. In his weakened condition, probably he could scarcely see at all. He did

not look behind. Like savage beasts, which the power of the human eye can control, the

savages seized their chance. A shower of spears was hurled from behind him. One pierced

his thigh, and another quivered in his back, and a third buried itself in his side. Jacky

Jacky ran to him. The prowling assassins skulked out of gunshot. Kennedy charged his

blackfellow to take his papers and save himself. He even asked for a pencil to write; but

it was too late.  His clouding eyes assumed a curious look. "Oh,

Mr. Kennedy," cried Jacky Jacky, "don’t look so far away!" But the

soul of the explorer had followed his gaze to the mysterious far away. Poor Jacky Jacky

cried a good deal, and remained helplessly by his dead master till he "got

well." Then he made shift to bury the body after the best fashion he could; this done

he plunged into the bush, and fled for his life. The wild blacks hung upon his tracks.

Repeatedly, to elude their bloodthirsty pursuit, he slid silently into creeks and waded

long distances, his head only above the water. Only after fourteen days of such travel did

he reach the shore. The schooner was there. Her crew saw descending to the beach a

blackfellow in shirt and trousers. The boat received him —an emaciated care-worn

wretch, whose energies collapsed on the moment, and who sank, apparently expiring, in the

bottom of the boat.

His clouding eyes assumed a curious look. "Oh,

Mr. Kennedy," cried Jacky Jacky, "don’t look so far away!" But the

soul of the explorer had followed his gaze to the mysterious far away. Poor Jacky Jacky

cried a good deal, and remained helplessly by his dead master till he "got

well." Then he made shift to bury the body after the best fashion he could; this done

he plunged into the bush, and fled for his life. The wild blacks hung upon his tracks.

Repeatedly, to elude their bloodthirsty pursuit, he slid silently into creeks and waded

long distances, his head only above the water. Only after fourteen days of such travel did

he reach the shore. The schooner was there. Her crew saw descending to the beach a

blackfellow in shirt and trousers. The boat received him —an emaciated care-worn

wretch, whose energies collapsed on the moment, and who sank, apparently expiring, in the

bottom of the boat.