Since 1994, the Liverpool excavation of the Late Bronze Age fortress at Zawiyet Umm el-Rakham has clarified earlier findings and revealed much more of the plan of the settlement and evidence of the activities that took place there. It has shown the fortress to be much larger than previously assumed (c.20,000m2), as well as establishing that it was founded in, and abandoned during or shortly after the reign of Ramesses II (c.1278-1212BC) and confirming the position of Neb-Re as its "commandant" for at least part of its lifespan.

To learn about the work at ZUR, read on, or for information on a specific area of the site, click it on the rough plan below of the fort as of 2000:

| Temple and chapels | |

| Storage Magazines | Libyan squatter occupation |

| Residential Complex | Southern Building |

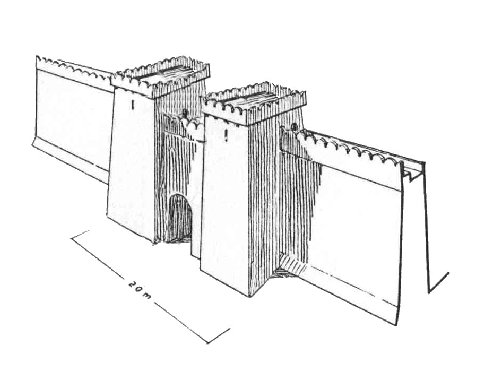

The fortress' mud-brick enclosure wall is 4-5m thick with the added defence of a plastered glacis at its base (Snape 1998:1082). The glacis was a slope at the bottom of the wall (see fig iii below), intended to make the walls more difficult to scale, which at about 10m tall would have been a formidable challenge in any case.

Further work on the gateway that Habachi located and labelled "Gate B" (fig.i) indicates that it was the site's main entrance, forming a limestone-clad corridor gateway (Snape 1997:23); how Habachi's "Gate A" relates to this is as yet undetermined. There were massive mud-brick towers on either side of the gate with internal chambers.

The picture below (fig.ii) show how the western tower looked when excavated. The red outlines the original extent of the mud-brick wall and tower. The yellow outlines the remains of the limestone floor of the internal chamber within the tower and wall, whilst the blue lines mark either end of the cladding of the gateway (as shown in fig.i above).

Below (fig.iii) is a reconstruction of another fortified gateway giving an impression of what that at Zawiyet Umm el-Rakham would have looked like:

In addition to those inscriptions Habachi (1955:65, 1980:16) described upon the gateway, an inscription on the eastern side refers to "the fortresses upon the hill-country of Tjemeh and the wells which are within them" (Snape 1998:1083). This makes it clear that Zawiyet Umm el-Rakham was not the only fortress in the region, established as being the territory of the Tjemeh Libyan group. It also states that within the forts were water sources and indeed, in 1999, a well was located within the enclosure, opposite the storage magazines, inscribed with the name of Ramesses II and still containing (admittedly grim looking) water.

The initial season of work at the site concentrated on clearing and recording the limestone temple originally located by Habachi in the 1950s (Giddy 1994:28; Snape 1997:23-24). Significant deterioration had occurred in the years since the temple was first uncovered, the limestone blocks having been eroded by the region's seasonal rains and sandstorms. The contrast in preservation between the lower courses of blocks that have only recently been exposed and those higher up which were uncovered in the 1950s is plain to see below (fig.iv).

To the front of the temple there were once pylons (towers), flanking the entrance and typical of temples of the period. However, almost all of these were removed during Roman activity at the site leaving behind little but a few sherds of Roman pottery (Snape pers com; 2002).

To the south of the temple lay three small chapels. These are fronted by a courtyard, and a covered portico originally shaded their entrance, of which only the supporting column bases remained (fig.v). Earlier work here in the 1950s had seen the removal of parts of the chapels' doorjambs and several stelae, which had originally sat at the back of the chapels. However, the deposits within remained essentially intact and their excavation was supervised by Dr Penny Wilson. It has been suggested that these were private chapels intended for the worship of the deified Ramesses II (Giddy 1996:27; Snape 1997:24).

Although the northernmost chapel was empty, the two most southerly chapels produced a range of pottery, both local and imported wares, including Canaanite amphorae, Aegean coarse-ware stirrup-jars and Cypriot base-ring juglets, which would have been used to transport such commodities as olive oil, wine and opium (Snape 1997:24, 1998:1082), as well as artefacts including an incense burner and its stand (fig.vii).

In 2000, with work in this area all but over, there was the unexpected discovery of a smaller, second temple to the east of the chapels. Built from rough, local limestone (much of which had been robbed-out in Roman times, like the main temple pylons), the new temple was small, 10x5m, and consisted of two courtyards in front of a group of three small rooms, presumably sanctuaries, at the rear of the structure, with inscribed doorways naming the deities Ptah and Sekhmet (Giddy 2001:28; Snape 2001:19, 2001b).

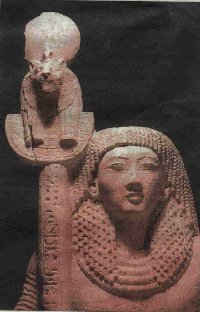

From the southernmost of the chapels came a stunning cache of monuments. These included a stone naos with integral statues of Ptah and Sekhmet, two large stelae showing Neb-Re, the fort commander, making offerings to various gods, and a beautiful 2/3 life-size limestone statue of Neb-Re holding a standard with the head of Sekhmet (figs.ix, x, xi). Both the goddess Sekhmet and her consort Ptah seem to have been favourites at ZUR, and this emphasis on the patron deities of Memphis suggests the possibility that the regiments manning this fortress may have originated from this city (Snape ibid.).

The very fine nature of the statue of Neb-Re suggests that it is a product of the late 18th Dynasty, a period of impressive private statuary, atypical of the rest of the Ramesside period (Snape 2001b). This has been taken to indicate that the fortress may have been founded early in the reign of Ramesses II.

On all of the monuments, Neb-Re's name and image has been chiselled out, leaving only a faint impression, although they are otherwise undamaged, which might suggest they were awaiting re-use (Snape 2001b). Dr Snape (2001:19) has postulated that Neb-Re may have come to regard this region, distant from the heart of the Egyptian empire and the king, as his "own personal fiefdom", and was ultimately disgraced and replaced for assuming titles and powers beyond his station. Maybe further excavation will shed more light on Neb-Re's fate.

|

|

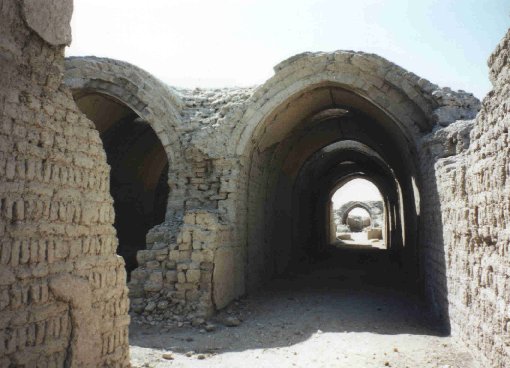

In 1995, work began on a series of nine storage magazines running north from the temple (Snape 1997:24, 1998:1082). These are approximately 16m long by 2m wide, and originally had limestone doorways bearing the names and titles of Ramesses II (figs.xii, xiii). The fifth magazine had a lintel depicting a kneeling Neb-Re, the fort's commandant, worshipping Ramesses' cartouches (Snape ibid).

Interestingly, the doorjambs bear a form of the name of Ramesses II that is only used very early in his reign, suggesting that the fort was an early project for the new king (Kitchen 1999:331). This supports speculation discussed above that the fort was founded early in Ramesses' reign.

Although a majority of the magazines were empty, the first produced a range of non-Egyptian, East Mediterranean pottery of a similar range to that located in the chapels (Snape 1997:24, 1998:1082). Whilst these finds might represent nothing more than part of the fortresses' state supplied provisions, it is possible that they could be somewhat more significant.

The pottery compares closely with material found on Bates' Island at Marsa Matruh, 20km eastwards along the coast from Zawiyet Umm el-Rakham. It has been proposed that this site acted as a trading post or revictualing point for Late Bronze Age mariners sailing the Mediterranean trade routes via the North African coast (Conwell 1987; Hulin 1989; White 1985, 1986a, 1986b, 1987, 1989, 1990a, 1990b, 1999b). Could the fortress finds indicate that it too played some role in the Late Bronze Age trade network? Click here for more information on this.