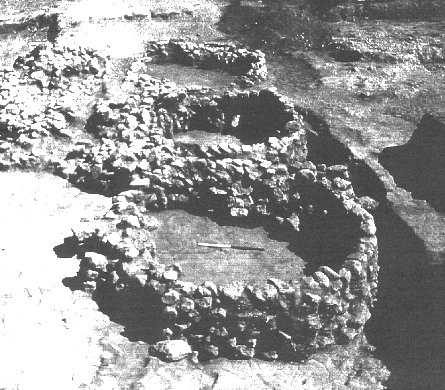

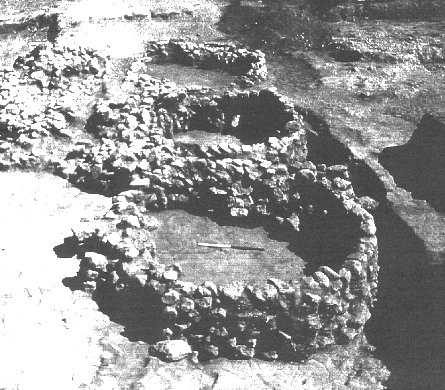

Near to the fort's magazines, a number of rough, stone-built circular features were located (fig.xvi). It was thought at first that these may have been the fort's granaries, but their distance from the residential area, located in the south-eastern corner of the site, and the absence of any grain remains or a suitable lining has led to this idea being discounted.

It now seems likely that the features might indicate a phase of Libyan squatter occupation (Giddy 1998:29). Once abandoned by the Egyptians, the fort must have been a very enticing location for a camp, being secure and having its own water supply. The features are certainly of a secondary occupation phase as one partially blocks the entrance to the first magazine. The fact that they spoil the impressive fašade originally offered by the limestone doorways of the magazines and clutter up the courtyard in front also suggests that they were not part of the original plan. That they might be of Libyan origin is indicated by the rough construction method and certain associated finds of a low technological quality, such as rough clay beads, neither of which are Egyptian in nature.

Exactly what the features are, however, is not known. Some potential parallels have been found to the west on Seal Island, off the coast of Cyrenaica. These circular features were described by Oric Bates (1914:246-248) and by T.H. Carter (1963:25-27), and they were identified as local Libyan graves. Whilst no evidence of burials has been found in the structures at Zawiyet Umm el-Rakham, there are similarities beyond just shape. Bates (1914:248) noted that almost no material was found within the Seal Island graves and that the majority of finds came from outside the superstructure. This is also the case at Zawiyet Umm el-Rakham where a great deal of material has been found around the outside of the features but nothing inside. Alternatively, there is a suggestion that they might have been animal pens, with the modern Bedouin using similar structures (Simpson pers com).

In 1998, what now appears to be the main residential area of the fortress was located. Partial excavation of this large area in 1999 revealed it consisted of small 3-4 room houses clustered around communal ovens, where baking and brewing would have taken place (Giddy 2000:32).

Large quantities of pottery were discovered, including beer and water jars, drinking cups, amphorae and further fragments of Aegean wares. In addition, various ancient Egyptian domestic appliances were found including fragments of numerous quern stones, of both the saddle and tripod varieties, which would have been used for grinding grain. Where this grain was stored is yet to be determined as the site's granaries remain undetected.

To find the granaries would be very useful, as this would allow a rough estimate of the fort's population to be gauged from the quantity of grain that could have been stored within. From what we know about other similar forts, however, it is likely that abut 500 men were stationed here, this being two garrisons (Charters 2000:19; Snape 2001b)

The final notable structure within the fortress enclosure is a building on the southern side that, for want of a better name, has been titled the Southern Building.

This is a very unusual stone-built structure, unparalleled in Egyptian architecture. Originally two storied, much of the lower level survives along with numerous stone elements inscribed with the names of Ramesses II and Neb-Re, although none of these remain in situ (Snape 2001:19). This may, at different times have served as a place of worship for non-Egyptians and/or Neb-Re's residence (one room contains a bath and pedestal toilet!) (Snape 2001b).

At the front of the building is a courtyard off of which lead three long hallways, in each of which were found a single standing stone, c.2m high (fig.xx). These have rounded tops which indicates that they were not support pillars. Around their bases a great deal of pottery had been deposited seemingly as some form of offering. This led to the suggestion that the structure was of a sacred nature.

Standing stones were sometimes sacred for the ancient Egyptians, but were never worshipped in the manner apparently seen here. Some potential parallels have been pointed out however, such as the "massebah" temples of certain sites in Palestine, for example Beth-Shan (Rowe 1930:11, 1940:4). The worship of columns and other standing stones is also known in contemporary Aegean religion (Nilsson 1927:201-224; Renfrew 1985:430-1). Although we know nothing of Late Bronze Age Libyan religious practices, it is conceivable that they may too have worshipped standing stones. Why might ZUR contain a structure designed as a place of worship for non-Egyptians? Perhaps this is linked to the fort's position on the Mediterranean coast, once traveled by mariners following Late Bronze Age trade routes. This possibility is discussed in more depth later.

Within the building, two lintels were discovered showing Neb-Re sitting alongside a woman, Mery-Ptah, probably his wife (fig.xx). Although damaged, the text inscribed upon this stonework is typically found on mortuary monuments, such as tombs (Snape 2001:19, 2001b). Could this indicate that Neb-Re built/planned to build a tomb somewhere nearby? If so, what might this suggest about the length of time Neb-Re served/intended to serve at the fort?

Whatever the case, one of the two lintels was found face down, reused as a doorstep during remodeling of the building (Snape ibid.). This again suggests a fall from grace for Neb-Re, as discussed previously.

Dr Snape claims he has "a wide range of wild scenarios about the bizarre history of South Building" but is keeping them under his hat until wok on the structure is completed. No excavation took place here in 2001 or 2002, but work in 2003 may further illuminate the function of this structure.