Harold J. McKenzie attended the Harvard Business School's Advanced Management Program in 1950. Many times this would lead to a promotion. He was the T.& N.O.'s first representative, and he never dreamed that, from his job as chief engineer, he would be chosen for a high executive position on another railroad. In late November, he received a phone call from New York.

Harold J. McKenzie attended the Harvard Business School's Advanced Management Program in 1950. Many times this would lead to a promotion. He was the T.& N.O.'s first representative, and he never dreamed that, from his job as chief engineer, he would be chosen for a high executive position on another railroad. In late November, he received a phone call from New York.

Mr. A. T. Mercier and Mr. D. J. Russell called Mr McKenzie telling him that January 1, 1951, he would be promoted to Executive Vice President of the Cotton Belt Railroad, headquartered in St. Louis, Missouri. Surprise and initial shock were soon followed by the realization that he had never been on the Cotton Belt Railroad! He did know that the Cotton Belt was a subsidiary of the Southern Pacific, serving as its gateway to the northern and eastern parts of the United States. Mr· Mercier and Mr. Russell had not asked if he would care to move to St. Louis and take the job, but they had known he would.

Afterwards, he spent nights in the Harvard Business School Library (one of the best railroad sections in the country) reading everything he could find about the Cotton Belt. He wanted to know what he was getting into.

He left Harvard on December 8, 1950, and spent the remainder of the month organizing the T.& N.O. chief engineer's office. He began moving his books and personal belongings out of the S.P. Building.

Mac had a son, sixteen and a daughter, thirteen so he decided that he would first go to St. Louis, find a place to live, a school for the children, and then move the family and belongings before mid term. Following this plan, the McKenzies found the move itself hectic, but the breaking away from relatives and friends of half a century was worse!

The McKenzies were met by the most miserable weather they had ever experienced. That winter was one of the worst on record. During their move, a thirteen inch snowstorm covered the area for more than a month!

The McKenzie's found a home in Clayton (just north of Forest Park), one of the ninety-two municipalities surrounding St. Louis. A two-story brick with a basement that served as garage, laundry, heating plant, and storage. Shortly after the move, Mrs. McKenzie stalled her new Buick in the ice and snow next to the house as she entered the steep driveway.

LOOKING OVER HIS NEW DOMAIN

As the business car "Fair Lane" went over the railroad night or day, the superintendent and his assistant had to be on the car in their respective territories. When the car was set out for the night at the various terminals, everything was done but "to call out the band." All local officers would report to the car while mechanics and special agents patrolled the area around the car continuously. Colonel Green and Mr. Mac took automobile trips to inspect local facilities and to meet shippers in each area.

The Cotton Belt, at this time, had its general offices in St. Louis and division headquarters in Pine Bluff, Arkansas and Tyler, Texas. The Northern Division, the part of the railroad north of Texarkana, had 964 track miles of main and branch lines and headquarters in Pine Bluff. South of the state line at Texarkana was the St. Louis Southwestern Railway Company of Texas, a Texas corporation, generally called the Southern Division with headquarters at Tyler and 611 miles of track. Of this total of 1,575 miles of track, about fifteen percent was leased or used under operating rights.

PASSENGER SERVICE DISCONTINUED

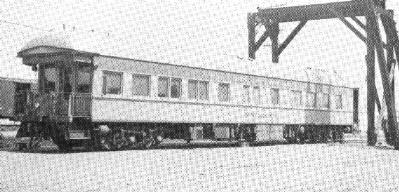

One of the hardest tasks in Mr. Mac's tenure was to discontinue passenger service which later proved practical and profitable to the Cotton Belt. In the forties, the C.B. had secured several lightweight passenger chair-cars. It had two passenger diesels and seven other diesel units that could handle either freight or passenger trains. The railroad made every effort to take care of the passenger business, while people were still riding trains. With the advent of better highways, fast, comfortable automobiles, passenger traffic dwindled to a only few on each run, most traveling on passes.

Cotton Belt was losing about $4 million a year on passenger trains, which was bad in itself, but with the loss of the mail to busses and trucks then to airlines, very little revenue was left. The Cotton Belt was some ten years ahead of other railroads on the removal of passenger trains.

Before the all-out program of eliminating passenger trains, three trains were discontinued: Corsicana-Waco in December 1947; motor train, TylerLufkin in November 1949; and Memphis-Brinkley in October 1950. The decision was made to discontinue the remaining trains by districts, over a period of seven or eight years. This proved to be a better plan than going "whole hog", upsetting communities and railroad people with a whirlwind move. Having the opportunity to observe the affects of each and acquiring records for the next hearing before the I.C.C. and State Commissions was an added benefit, as was the readjustment of train and engine crews in various districts.

The close-out program began in August 1951, with Mount Pleasant-Corsicana and continued to November 1959. The annual reduction in passenger train miles was approximately 1,400,000. The cost for just the operation of these trains averaged about three dollars per mile-or $4,200,000!

NEAR COLLISION

A SPECIAL passenger train of officials including Mr. Mac were on a trip from St. Louis to Pine Bluff when at the North Switch of the McKinney passing track 'all hell broke loose'!

The train was approaching the passing track at a speed of sixty-five miles per hour when a road foremen in the cab of the lead unit saw a GREEN Signal ahead at the pass but the main line switch was lined for the pass. He hollered at the engineer who immediately put the brakes in emergency, but they entered the turnout where the maximum allowable was only thirty miles per hour.

Mr. Russell's business car was on the rear of the train where he was observing the railroad as we went over the line. Mac was sitting behind him when the brakes went into emergency. We both looked out the window at the frontview mirror and saw all the cars, rocking back and forth as they went through the open switch. The track and turnout were in excellent condition, and none of the cars derailed. HOWEVER -- there was a short freight train in the south end of the passing track. Fortunately, the engineer brought the train to a stop before having a rear-end collision. No one was injured, no damage was done to the track or to the equipment, but it was one of the most embarrassing incidents that happened to Mr Mac in his entire railroad career.

after arriving in Tyler -- they contacted the chief engineer, the signal engineer, and all concerned for an immediate inspection, halting all trains at McKinney until the trouble was corrected. This was the only false 'clear' signal indication ever had on the Cotton Belt railroad.

AN investigation revealed that the maintainer who had been working on the remote control switch that morning had reversed one of the electric relays and failed to properly reconnect it, thus causing the green light to be ON in the signal, with the switch points OPEN to the passing track.