Karamjeet Singh's Himalayan Home

Part fantasy, part reality ....... Ladakh, is where, the forces of nature conspired to render a

magical realist landscape ..... a landscape of extremes ..... desert and blue waters,...

burning sun and freezing winds,... glaciers and sand dunes ..... a primeaval battleground of

the titanic forces which gave birth to the Himalayas.

Ladakh means "land of high passes". Until the coming of the aircraft, the only access into this remote,

high Trans-Himalayan kingdom, was across several high and dangerous pass crossings. From the west the

Zoji la at 14,000 feet is the lowest. Taglang la to the south east is 17,200 feet high and a military highway

now crosses this coming from Manali. To the north is the Khardung la - at 18,200 feet, the only access

into the Nubra valley and the Karakorums. Dead ends now, but important in centuries past, were the

northern passes on the Central Asian trade route - Saser la and the Karakorum pass.

Ladakh's landscape has more in common with the lunar landscape than any other place on earth. Being

in a complete rainshadow region, cut off from the monsoon clouds by the Great Himalaya and a host of

subsidiary ranges, it is a cold high altitude desert where the wind, water from the minimal winter snows, and chemical reactions within the rocks themselves, have carved a fantastic, sometimes grotesque,

landscape.

and chemical reactions within the rocks themselves, have carved a fantastic, sometimes grotesque,

landscape.

Even though Ladakh gets very little snow the winters are intensely cold with temperatures of -30

degrees common in most parts. Some places get even colder. Dras, in Kargil district, has the unique

distinction of being the coldest inhabited town in the world. Peak winter temperatures can hover near -

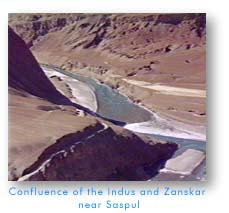

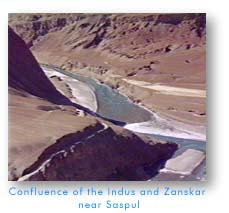

50 degrees for days at a time. Everything in Ladakh freezes - the Indus and Zanskar become broad

highways of ice, and the Great lakes, Pangong and Tso Morari, freeze to a depth of several metres.

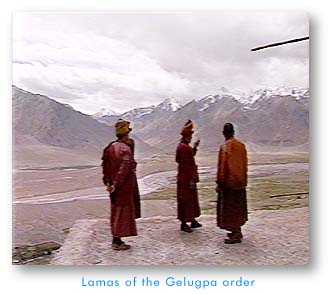

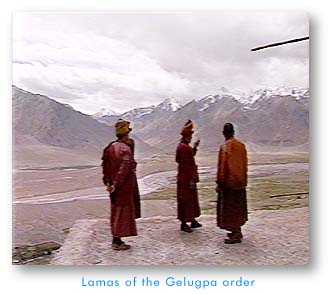

The bleakness and austerity of the landscape combined with the inaccessibility probably contributed a

lot to the development of Ladakh's unique Buddhist culture, where generations of monks in fairy tale  monasteries have developed philosophical concepts devolving around silence and emptiness, as well as

a world renowned tradition of religous art.

monasteries have developed philosophical concepts devolving around silence and emptiness, as well as

a world renowned tradition of religous art.

The monastic tradition is itself the result of the tradition of meditating in remote or secluded places,

common to all religions in India at the time. In Ladakh, caves were a natural choice and the majority are

associated with Buddhist yogins who are believed to have meditated in them at certain times. Later,

these became the nuclei around which monasteries grew. At the heart of the famous Lamayuru gompa,

is the cave of Naropa. Naropa, an Indian sage, begat an illustrious lineage. His disciple was Marpa,

whose disciple in turn, was the greatest ascetic of them all - Milarepa. It bears mentioning that modern

historians are more inclined to place Naropa's hermitage in the North of Bihar - 1500 kms to the east.

Lamayuru has certainly seen better days however. The 17th century, under the rule of the great Ladakhi

king Senge Namgyal, was the golden age with hundreds of resident lamas and with donations from a

munificient king and court rolling in.

these became the nuclei around which monasteries grew. At the heart of the famous Lamayuru gompa,

is the cave of Naropa. Naropa, an Indian sage, begat an illustrious lineage. His disciple was Marpa,

whose disciple in turn, was the greatest ascetic of them all - Milarepa. It bears mentioning that modern

historians are more inclined to place Naropa's hermitage in the North of Bihar - 1500 kms to the east.

Lamayuru has certainly seen better days however. The 17th century, under the rule of the great Ladakhi

king Senge Namgyal, was the golden age with hundreds of resident lamas and with donations from a

munificient king and court rolling in.

Earlier, in the 11th century, the Great Translator Rinchen Tsangpo came to Ladakh from the Tibetan kingdom of Guge. To the

modern world a title like the Great Translator may seem pompous but nevertheless he is one of the most revered figures

in Ladakh, Spiti and Tibet, for it was Rinchen who translated the words of the Sakyamuni Buddha from the Sanskrit and

Pali canons to Tibetan. Many of these texts comprise the scriptures - the Kanjur and the associated commentaries written

by Indian masters - the Tenjur. In fact it is certain that many works long since lost in the original sanskrit, are well preserved

in the Tibetan translations done by Rinchen Tsangpo. I think it says a lot for the Buddhist peoples of the Trans Himalaya

that while they have no Great Leader or Great Warrior, they do have a Great Translator! An incomplete set of the

scriptures, lettered with pure gold and silver, is housed in the mysterious gompa of Shimrey.

Rinchen Tsangpo is also credited with introducing the arts of image making, wood carving and fresco painting, to Ladakh

and Spiti. It is his disciples who built the Alchi Choskhor, or religous enclave, now recognised as an artistic and heritage

site of global importance, no less than Michealangelo's Sistine chapel. Alchi represents a rare survival, it's 800 year old

murals and giant Boddhisatva figures covering every inch of wall space. Even the carved woodwork on the exterior is in

remarkably good shape, probably due to the dessicated climate. Whereas some parts have been retouched in the 16th century,

even in the unrestored portions, the colours are as bright as if painted the day before, the pigments preserved by the

near total absence of sunlight in the interiors. Sometime in it's history, for unknown reasons, Alchi was abandoned as a

living center of worship and this too contributed in no small measure too it's survival. Nowadays, the essential religous

functions are carried out by two monks on deputation from Likhir gompa.

The people of Ladakh are pretty unique too. Ladakhis have long had the reputation of being the friendliest and most hospitable

of people. This may have something to do with the fact that if you lived in these barren and inhospitable surroundings,

any new face, even a stranger, is more than welcome. So devoid is the landscape of any apparent life that one even feels

kindlily disposed to the occasional lizard one sights. This aspect of their make-up, combined with their Buddhist religion

makes the Ladakhis a very tolerant, inoffensive and non-violent people, not to mention , extremely hospitable. The kitchen

is the main living area of the Ladakhi home, for obvious reasons. The stove is also a central heating apparatus cum magnificient

centerpiece.

Getting there

Leh, the capital at 10,800 feet, is connected by air with Delhi and Srinagar. Indian Airlines is your best bet for regular

scheduling and reliable service. The sector is usually heavily booked throughout the year so reservations have to be

made well in advance.

Getting in to Leh is easier than getting out, for flights are often cancelled due to cloud cover in the valley. Landing in

Leh is quite an experience, for not only is the airfield at 11,000 feet above sea level, but also involves a turn within

the valley.The aircraft finally clips past the monastery of Spitok to land on a runway actually sloping down!

Getting in to Leh is easier than getting out, for flights are often cancelled due to cloud cover in the valley. Landing in

Leh is quite an experience, for not only is the airfield at 11,000 feet above sea level, but also involves a turn within

the valley.The aircraft finally clips past the monastery of Spitok to land on a runway actually sloping down!

If you fly in from Delhi via Chandigarh, the route takes you straight across the Parvati valley, over Indrasan and Deo Tibba,

to finally cross the Great Himalaya over the Kunzum pass. Beyond is the TransHimalaya, and soon the great lake Tso Morari

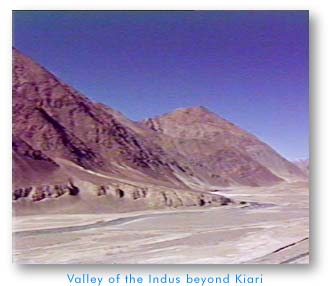

can be seen, an azure jewel amidst the auburn landscape. Beyond, the aircraft meets up with the valley of the Indus,

which it follows till Leh.

Coming in via Srinagar offers some sensational views of Nun and Kun, both twenty four thousanders,

after which come the deeply shadowed gorges of Zanskar. From above Parkachik the plane banks to the right and crossing

the Zanskar range, meets up with the valley of the Indus.

By road too there are two alternatives - a 500 kilometer drive in from Srinagar via the Zoji la and Kargil, and another 500

km drive from Manali via the Baralacha la and the Tanglang la. Both are fascinating but in my opinion the Manali-Leh stretch

has a definite edge. Besides the high pass crossings - Baralacha la is 16,400 feet and the Tanglang la is a breathtaking

17,200 feet- the route brings one through a fantasy landscape in western Lahaul where trolls and ogres would be appropriate

inhabitants. Further on, before the Tanglang la, are the More plains - a 100 plus kilometers of absolutely level grassland at nearly

17,000 feet. Here one can often spot a herd of Kyang - the Ladakhi wild ass.

By road too there are two alternatives - a 500 kilometer drive in from Srinagar via the Zoji la and Kargil, and another 500

km drive from Manali via the Baralacha la and the Tanglang la. Both are fascinating but in my opinion the Manali-Leh stretch

has a definite edge. Besides the high pass crossings - Baralacha la is 16,400 feet and the Tanglang la is a breathtaking

17,200 feet- the route brings one through a fantasy landscape in western Lahaul where trolls and ogres would be appropriate

inhabitants. Further on, before the Tanglang la, are the More plains - a 100 plus kilometers of absolutely level grassland at nearly

17,000 feet. Here one can often spot a herd of Kyang - the Ladakhi wild ass.

Once in Leh, if you've flown in, you need to acclimatise for at least 1 day, preferrably more. This is because, from the aircraft

with a cabin pressure set at near abouts sea level, you emerge straight at 11,000 feet. Non acclimatisation could lead

to an attack of high altitude pulmonary oedema (HAPO) which is fatal unless treated. In earlier days one would have to be

flown out immediately, but for the last two decades the Military Hospital has been equipped with decompression chambers,

where you are kept till the lungs are clear of fluid. If you drive in you have already acclimatised en route and are quite safe.

Once in Leh, if you've flown in, you need to acclimatise for at least 1 day, preferrably more. This is because, from the aircraft

with a cabin pressure set at near abouts sea level, you emerge straight at 11,000 feet. Non acclimatisation could lead

to an attack of high altitude pulmonary oedema (HAPO) which is fatal unless treated. In earlier days one would have to be

flown out immediately, but for the last two decades the Military Hospital has been equipped with decompression chambers,

where you are kept till the lungs are clear of fluid. If you drive in you have already acclimatised en route and are quite safe.

Now that inner line restrictions have been withdrawn from most of Ladakh, a variety of destinations are open to you. You

can drive north, across the 18,200 foot Khardung la into the Nubra and Shyok valleys. Towards the east, you can do a great

circle of the great lakes and the Changthang plateau before making it back to Leh. The route takes you via the 17,500 foot

Chang la pass and a fascinating 80 km cross country stretch along the Pangong Lake, to Chushul. From here we return to the valley of the Indus

via the Dungti trap, take a short detour via the equally magnificient Tso Morari lake, and return back to Leh. Make sure you take

a cross country vehicle on this one. Thirdly, you could around the Indus valley on a tour of most of the important monasteries.

Hemis, Shimrey, Thikse, Phyiang, Basgo, Likhir, Rezong, Alchi and Lamayuru are all more or less in a straight line along the Indus

valley.

|

|

Ladakh 2

|

This page hosted by

Get your own Free Home Page

Get your own Free Home Page

Web Page Design and Images Copyrightę: Karamjeet Singh

and chemical reactions within the rocks themselves, have carved a fantastic, sometimes grotesque,

landscape.

and chemical reactions within the rocks themselves, have carved a fantastic, sometimes grotesque,

landscape. monasteries have developed philosophical concepts devolving around silence and emptiness, as well as

a world renowned tradition of religous art.

monasteries have developed philosophical concepts devolving around silence and emptiness, as well as

a world renowned tradition of religous art. these became the nuclei around which monasteries grew. At the heart of the famous Lamayuru gompa,

is the cave of Naropa. Naropa, an Indian sage, begat an illustrious lineage. His disciple was Marpa,

whose disciple in turn, was the greatest ascetic of them all - Milarepa. It bears mentioning that modern

historians are more inclined to place Naropa's hermitage in the North of Bihar - 1500 kms to the east.

Lamayuru has certainly seen better days however. The 17th century, under the rule of the great Ladakhi

king Senge Namgyal, was the golden age with hundreds of resident lamas and with donations from a

munificient king and court rolling in.

these became the nuclei around which monasteries grew. At the heart of the famous Lamayuru gompa,

is the cave of Naropa. Naropa, an Indian sage, begat an illustrious lineage. His disciple was Marpa,

whose disciple in turn, was the greatest ascetic of them all - Milarepa. It bears mentioning that modern

historians are more inclined to place Naropa's hermitage in the North of Bihar - 1500 kms to the east.

Lamayuru has certainly seen better days however. The 17th century, under the rule of the great Ladakhi

king Senge Namgyal, was the golden age with hundreds of resident lamas and with donations from a

munificient king and court rolling in.

Getting in to Leh is easier than getting out, for flights are often cancelled due to cloud cover in the valley. Landing in

Leh is quite an experience, for not only is the airfield at 11,000 feet above sea level, but also involves a turn within

the valley.The aircraft finally clips past the monastery of Spitok to land on a runway actually sloping down!

Getting in to Leh is easier than getting out, for flights are often cancelled due to cloud cover in the valley. Landing in

Leh is quite an experience, for not only is the airfield at 11,000 feet above sea level, but also involves a turn within

the valley.The aircraft finally clips past the monastery of Spitok to land on a runway actually sloping down!

By road too there are two alternatives - a 500 kilometer drive in from Srinagar via the Zoji la and Kargil, and another 500

km drive from Manali via the Baralacha la and the Tanglang la. Both are fascinating but in my opinion the Manali-Leh stretch

has a definite edge. Besides the high pass crossings - Baralacha la is 16,400 feet and the Tanglang la is a breathtaking

17,200 feet- the route brings one through a fantasy landscape in western Lahaul where trolls and ogres would be appropriate

inhabitants. Further on, before the Tanglang la, are the More plains - a 100 plus kilometers of absolutely level grassland at nearly

17,000 feet. Here one can often spot a herd of Kyang - the Ladakhi wild ass.

By road too there are two alternatives - a 500 kilometer drive in from Srinagar via the Zoji la and Kargil, and another 500

km drive from Manali via the Baralacha la and the Tanglang la. Both are fascinating but in my opinion the Manali-Leh stretch

has a definite edge. Besides the high pass crossings - Baralacha la is 16,400 feet and the Tanglang la is a breathtaking

17,200 feet- the route brings one through a fantasy landscape in western Lahaul where trolls and ogres would be appropriate

inhabitants. Further on, before the Tanglang la, are the More plains - a 100 plus kilometers of absolutely level grassland at nearly

17,000 feet. Here one can often spot a herd of Kyang - the Ladakhi wild ass. Once in Leh, if you've flown in, you need to acclimatise for at least 1 day, preferrably more. This is because, from the aircraft

with a cabin pressure set at near abouts sea level, you emerge straight at 11,000 feet. Non acclimatisation could lead

to an attack of high altitude pulmonary oedema (HAPO) which is fatal unless treated. In earlier days one would have to be

flown out immediately, but for the last two decades the Military Hospital has been equipped with decompression chambers,

where you are kept till the lungs are clear of fluid. If you drive in you have already acclimatised en route and are quite safe.

Once in Leh, if you've flown in, you need to acclimatise for at least 1 day, preferrably more. This is because, from the aircraft

with a cabin pressure set at near abouts sea level, you emerge straight at 11,000 feet. Non acclimatisation could lead

to an attack of high altitude pulmonary oedema (HAPO) which is fatal unless treated. In earlier days one would have to be

flown out immediately, but for the last two decades the Military Hospital has been equipped with decompression chambers,

where you are kept till the lungs are clear of fluid. If you drive in you have already acclimatised en route and are quite safe.