Karamjeet Singh's Himalayan Home

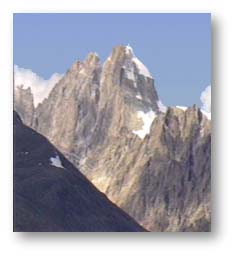

The roll call of great peaks continues as the great Himalaya continues it's march

southeastward through Lahaul and Spiti... Menthosa, Lord Gephan, The Gangstang

peaks and glaciers and onto the Chandrabhaga group... gorges,chasms,hanging glaciers

......a landscape for the strong of heart and adventurous of spirit.

The roll call of great peaks continues as the great Himalaya continues it's march

southeastward through Lahaul and Spiti... Menthosa, Lord Gephan, The Gangstang

peaks and glaciers and onto the Chandrabhaga group... gorges,chasms,hanging glaciers

......a landscape for the strong of heart and adventurous of spirit.

Lahaul is the land that time forgot........ a place where man and vegetation have had little opportunity

to change what is essentially an ice age landscape. Completely hemmed in by high ranges,

Lahaul has few points of entry and exit. To the northwest the Chandrabhaga has

gouged a near impassable gorge. The pass crossings are high and lead mainly into the

other Transhimalayan areas. There are only three main passes connecting Lahaul with the

lower hills... the Kugti leading to the Chamba valley, the well known Rohtang leading to

the Kulu valley and the Hampta, a trekkers delight, also leading to the Kulu valley.

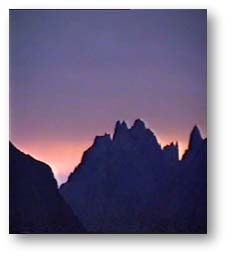

Crossing over from the Rohtang pass can be a shock ... a sudden transition from the verdant cedar forested slopes of the

Pangi-Pir Panjaal to the bleakness of the Lahaul landscape. A landscape that makes one feel like

Tolkien's Hobbit, adrift in the dark lands of Mordor ... a barren scree covered wilderness surrounded by towering

battlements of rock and ice, up which the twilight shadows creep, black as if painted on. Above them, the

crenellations and spires of the sorceror's castle stand silhouetted against the darkening sky. In the side valleys,

evil looking, snaggle toothed small glaciers hang, poised, and everywhere the howling dervishes that inhabit

the west wind, attempt to tear away your clothes. Batal, at the foot of the Kunzum pass and jump off point for the Bara-Shigri

glacier, is at only 11,000 feet the windiest place I have ever come across in my Himalayan travels. The savagery of the

winters can be gauged from the three bridges at Batal. One in use and the other two, mere ruins. The only other structure

is a PWD rest house with the roof gone and the walls going.

Crossing over from the Rohtang pass can be a shock ... a sudden transition from the verdant cedar forested slopes of the

Pangi-Pir Panjaal to the bleakness of the Lahaul landscape. A landscape that makes one feel like

Tolkien's Hobbit, adrift in the dark lands of Mordor ... a barren scree covered wilderness surrounded by towering

battlements of rock and ice, up which the twilight shadows creep, black as if painted on. Above them, the

crenellations and spires of the sorceror's castle stand silhouetted against the darkening sky. In the side valleys,

evil looking, snaggle toothed small glaciers hang, poised, and everywhere the howling dervishes that inhabit

the west wind, attempt to tear away your clothes. Batal, at the foot of the Kunzum pass and jump off point for the Bara-Shigri

glacier, is at only 11,000 feet the windiest place I have ever come across in my Himalayan travels. The savagery of the

winters can be gauged from the three bridges at Batal. One in use and the other two, mere ruins. The only other structure

is a PWD rest house with the roof gone and the walls going.

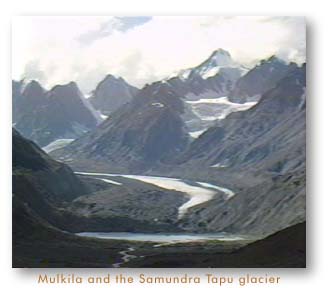

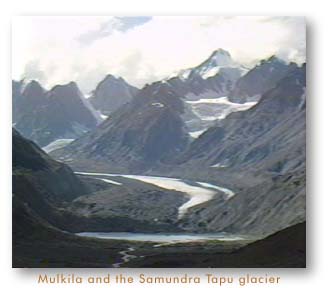

Lahaul and Spiti have probably the largest deposits of ice, next to the Karakorum, in the Indian Himalaya, and indeed

the entire landscape has been sculpted by ice and the omnipresent wind. These regions are in fact a 3-dimensional lesson

in geology with their exposed rock and millenia old ice documenting the days when the Himalayas were very young. In Lahaul.

between the two rivers, the Chandra and the Bhaga, lies the great bastion of the Chandrabhaga or C.B group of peaks,

a solid mass of convoluted rock and ice, a fortress encircling some of the most forbidding terrain on earth.

Opening out onto the Chandra valley, and adding it's waters to it, is the greater or Bara Shigri glacier, a frozen river of ice

nearly 28 kilometers long and several kilometers wide at it's widest. All around are the great peaks of the Parvati headwaters - White

Sail, Indrasan and further up the range, Kulu Makalu and Parbati peak itself.

Opening out onto the Chandra valley, and adding it's waters to it, is the greater or Bara Shigri glacier, a frozen river of ice

nearly 28 kilometers long and several kilometers wide at it's widest. All around are the great peaks of the Parvati headwaters - White

Sail, Indrasan and further up the range, Kulu Makalu and Parbati peak itself.

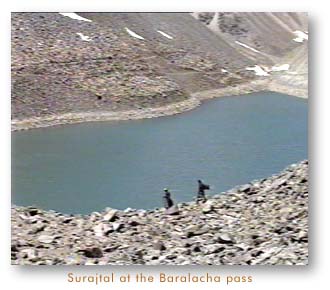

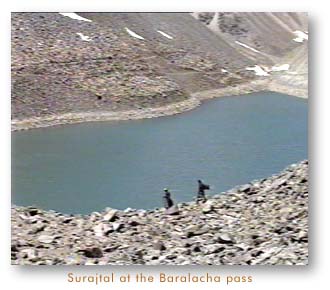

Towards the north-west, at an altitude of 16,400 feet, is the unique 8 kilometers long Baralacha pass, literally the pass "where many roads meet". Baralacha is one of the famous passes of Himalayan history, for here paths from Zanskar, Ladakh and Lahaul meet, and over the centuries

travellers have crossed in all directions. The two great rivers of Lahaul, the Chandra and the Bhaga also arise from the huge

snowfields on opposite sides of the pass. The Chandra then does a circuitious journey through Lahaul, picking up the waters

of the Samundra Tapu and Bara Shigri glaciers on the way, to finally meet up with the Bhaga at Tandi - forming the celebrated

Chandrabhaga.

is one of the famous passes of Himalayan history, for here paths from Zanskar, Ladakh and Lahaul meet, and over the centuries

travellers have crossed in all directions. The two great rivers of Lahaul, the Chandra and the Bhaga also arise from the huge

snowfields on opposite sides of the pass. The Chandra then does a circuitious journey through Lahaul, picking up the waters

of the Samundra Tapu and Bara Shigri glaciers on the way, to finally meet up with the Bhaga at Tandi - forming the celebrated

Chandrabhaga.

Within the cradle of the Bara Shigri and Samundra Tapu glaciers, lies the surreally beautiful Chandratal lake. The period after

the last major ice age was probably when Chandratal lake was formed, when the glaciers receded leaving behind considerable

dead ice masses trapped in the ice polished landscape. A landscape composed of the oldest core materials in the whole

Himalayas, crystalline rock, maybe 2,000 million years old.

If the landscape in Lahaul does'nt satisfy your spirit of adventure, there is always Spiti, higher in general elevation and if

possible, more rugged and difficult, terrain wise. Spiti is veritably ringed by a wall of 6,000 meter high peaks riven by an incredible landscape

of some of the deepest gorges and canyons on earth, with vertical ramparts plummeting thousands of feet. From Lahaul, the main access

to Spiti is across the 15,500 feet high Kunzum pass. Climatically also, Spiti provides little respite with winter tempratures as

low as -30 degrees centigrade and relentlessly cold winds all year round.

Lahoul and Spiti probably have India's lowest population density, alongwith Zanskar, and habitation is concentrated at a few

points along the main river valley. Western Lahaul being lower and greener, has most of the population, with the upper Chandra

valley having the least. Sometimes important points on the map turn out to be nothing but an abandoned rest house belonging

to the Public Works Dept and a signboard. Many years back I was doing a trek across the Hampta pass from Kulu. After the pass

crossing we were to descend into Lahoul to meet up with the motor road at Chotadara. For days, while trekking, we looked forward to Chota dara-

we didn't expect a metropolis but we did expect a village, a tea shop, maybe some cigarettes. What we found was a rest house

whose supposed attendant could'nt be located and the most unique signboard I have ever seen. It identified the place as indeed

being Chotadara and below that it said: Population - 0.

Lahaul is partly Hindu, partly Buddhist and partly, a mixture of both. Nowhere is this better symbolised than at the temple

of Trilokinath near Tandi in western Lahaul, where the idol worshipped as Lord Shiva by the Hindu populace, is venerated as the Buddha

Avilokateshwara by the local Buddhists, as well as pilgrims from Spiti and Ladakh. A few kilometers further up, where the Miyar

Nala meets the Chandrabhaga, lies the temple of Mrikula Devi at Udaipur. A wooden temple built by the Chamba kings in the

6th century A.D, it is ascribed to Gugga - the Michealangelo of the Himalaya. It's interiors are liberally embellished with

exquisite wooden carving that ecelectically display scenes from the Mahabharata and the Ramayana, all interspersed with

scenes from the Buddhist cosmology. The Buddha gives battle to Mara the tempter side by side with Lord Ram as he engages

Ravana. The enshrined goddess, Kali, venerated as Mrikula Devi, is worshipped as Dorje-phag-mo by the Buddhists.

Lahaul is partly Hindu, partly Buddhist and partly, a mixture of both. Nowhere is this better symbolised than at the temple

of Trilokinath near Tandi in western Lahaul, where the idol worshipped as Lord Shiva by the Hindu populace, is venerated as the Buddha

Avilokateshwara by the local Buddhists, as well as pilgrims from Spiti and Ladakh. A few kilometers further up, where the Miyar

Nala meets the Chandrabhaga, lies the temple of Mrikula Devi at Udaipur. A wooden temple built by the Chamba kings in the

6th century A.D, it is ascribed to Gugga - the Michealangelo of the Himalaya. It's interiors are liberally embellished with

exquisite wooden carving that ecelectically display scenes from the Mahabharata and the Ramayana, all interspersed with

scenes from the Buddhist cosmology. The Buddha gives battle to Mara the tempter side by side with Lord Ram as he engages

Ravana. The enshrined goddess, Kali, venerated as Mrikula Devi, is worshipped as Dorje-phag-mo by the Buddhists.

Spiti due to it's strategic location was for long closed to tourists except the odd intrepid traveller armed with an 'inner line'

permit. Recently, it has been thrown open for tourism and hitherto insulated cultures are coming into contact with jeep safaris

and video toting tourists. The numbers are still mercifully small though and Spiti offers a fast vanishing look at 'museum'

cultures, especially in the off-route Pin valley.

Spiti due to it's strategic location was for long closed to tourists except the odd intrepid traveller armed with an 'inner line'

permit. Recently, it has been thrown open for tourism and hitherto insulated cultures are coming into contact with jeep safaris

and video toting tourists. The numbers are still mercifully small though and Spiti offers a fast vanishing look at 'museum'

cultures, especially in the off-route Pin valley.

At the head of the Pin valley lies the Pin-Parbati pass leading into the Parvati valley. Desolate, remote and uninhabited

the Pin river National Park lies at the head of the most important tributary of the Spiti. With large parts under permanent

snow cover, the park is home to many of the larger mammals including the Snow Leopard and the Ibex. The Ibex, Capra ibex

sibirica, is well adapted for the extreme environment making it a fascinating, if extremely difficult to get at, study. A thick

winter coat helps against the intense cold whereas the summer coat is a thinner dark brown. Ibex seem to cultivate danger

frolicking on the most hazardous of slopes with gay abandon, and to all indications, spend their winter on steep cliffs that

are highly prone to avalanches. In fact unlike other Himalayan animals the Ibex does not descend in the winter and remain at

the sub-arctic regions above the summer snow line. No wonder then, that it has been estimated that winter avalanches

account for as much as 10% of the population over an average winter.

The Pin valley is also home to the Buzhen, wandering minstrel lamas who move from village to village enacting

comedies, miracle plays and singing ballads. During the bleak and harsh Spitian winter, they make their colourful way through

the monochromatic landscape entertaining the populations of far flung villages.

The Pin valley is also home to the Buzhen, wandering minstrel lamas who move from village to village enacting

comedies, miracle plays and singing ballads. During the bleak and harsh Spitian winter, they make their colourful way through

the monochromatic landscape entertaining the populations of far flung villages.

Unlike neighbouring Kinnaur and Lahaul where polyandrical practices were in vogue,

Spiti evolved different means of dealing with the twin problems of limited arable land

and an expanding population. A system of primogeniture where the eldest son takes all

is prevalent. The eldest daughter gets all the mother's jewellery. The younger

siblings have to fend for themselves and can always fall back upon the social security

system of the Transhimalayas... the monasteries and the nunneries.

Spiti is totally Buddhist and is the location of some of Himalayan Buddhism's most important monasteries. Tabo, known as the "Ajanta

of the Himalayas', celebrated it's thousandth birthday last year. Built by the Great Translator Rinchen Tsangpo, Tabo is, from the

exterior, the least imposing of the Himalayan Gompas that I have seen. Tabo doesn't crown some lofty pinnacle, instead it's mud plastered

buildings almost merge into the valley floor. The interiors are a different story altogether. In one dark hall, life size stucco

figurines, mounted some 6 feet off the floor, leer at you out of the gloom. The uncanny effect is enhanced by the perfect

detailing, of these gods and demons of the Tibetan pantheon. Some of the figures are clothed in fine fabrics, now decaying with

the passage of time. Elsewhere are numerous statues of varying sizes, some huge, entire spaces lined with exquisite miniature panels

depicting the thousand Buddhas and many others.

Spiti is totally Buddhist and is the location of some of Himalayan Buddhism's most important monasteries. Tabo, known as the "Ajanta

of the Himalayas', celebrated it's thousandth birthday last year. Built by the Great Translator Rinchen Tsangpo, Tabo is, from the

exterior, the least imposing of the Himalayan Gompas that I have seen. Tabo doesn't crown some lofty pinnacle, instead it's mud plastered

buildings almost merge into the valley floor. The interiors are a different story altogether. In one dark hall, life size stucco

figurines, mounted some 6 feet off the floor, leer at you out of the gloom. The uncanny effect is enhanced by the perfect

detailing, of these gods and demons of the Tibetan pantheon. Some of the figures are clothed in fine fabrics, now decaying with

the passage of time. Elsewhere are numerous statues of varying sizes, some huge, entire spaces lined with exquisite miniature panels

depicting the thousand Buddhas and many others.

Kenneth Mason in his "Abode of Snow" relates an interesting anecdote. Apparently the world altitude record was held for

nearly 20 years in the late nineteenth century, by an unknown Indian survey assistant who climbed to the top of the 23,000 feet

high Shilla peak in Spiti, in order to plant a survey pole. The heroism of this feat can only be appreciated when one thinks

that he was alone, without any expedition, mountaineering gear, ropes and the like, and yet, he made it where no European

was to go for another twenty years. The modern climber has a choice of a score of unnamed, unclimbed peaks over 6,000 meters to chose from.

Index

Ladakh

Index

Ladakh

|

This page hosted by

Get your own Free Home Page

Get your own Free Home Page

Web Page Design and Images Copyrightę: Karamjeet Singh

The roll call of great peaks continues as the great Himalaya continues it's march

southeastward through Lahaul and Spiti... Menthosa, Lord Gephan, The Gangstang

peaks and glaciers and onto the Chandrabhaga group... gorges,chasms,hanging glaciers

......a landscape for the strong of heart and adventurous of spirit.

The roll call of great peaks continues as the great Himalaya continues it's march

southeastward through Lahaul and Spiti... Menthosa, Lord Gephan, The Gangstang

peaks and glaciers and onto the Chandrabhaga group... gorges,chasms,hanging glaciers

......a landscape for the strong of heart and adventurous of spirit. Crossing over from the Rohtang pass can be a shock ... a sudden transition from the verdant cedar forested slopes of the

Pangi-Pir Panjaal to the bleakness of the Lahaul landscape. A landscape that makes one feel like

Tolkien's Hobbit, adrift in the dark lands of Mordor ... a barren scree covered wilderness surrounded by towering

battlements of rock and ice, up which the twilight shadows creep, black as if painted on. Above them, the

crenellations and spires of the sorceror's castle stand silhouetted against the darkening sky. In the side valleys,

evil looking, snaggle toothed small glaciers hang, poised, and everywhere the howling dervishes that inhabit

the west wind, attempt to tear away your clothes. Batal, at the foot of the Kunzum pass and jump off point for the Bara-Shigri

glacier, is at only 11,000 feet the windiest place I have ever come across in my Himalayan travels. The savagery of the

winters can be gauged from the three bridges at Batal. One in use and the other two, mere ruins. The only other structure

is a PWD rest house with the roof gone and the walls going.

Crossing over from the Rohtang pass can be a shock ... a sudden transition from the verdant cedar forested slopes of the

Pangi-Pir Panjaal to the bleakness of the Lahaul landscape. A landscape that makes one feel like

Tolkien's Hobbit, adrift in the dark lands of Mordor ... a barren scree covered wilderness surrounded by towering

battlements of rock and ice, up which the twilight shadows creep, black as if painted on. Above them, the

crenellations and spires of the sorceror's castle stand silhouetted against the darkening sky. In the side valleys,

evil looking, snaggle toothed small glaciers hang, poised, and everywhere the howling dervishes that inhabit

the west wind, attempt to tear away your clothes. Batal, at the foot of the Kunzum pass and jump off point for the Bara-Shigri

glacier, is at only 11,000 feet the windiest place I have ever come across in my Himalayan travels. The savagery of the

winters can be gauged from the three bridges at Batal. One in use and the other two, mere ruins. The only other structure

is a PWD rest house with the roof gone and the walls going.

Opening out onto the Chandra valley, and adding it's waters to it, is the greater or Bara Shigri glacier, a frozen river of ice

nearly 28 kilometers long and several kilometers wide at it's widest. All around are the great peaks of the Parvati headwaters - White

Sail, Indrasan and further up the range, Kulu Makalu and Parbati peak itself.

Opening out onto the Chandra valley, and adding it's waters to it, is the greater or Bara Shigri glacier, a frozen river of ice

nearly 28 kilometers long and several kilometers wide at it's widest. All around are the great peaks of the Parvati headwaters - White

Sail, Indrasan and further up the range, Kulu Makalu and Parbati peak itself. is one of the famous passes of Himalayan history, for here paths from Zanskar, Ladakh and Lahaul meet, and over the centuries

travellers have crossed in all directions. The two great rivers of Lahaul, the Chandra and the Bhaga also arise from the huge

snowfields on opposite sides of the pass. The Chandra then does a circuitious journey through Lahaul, picking up the waters

of the Samundra Tapu and Bara Shigri glaciers on the way, to finally meet up with the Bhaga at Tandi - forming the celebrated

Chandrabhaga.

is one of the famous passes of Himalayan history, for here paths from Zanskar, Ladakh and Lahaul meet, and over the centuries

travellers have crossed in all directions. The two great rivers of Lahaul, the Chandra and the Bhaga also arise from the huge

snowfields on opposite sides of the pass. The Chandra then does a circuitious journey through Lahaul, picking up the waters

of the Samundra Tapu and Bara Shigri glaciers on the way, to finally meet up with the Bhaga at Tandi - forming the celebrated

Chandrabhaga.

Lahaul is partly Hindu, partly Buddhist and partly, a mixture of both. Nowhere is this better symbolised than at the temple

of Trilokinath near Tandi in western Lahaul, where the idol worshipped as Lord Shiva by the Hindu populace, is venerated as the Buddha

Avilokateshwara by the local Buddhists, as well as pilgrims from Spiti and Ladakh. A few kilometers further up, where the Miyar

Nala meets the Chandrabhaga, lies the temple of Mrikula Devi at Udaipur. A wooden temple built by the Chamba kings in the

6th century A.D, it is ascribed to Gugga - the Michealangelo of the Himalaya. It's interiors are liberally embellished with

exquisite wooden carving that ecelectically display scenes from the Mahabharata and the Ramayana, all interspersed with

scenes from the Buddhist cosmology. The Buddha gives battle to Mara the tempter side by side with Lord Ram as he engages

Ravana. The enshrined goddess, Kali, venerated as Mrikula Devi, is worshipped as Dorje-phag-mo by the Buddhists.

Lahaul is partly Hindu, partly Buddhist and partly, a mixture of both. Nowhere is this better symbolised than at the temple

of Trilokinath near Tandi in western Lahaul, where the idol worshipped as Lord Shiva by the Hindu populace, is venerated as the Buddha

Avilokateshwara by the local Buddhists, as well as pilgrims from Spiti and Ladakh. A few kilometers further up, where the Miyar

Nala meets the Chandrabhaga, lies the temple of Mrikula Devi at Udaipur. A wooden temple built by the Chamba kings in the

6th century A.D, it is ascribed to Gugga - the Michealangelo of the Himalaya. It's interiors are liberally embellished with

exquisite wooden carving that ecelectically display scenes from the Mahabharata and the Ramayana, all interspersed with

scenes from the Buddhist cosmology. The Buddha gives battle to Mara the tempter side by side with Lord Ram as he engages

Ravana. The enshrined goddess, Kali, venerated as Mrikula Devi, is worshipped as Dorje-phag-mo by the Buddhists. Spiti due to it's strategic location was for long closed to tourists except the odd intrepid traveller armed with an 'inner line'

permit. Recently, it has been thrown open for tourism and hitherto insulated cultures are coming into contact with jeep safaris

and video toting tourists. The numbers are still mercifully small though and Spiti offers a fast vanishing look at 'museum'

cultures, especially in the off-route Pin valley.

Spiti due to it's strategic location was for long closed to tourists except the odd intrepid traveller armed with an 'inner line'

permit. Recently, it has been thrown open for tourism and hitherto insulated cultures are coming into contact with jeep safaris

and video toting tourists. The numbers are still mercifully small though and Spiti offers a fast vanishing look at 'museum'

cultures, especially in the off-route Pin valley. The Pin valley is also home to the Buzhen, wandering minstrel lamas who move from village to village enacting

comedies, miracle plays and singing ballads. During the bleak and harsh Spitian winter, they make their colourful way through

the monochromatic landscape entertaining the populations of far flung villages.

The Pin valley is also home to the Buzhen, wandering minstrel lamas who move from village to village enacting

comedies, miracle plays and singing ballads. During the bleak and harsh Spitian winter, they make their colourful way through

the monochromatic landscape entertaining the populations of far flung villages. Spiti is totally Buddhist and is the location of some of Himalayan Buddhism's most important monasteries. Tabo, known as the "Ajanta

of the Himalayas', celebrated it's thousandth birthday last year. Built by the Great Translator Rinchen Tsangpo, Tabo is, from the

exterior, the least imposing of the Himalayan Gompas that I have seen. Tabo doesn't crown some lofty pinnacle, instead it's mud plastered

buildings almost merge into the valley floor. The interiors are a different story altogether. In one dark hall, life size stucco

figurines, mounted some 6 feet off the floor, leer at you out of the gloom. The uncanny effect is enhanced by the perfect

detailing, of these gods and demons of the Tibetan pantheon. Some of the figures are clothed in fine fabrics, now decaying with

the passage of time. Elsewhere are numerous statues of varying sizes, some huge, entire spaces lined with exquisite miniature panels

depicting the thousand Buddhas and many others.

Spiti is totally Buddhist and is the location of some of Himalayan Buddhism's most important monasteries. Tabo, known as the "Ajanta

of the Himalayas', celebrated it's thousandth birthday last year. Built by the Great Translator Rinchen Tsangpo, Tabo is, from the

exterior, the least imposing of the Himalayan Gompas that I have seen. Tabo doesn't crown some lofty pinnacle, instead it's mud plastered

buildings almost merge into the valley floor. The interiors are a different story altogether. In one dark hall, life size stucco

figurines, mounted some 6 feet off the floor, leer at you out of the gloom. The uncanny effect is enhanced by the perfect

detailing, of these gods and demons of the Tibetan pantheon. Some of the figures are clothed in fine fabrics, now decaying with

the passage of time. Elsewhere are numerous statues of varying sizes, some huge, entire spaces lined with exquisite miniature panels

depicting the thousand Buddhas and many others.