THE PAPYRUS OF NES-MIN: AN EGYPTIAN BOOK OF THE DEAD

Detroit Institute of Arts Acc. No. 1988.10.1-24

By William H. Peck

(As published in the Bulletin of the Detroit Institute of Arts 74, no. 1/2 (2000): pp 20–31)

At the end of the fourth century B.C., a Theban priest and scribe named Nesmin, who held numerous positions without ever becoming a member of the upper hierarchy, took with him to the tomb some of his own books instead of the more usual Book of the Dead.

Unknown to the author of the above passage, written in 1997, 1 a Book of the Dead prepared for this priest named Nes-min does indeed exist. It doubtless would have been included in the tomb as a part of the group of documents mentioned. These were not preserved "instead of the more usual Book of the Dead" but probably interred in addition to it. By rare good fortune, the Book of the Dead of Nes-min is in the collection of the Detroit Institute of Arts.2

One of the defining elements of ancient Egyptian culture is the art of picture writing called hieroglyphs. The notion that a civilization developed and maintained a complex written language based on a system of pictures holds a fascination that is undiminished today. Although there were numerous examples of carved hieroglyphic inscriptions in the collection, for many years the DIA lacked an important example of ancient writing on papyrus. A few fragmentary pieces of text of late date, in terms of the history of Egypt, were all the museum had to show for this important medium for the transmission of art, commerce, and religion. Since the collection was also lacking an example of the class termed "figured ostraca" (line drawing on pot shards or limestone chips), there was scant representation of the significant art of drawing from ancient Egypt in any medium. It has amply been demonstrated in the literature on the history of Egyptian art that linear abstraction and the necessary skill in draftsmanship were the underlying principles and the basis for all of the visual arts in Egyptian civilization.

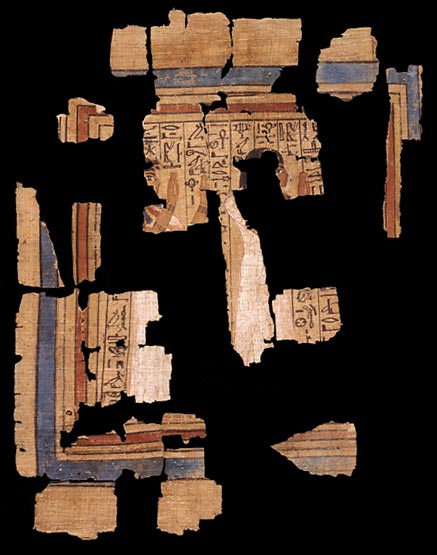

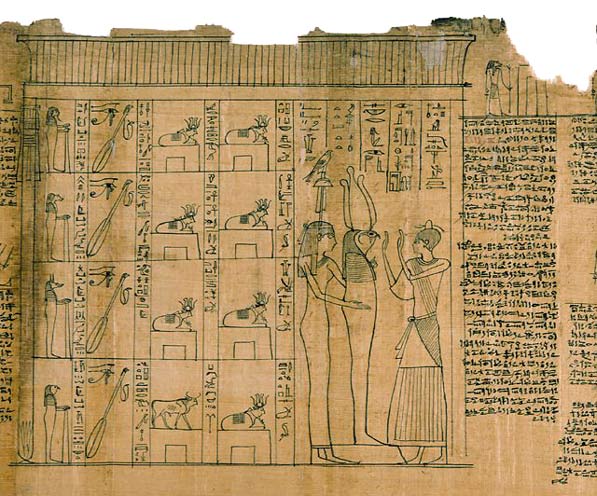

In 1972 Richard A. Parker, a distinguished Egyptologist then on the faculty of Brown University, donated some small fragments of what had once been a remarkable Book of the Dead of the New Kingdom (1550–1070 B.C.), but there was sadly only enough to be able to piece together the sketchy remains of a vignette depicting the deceased, a man named Ptah-hotep, with his wife (fig. 1).

Papyrus of Ptah-hotep. Gift of Dr. Richard A. Parker. Acc. No. 72.49

The preserved portion reveals that the painting had been of excellent quality. The pieces were treated and mounted in the museum's conservation laboratory and placed on exhibition in fragmentary condition. The hope persisted that a better-preserved and typical ink drawing or painted section from a Book of the Dead might be found for the collection, but it was not until 1988 that this was realized in a manner as welcome as it was totally unexpected. The object that was offered to the museum, the Book of the Dead of Nes-min, was a virtually complete example of a papyrus replete with carefully executed drawings of high artistic quality.

To many people today, the Book of the Dead is considered the classic example of an ancient Egyptian religious document. It is a text that is easily accessible to the general public because it has been translated and published in a number of versions, the most popular probably being that of Sir E. A. Wallis Budge, which has been too frequently reprinted 3 despite the fact that it was not a particularly accurate translation and is now more than a century out of date in light of modern scholarship.4 The Book of the Dead has been erroneously considered by enthusiasts of ancient Egyptian civilization to be comparable to the Torah, the Old and New Testaments, or the Qu'ran as an example of revealed religious truth—in short, to have been the "Bible" of the ancient Egyptians. A far better modern comparison would be with the older form of the Anglican Book of Common Prayer, which was also a compilation of texts and prayers and contained spells to ward off evil influences. However, the evolution and development of the Book of the Dead as a religious text must be considered within the history of Egyptian religion.

The earliest developed prayers, hymns, and spells to be preserved are included in the so-called Pyramid Texts of the late Old Kingdom, found carved on the walls of chambers in the burial places of kings of Dynasties 5 and 6 (25th–22th centuries B.C.). Surprisingly, nothing of the kind is preserved in the most famous of all the pyramids from earlier in Dynasty 4 (26th–25th centuries). During a period of decline after Dynasty 4, the kings of Egypt sought to insure their immortality through the addition of engraved prayers and spells to their tomb-pyramids. The Pyramid Texts are a curious collection of religious literature, much of the content of which is presumed by modern scholars to predate the period when it was codified and perhaps even to exemplify the beliefs of the time before and during the unification of the country at the beginning of the third millennium B.C., five to six centuries earlier. These prayers and spells ask for the protection of the spirit of the dead king, that he may be able to confront the adversities and defeat the adversaries he will encounter in the next life and be able to join the gods and be one with them. The daily recitations to be made on behalf of the king's spirit in the temple associated with his pyramid are also included.

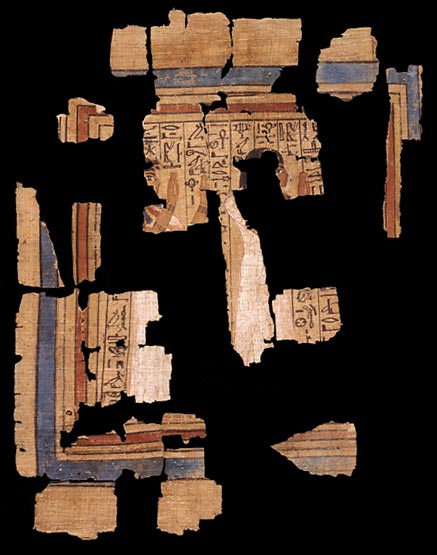

Later, during the Middle Kingdom, particularly Dynasties 9 to 11 (22nd–21st centuries), many of the prayers and spells originally reserved for royalty were somewhat "democratized" and were allowed for the use of members of the nobility. Rather than being carved on the walls of tombs, these texts were written or painted on the inside walls of box-shaped coffins for the deceased, giving these the appearance of small tomb chambers (fig. 2).

Coffon Wall, Founders Society Purchase. Acc. No. 65.394

The original Pyramid Texts of the Old Kingdom were supplemented with other material, often including spells to ward off hunger and thirst as well as specific evils or dangers that the spirit might encounter. These painted compilations of text and spells, for obvious reasons, have been named Coffin Texts. In their number and variety, the texts also add a great deal to our knowledge of the development of Egyptian religious thought, particularly concerning the rising importance of the god Osiris as the protector of the dead.

Beginning during the New Kingdom, as a part of the development of religious beliefs, the new and expanded corpus of texts became available to a larger segment of the population, dependent, however, on what an individual was able to afford. This last major phase in the development of funerary texts is the collection of prayers and spells popularly called the Book of the Dead (the proper title was something along the lines of the book of "going forth [from the tomb] by day"). It was traditionally written on papyrus, although selected passages are found on tomb walls and on some specific funerary objects, as will be discussed below. It was often augmented by a series of illustrations or vignettes mainly related to the various "chapters" (more properly, "spells"). There exist a number of forms or compilations, varying considerably in completeness, that make up the Book of the Dead. They can include as many as 200 spells, which themselves vary considerably in length. It is generally thought that the length and number of spells in any single document depended on the wealth and wishes of the deceased or his/her family or on local religious custom, usage, or tradition. Some examples were produced in the expectation of purchase, with the name and titles of the deceased to be added in designated blank spaces. In various forms, the Book of the Dead was in use in ancient Egypt for almost 1,500 years.

It is a common misconception that the numbering system used in modern publications to designate the spells is ancient. On the contrary, it was devised by Richard Lepsius, the pioneer German Egyptologist, in the early nineteenth century. The names assigned to the various spells are generally derived from the titles or labels used to designate them in the text. These were typically written in red pigment to set them off from the rest of the text, which was written in black ink, an example of the most ancient application of a visual differentiation that has come to be called "rubrics" (deriving from the Latin word for the color red) to designate headings in a religious text.

The religious matter dealt with in the Book of the Dead is the result of a long evolutionary process and is extremely varied. It includes hymns in praise of Re, the sun god, as well as other hymns or prayers addressed to Osiris, the ruler and judge of the spirits of the deceased. There are several sections that deal with the concept of the spirit acquiring the freedom and ability to leave the tomb "by day" or in "triumph over enemies" and in various magical forms or manifestations. Spells are included to allow the spirit to enter and progress through the underworld; to pass all obstacles; to be able to confront the guardians of gates and portals; as well as to breathe, possess a heart and voice, and otherwise function in the next life. They also guard against dangers, as exemplified by serpents and crocodiles.

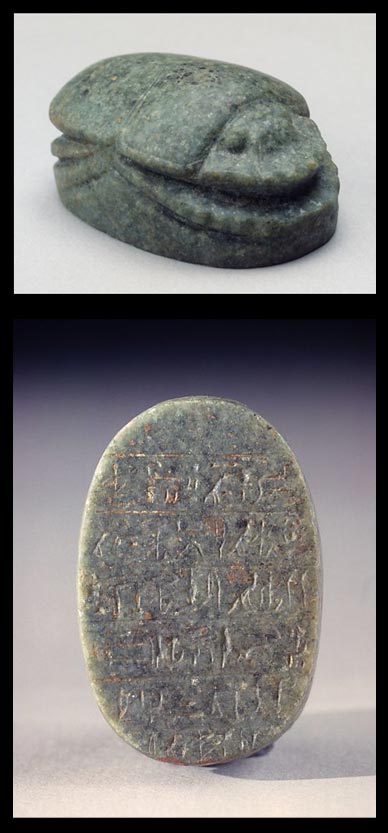

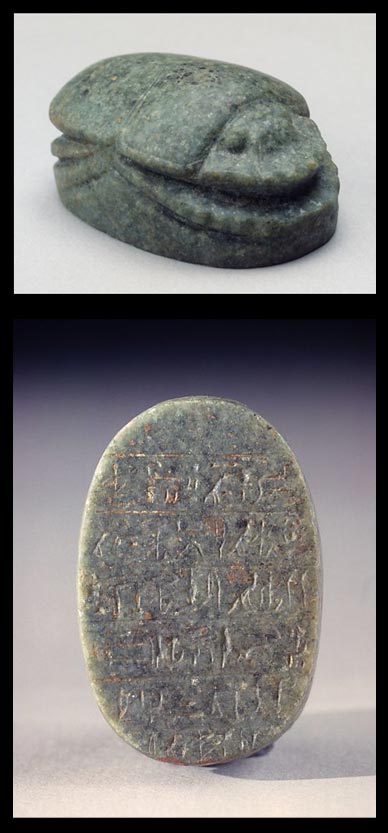

We know the Book of the Dead mainly from examples written on papyrus, the most familiar material, but two of the spells were regularly inscribed on specific funerary objects. One of these is spell 30b, which is found engraved on a special class of amulet called a heart scarab. This was traditionally made of green stone and intended to be wrapped on the mummy over the heart, which, unlike the other internal organs, was left in place in the body (fig. 3).

Heart Scarab. Gift of Ruth C. Loomis. Acc. No. 73.81

The text of the heart scarab addresses the heart of the deceased and pleads that it not rise up and witness against the spirit and influence the weighing of the heart in the balance of judgment. The other frequently found text is spell 6, which is written, impressed, or inscribed on shawabtis, the mummy-form funerary figures intended to magically supply the spirit with workmen (fig. 4).

Shawabti of Hor-wedja. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Earl Jacobs. Acc, No. 81.918

That text asks that the servant figure answer in his or her place if the deceased be required to engage in any work in the next life.

The Book of the Dead of Nes-min was originally a single papyrus in the form of a long scroll measuring thirty-five centimeters (about fourteen inches) high and more than eleven meters long (about thirty-five feet). When it was acquired by the museum, it had been cut into twenty-four sections, generally separated at logical junctures that did not significantly harm the text or the drawings. A previous owner had had three of these sections mounted on Japanese paper and framed. After acquisition by the museum, the papyrus was treated, some of the sections were reunited for the sake of visual clarity and continuity, and each of the parts was remounted and framed in a standard frame size.5

Such rolls of papyrus have sometimes been found broken or otherwise spoiled by mishandling and unrolling without proper care. This does not seem to be the case with the Detroit papyrus. Only one vignette, a scene of four ibis-headed figures at four doors, appears to have been intentionally mutilated, as a complete figure has been removed. Otherwise, the condition of the document is generally good, although the top edge has suffered somewhat and has a ragged appearance. There is discoloration with this tattering, which may have been the result of storage near some material that contaminated the papyrus and caused the damage.

The owner of the Detroit papyrus, as stated above, was a man called Nes-min, whose name means "He belongs to Min"; Min is the primeval god of the city of Coptos and closely associated with Amun. Nes-min had the title of Prophet (priest) of Neferhotep, a somewhat obscure Egyptian deity who was the object of a cult in the region of Hu (known to the Greeks as Diospolis Parva) in Middle Egypt during the late period. He was also a priest of Amun-re at the Temple of Karnak at Thebes, and he counted among his other distinctions the rank of phyle leader, responsible for a contingent (or shift) of priests. Thus his social status would have been such that he could afford a Book of the Dead of good quality and considerable size. It is known from the "colophon" he added to the Bremner-Rhind papyrus (discussed below) in the British Museum, London, that he had more than twenty priestly and other official titles to his credit. These include priesthoods in the service of the gods Amun, Khonsu, Min, Osiris, Isis, Nephtys, Horus, and Hathor, in addition to that of Neferhotep. We know little about the man Nes-min beyond the names of his parents, the titles he held, and the choice of religious texts he took with him to his tomb, but there is one additional and important bit of evidence about him provided by one of those documents.

It was not the usual Egyptian custom to include the year, month, or day in a religious text such as the Book of the Dead, in contrast to personal letters or state, legal, and commercial documents, where a recorded date might have been important. The determination of a period or date for the execution of an example of a religious text is usually based on the linguistic, calligraphic, or artistic style. The identification and dating of a document is further complicated by the fact that ancient Egyptian names were not unique to a single individual and certain names enjoyed definite periods of popularity; "Nes-min" is a name frequently encountered in the Ptolemaic Period (332–30 B.C.), literally to be counted in the hundreds of examples. It is generally only when an individual is not only named but also can be identified with some certainty by titles and family relationships or some genealogical notation that a more exact date can be established for a particular document. Nes-min’s Book of the Dead, however, can be said to be as precisely dated as almost any funerary papyrus in existence. This individual is well known in the Egyptological literature because other papyri belonging to him have been identified and well published in the past.6 In the Detroit papyrus, Nes-min’s father and mother are mentioned by name7 as are some of his somewhat unusual titles, so that we can identify him with great certainty as the owner of two other papyri in the British Museum (BM10208 and BM10209), which give him some of the same titles and the same genealogy. Furthermore, he was the author of the so-called colophon of the Bremner-Rhind papyrus (BM10188). These are the documents, consisting mainly of prayers, mentioned in the quotation at the beginning of this article. The identification of Nes-min with this last papyrus is particularly important because it is dated to year 12 in the reign of Alexander IV, the posthumous son of Alexander the Great, or 306–305 B.C. according to the most recent determinations of Ptolemaic chronology. The logical conclusion is simply that if Nes-min was a mature man alive in 306–305, his Book of the Dead was certainly made during the first half of the third century B.C. and more likely during the first quarter of that century, between 300 and 275.8

Malcolm Mosher, an American scholar who is currently examining various aspects of the Book of the Dead, has included the Detroit papyrus in a study of the forms of late examples from Memphis and Thebes.9 He has read and identified all of the texts in the papyrus, but a complete analytical publication is still to be produced. According to Mosher, the contents of the Detroit papyrus of Nes-min are somewhat typical for a Book of the Dead made late in Egyptian history, at the very beginning of the Ptolemaic Period. He has pointed out that this papyrus contains 148 of the 165 spells that had come to be standard in the Late Period codification of the corpus. He also observed that some of the texts are abbreviated, but that this is not to be considered a fault, because even some indication of a particular spell was deemed to be more effective than omitting it completely.

The text of the document is written in hieratic script, a cursive form of Egyptian hieroglyphic writing, although some of the larger vignettes have texts written in a more formal hieroglyphic hand. In the shape and simplification of individual signs, the cursive script shows the influence and limitations of the reed pen employed to produce it, but it was faster and easier to write and well adapted to a papyrus surface. The relationship of hieratic to the formal hieroglyphic style of writing is roughly comparable to that of modern cursive writing to block printing or printed type. The drawing style of the vignettes is clear, unhesitating, and regular. It is clear that all of the drawings in the papyrus are the work of a single artist. He was a master draftsman with a command of Egyptian standard requirements and proportion and was immensely skilled in the handling of pen and ink, as is shown by the fine and consistent quality of line throughout the whole document. The figures have been slightly abbreviated in a stylized manner for which parallels can be found in other papyri of the same time.

The Book of the Dead of Nes-min is a rich collection of vignettes meant to accompany the various spells of the text. They range in size and complexity from large, multifigured examples to the smallest drawings accompanying short spells. A number of them are exquisite little masterpieces in their own right and show the ability of the artist to capture the look and spirit of human and animal life within the strictures of the rules of Egyptian art. Among these, the drawings of birds should be particularly noted; the standard method of representing the various birds is adhered to but the individuality of types is recognized (see fig. 5).

The tiny drawings at the top edge of the papyrus, which act almost as a continuous frieze, contain many examples of meticulously detailed renderings. These include the ubiquitous images of the deceased, priests and officiants, the gods, and numerous offerings for the good of the spirit of Nes-min.

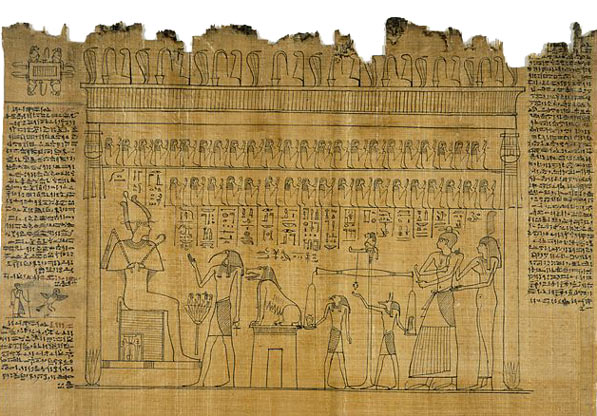

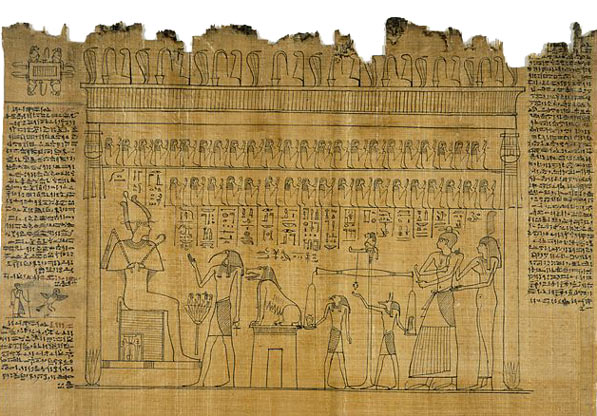

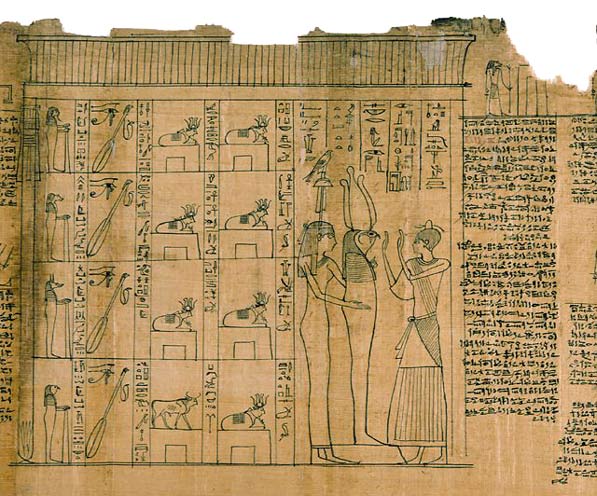

Of all of the vignettes included in any version of the Book of the Dead, probably the most familiar and most often reproduced is the Weighing of the Heart scene representing the individual judgment of the deceased (fig. 6).

Typically, as in the Detroit papyrus, the deceased is led into the Hall of Judgment by the god Thoth, the patron deity of scribes and writing, who is represented as ibis-headed. Nes-min is shown on the far right, accompanied by the goddess Ma'at, the female personification of truth and order, who is identified by the ostrich feather hieroglyph on her head. It is significant that Nes-min not only holds the same feather (twice) in attestation to his adherence to the notion of truthfulness but also wears an amulet of the goddess on a cord around his neck. Before him he is able to witness the weighing of his heart in the scale against the feather of Ma'at. Jackal- and falcon-headed deities assist in the process of weighing, while a baboon, an animal sacred to Thoth, perches at the top of the scale. Ammit, the devouring monster, waits atop a shrine-shaped pedestal to consume the heart if it is found wanting in the balance. Thoth makes a gesture of greeting to Osiris, enthroned as king of the other world. He is accompanied by images of the "Four Sons of Horus," who emerge from a lotus blossom, symbolic of rebirth. The whole action takes place under the attention of forty-one—or forty-two, the standard number, when Osiris is counted—assessors of the dead, each holding, again, the ostrich feather of Ma'at. Above the cavetto, or in-curved, cornice is a decorative frieze of alternating cobras, flaming pots, and ostrich feathers.

This scene is intended to accompany spell 125, traditionally labeled the Negative Confessions but now more properly identified as the Declaration of Innocence, in which the deceased has emphatically rejected "falsehood" and embraced "truth." The spirit is prompted to specifically deny a long list of transgressions of a serious nature, such as theft, murder, sacrilege, blasphemy, and sodomy, but also others that may have been considered trivial or lesser "offenses" such as eavesdropping, babbling, or sullen behavior. The list of transgressions is so detailed and so revealing that it has been compared to the morality espoused in the commandments of the Judeo-Christian tradition or the moral strictures of other religions. In essence, it gives the modern reader a clear idea of what would have been considered a moral and correct way of life in ancient Egypt. It is one of the most vital and often quoted passages in the Book of the Dead. The rubric preceding this lengthy passage tells us that it is to be uttered upon the spirit's arrival at the hall of justice, at the time of the weighing of the heart or the individual judgment.

The drawing style in the Book of the Dead of Nes-min is well exemplified by the execution of this vignette of the Weighing of the Heart. The individual figures appear to be tall and graceful and exhibit an inner coherence of form that tended to gradually weaken during the following Ptolemaic Period, although the treatment of some anatomical parts here prefigures the later style, particularly in some apparently awkward combinations. The linear delineation of figures and parts of figures is done with great care, subtlety, and accuracy and in considerable minute detail. One rather curious peculiarity of the drawing style is the use of an "overlap" in which lines cross or intersect in a manner that almost suggests inadequate prior planning and the consequent necessity for overdrawing. This can be seen particularly in the arms of the figure of Nes-min as they cross his torso and in the detail of the column capitals of the architecture framing the scene of judgment. The overall design and arrangement were carefully thought out; the composition is well balanced, with adequate space allotted to each of the participants in the drama. This distinguishes it from other examples of the Book of the Dead where text and figures vie for space in a crowded format.

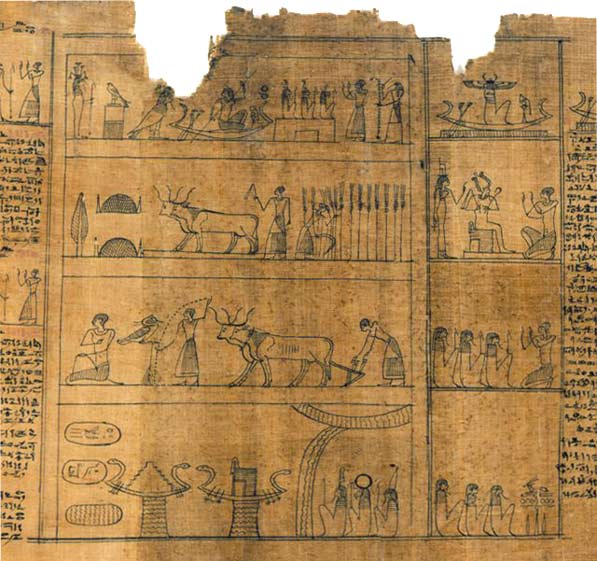

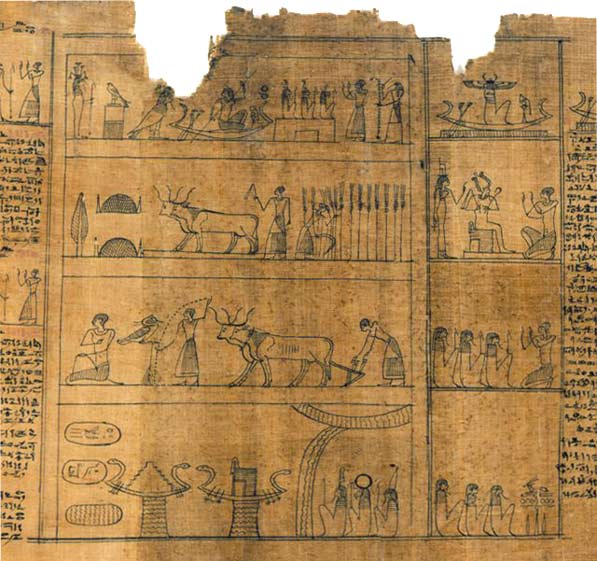

In most Books of the Dead of the Late Period, there are only a select number of vignettes done on a large scale. These include the Weighing of the Heart scene discussed above and a few other formulaic images. A further example of such emphasis in the Detroit papyrus is the composite scene in which Nes-min is depicted carrying out a variety of agricultural activities in the two center registers (fig. 7).

On the right he cuts grain with a curved sickle and on the left drives cattle, which will tread on and thresh it. The piles of grain are shown on the far left. In the next lower register an earlier part of the cycle is depicted in which Nes-min plows the field and sows the grain. The accompanying text reads (in paraphrase), "I plow and I reap in the field of offerings and I am content with the gods." This is a part of the illustration for spell 110, an elaborate homage to the gods that seeks to guarantee the continued good of the spirit of the deceased. The stylized representation of farm activities was standard for this spell in the Book of the Dead and had no direct reference to the occupation of the deceased; nor were these images included to suggest that it would be his fate to labor as a common field hand in the next world. The agricultural cycle of plowing, sowing, reaping, and threshing was seemingly employed as a graphic image of the progression of the seasons, the cycle of beginning and completion, and the continuation of life in which the deceased aspired to participate for eternity.

The variety as well as the quality of illustrations in this Book of the Dead is further exemplified by a vignette with two distinct parts (fig. 8).

On the right is an image of Nes-min adoring two deities. The falcon-headed figure is Sokar-Osiris, a conflation of the qualities of Osiris and Sokar, a falcon-headed god of the necropolis. The goddess next to him is the personification of the West (Imnt), the land of the blessed. Sokar-Osiris is depicted with the typical mummy form and crown associated with images of Osiris. The goddess of the West is identified by the totemic emblem on her head. One of the interesting aspects of the grouping of these three figures is the result of a standard mode of representation found in all two-dimensional art of ancient Egypt. Although the goddess is shown as if she were standing behind the god, she is actually meant to be seen as standing on his right side and thus accompanying him in a position of equality.

The left-hand section of this vignette contains three separate elements that generally appear together and accompany spell 148. These are: the Seven Celestial Cows with the Bull of Heaven, the Four Rudders, and the Four Sons of Horus. The cows and bull are invoked to provide offerings and sustenance for the spirit; the four rudders, or steering oars, symbolize the four cardinal directions or the four corners of the earth; and the four sons of Horus, which were also included in the Weighing of the Heart vignette, are the protectors of the mummified parts, each assigned to a specific canopic jar in which internal organs were preserved. Through each of these somewhat disparate agencies, an appeal for the protection of the spirit is made or implied. All of these elements are enclosed in an architectural framework resembling a shrine.

Although this Book of the Dead was generally executed with care and skill, the artist has inconsistently treated the two ends of this shrine-like structure. Only the left one is delineated as a column. The right side may be unfinished, but it actually looks as if there was a change of design or a lapse of memory from one end of the enclosure to the other, so that the two ends do not match and possibly belong to different types of architectural structures. This was a relatively small mistake, hardly noticeable and hardly affecting the appearance of the composition, but it does underscore the notion that such texts were executed by fallible individuals. Seemingly the product of a careful and meticulous craftsman, the Detroit papyrus is remarkably free of infelicities of design. As such, it can take its place with other important examples of the genre representing one of the last phases in a long tradition of religious literature that has been preserved from ancient Egypt.

When the Detroit papyrus was acquired for the collection of the museum from the New York art market, it had virtually no provenance provided for it other than that it had been known by some Egyptologists to have been in Europe for a number of years. In an effort to determine its recent history, a series of inquiries was made among scholars who have made a particular study of Egyptian papyri of the Late and Ptolemaic Periods, and no satisfactory information was obtained beyond a vague memory on the part of some who recalled it as being in an old German or French collection. The connection provided by the "colophon" of the Bremner-Rhind papyrus may provide a suggestion of its possible modern history, if not solid evidence as to its source.

R. O. Faulkner takes issue with the designation "colophon" for the notation presumably written by Nes-min on the Bremner-Rhind papyrus, since it does not actually date the production of the manuscript or identify the person who wrote it, as a colophon, by definition, is intended to. 10 The date given is the year in which this additional note was made in a handwriting completely different from the original text. This addition is indispensable, however, to the study of the Detroit papyrus. The long list of sacerdotal titles associated with Nes-min and the names of his father and mother in the "colophon" are of utmost importance for the identification of the precise owner of the Detroit papyrus. It is this genealogical evidence, as noted above, by which the Detroit Book of the Dead can be securely connected with the Bremner-Rhind papyrus.11

The Bremner-Rhind papyrus is identified by the names of former owners, as is customary in museum nomenclature. Alexander Henry Rhind was a Scottish lawyer who traveled to Egypt for his health in 1855–56 and 1856–57.12 As did many other educated Europeans who went there for medical reasons, he undertook excavations in the Theban area (modern Luxor). Through excavation or purchase he acquired a large collection of antiquities, which he eventually bequeathed to the National Museum of Antiquities, now the Royal Scottish Museum, in Edinburgh.13 Rhind was very much ahead of his time in that he recognized the importance of recording the context and the finding locations of the objects he excavated. 14 David Bremner was Rhind’s trustee and executor. After Rhind’s death, Bremner sold the papyrus that jointly bears their names, with others, to the British Museum. 15 Why these objects did not go with the rest of Rhind’s collection to Edinburgh is not clear, but the fact that an important papyrus such as the Bremner-Rhind was not included in the bequest suggests that there may have been otherwise unrecognized material in the Rhind collection that was excluded as well. It is thus probable, but impossible to prove, that the Detroit papyrus was a part of the Rhind collection and may have been directed elsewhere, possibly to a private collector. If this is true, it has remained unidentified as such, as the papyrus for the most part has gone unpublished for more than a hundred years. It should be noted, however, that Faulkner said,

Nothing definite is known of the provenance of the [Bremner-Rhind] manuscript, but the presumed last owner, the priest Nesmin who wrote the "Colophon," appears to have been a Theban, judging by the priestly titles he bore. Although there is no direct evidence bearing on the point, it seems probable that the papyrus came from his tomb, and it would be interesting to know in what circumstances a book which appears to have been written originally for a temple library came into the private possession of a member of the priesthood.16

It would be as interesting to know where Rhind acquired the Bremner-Rhind papyrus and the other papyri related to Nes-min, since it is possible that the Detroit papyrus may have come from the same source. In 1964, in pursuit of material for her study of the two other papyri from the Rhind collection, F. M. H. Haikal attempted to collect any other information or material relating to Nes-min in the Luxor area.17 She was successful in finding only a single block from a column inscribed with the name of Nes-min’s father in the northeast section of the Amun precinct of Karnak, near the small temple of Osiris Heqa Djet.

The Egyptians left countless written records in the form of inscription on temple walls and in tombs, which are far more familiar today because they are so often illustrated. In contrast to these monuments, it is to the papyri of ancient Egypt, as to the clay tablets of Mesopotamia, that we must turn to witness the earliest stages of the recording of human thought and memory in a portable form. The acquisition of such an important example of the Book of the Dead for the collection of the Detroit Institute of Arts has added a major and early demonstration of the draftsman’s art but has also provided us with a remarkable specimen of a religious document illustrating the craft of calligraphy and the scroll form as one of the earliest stages in the history of the book.

Notes

The Book of the Dead of Nes-min

Black and red ink on papyrus

Founders Society Purchase, Mr. and Mrs. Allan Shelden III Fund, Ralph Harman Booth Bequest Fund, Hill Memorial Fund

Acc. No. 1988.10.1-24

1

A. Roccati, "Scribes," in The Egyptians, ed. S. Donadoni (Chicago, 1997), 73. Alessandro Roccati has used the material from the tomb of Nes-min as an example of care and concern for important texts to the point that they were included among the furnishings for the spirit of the deceased. The religious texts mentioned are valuable as a collection in representing the attitudes of this time, late in the history of Egypt.

2

The Book of the Dead of Nes-min was created during the Macedonian Dynasty, which began with the conquest of Egypt by Alexander the Great in 332 B.C. and consisted of only three rulers: Alexander III (the Great), his brother Phillip Arrhidaeus, and his son Alexander IV. It was succeeded by the Ptolemaic Dynasty, founded by Ptolemy I Soter, one of the generals of Alexander the Great.

Publications of the Detroit papyrus include:

Leaf 11 (1988.10.11) and leaf 13 (1988.10.13): Masterpieces: Greek, Roman, Egyptian, Ancient Near Eastern (New York, Edward H. Merrin Gallery, exh. cat., 1984), 15.

Leaf 13 (1988.10.13): A. Eggebrecht, Das Alte Ägypten: 3000 Jahre Geschichte und Kultur des Pharaonenreichs (Munich, 1984), 357; "Selected Recent Acquisitions," Bulletin of the Detroit Institute of Arts 64, no. 4 (1989): 55; and D. Meeks and C. Favard-Meeks, Daily Life of the Egyptian Gods (Ithaca, N.Y., 1996), fig. 16.

L. Limme, "Un 'Prince Ramesside' Fantôme," in Aegyptus Museis Rediviva: Miscellanea in Honorem Hermanni de Meulenaere (Brussels, 1993), 114 n. 35, Thebes, doc. 7–10 (where Nes-min is identified as a "prophet of Neferhotep").

M. Mosher Jr., "Theban and Memphite Book of the Dead Traditions in the Late Period," Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt 22 (1992): 143–72; leaf 8 is illustrated as figure 3.

3

E. A. W. Budge, The Book of the Dead (The Papyrus of Ani), 1890, 1894, 1913 (with various additions and emendations).

4

For more up-to-date background material and translations of the Book of the Dead, see

R. O. Faulkner, The Ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead, ed. C. Andrews (New York, 1985); T. G. Allen, The Book of the Dead, or Going Forth by Day, Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization 37 (Chicago, 1974); and idem, The Egyptian Book of the Dead: Documents in the Oriental Institute Museum at the University of Chicago, University of Chicago Oriental Institute Publication 82 (Chicago, 1960).

5

The work on the papyrus was done in the Conservation Services Laboratory of the Detroit Institute of Arts by Valerie Baas and Christopher Foster, conservator and associate conservator of Paper and Photographs. The entire Book of the Dead was displayed as a small adjunct exhibition at the time of the major exhibition "Splendors of Ancient Egypt," July 1997–January 1998.

6

The bibliography on the Bremner-Rhind material includes the following:

E. A. W. Budge, Egyptian Hieratic Papyri in the British Museum (London, 1910).

R. O. Faulkner, The Papyrus Bremner-Rhind (British Museum No. 10188), Bibliotheca Aegyptiaca 3 (Brussels, 1933); "The Bremner-Rhind Papyrus I," Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 22 (1936): 121—40; "The Bremner-Rhind Papyrus II," Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 23 (1937): 10—16; "The Bremner-Rhind Papyrus III," Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 23 (1937): 166—85; "The Bremner-Rhind Papyrus IV," Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 24 (1938): 41—53.

F. M. H. Haikal, Two Hieratic Funerary Papyri of Nesmin, Bibliotheca Aegyptiaca 14 (Brussels, 1970).

W. Spiegelberg, "Das Kolophon des liturgischen Papyrus aus der Zeit des Alexander IV," Recueil de travaux (1913): 35–40.

7

The father: P3 di Imn nb nswt t3 wy. The mother: T3 sri n iht; her other name, Irt ir w, is the one by which she is known in the Detroit Book of the Dead.

8

In a personal communication to the author, Malcolm Mosher suggests 280–270 B.C. based on his study of documents of the period.

9

Mosher 1992 (note 2).

10

Faulkner, "The Bremner-Rhind Papyrus II," 1937 (note 6).

11

The observation that the owner of the Detroit papyrus was the same person as the Nes-min of the three papyri in the British Museum was made at different times by Carol Andrews of the British Museum, Dr. Luc Limme, Musées Royaux d'Art et d'Histoire, Brussels, and Prof. Dr. Herman De Meulenare, Seminarie voor Egyptologie, Rijksuniversiteit-Gent; it was verified by Malcolm Mosher. I offer my thanks to all of these scholars, but particularly to Carol Andrews, who was the first to point out the connection to me.

12

W. R. Dawson and E. P. Uphill, Who Was Who in Egyptology (London, 1972), 247–48

13

Two instances of gifts of large collection of antiquities from Rhind are listed in the Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries, but there is no indication about material going elsewhere. Letter to author from the Department of History and Applied Art, National Museums of Scotland, Edinburgh, May 26, 1999 (DIA curatorial files).

14

Brian M. Fagan laments the fact that Rhind died at the early age of thirty and postulates that he would have been one of the great Egyptologists had he lived (The Rape of the Nile: Tomb Robbers, Tourists, and Archaeologists in Egypt [New York, 1975], 326).

15

The registration entry for February 18, 1865, lists eight papyri (now BM10250, 10057, 10058, 10188, 10208, 10209, 100207, and 16205) as having been "Purchased from David Bremner, Esq., collected by late A H Rhind, Esq." Letter to author from Department of Egyptian Antiquities, British Museum, June 22, 1999 (DIA curatorial files).

16

Faulkner 1936 (note 6).

17

Haikal 1970 (note 6).