/*/ INDEX /*/ NEWS-NOTICIAS /*/ BRADDOCK /*/ IMAGES-FOTOS /*/ REVIEWS-CRÍTICAS /*/

/*/ TECHNICAL DATA-DATOS TÉCNICOS /*/ TRAINING-ENTRENAMIENTO /*/

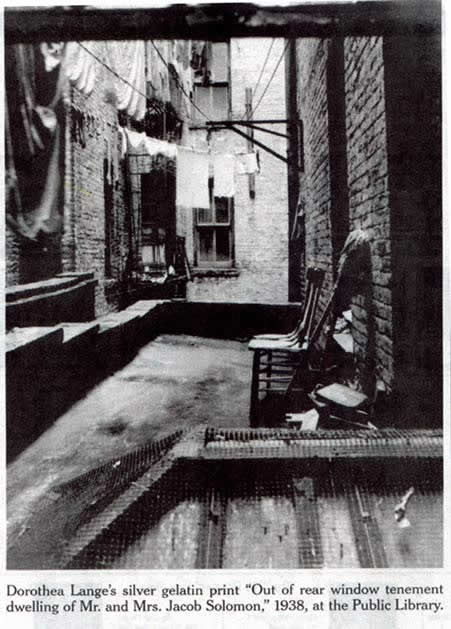

![]()

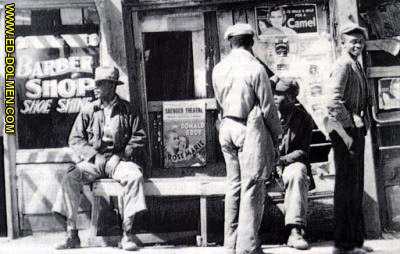

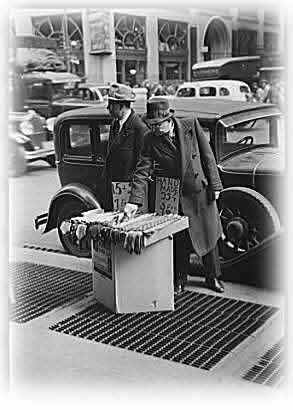

In 1929, Hoover’s first year as president, the prosperity of the 1920s capsized. Stock prices climbed to unprecedented heights, as investors speculated in the stock market. The speculative binge, in which people bought and sold stocks for higher and higher prices, was fueled by easy credit, which allowed purchasers to buy stock “on margin.” If the price of the stock increased, the purchaser made money; if the price fell, the purchaser had to find the money elsewhere to pay off the loan. More and more investors poured money into stocks. Unrestrained buying and selling fed an upward spiral that ended on October 24, 1929, when the stock market collapsed. The great crash shattered the economy. Fortunes vanished in days. Consumers stopped buying, businesses retrenched, banks cut off credit, and a downward spiral began. The Great Depression that began in 1929 would last through the 1930s.

The stock market crash of 1929 did not cause the Great

Depression, but rather signaled its onset. The crash and the depression sprang

from the same cause: the weaknesses of the 1920s economy. An unequal

distribution of income meant that working people and farmers lacked money to buy

durable goods. Crisis prevailed in the agricultural sector, where farmers

produced more than they could sell, and prices fell. Easy credit, meanwhile,

left a debt burden that remained unpayable.

The crisis also crossed the Atlantic. The economies of European nations collapsed because they were weakened by war debts and by trade imbalances; most spent more on importing goods from the United States than they earned by exporting. European nations amassed debts to the United States that they were unable to repay. The prosperity of the 1920s rested on a weak foundation.

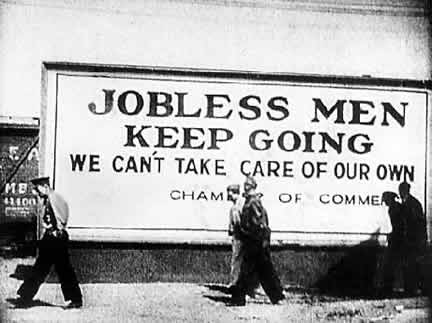

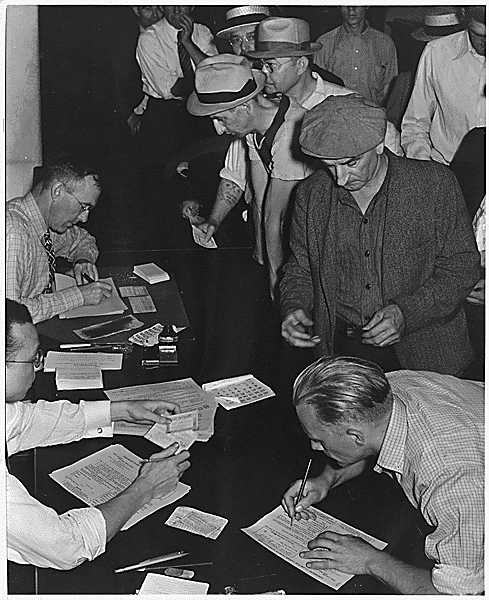

After the crash, the economy raced downhill.

Unemployment, which affected 3 percent of the labor force in 1929, reached 25

percent in 1933. With one out of four Americans out of work, people stopped

spending money. Demand for durable goods—housing, cars, appliances—and

luxuries declined, and production faltered. By 1932 the gross national product

had been cut by almost one-third. By 1933 over 5,000 banks had failed, and more

than 85,000 businesses had gone under.

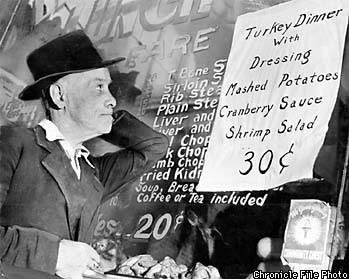

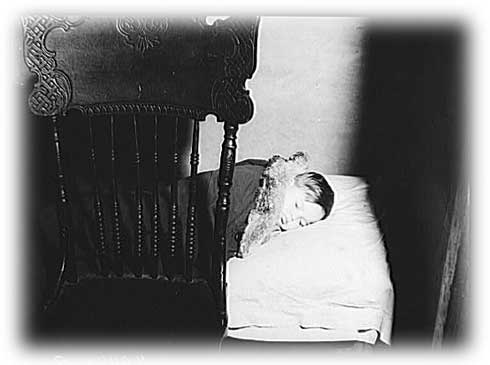

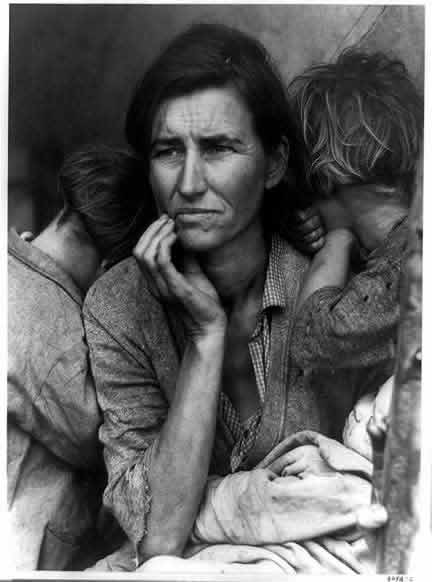

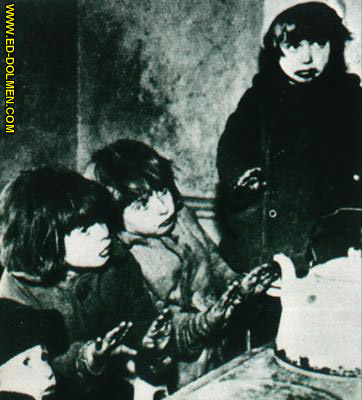

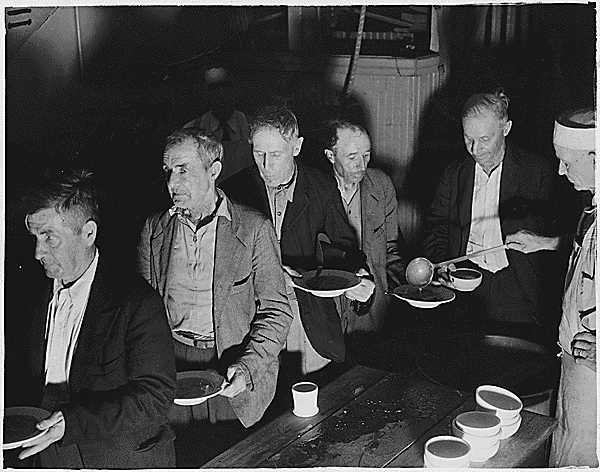

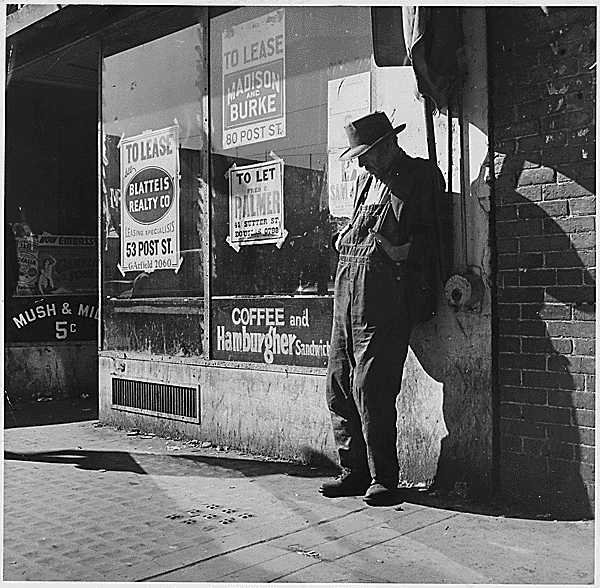

The effects of the Great Depression were devastating. People with jobs had to accept pay cuts, and they were lucky to have work. In cities, the destitute slept in shanties that sprang up in parks or on the outskirts of town, wrapped up in “Hoover blankets” (newspapers) and displaying “Hoover flags” (empty pockets). On the Great Plains, exhausted land combined with drought to ravage farms, destroy crops, and turn agricultural families into migrant workers. An area encompassing parts of Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, New Mexico, and Colorado became known as the Dust Bowl. Family life changed drastically. Marriage and birth rates fell, and divorce rates rose. Unemployed breadwinners grew depressed; housewives struggled to make ends meet; young adults relinquished career plans and took whatever work they could get.

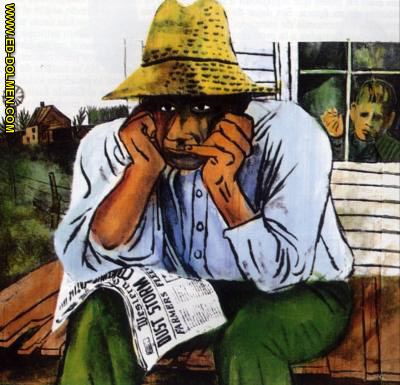

Modest local welfare resources and charities barely

made a dent in the misery. In African American communities, unemployment was

disproportionately severe. In Chicago in 1931, 43.5 percent of black men and

58.5 percent of black women were out of work, compared with 29.7 percent of

white men and 19.1 percent of white women. As jobs vanished in the Southwest,

the federal government urged Mexican Americans to return to Mexico; some 300,000

left or were deported.

On some occasions, the depression called up a spirit of

unity and cooperation. Families shared their resources with relatives, and

voluntary agencies offered what aid they could. Invariably, the experience of

living through the depression changed attitudes for life. “There was one major

goal in my life,” one woman recalled, “and that was never to be poor again.”

President Hoover, known as a progressive and

humanitarian, responded to the calamity with modest remedies. At first, he

proposed voluntary agreements by businesses to maintain production and

employment; he also started small public works programs. Hoover feared that if

the government handed out welfare to people in need, it would weaken the moral

fiber of America.

Hoover finally sponsored a measure to help businesses

in the hope that benefits would “trickle down” to others. With his support,

Congress created the Reconstruction

Finance Corporation in 1932 that gave generous loans to banks, insurance companies, and

railroads. But the downward spiral of price decline and job loss continued.

Hoover’s measures were too few, too limited, and too late.

Hoover’s reputation suffered further when war veterans marched on Washington to demand that Congress pay the bonuses it owed them. When legislators refused, much of the Bonus Army dispersed, but a segment camped out near the Capitol and refused to leave. Hoover ordered the army under General Douglas MacArthur to evict the marchers and burn their settlement. This harsh response to veterans injured Hoover in the landmark election of 1932, where he faced Democrat Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Roosevelt was New York’s governor and a consummate politician. He defeated Hoover, winning 57 percent of the popular vote; the Democrats also took control of both houses of Congress. Voters gave Roosevelt a mandate for action.

Roosevelt was a progressive who had been a supporter of

Woodrow Wilson. He believed in active government and experimentation. His

approach to the Great Depression changed the role of the U.S. government by

increasing its power in unprecedented ways.

Roosevelt gathered a “brain trust”—professors, lawyers, business leaders, and social welfare proponents—to advise him, especially on economic issues. He was also influenced by his cabinet, which included Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes, Secretary of State Cordell Hull, Secretary of Agriculture Henry Wallace, and Labor Secretary Frances Perkins, the first woman cabinet member. A final influence on Roosevelt was his wife, Eleanor, whose activist philosophy had been shaped by the women’s movement. With Eleanor Roosevelt in the White House, the disadvantaged gained an advocate. Federal officials sought her attention, pressure groups pursued her, journalists followed her, and constituents admired her.

Unlike Hoover, Roosevelt took strong steps immediately

to battle the depression and stimulate the U.S. economy. When he assumed office

in 1933, a banking crisis was in progress. More than 5,000 banks had failed, and

many governors had curtailed banking operations. Roosevelt closed the banks, and

Congress passed an Emergency Banking Act, which saved banks in sounder financial

shape. After the “bank holiday,” people gradually regained confidence in

banks. The United States also abandoned the gold standard and put more money

into circulation.

Next, in what was known as the First Hundred Days,

Roosevelt and the Democratic Congress enacted a slew of measures to combat the

depression and prevent its recurrence. The measures of 1933 included: the

Agricultural Adjustment Act, which paid farmers to curtail their production (later

upset by the Supreme Court); the National

Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA), which established codes of fair competition to regulate

industry and guaranteed labor’s right to collective bargaining (again, the law

was overturned in 1935); and the Public

Works Administration, which constructed roads, dams, and public buildings. Other acts of the

First Hundred Days created the Federal

Deposit Insurance Corporation, which insured deposits in

banks in case banks failed, and the Tennessee

Valley Authority (TVA), which provided electric power to areas of the southeast. The

government also set up work camps for the unemployed, refinanced mortgages,

provided emergency relief, and regulated the stock market through the Securities

and Exchange Commission.

The emergency measures raised employment, but the New

Deal

evoked angry criticism. On the right, conservative business

leaders and politicians assailed New Deal programs. In popular radio sermons,

Father Charles Coughlin, once a supporter of Roosevelt, denounced the

administration’s policies and revealed nativist, anti-Semitic views. The

Supreme Court, appointed mainly by Republicans, was another staunch foe; it

struck down many pieces of New Deal legislation, such as the NIRA, farm mortgage

relief, and the minimum wage.

On the left, critics believed that Roosevelt had not done enough and endorsed stronger measures. In California, senior citizens rallied behind the Townsend Plan, which urged that everyone over the age of 65 receive $200 a month from the government, provided that each recipient spend the entire amount to boost the economy. The plan’s popularity mobilized support for old-age pensions. In Louisiana, Democratic governor Huey Long campaigned for “soak the rich” tax schemes that would outlaw large incomes and inheritances, and for social programs that would “Share Our Wealth” among all people. The growing Communist Party, finally, urged people to repudiate capitalism and to allow the government to take over the means of production.

In 1935 the New Deal veered left with further efforts

to promote social welfare and exert federal control over business enterprise.

The Securities and Exchange Commission Act of 1934 enforced honesty in issuing

corporate securities. The Wagner Act of 1935 recognized employees’ bargaining

rights and established a National Labor Relations Board to oversee relations

between employers and employees. Finally, the Work Projects Administration put

unemployed people to work on short-term public projects.

New Dealers also enacted a series of measures to

regulate utilities, to increase taxes on corporations and citizens with high

incomes, and to empower the Federal Reserve Board to regulate the economy.

Finally, the administration proposed the Social Security Act of 1935, which

established a system of unemployment insurance, old-age pensions, and federal

grants to the states to aid the aged, the handicapped, and families with

dependent children. Largely an insurance program, Social

Security was

the keystone of welfare policy for decades to come.

In the election of 1936, Roosevelt defeated his

Republican opponent, Alf Landon, in a landslide and carried every state but

Maine and Vermont. The election confirmed that many Americans accepted and

supported the New Deal. It also showed that the constituency of the Democratic

Party had changed. The vast Democratic majority reflected an amalgam of groups

called the New Deal coalition, which included organized labor, farmers, new

immigrants, city dwellers, African Americans (who switched their allegiance from

the party of Lincoln), and, finally, white Southern Democrats.

At the start of Roosevelt’s second term in 1937, some

progress had been made against the depression; the gross output of goods and

services reached their 1929 level. But there were difficulties in store for the

New Deal. Republicans resented the administration’s efforts to control the

economy. Unemployment was still high, and per capita income was less than in

1929. The economy plunged again in the so-called Roosevelt recession of 1937,

caused by reduced government spending and the new social security taxes. To

battle the recession and to stimulate the economy, Roosevelt initiated a

spending program. In 1938 New Dealers passed a Second Agricultural Adjustment

Act to replace the first one that the Supreme Court had overturned and the

Wagner Housing Act, which funded construction of low-cost housing.

Meanwhile, the president battled the Supreme Court,

which had upset several New Deal measures and was ready to dismantle more.

Roosevelt attacked indirectly; he asked Congress for power to appoint an

additional justice for each sitting justice over the age of 70. The proposal

threatened the Court’s conservative majority. In a blow to Roosevelt, Congress

rejected the so-called court-packing bill. But the Supreme Court changed its

stance and began to approve some New Deal measures, such as the minimum wage in

1937.

During Roosevelt’s second term, the labor movement

made gains. Industrial unionism (unions that welcomed all the workers in an

industry) now challenged the older brand of craft unionism (skilled workers in a

particular trade), represented by the American Federation of Labor (AFL). In

1936 John

L. Lewis, head of the United

Mine Workers of America (UMWA), left the AFL to organize a labor federation based on industrial

unionism. He founded the Committee for Industrial Organizations, later known as

the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO). Industrial unionism spurred a

major sit-down strike in the auto industry in 1937. Next, violence erupted at a

steelworkers’ strike in Chicago, where police killed ten strikers. The auto

and steel industries, however, agreed to bargain collectively with workers, and

these labor victories led to a surge in union membership.

Finally, in 1938 Congress passed another landmark law,

the Fair

Labor Standards Act (FLSA). It established federal standards for maximum hours and minimum

wages for workers in industries involved in interstate commerce. At first the

law affected only a minority of workers, but gradually Congress extended it so

that by 1970 it covered most employees. In the 1930s, however, many New Deal

measures, such as labor laws, had a limited impact. African Americans, for

instance, failed to benefit from FLSA because they were engaged mainly in

nonindustrial jobs, such as agricultural or domestic work, which were not

covered by the law. New Deal relief programs also sometimes discriminated by

race.

The New Deal never ended the Great Depression, which

continued until the United States’ entry into World War II revived the

economy. As late as 1940, 15 percent of the labor force was unemployed. Nor did

the New Deal redistribute wealth or challenge capitalism. But in the short run,

the New Deal averted disaster and alleviated misery, and its long-term effects

were profound.

One long-term effect was an activist state that

extended the powers of government in unprecedented ways, particularly in the

economy. The state now moderated wild swings of the business cycle, stood

between the citizen and sudden destitution, and recognized a level of

subsistence beneath which citizens should not fall.

The New Deal also realigned political loyalties. A

major legacy was the Democratic coalition, the diverse groups of voters,

including African Americans, union members, farmers, and immigrants, who backed

Roosevelt and continued to vote Democratic.

The New Deal’s most important legacy was a new

political philosophy, liberalism, to which many Americans remained attached for decades to come. By the

end of the 1930s, World War II had broken out in Europe, and the country began

to shift its focus from domestic reform to foreign policy and defense.

Microsoft® Encarta® Online Encyclopedia

2003

http://encarta.msn.com © 1997-2003 Microsoft Corporation. All Rights Reserved.

LA GRAN DEPRESIÓN ECONÓMICA EN LOS ESTADOS UNIDOS

El

primer año del mandato del presidente Herbert Clark Hoover se vio marcado por

un suceso que hizo tambalearse los cimientos económicos del país: el

hundimiento del mercado de valores ocurrido en 1929. Durante el periodo de

expansión económica en esa misma década, muchos ciudadanos y empresas

invirtieron sus ahorros y beneficios en sectores especulativos.

Los

precios de las acciones alcanzaron su mayor nivel durante los primeros seis

meses del mandato de Hoover. En este periodo, los particulares invirtieron miles

de millones de dólares en el mercado bursátil, obteniendo el dinero para tales

inversiones gracias a préstamos bancarios, la hipoteca de sus casas y la venta

de obligaciones del Estado. En octubre de 1929 la fiebre compradora se había

agotado y dio paso a otra fiebre, en este caso vendedora. Los precios se

hundieron y miles de personas perdieron todo lo que habían invertido, lo que

supuso, en muchos casos, su completa ruina financiera. El 29 de octubre, el

mercado de valores de Nueva York conoció su peor día y se produjo una situación

de pánico. A finales de ese año, la caída de los valores de las acciones había

alcanzado la cifra de 15.000 millones de dólares.

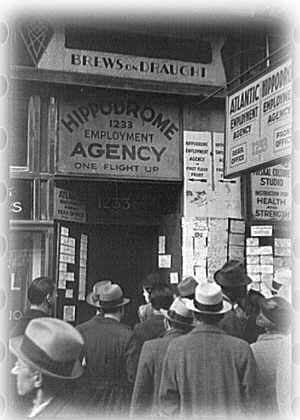

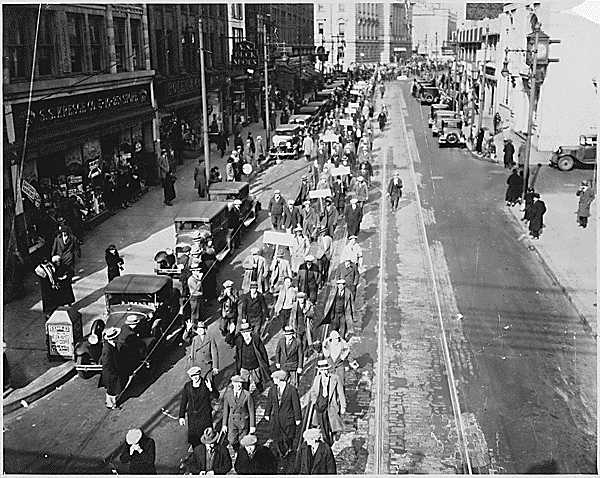

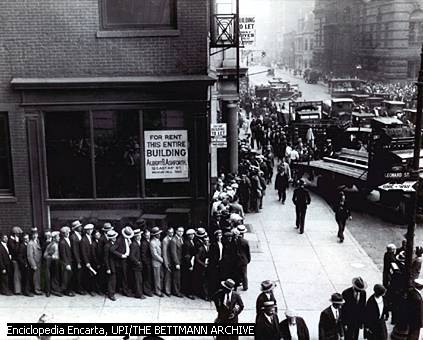

Cola de desempleados durante la Gran Depresión

El

hundimiento de la Bolsa neoyorquina de Wall Street en 1929 provocó la Gran

Depresión, la peor crisis económica mundial de la historia, que se prolongó a

lo largo de casi una década y en la cual cientos de miles de estadounidenses

perdieron sus empleos, los negocios se hundieron y las instituciones financieras

quebraron.

Microsoft ® Encarta ® Biblioteca de Consulta 2003. © 1993-2002

Microsoft Corporation. Reservados todos los derechos.

El

hundimiento de la Bolsa precedió a una depresión económica que no sólo

afectó a Estados Unidos, sino que a comienzos de la década de 1930 adquirió

dimensiones mundiales. Se cerraron fábricas, el paro se incrementó de forma

constante, los bancos se hundieron y la inflación subió de forma incesante.

Entre las medidas adoptadas se incluyeron la realización de obras públicas, la

modificación de las normas del sistema de la Reserva Federal para facilitar que

los hombres de negocios y los granjeros obtuvieran créditos, y la creación de

la Corporación Financiera para la Reconstrucción con la finalidad de conceder

préstamos de urgencia a las industrias, a las compañías ferroviarias, a las

compañías de seguro y a los bancos. No obstante, la depresión económica

empeoró aún más, de tal modo que en 1932 cientos de bancos habían quebrado,

cientos de empresas y de fábricas habían cerrado y más de diez millones de

trabajadores estaban sin empleo. La campaña presidencial de 1932 estuvo marcada

por la crisis económica. Los demócratas, liderados por Franklin Delano

Roosevelt, obtuvieron una victoria abrumadora.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt

Cortesía

de Gordon Skene Sound Collection. Reservados

todos los derechos./National Portrait Gallery/Art Resource, NY

A pesar de sufrir

la polio en 1921 a los 39 años, Franklin Delano Roosevelt estaba determinado a

llevar una activa vida política. En 1932, ganó cómodamente la presidencia.

Debido a la Gran Depresión, instituyó el New Deal, que incluía una

serie de medidas destinadas a la recuperación económica. El New Deal

revolucionó la forma de vida estadounidense desde el punto de vista político,

económico y social. La mayor parte de la nación apoyó su política y

Roosevelt fue reelegido tres veces más de forma consecutiva.

Microsoft ® Encarta ® Biblioteca de Consulta 2003. © 1993-2002

Microsoft Corporation. Reservados todos los derechos.

La

política económica y social de Roosevelt fue conocida como New Deal. Tenía un

doble objetivo: la recuperación de la depresión económica que había surgido

tras la crisis financiera de 1929 y la estabilización de la economía nacional

para evitar otras severas crisis en el futuro.

Culver Pictures

El ‘erial polvoriento’

Durante la década

de 1930, la región del sur de las Grandes Llanuras de Estados Unidos, llamada

el 'erial polvoriento', sufrió una severa erosión de aire tras varios años de

sequía y sobreexplotación. La política del New Deal del presidente

Franklin Roosevelt ayudó a aliviar las pérdidas económicas y se introdujeron

nuevos métodos de conservación de la tierra.

Microsoft

® Encarta ® Biblioteca de Consulta 2003. © 1993-2002 Microsoft Corporation.

Reservados todos los derechos.

El

gobierno creó diversos organismos para socorrer a los desempleados y a los más

necesitados. Se distribuyeron subsidios de desempleo mediante agencias locales,

estatales y federales que crearon trabajos temporales, se ayudó a los

granjeros, industriales y obreros, se modernizaron las condiciones de vida

rurales mediante la incorporación de maquinaria agrícola, se crearon diversos

organismos para fomentar la construcción de viviendas. Con la aprobación de la

Ley de la Seguridad Social Estados Unidos dio un gran paso adelante para

garantizar la seguridad económica a su población. Esta ley otorgaba ingresos a

la tercera edad, una compensación a los desempleados y servicios de bienestar

social a madres, niños, mayores y ciegos.

Los

primeros que sufrieron la crisis de 1929 fueron los inversores y los clientes de

los bancos. El New Deal también tuvo en cuenta los intereses de estos grupos.

La Ley de Obligaciones Federales (1933) protegía a los inversores contra

practicas fraudulentas. Para proteger a los impositores bancarios, el Congreso

aprobó la Ley de Emergencia Bancaria (1933) que otorgaba al presidente la

facultad de reorganizar los bancos insolventes. La política para luchar contra

la inflación se centró en la devaluación del dólar.

También

los grandes negocios salieron beneficiados: se otorgaron créditos a compañías

ferroviarias, a bancos, a corporaciones de crédito agrícola, a compañías de

seguros y a instituciones crediticias para vivienda. Con el fin de recaudar los

fondos necesarios para financiar la política del New Deal, el Gobierno

incrementó ligeramente los impuestos sobre bienes, ingresos, beneficios de

corporaciones y emitió deuda pública.

El

New Deal fue alabado por los que creían que había salvado al país de la

adopción de soluciones revolucionarias, ya fueran fascistas o socialistas,

aunque fue muy criticado por otros que vieron en la política de Roosevelt un

peligroso recorte de los derechos asegurados por el sistema de libre mercado. En

las elecciones de 1936, Roosevelt obtuvo una de las mayores victorias políticas

de la historia estadounidense.

Su

segundo mandato estuvo marcado por la polémica en relación con el Tribunal

Supremo que había declarado inconstitucional, en parte o en su totalidad, gran

número de las medidas gubernamentales, como la Ley de Recuperación de la

Industria Nacional (1933). La pretensión de Roosevelt de disminuir el número

de miembros del Tribunal Supremo fue rechazada por el Senado; sin embargo, el

fallecimiento de varios de ellos permitió su sustitución por otros favorables

al New Deal.

Biblioteca

de Consulta Microsoft® Encarta® 2003. © 1993-2002 Microsoft Corporation.

Reservados todos los derechos.

|

OTHER WEB SITES INFORMATION * Life During The Great Depression 1 (Murphsplace) *

Life

During The Great Depression 2

|

*Gran Depresión. Crack de Wall Street. Bolsa de Nueva York. New Deal (html.rincondelvago.com) *Las causas de la Gran Depresión de la década del '30 y lecciones para hoy (www.herramienta.com) *Principales causas de la gran depresión (ateneo virtual.org) *La crisis de 1929 (Artehistoria) *Hoovervilles o ciudades de lata (www.yotor.net)

|

![]() Galería de fotos - Photo gallery

Galería de fotos - Photo gallery

|

Disclaimer, none of the pictures of this site are the property of the author. The copyrights belong to various photographers, publications, and or movie production companies. These pictures are displayed for education and enjoyment only, I gain no profit from their use. I have no products for sale, no affiliation with any advertising companies, and no monetary support from any entity. This is only a fan site. |

Niego que alguna de las imágenes de este sitio, sean de mi propiedad . Los derechos de autor pertenecen a varios fotógrafos, publicaciones y a compañías productoras cinematográficas. Estas imágenes están exhibidas sólo para educación y entretenimiento, y no obtengo ninguna ganancia de su uso. No tengo productos a la venta, ni asociación con ninguna compañía de publicidad y no recibo ayuda monetaria de ninguna entidad. Este es sólo un sitio construido por una fan. |