Semi-Comprehensive Argument Against Belief in Deities

by Patrick Mooney

1997-2003

{Incomplete and Abandoned}

Initial Considerations

This essay was never completed, and has largely been abandoned. It grew out of a final essay for Philosophy 101 at the end of 1997. (Question: "Argue for or against the existence of a god.") Quite frankly, I'm not that fond of the essay, and I hadn't planned on posting it after the conversion of the site fo MoonBase 3.0. But I received several e-mails requesting that the essay be put back up, so ... it's back up. Yes, I'm aware that the writing is bombastic, overly circuitous, repetitive, etc., and I'd llike to think that I'm a much better writer now. I'm not willing to go back and re-write the whole thing at this point, so I'm simply posting it here as a resource for those who want it. If it doesn't meet your needs, check the library at the Secular Web, which has better essays on this topic.

Many of the examples in this essay refer specifically to Christianity, although I intend for this essay to be a general argument against belief in any god. There are several very good reasons for this:

- Western culture has a strongly Christian foundation, and many citizens of any Western country are Christian to this day. Using Christian examples makes the argument easily understandible to most readers.

- One of the reasons that I initially decided to post this essay on my site, even though it wasn't finished, is that I wound up handing out several copies of it to people who preached at me. In fact, this was one of the reasons that I began writing the essay in the first place. Now, I can simply tell people to refer to it here. Ninety-eight and a half percent of the time, people who preach at me are Christians. Members of other, more mature religions (such as Wiccans, Buddhists, and so on) are, quite simply speaking, not nearly so offensive and obnoxious in their proselytizing habits as many Christians are.

- Christianity is one of the least mature religions, and is one of the least respectful of other people's beliefs. So, I pick on it.

It's true that you can argue that the above statement (about Christianity not respecting other religions and about irritating Christian proselytization) doesn't apply to your version of Christianity, especially if you belong to one of the more liberal Christian sects, but then all you're really doing is ignoring biblical passages such as Matthew 28:19, which tell you to go out and preach, god dammit, whether or not the people to whom you're preaching already have a religion or way of looking at the world, and whether or not they want to hear about a puzzling, nihilistic Jew who died on a cross two thousand years ago.

I don't hand out copies of this essay any more. I hand out copies of The Heirophant's Proselytizer Questionnaire instead. I encourage you to do the same.

- I'm more familiar with Christianity than with other religions.

I don't think it's worth my time to continue to work on this essay, and I'm not really interested in receiving feedback about it. If you really need to argue with a heathen, please find someone else to argue with. If you absolutely have to yell at me, please yell at me about The Heirophant's Proselytizer Questionnaire instead.

Table of Contents

Introduction

On finding myself in the world, I look around in wonder at all of the things that are. The simple fact that they exist causes me to express my amazement, and to want to find out what they are, if they were made, and what they are for, if they are for anything at all. I find myself equipped with many tools for the living of my life: the five senses, sight, touch, smell, hearing, and taste; the ability to use all of these senses and to understand the information they give to me; and the ability to think, to take the data given to me by my senses and to understand it, to not only see what this information tells me on its own, but what it can tell me when I put all of it together.

For thousands upon thousands of years, people have wondered at the mysteries that life presented, and over these thousands of years, many people have tried to explain the mysteries around them with a huge multitude of different theories. Some have turned to spiritual explanations, requiring a belief in a deity, or more than one deity, to explain the world around them. Sometimes these deities have been pictured as anthropomorphic, meaning they looked more or less like human beings, and sometimes they looked more like other animals. Other people pictured their deities as forces of nature, as nature itself, or as a sum totality of all life; these gods did not resemble human beings at all. And some people have not had any experience of supreme beings, but turn to other methods to explain what they find around them.

It seems, then, that my task is to find for myself an answer to these mysteries of life, if I can and if I dare. Dare I? Should I? Do I even want to? And if so, why?

I examine the alternatives, of which I can see three. The first is to ignore these issues. If I do that, I go through life with nothing to guide me as to what kind of life I should live, what my life means, and what the things that happen to me mean. If I ignore these issues, than I die in ignorance as to any grand design or purpose my life may have. If there was meaning along the way, I missed it. If there was a way to interpret my life and make sense of it, I failed to find that. If there was a certain way that my life should have been lived, for any reason, then I probably failed to do that. But the most horrible thing about dying without even trying to solve these ancient mysteries for myself is that I am missing a chance to enrich the quality of my own life. If I discover that my life means something, and I know what my life means, then I can guide my life so that it has a greater meaning. If there is a set of rules by which I should live my life, for whatever reason, then I can discover those and satisfy myself that I have lived up to the standards that I should follow, for whatever reason I should follow them. In short, if I fail to discover what my life means, how I should live it, and what my life is for, then I run the great risk of living a life of the lowest possible quality.

The second alternative I can envision is to simply believe whatever the people around me tell me about these ancient mysteries. But if I do this, then I run the risk that the people around me are wrong about the answers to these questions. Certainly, it may seem that the people around me, especially the people who raised me, are most likely to have the answers, but that may just be because the people around me have provided answers to me all my life, and I'm used to getting answers from them and people who more or less agree with them -- essentially, people in my culture. (Philosophers and social scientists call this position cultural relativism.) But just because these people give my answers doesn't necessarily mean that these answers are right. I need to find a way to independently verify these answers on my own. And, if I accept the answers that the people around me want me to accept without even questioning whether those answers are correct, I run the risk of making the same mistakes as I did if I chose the first option -- but this time I would intentionally be embracing a viewpoint just because it was the easiest way. Because I would want to go out of my way enough to embrace a particular viewpoint, but not enough to decide which one to choose, then (if I were wrong) my life would be not only tragic, but ironic -- because I intentionally set out to choose a method of living and discovering meaning in my life, but wandered off the path when it became difficult.

And the third alternative is, of course, to try to discover what these answers to these ancient mysteries are on my own.

<Expand?>

<Establish the necessity of using reason. Argue that, despite the fact that reason has its limitations, it provides for an attempt at objectivity. Preliminary introduction to arguments based on wishful thinking and "the obvious. " is a word referring to a specific philosophical school of thought, which descends from Ren?Descartes; rationalism, with a lower case "r," simply means "of or pertaining to rationality or reason." For the sake of consistency, I will continue to refer to "Empiricism" with a capital "E," although there is no comparable word, at least according to my knowledge and my dictionary, such that the use of a lower-case "e" would cause confusion.

Both of these viewpoints, by themselves, seem to me to be inadequate. The Rationalist viewpoint is problematic because there is nothing to base reasoning on without sensory experience. The Empiricist viewpoint is lacking because it only allows us to stockpile a large number of facts without using our reason to organize or interpret them in a meaningful way with any degree of certainty. Thus, I think that both Descartes and Hume make good points, but that their viewpoints need to be integrated to provide a meaningful life-view of epistemology. It is completely possible that there is a "malicious deceiver" who influences our sensory experience solely for the purpose of tricking us -- at least, there is certainly no proof that of the nonexistence of a "malicious deceiver." And just as clearly, any interpretation of natural law could be mistaken. However, my purpose in philosophical reasoning is to provide a method for living, or set of ethics, and a meaningful way of interpreting my life; in essence, I need to formulate a viable philosophy. And so, because I cannot spend my life sitting paralyzed in my room, it is necessary to ask myself what I can know, what I do know, and what that means for my life. Even if a malicious deceiver does exist, there is no way for us to know this; we have to live within the world which the malicious deceiver forces us to perceive. And so, even if we are living in a world which is created for use by some evil, supernatural force, we need to find a way to live within that world, so that we can know how we should live within it, what our life within this world means, and how this life can be understood. That is the meaning and purpose of philosophy.

Furthermore, it seems to me that there are neither purely Rationalist nor purely Empirical arguments in actual existence. All Empirical arguments must, of necessity, use logic, or else they would not be arguments at all, but rather a massive collection of facts from which we are forbidden to draw conclusions meaningfully. Additionally, all Rationalist arguments must be based on sensory experience, or there would be no data to draw conclusions from. Even Descartes' famous "cogito, ergo sum" (I think, therefore I am) is no exception to this rule, because the cogito (the "I think") is based upon the idea of a self. As Merleau-Ponty pointed out, a child cannot develop a concept of self in a vacuum, but only in relation to by differentiating that "self" from others. Therefore, it is not meaningful to speak of purely Empiricist or purely Rationalist arguments, but only to speak of primarily Empiricist or primarily Rationalist arguments. For the purposes of this argument, I will define an argument as primarily Rationalistic if the point of the argument is primarily made through logic or other forms of cognition; a primarily Empirical argument will be defined as an argument when its point is primarily made by pointing to Empirical evidence and continues by either inviting the reader/listener to draw his or her own conclusions, or leads the reader/listener to a certain conclusion. For the remainder of this essay, I will refer to arguments as either Rationalistic or Empirical, without including the word "primarily" or other words of similar import. This is done only for convenience. It can and should be understood that the word "primarily" is implied when these terms are used.

In order to develop a set of rules for living, or a set of ethics, and in order to discover a meaningful way to interpret those things which constitute my life, then, the most pressing question is whether or not any deities exist. Clearly, if one or more deities exist, this leads to a completely different view of metaphysics, ethics, and history -- a completely different philosophy, a completely different way of looking at, interpreting, and living life. For if a deity exists, that deity may give an inherent meaning to our lives. That deity, also, may give us a set of ethics to live by. Finally, a deity, if one exists, may tell us how to interpret our lives -- for instance, Calvinists historically have believed that their financial situation is dependant upon the way in which their God views them.

Historically, many different arguments have been made for the existence of deities in many different religions. In order to consider whether or not any deities do, in fact, exist, a logical first step is two consider whether or not these arguments are valid, and whether or not they actually do prove that a supreme being (or beings) exists. Arguments for the existence of various supreme beings have taken both Empirical and Rational forms over the course of the ages. It is, then, meaningful to accept either Empirical or Rational arguments when considering the question of whether a supreme being exists, because either Rationalistic or Empiral arguments could establish the existence of a supreme being.

Frequently, when considering whether or not any deities exist, theists will reach a logical contradiction or a phenomenon which they cannot explain and conclude that "the ways of God are mysterious." This position is nothing but a philosophical cop-out; it is nothing but an excuse for refusing to consider the implications of an argument because they detract from an irrational position that someone holds. It is arguments of this type which once led someone to say "the conclusion is that place where you got tired of thinking." A contradiction in a conclusion of a Rational argument is evidence of an error, either in the logic of an argument or in its premises.

Concluding that "the ways of God are mysterious" when trying to establish whether a god exists at all is also an example of a circular argument. Until we have established that a deity exists, we cannot know anything about the actions of that deity. Once the existence of a supreme being has been justified, explained, established, or proven, we can then conclude that his or her ways are mysterious. Until then, we can know nothing about his, her, or its behavior. If, in a justification for the belief in a god, the logic that the ways of this god are mysterious is encountered, it is an admission that a person has accepted the existence of the deity solely because they want to, and that the person making this argument is now trying, in retrospect, to justify their decision, either to himself or herself or to others.

Empirical Arguments

I will first consider the Empirical arguments and data, because this task will be shorter than considering the Rationalist arguments and data. An Empirical proof of the existence of god would come through sensory experience. I have had many people make Empirical arguments for the existence of their gods to me. Some Empirical arguments consist of what I call "the Argument from Miracles." These people assert that because a miracle happened in their lives, there must have been a deity to create that miracle. Examples of the argument from miracles include people who base their belief in their chosen deity on faith healers (and other miraculous recoveries from illnesses and injuries), visions that a person sees, such as the supposed appearance of the Virgin Mary in Lourdes or Fatima or the supposed appearances of images of saints in mold on refrigerators, etc., and any other type of "divine intervention." David Hume, possibly the foremost Empiricist, provides an excellent reason why we should not accept the Argument from Miracles in An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding.

According to Hume, a miracle is defined as "a violation of natural law." However, as Hume points out, all of our understanding of "natural law" comes from experience and observation, and we can never actually know what those "natural laws" are with complete certainty, because our experience and observation are essentially incomplete--there is plenty of experience that we could, conceivably, have, but haven't. There are plenty of things going on out there in the universe that we have no clue about, that we haven't observed. Hence, however much we may think we know what is and is not "natural law," we never really can be certain about this. For Hume, then, to state that something is a violation of natural law is the most heinous form of hubris; and so we can never know, with any degree of certainty, that something is or is not a miracle. We can suspect. We can theorize. But, as long as any doubts remain, we can never be certain that something is or is not a violation of the laws of nature. Therefore, we can never be completely certain that miracles do, in fact, occur.

But if I am fairly certain that something is a violation of natural law, shouldn't I assume that it is? After all, I may be the thrall of a "malicious deceiver," or I may not; but I have no way of knowing this. My life, after all, has to continue, and so I act as if there is not a malicious deceiver. The point of this logical inquiry is to establish a viable philosophy so that I may determine how I should live my life and how my life may be interpreted and understood. Absolute certainty, then, is not completely necessary; if experience strongly suggests that a miracle has occurred, I should accept that as evidence, rather than obstinately repeating Hume's argument.

However, the idea underlying this argument involves a type of hubris, as well. The events occurring in the universe are vaster in number than even the most brilliant human mind can conceptualize. We know of the law of gravity, for instance, only because of observations that we have made on earth and in the rest of the universe which is observable from our planet. We assume that gravity exists outside of the sphere of events we are able to observe. We act and talk as if it does. But we have no way of knowing this. To my knowledge, scientists are not even sure exactly how gravity works. There may be conditions which must be met for it to take effect -- perhaps there must be a certain type of present as a carrier for the force, for instance, or perhaps gravity is only effective in certain temperature ranges. We do know that gravity can be counteracted if a stronger force acts in another direction. For instance, rockets counteract the law of gravity based on Newton's third law of motion: for every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction. A rocket simply exerts a force, stronger than gravity, in the same direction as gravity -- and the "equal and opposite" reaction, which is stronger than the force exerted by the law of gravity, move the rocket in a direction opposite of the direction gravity would move the rocket. Airplanes counteract the law of gravity by applying Bernoulli's Principle -- a fluid (air, in this case) forced to move over a greater distance exerts less pressure than the same fluid moving a lesser distance in the same amount of time. The top of an airplane wing is curved, so air travelling past it travels farther and exerts less pressure. Therefore, the air below the wing exerts more pressure, and the wing is lifted, taking the airplane with it. The effect of gravity is countered by applying a greater force in the upward direction.

However, we do not know, for certain, that the law of gravity is universally applicable. It may only apply in those areas we have observed, or under certain conditions. We cannot know that the "law" of gravity is universally applicable, and so if we see something violating the "law" of gravity, we do not know, for certain, that we are witnessing a miracle. It is likely that, if a peasant from the eleventh century were to see a rocket or an airplane flying, he would think that what he saw was a miracle, even though these phenomena obey "natural laws" as we twentieth-century humans understand them. If we were to see something floating in the air, for instance, and it did not seem to apply any "natural laws" in order to do so, it is not reasonable to assume that a miracle is occurring. It is more reasonable to assume that humans to not adequately understand how natural law dictates that that object behave.

The Empirical arguments that I have heard that are not variations on the Argument from Miracles all take the same basic form: a person will tell me, "but I've felt my god in my life!" The problem with this argument is that it is not universally verifiable. "You," I will tell the person arguing with me, "may have felt your god in your life. I haven't. There are many, many other people in the world who have not felt the effects of your god in their life, or who have felt the existence of other gods in their lives." And so this argument doesn't really get anywhere. At best, it can become a subjective argument for the existence of a god; that is to say, it can become an argument of the form, "My god exists for me," "my god exists in my head," or even "by believing in him (or her or it), I create my god's existence."

Additionally, the fact that a person feels something does not necessarily establish that it is true. Certainly, many Germans in World War II felt that Hitler was a good person. Many neighbors of famous mass murders, such as Jeffrey Dahmer, have felt that these mass murderers, who they lived next to, were good people and would never, ever hurt a living soul. This does not mean that their feelings were true.

I have also heard other, more extreme empirical arguments for the existence of deities, such as "I've heard the voice of God," or "I saw God in a vision last night." However, my response to each of these is the same as my response to other Empirical arguments: I tell the person with whom I am debating that I, personally, have not heard or seen their god. How do I know, for instance, that these people are sane? Even if they are sane, how do I know that they are not deluding themselves? If they're not deluding themselves, then how do I know that they have accurately observed reality and drawn a reasonable conclusion from their observations? And if they have made accurate observations and drawn reasonable conclusions, how do I know that they're telling the truth? I don't. I can't. And so I don't accept these Empirical arguments. To me, an Empirical argument would be acceptable only if it happened to me, personally. Even then, I would need to consider the possibilities that I was insane or deluding myself.

<consider the "argument from coincidence.">

Another reason that these arguments are not acceptable is that so few people experience their deities directly. Certainly, many people observe effects, and assume that their deity is the cause (for instance, this happens when a sick person heals more quickly than normal and attributes his or her recovery to "God"), but these are only more examples of the Argument from Miracles. The people who claim to have a direct link to their deity, who "hear the voice of God" or who have "seen visions of God" are few and far between. The low number of these people, in and of itself, makes their claim suspicious. Most major world religions claim that their deity is (or that their deities are) "just." If this is true, and if these deities do, in fact, exist, then why do these deities reveal their existence only to a very few people, when, according to these religions, everyone who believes in these deities stands to gain so much? We cannot accept the idea that the ways of God are mysterious until we have established that God exists. And as we have not yet established that a god exists, we cannot accept this line of reasoning.

Additionally, this type of empirical argument seems to come, universally, from people who fall into one of three groups. I will examine each of these three groups of people individually.

First, people who have already accepted the existence of one or more gods frequently make this type of argument. We can and should disregard arguments of this type because it is highly likely that these people are trying to retrospectively justify a decision that they have already made.

These types of argument are also frequently made by people who are uneducated, or who do not accept reason as a valid method for establishing metaphysical (and, by extension, physical) truth. We should, clearly, disregard this type of argument because reason is the main distinction between humanity and the lower animals. Reason is the only thing that allows a human to live a life which is verifiably different, in a substantial way, from the lives of the higher mammals. Although animals do seem to employ reason and problem-solving skills to some extent, only humans are capable of using reason to make long-term decisions to plan their lives. Other animals may make plans for the future, such as a squirrel that collects nuts to store so that it may survive a nutless period of time in the winter or birds and whales that migrate to a warmer climate when the environmental temperature drops, but there are three distinctions that can be made between this type of behavior and the employment of reason to plan a human's life. First, squirrels and other animals which make plans for the future do so based on instinct; they have are suited for a particular environment. If the environment in which they live changes, and their instincts are unable to allow them to survive in the new environment, the animals will perish. No animal seems to be capable of using reason to change their behavior in a substantial way in order to adapt to their environment. Second, animals that use this instinctual behavior to adapt to their environment or to migrate to a new environment are incapable of planning for a period of time longer than one climactic cycle; a squirrel saves enough nuts to get him through the winter, but not enough nuts to get him through the rest of his life, or even enough nuts to get him through two winters. Finally, only humans are capable of using reason and logic (a highly developed form of reason) to actually manipulate their environments. A whale may move to warmer clime in the winter, but a human can build a small habitation, such as a house, and use fire, natural gas, or electricity to manipulate the temperature in that mini-environment.

Finally, these arguments frequently come from people who have something to gain from the existence of a god. Frequently this is something material, such as in the case of a televangelist. "God exists. Send me some money so that you can be 'saved.'" However, these arguments also come from people who are afraid that life would be meaningless if no deities existed, or people who gain a sense of security from belief in their chosen supreme being. As Kurt Vonnegut said in his novel Galápagos, "Back when childhoods were often so protracted, it is unsurprising that so many people got into the lifelong habit of believing, even after their parents were gone, that somebody was always watching over them--god or a saint or a guardian angel or whatever." Because it is entirely possible that these people are believing in something solely because they want to believe it, this argument can and should be discounted when it comes from one of them.

Rational Arguments

Having exhausted the Empirical arguments, we turn now to Rational arguments. These arguments are logical in form, and demonstrate that a deity must exist, because it is required that a deity exist in order to explain some known and verifiable fact about the universe. Some Rational arguments approach these proofs differently (i.e. backwards), arguing that such-and-such are the necessary logical consequences of the nonexistence of a deity, and that these are clearly contradicted by known fact. I have found that all of the Rational arguments which have been have been formulated (as far as I am aware) are either variations on one of the three classical arguments for the existence of God (ontological, teleological, or cosmological), or are combinations of two or all three of these classical arguments. Therefore, the validity of all of the Rational arguments for the existence of God (or a god, or multiple gods) can be examined simply by examining each of the three classical arguments for the existence of God.

The Ontological Argument

The ontological argument, one of the strangest of the Rational arguments for the existence of a supreme being, was first formulated by St. Anselm in the Proslogion. Essentially, Anselm's version of the ontological argument states that if God exists, then he is perfect. Because I can conceive of something which is perfect, that perfect thing exists, at least in my mind. But if it exists only in my mind, then it is clearly less perfect than if it existed in reality outside of my mind. Because it exists, as absolutely perfect, in my mind, it must also have an existence outside of my mind.

The problem with this argument is that it is based on simple linguistic trickery. A person reading through it who is not paying close attention might be taken in by its "logic," as might someone who is, in Anselm's words, "stupid and a fool," but a keen-minded individual who reads the Proslogion should be able to discern errors within it.

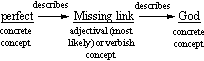

The problem is that the concept of "perfection" is adverbial. That is to say, the concept "perfect" has meaning only when it is used to modify another non-concrete argument; otherwise, it has no meaning at all. If I have a Thanksgiving turkey dinner at my grandmother's house and then say, "Grandma, that dinner was perfect," I seem to be using the word "perfect" as an adjective to describe dinner; but I am actually stating (in this case implicitly) that the dinner was perfectly tasty, or perfectly filling, or perfectly horrible. Or maybe I mean that it was perfectly wonderful to have dinner with my uncle, who I haven't seen in two years. Maybe I mean that the gravy on the mashed potatoes was perfectly textured.

Most likely, I mean most of these things and many others besides. (I don't mean that dinner was perfectly horrible; both of my grandmothers are excellent cooks.) But even if I do not, for convenience, state these things, I am saying that dinner was perfect with the understanding that my grandmother and the rest of my family will understand them, or at least that they will know that there are other things to which I am referring, whether or not they know what those things are.

If Anselm were to assert that God is green, we would know what he meant, although we might disagree. But when Anselm asserts that God is perfect, we need to ask "perfectly what?" This is because the concept "greenness" is adjectival; it describes a concrete object.

![]()

But when Anselm says that "God is perfect," and we ask "perfectly what?" we are inquiring about a missing link in his chain of reasoning:

Now, it might be replied (again, by someone who is not thinking) that God is "perfectly everything." But this is clearly impossible; even if it were not, Anselm (and other Christians, I think, for the most part) would deny this. Is God perfectly good and perfectly evil? Is God perfectly wise and perfectly foolish? I do not think that Anselm, or many other Christians, would care to argue this viewpoint.

Finally, someone (again, in Anselm's words, a person who is "stupid and a fool") would attempt to say that God is perfectly an example of all those things which are good. But this argument has a problem with it, also: it begs the question. As he was a Christian, Anselm's concept of "that which is good" comes from the Bible and other church teachings. To be sure that the Bible and other Church dogmas are completely true, and that they do establish a completely true system of ethics, we need to presuppose that something exists which can guarantee that they are, in fact, 100% accurate; that is to say, that they give us a completely true concept of historical, physical, metaphysical, ethical, and spiritual truth. For Christians, including Anselm, the force that guarantees this is God. So if Anselm, or any other Christian, were to make this assertion, he would be begging the question.

Now, take a hypothetical example of a culture whose language has no equivalent of our word "perfect." This is perfectly possible; after all, the word "perfect" is simply a word that means "the ultimate degree of something non-concrete." The concept "ultimate" is comparative; its meaning is roughly equivalent to "completely." If a culture does not have a concept of something possessing an attribute completely (being completely good, or completely green, for example), then they will have no concept of perfection. (This is hard to imagine for our dualistic, bifurcating Western minds, admittedly, but it is possible.) Anselm's proof would then have no validity: these people would not be able to conceptualize a perfect God.

This last case shows that Anselm's proof could also be subjective; that is, God could exist for some people, but not for others. And this is hardly compatible with what Anselm is trying to do; he does not simply want to prove that his God exists for him, he wants to prove that his God exists. Period.

After all, if Anselm were to knock on my door and say, "I want to show you why my God exists for me, and to make him exist for you, too," I could reply, "Anselm, I'm upstairs right now writing an essay about how no gods exist for me. Go away and take your god with you; you're stupid and a fool."

Descartes formulates a different version of the ontological argument in his Meditations on First Philosophy. (Descartes makes other arguments for the existence of God, also, but all fall into one of the three classical categories of arguments for the existence of God. Here I am concerned only with his ontological argument, which is the main argument he presents). Descartes' version of the ontological argument, which is perfectly in line with the methodic doubt that permeates his philosophy, runs as follows:

I can conceptualize something in my mind which is perfect. But I am clearly an imperfect being, so this idea of perfection could not have originated inside of me. It must have come from outside of me; it must have come from a perfect being. Therefore, a perfect being must exist. For Descartes, this perfect being is God.

Because Descartes uses this idea of "perfection," the argument against Anselm's version of the ontological argument applies equally well to Descartes' version, as well. However, I can make an additional argument against Descartes.

Descartes asserts that an idea of perfection cannot come from an imperfect being. Like Anselm, he fails to consider the meaning of "perfection." Specifically, however, he fails to consider other possibilities of where the idea of "perfection" can come from. Descartes says that, since we have an idea that something can be perfect, and we are not perfect, we cannot conceive of perfection, on our own, at all.

It is possible, however, to argue that we cannot conceive of true perfection, period. "Perfect," as I pointed out when discussing Anselm, is a comparative word. When evaluating the degree of "perfection" of a quality that a thing possesses, we merely compare how much of that quality the thing possesses to how much of that quality another thing possesses. This other thing that we are comparing the first object to must possess a greater degree of this quality of "perfection" than any other thing that we have encountered. We can then extend the idea of "perfection" of a quality out as far as we want.

It is possible that the idea of perfection, which we never really can understand (Descartes tells us that this is because we are imperfect; I think that it is because perfection does not exist) exists through extension and combination. That is to say, we can conceive of something which is "perfectly good" by taking the concept of "good" (however an individual may conceptualize it) and extending it to "infinity." "Infinity" is another concept that we can never really internalize; the concept of "infinity" exists as a convenience to mathematicians, who mostly use it as a shorthand in calculus to assist in describing what happens to the value of a function as its independent variable increases or decreases indefinitely, either in magnitude or in absolute value. The concept of "infinity" is important when a mathematician is evaluating certain limits, and limits are the basis of both the derivative and the integral. Limits are, therefore, the basis of all of calculus. An individual who does not understand the last three sentences has no idea of what the concept of "infinity" is intended to contain (and to what concepts it was intended to apply) and should use neither this concept nor its derivative concept, "perfection."

Therefore, we never can, really, understand what perfection truly is; my personal position is that no perfection exists anywhere. Certainly, if Descartes' methodic doubt is applied, it is difficult to prove that perfection of any one quality exists. To prove that perfection does, in fact, exist, it would most likely be necessary to point to something which possesses a quality (any quality) perfectly, and then to prove beyond any doubt that that object does, in fact, possess that quality perfectly (which is to say, to an infinite degree). It must, furthermore, be something which everyone can agree exists, such as a tree or other concrete object. It would, hypothetically speaking, be possible to use a non-concrete force or idea to prove that this concept of "perfection" exists, but this becomes problematic if not everyone can agree that this non-tangible thing exists. Most certainly, we cannot point to any gods as examples of perfection, since we are trying to use the idea of perfection to prove that a god exists. To use the example of a god to prove that perfection exists, and then to use the idea of perfection in an ontological argument for the existence of a god, is an example of the heinous logical fallacy of begging the question.

I have tried to cast doubt idea of perfection in general. Certainly, the casting of doubt does not establish the nonexistence of perfection; it merely casts doubt that perfection can exist.

Therefore, in addition to sharing the objections to Anselm's version of the ontological argument, Descartes' version has serious problems of its own. I turn now to thecosmological argument.

The Cosmological Argument

The cosmological argument was first formulated by Thomas Aquinas when he formulated his "Five Ways" to prove the existence of God in the Summa Theologica. The fourth argument (the argument from gradation) is ontological; the fifth argument (the argument from governance) is teleological. Therefore, the my general objections to the ontological and teleological arguments apply to the fourth and fifth arguments, respectively, and I need concern myself here with only the first three arguments from the Summa.

Although the first three arguments differ from each other in form, they all follow the same chain of logic. That chain of logic runs as follows:

Every event which happens has one or more causes. Each of those causes, in turn, has one or more causes. And each of those events, in turn, has its own set of causes. According to Aquinas, it is not possible that there is an infinite regress of causes; and so, if we trace these causal chains far enough, we will come to something which causes everything else, whether directly or indirectly, and yet was not caused by anything. This is God, whom for Aquinas is "a first mover, moved by no other," "a first efficient cause," and a "being having of itself its own necessity, and not receiving it from another, but rather causing in others their necessity."

There are two problems with Aquinas' argument.

The most glaring error is that Aquinas' argument is deterministic. (Determinism is the philosophical position that events which happen are preordained.) Aquinas does not prove that events are preordained, but rather presupposes that it has already been proven or that it is something which everyone who ever has lived, is living, or will ever live can agree on. If it has been proven, Aquinas does not say where; and determinism is certainly not something that everyone can accept.

It is not explicitly stated by Aquinas that his argument is deterministic. Rather, as I pointed out, it is presupposed that all events are predetermined. Aquinas takes this so much for granted that he does not even feel that it is necessary to mention it. Consider, however, that if I do so much as move my arm, scratch my nose, or tie my shoes of my own free will, then that is an action whose causal chain can be traced back to me--and no farther. It cannot be traced back to God or to anyone or anything else because if my will is truly free, neither God nor nature nor my parents nor heredity nor my environment caused me to move my arm, scratch my nose, or tie my shoes. It is possible that, if I have what Hume referred to as the freedom of spontaneity (that is, the freedom to choose to do as I will, but limited to the choices which have been made available to me according to the laws of reality), these factors or any others could have influenced the choice that I made. But if my will is truly free, the causal chain stops with my will. Determinism requires that everything that happens, down to my choice of clothes on the morning of December 19, 1986, was chosen for me ahead of time.

Determinism, of course, is not compatible with most forms of Christianity. The free will doctrine is a large part of most Christian theology; it is usually deemed necessary to explain, for instance, the concept of "sin." If I have no choice in what I do, then I am not really responsible for my actions; and if I am not responsible for what I do, then how can I "sin"? A Calvinist, of course, would disagree with this paragraph. But most other Christians, I think, would agree with it.

Of course, it is still possible to use Aquinas' argument to argue a non-Christian or Calvinist position, although the fact that Aquinas himself was a Roman Catholic weakens the credibility of this position slightly. (The fact that Aquinas was a Catholic does not weaken the logic, however.) But if this is done, then it becomes necessary to prove that actions are predetermined, in some way, and probably in a form which determines not only human actions but also physical events. Not only has this not been done (that I am aware of) in a way that can satisfy me, but modern quantum physics seems to say that this is impossible.

Furthermore, Aquinas does not deal with the problem of how this determinism applies to humans, but only with how it applies to inanimate objects (such as "the staff moves only because it is moved by the hand.")

Now, just because Aquinas has not proved that causality is true does not necessarily mean that it is not. My point, after all, is to determine truth as well as I am able. Since I am not an omniscient being (I can clearly determine that my ability to perceive things is limited; for instance, I'm not too sure even of what may be happening in other rooms in my house while I write this) and I don't know of anything that will guarantee that a conclusion I come to will be valid, I may make a mistake at some point in my reasoning, or I may lack experience which is necessary to come to the correct conclusion. Therefore, it is always necessary that I be vigilant against errors, and that I keep an open mind to the possibility that I have made a mistake. With this in mind, I cautiously consider whether there is any reason I should believe in Aquinas' doctrine of determinism, even though Aquinas' proof is flawed. In order to discover whether or not determinism is a valid doctrine, I do not need to prove determinism -- I only need to discover whether there is anything that strongly suggests that I should believe that events are predetermined.

Historically, there seem to be four different types of determinism that have been proposed. The first is the mechanistic, or "billiard-ball," type of determinism formulated by Descartes. Essentially, this is a type of physical causality: event A causes event B, which in turn causes event C. This is, of course, a simplified explanation, since each event in a causal, deterministic chain may have more than one cause. It is conceivably possible, in a mechanistic deterministic model, that every event is determined by every other event or object in the universe. This type of determinism is also called "billiard-ball" causality because the action of billiard balls on a pool table provides a good analogy to explain how it is supposed to work. A ball on a pool table does not have any type of free will; its moves only when something else causes it to move. During a game of pool in which the standard rules are followed, a billiard ball moves only when it is struck by the pool cue or by another ball. The inherent analogy in this type of causality is that every piece of matter, from the largest down to the fundamental building blocks, behaves in exactly the way that these billiard balls behave. The actions that people perform, then, are predetermined, since a person's actions are determined by their mind, the mind consists of atoms, and the interactions of atoms are determined by their current state and the way that they interact with other atoms, whose behavior is also determined. This presupposes that atoms do, in fact, function like billiard balls.

The problem with this type of causality is that atoms do not behave like billiard balls, however. Until the rise of quantum physics, in the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century, many people believed that atoms do behave this way and an entire religious philosophy, called deism, developed around this idea. Deists conceived of a god who was a great clock maker, who created a universe (analogous to a clock) and sat back to watch it run. According to deists, God does not interact with the world; he merely observes the events within it as they unfold. Deism developed in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and is now mostly dead. According to the ideas presented in this model of determinism, it would be possible to predict the future of any aspect of the universe if we could know, with infinite precision, the position and velocity of every particle in the universe. We could then calculate, with infinite precision, the state of any or every particle in the universe at any past or future time. Granted, this would be a monumental task, and the calculations would only be completed after the events they calculated with infinite precision had taken place, but the calculations would be accurate. The future would be predetermined.

Modern quantum physics destroys any possibility of accepting the idea of "billiard-ball" determinism. It has shown that atoms do not interact in a simple, preordained way and that they do not interact like billiard balls at all. In fact, quantum physics has shown that it is impossible to predict how even the simplest of particles -- the electron -- will act in any given set of circumstances. It is possible to predict the probability that a subatomic particle will act in a given way, but it is never possible to predict with complete accuracy how it will actually act. Quantum physics has also shown that the very act of observing a particle alters its position and its velocity, the two bits of information that we would need to gather in order to predict the behavior of the particle in the future, and that the more closely we observe a particle's position, the less closely we can observe its velocity, and vice-versa. Finally, quantum physics has shown that the "particle" conceptual model of the basic building blocks of matter is inadequate -- atoms and subatomic particles sometimes act like waves, and sometimes act like particles. They always seem to have the characteristics of both, and how they act seems to depend on how we expect them to act.

All of these things which have been demonstrated by modern quantum physics seem to strongly suggest that mechanistic determinism is unacceptable. I turn now to spiritual determinism.

The basic idea behind spiritual determinism is that there is a god who predetermines all events ahead of time. Since we have not yet established the existence of a god, we cannot assume that spiritual causality is a valid philosophical viewpoint. To use spiritual causality is an example of begging the question.

Althusser calls the third type of determinism "Spinozist" causality, after Baruch Spinoza, the seventeenth-century philosopher.

<Discuss Spinozist causality.>

Finally, the fourth type of determinism is behaviorism. Behaviorism states that the actions of a person are determined completely by his or her environment, past and present. The past environment includes upbringing and all other forms of experience; the present environment includes all sensory impressions that a person is currently experiencing. According to a behaviorist, such as B.F. Skinner, every action that a person performs can be explained by these past and present circumstances and sensory impressions. If I scratch my nose, it is because my nose itches; and the way that I scratch my nose is determined by such things as how I have seen others scratching their noses and how I evaluate those others, whether I wish to emulate or avoid emulating them, and many other things. If I refrain from scratching my nose, even though it itches, it is because something in my present or past experiences requires that I not scratch my nose. Perhaps, according to my upbringing, it would be impolite to scratch my nose in the social situation I am currently in.

<Epistemological refutation of behaviorist psychology.>

To point out the second error in Aquinas' argument, I will assume, for the moment, that determinism is true. (This has not been proven, remember. But I'll grant it to point out another flaw.) Even if determinism is true, then, Aquinas' argument rests on his idea that there is no infinite regress of causes; that is, his argument rests on the idea that there cannot be infinite regress of causes. This is closely related to (and, I think, dependent on) Saint Augustine's idea that time is not infinite and that it must have a starting point. But, when considering this idea, I wonder to myself: Even if determinism is true, why is it necessary that there not be infinite regress of causes? I will here consult Aquinas' Summa itself for his reasons.

In his "first and most manifest way" for arguing the existence of God, Aquinas states that there can be no infinite regress of causes because "then there would be no first mover, and consequently, no other mover." If we assume that Aquinas meant to place the emphasis on the first part of the sentence, then essentially, Aquinas believes that there cannot be infinite regress of causes because if there were, God would not exist. Therefore, Aquinas presupposed the existence of God in order to prove the existence of God. Once again, we have found that a theological argument for the existence of God is based on the logical fallacy of "begging the question."

An alternate interpretation of this "first and most manifest way" (which avoids this logical fallacy of begging the question) would assume that Aquinas intended to place the emphasis on the second part of the statement. That is to say, rather than assuming Aquinas meant that the reason we need to conclude that there is a god is because otherwise there would be no first mover (which is a circular argument), we can assume that Aquinas meant that we need to conclude that there is a first mover because otherwise nothing would move. This, in fact, seems to be the more sensible approach, and to me it seems likely that this is what Aquinas intended. This involves the logical fallacy of begging the question: the idea that, if there is no first mover, nothing would move, is exactly what Aquinas is trying to establish. To use the very "fact" that he is trying to prove as the crucial step in his "proof" is a heinous logical oversight at best.

In his second way, Aquinas says that there can be no infinite regress of causes because "if in efficient causes it is possible to go on to infinity, there will be no first efficient cause." Again, Aquinas is begging the question--he assumes something which has not been established simply because if he doesn't, his proof is not possible. In order to facilitate his proof (and, in fact, to make it possible at all), he assumes something highly questionable, which is a philosophical point of contention that has been by no means settled, for the sole reason that if he does not do this, he will have to abandon his work.

In his third way, Aquinas explicitly refers to the reasoning about infinite regress of causes that he establishes in his second argument. There is nothing new here.

Aquinas, therefore, believes that there is no infinite regress of causes simply because he wants to. There is no reason to believe this which does not beg the question.

Clearly, then, the cosmological argument is not logically valid. I turn now to the teleological argument.

The Teleological Argument

The essentials of the teleological argument were most famously argued by William Paley in his book A View of the Evidences of Christianity. This form of the teleological argument is commonly referred to as the Watchmaker Argument. There were teleological arguments before Paley and there are teleological arguments which do not involve the watchmaker analogy, but the essential characteristics of the argument remain the same. The argument runs as follows:

I am walking down the beach, and I find a watch lying in the sand. Looking at the watch, I assume that it must have been created, rather than occurred naturally, as the parts are intricate, ordered, complex, and lo! they work together marvelously well. In this argument, which is an allegory, the watch is analogous to the earth, which is assumed to be an ordered system with parts that work together in a complex, yet obviously ordered and planned, manner. And, Paley tells us, if a watch has a creator, then the earth, which is inconceivably more complex, must also have a creator as well.

There are at least three problems with the watchmaker argument. One underlies its foundations, one is a problem with the logic itself, and one is a problem with its implications.

The first problem with the watchmaker argument is in its underlying assumptions. Basically, Paley assumes that the earth is an ordered system, with parts that work together in a predetermined way. To me, however, observation doesn't seem to bear this out. I do not think that the parts of the systems of interactions in the earth work together in an especially ordered, preordained way. As David Hume said in Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion, "The world plainly resembles more an animal or a vegetable, then it does a watch or a knitting-loom." I tend to agree with Hume's argument here; a watch has a group of parts which interact in a complex, predetermined way, yes, but that way does not change at any time; whereas the way that the systems of a living creature, whether animal, mineral, moneran, or other low form of life, interact can and does change. If this change happens only in minor ways in individual organisms, it happens in major ways in interactions between organisms over the course of time through evolution. The way that the systems of the earth interact also changes: if a new organism, for instance, is released into a closed ecosystem, then that ecosystem, if it is to survive, must adapt its functioning to that organism (and the organism must adapt to the ecosystem).

The second problem involves the logic inherent in the argument. When I find the watch, I assume that it has a creator because it is ordered. We need to examine the implications of this argument for a moment. The functioning of the watch is ordered when it is compared to what? The argument implicitly states that the functioning of the watch is ordered when it is compared to the functioning of nature. In the first part of the argument, Paley asserts that nature is more disordered than the watch; in the second part, he asserts that nature has the same degree of order as the watch does. His argument, therefore, is internally inconsistent.

Finally, the third problem I have with this argument is in its implications. Assuming, for the moment, that the teleological argument is logically valid (which it is not, as I have already shown), consider that the God whose existence the argument attempts to establish must, of necessity, be more vast and amazing than the world. The argument, then, applies even more strongly to God than to the world itself. That is to say, if the watchmaker analogy establishes that the world had a creator, it establishes even more strongly that the creator of this world has a creator; and that the creator of that creator has a creator; and so on ad infinitum. The argument for a creator gets stronger and stronger with every stage of regression that occurs. Most Christians, at least, would, I think, find this to be absurd. (In fact, Aquinas, who formulated the cosmological argument, based this entire argument dependent upon the fact that infinite regress of causes is impossible.)

It is possible to argue that a teleological argument which does not use the watchmaker analogy could be valid. I now consider that possibility.

Essentially and in its simplest form, the teleological argument states that the world must have a creator because it is so amazing and complex. What the teleological argument is stating is that it is obvious that the universe has a creator. As Saint Augustine said in the Confessions, "We look upon the heavens and the earth, and they cry aloud that they were made." It is, then, necessary to examine this statement.

If the heavens and the earth cry aloud that they were made, then why are there people who doubt it? Many people, when looking around them, simply see no reason why a deity is required to explain what they find in the world. In their song "Competition Smile," the musical group Gin Blossoms said, "Looking up, I saw nothing/ But blue in the bluest sky." Many people seem to think that the vastness and amazing complexity of the universe is not, in and of itself, an acceptable argument for belief in a deity.

Atheism, a Malicious Deceiver, Phone Leprechauns, and Occam's Razor

It might be replied that atheists, for instance, are actually aware of the existence of a deity, but choose to ignore or deny that supreme being. There are, in fact, people who take this position, and some go so far as to equate atheism with devil-worship. Although this is not true, it is impossible to argue with a person who believes, based on "faith," that they have the corner on eternal truth. However, these people are often, consciously or subconsciously, reverse-justifying a decision they have already made--they have "faith" that there is a creator, and so, to them, it is obvious that they universe must have been created. (I will discuss faith later in this essay.)

However, for the moment, let us assume that atheists are, in fact, merely obstinately denying the existence of a god. How, then do we explain agnostics, people who simply do not claim to know whether or not any gods exist? Unlike atheists, agnostics cannot be accused of denying the existence of a god, because they do not claim that no gods exist. Rather than being obstinate, one way or another, they simply admit that they don't know.

And if the heavens and the earth cry aloud that they are made, then why are there so many different religions which teach so many different things about the nature of their creator or creators? Every artist who creates something substantially new has a distinctive style which can identify that artist and differentiate him or her from other artists. In many cases, we can tell much about the nature of the artist, or at least his or her psychological makeup, just from examining and scrutinizing that artist's works. If, then, the universe has a creator, we should be able to know what that creator thinks and what that creator's psychology is. Since every religion which asserts the existence of a creator has an ethical system describing the wishes of that creator regarding how humans should live their lives, it should be possible to examine the universe, learn about the mind of its creator, and understand how that creator wants us to learn. From there, we could decide which religion, if any, is the "true" religion by comparing what we have learned about that creator's psychology. And yet, no religion in the world has even a simple majority (Christianity comes closest, capturing the minds of 32% of the world's population), let alone a monopoly.

The only explanation I have heard explaining the existence of atheists and agnostics from a religious context requires that we re-introduce Descartes' "malicious deceiver" in the form of a force of nature or supernatural being. In my experience, this usually happens in a Christian context when Christians claim that non-Christians are deceived by the fallen archangel Satan.

However, there is no reason to suppose that a malicious deceiver exists while we are still trying to establish the existence of a creator. The existence of a malicious deceiver is unverifiable in this context, because there is no evidence that a malicious deceiver exists apart from a creator, the existence of a creator is what we are trying to establish, and if this argument is true, the existence of a malicious deceiver renders it impossible for the majority of humanity to understand that the universe was, in fact, created. Since this argument is unverifiable and leads nowhere, we need to toss it out if we are to formulate a meaningful philosophy.

One argument against a malicious deceiver is that Descartes, himself, was not able to disprove that a malicious deceiver exists, despite the fact that he was absolutely certain that there was no such deceiver. In fact, because he was not able to disprove the existence of the malicious deceiver, Descartes was never completely able to prove that anything exists outside of his own mind. The only reason that Descartes believes so strongly that no malicious deceiver exists is because he states that "from the fact that God is no deceiver, it follows that I am in no way mistaken in these matters." The first and most obvious problem with assuming that Descartes cannot be mistaken because God is not a deceiver is that we have not yet established that God exists! The second problem is that Descartes himself criticized those who proceed with their arguments by "arrogantly claiming for themselves such power and wisdom that we attempt to determine and grasp fully what God can and ought to do." If Descartes criticizes others (atheists, in this case) for attempting to understand the motivations of God, then he himself certainly has no right to claim that God would not let him be deceived; after all, since he clearly doesn't want to be arrogant and claim for himself such power and wisdom that he knows what God can and ought to do, he can't know that God does not have a motivation for letting him be deceived, or even that God is capable of preventing him from being deceived, should someone else, such as Satan, wish to deceive him!

The single best reason to reject the "malicious deceiver" argument, however, is a rule called Occam's Razor. Occam's Razor is a logical rule for use in deductive and inductive reasoning. It is simple, as it consists of only one sentence. However, its implications are profound. Occam's Razor, in its original form, runs like this:

"Do not multiply entities needlessly."

Essentially, this means that I should not postulate the existence of an "entity" (defined by The American Heritage Dictionary, Second College Edition, as "The existence of something considered apart from its properties") to explain something if I can explain that something in any other way. One example should suffice.

Let us say, for instance, that you and I are discussing this by phone rather than in the form of an essay that I have written and you are reading. Let us suppose further that you ask me, "How do phones work, anyway?" (I know that most people would never ask me this, as I think that anyone who has read this far is, most likely, intelligent enough to have at least a basic conception of the operation of a telephone. I use this only as a convenient example.) There are, then, at least two basic replies that I could make.

The first is that, when I speak to you on the phone, a microphone picks up my voice, transforms the vibrations in air into an analog (continuously variable) electrical signal, which is transmitted by the phone system to the earpiece on your phone, where the analog signal is reverse-processed and turns back into vibrations of air molecules. You, then, hear my voice, even though you live in an area which may be on the other side of the globe from where I am talking to you on the phone.

The second argument that I could make is that a magic leprechaun (or elf, or unicorn, or whatever--I will continue to use the example of a magic leprechaun here) lives in every phone, and when I speak, the leprechaun transports himself from my telephone to yours -- Poof! -- and exactly mimics my words and voice from the earpiece of your phone before quickly returning to my phone's mouthpiece, ready to receive the next sentence. Assumedly, you have a similar magic leprechaun in your phone who mimics your voice when you speak.

Can I disprove the magic leprechaun theory? No. Neither can you, no matter how absurd it may be or how hard you try. Even if you come up with tests which suggest that there are no such leprechauns in the phones, I can adjust the parameters of my belief in the leprechaun phone system. Say, for instance, that you and I both buy cellular phones and we stand where each of us can see the other, then one of us calls the other's cellular phone number. We also assume that the only way that you and I can hear each other is through our telephone communication, even though we can see each other, live and in person, distinctly. Perhaps there is a sheet of soundproof glass between us. Finally, let us further postulate that, while we are talking on the phones and watching each other, you notice that my voice comes through your earpiece at the same time my mouth is moving, and you tell me that the leprechaun couldn't possibly exist, because if he did, he would have to wait until I had finished saying something (whether a sentence, a word, a syllable, or a single sound) before he could transmit it to you, and you would then notice a lag between when I said something and when you heard it. I can simply assert that the leprechaun move backward and forward very quickly --in fact, more quickly than your senses can detect. After all, he (or she) is a magic leprechaun; why not assume things like this?

But I don't even need to stop there. Once I have assumed the existence of a magic leprechaun, I can adjust his supposed abilities in any way that I so desire. Even if you invent a device that measures time with infinite precision, and say that there's no way that the leprechaun could get from my mouthpiece to your earpiece without even an infinitesimal lag (which your machine would detect), I can change the rules my leprechaun operates by and say that, once I have finished speaking an infinitely small fraction of a syllable, my leprechaun travels backwards in time to when I began to speak, as well as travelling in space from my mouthpiece to your earpiece. You open the phone, and see no leprechaun? He's invisible. Or hiding. As a matter of fact, it would be better not to open the phone at all, because then the leprechaun might get angry, and not let you use your phone anymore. You talk to the phone manufacturers, and they tell you they know nothing about these leprechauns? Maybe they're part of a magic leprechaun conspiracy. Amazingly enough (I could claim), there's proof of this: they put those fake microphones and wires and speakers in the phone to try and cover up the existence of phone-leprechauns.

So you can see, there's no way for you to disprove the existence of magic leprechauns who operate the phone system. I could even claim that, although I have faith in leprechauns, you have faith too: you have faith that the leprechauns don't exist in the same way that I have faith that the leprechauns do exist.

Arguments of the phone-leprechaun type are the reason why the burden of proof is on the debator who asserts the existence of anything. This, of course, is where Occam's Razor comes in handy: it allows me to shave away all of this phone-leprechaun baloney. I could certainly accept the existence of phone-leprechauns; however, if I apply Occam's Razor ("do not multiply entities needlessly") to the problem, I will choose the first option (the one about conversion of vibrating air particles to analog signal waves and vice-versa).

It may seem that I've gotten a little far away from the topic at hand, but I haven't. My point is that if I can explain a phenomenon without postulating the existence of an entity, I should do so; in fact, there is no reason to do otherwise. And Occam's Razor is what makes Rationalist arguments for the existence of God so fragile: if a Rationalist argument asserts that God must exist, because the existence of God follows logically from fact X, all that is needed is to provide one other argument that does not postulate an entity for the existence of fact X to destroy that particular Rationalist argument. In addition, a Rationalist argument for the existence of God can be destroyed by demonstrating an error in reasoning; if a Rationalist argument states that God must exist, because fact X says so, and fact X is based on fact Y, then if I can destroy the connection between X and Y, or between X and God, I have destroyed the argument.

Does this have anything at all to do with the existence of a malicious deceiver? Certainly.

Remember, Occam's Razor strongly suggests that if we can explain something without postulating that an entity exists, we should do so. If we need to postulate a "malicious deceiver" in order to believe that the universe was created by a deity, then Occam's Razor strongly suggests that we have a very weak philosophical position. I have already cast doubt on the validity of the teleological argument. The only thing saving it right now is the possibility that a malicious deceiver exists. But if we can explain the complexity of the universe -- which is what the teleological argument claims a deity is necessary to explain -- without postulating that a deity exists, then there is no need to postulate either that a deity exists or that a malicious deceiver exists. In fact, if we can explain these things without postulating the existence of these entities, then Occam's Razor obligates us to do so; if we refuse to do so, then we need to give up reason as the foundation for our philosophy.

"Evolution"

Science has provided us with a set of explanations which does not require that we believe that any supreme beings exist. Creationists frequently refer to this set of explanations collectively as "evolution."

This usage of the word "evolution" is often incorrect. Technically, evolution refers only to the process which describes how a species changes over time. Creationists, however, frequently use the word to refer to any scientific theory which is contrary to strict biblical teaching, including theories regarding the origin of life, which should, strictly speaking, be called "abiogenesis," and theories about the origin of the universe, which belong to the scientific realms of cosmology and astronomy. Evolution, as defined by Chris Colby in Introduction to Evolutionary Biology, Version 2, is simply "change in the gene pool of a population over time." However, for the purposes of this discussion, I will grit my teeth and use the word "evolution" in its creationist sense to mean "any explanation for the origin or nature of the universe or humanity which does not require religion and is based on science."

The Big Bang theory is an adequate explanation of the universe. According to the Big Bang theory, all of the matter which currently exists in the universe existed in a supercondensed particle before the universe, as we now know it, came into being. This supercondensed particle exploded, and the universe as we now know it gradually came into being as the matter cooled.

There is evidence that the big bang theory adequately explains the origin of the universe. One piece of evidence which strongly suggests that the Big Bang theory may be correct is the red shift of the universe. Faraway galaxies appear to be red when viewed through a telescope. This is an example of what physicists call the Doppler effect: the frequency of the waves of light appears to change due to the motion of the source of the light waves (the faraway galaxies) or the motion of the observer (our galaxy is also moving away from other galaxies, and we move with our galaxy). Since we and the light source are moving farther apart from each other, the light waves appear to be shifted in the red direction (that is, they seem to have a lower frequency).

Many creationists, when discussing the Big Bang theory, pose a question which they believe will defeat all possible arguments of the Big Bang type. The question, in its simplest form, is this: "Oh yeah? If the universe came from the explosion of a supercondensed particle, then where did the particle come from?" There is at least one possible theory of which I am aware, called the "Big Crunch" theory. According to the "Big Crunch" theory, gravitational forces acting between all the pieces of matter will eventually overcome the kinetic energy (energy of motion) of the matter in the universe (which is expanding, remember) and draw all of the matter back together into another supercondensed particle. After this happens, there may be another Big Bang to start things off again.

If the Big Crunch theory is true, then it is possible that the universe has simply gone through a series of Big Bangs and Big Crunches. This does not explain where the matter in the universe "came from." But there is no reason that the matter in the universe had to have "come from" anywhere at all. Many creationists assert that the matter in the universe "must have come from" somewhere. They then assert that this matter that "must have come from" somewhere came from God, who did not "come from" anywhere, but has always existed. Rather than assuming that an amount (perhaps finite) of dead matter with conceivably knowable properties has always existed, they assume that an infinite, all-powerful, all-knowing deity, who is beyond our comprehension, has always existed. Occam's razor suggests, however, that we accept the explanation which does not require us to assume that an entity exists. This explanation is the Big Bang theory.

<discuss abiogenesis.>

The theory of evolution, in its technical meaning, provides a better explanation for the nature and diversity of current species than does the creationist standpoint. Kurt Vonnegut discusses creation and evolution, briefly, in his novel Galápagos. He mentions the voyage around the world taken by Charles Darwin on the ship Beagle, and discusses the thoughts that Darwin had upon evolution while he was on the Gal?agos islands. Particularly, Vonnegut mentions that wonder that Darwin experienced upon seeing that the only birds on the island are fifteen species of finches, many found nowhere else in the world. Each species of finch is adapted to feed on a particular type of food. Some finches feed on seeds; some finches behave like woodpeckers and search for bugs; some finches even obtain their nutrition from the blood of animals. According to Vonnegut,

What was so thought provoking about all sorts of Galápagos finches to young Charles Darwin, though, was that they were behaving as best they could like a wide variety of much more specialized birds on the continents. He was still prepared to believe, if it turned out to make sense, that God Almighty had created all the creatures just as Darwin found them on his trip around the world. But his big brain had to wonder why the Creator in the case of the Galápagos Islands would have given every conceivable job for a small land bird to an often ill-adapted finch? What would have prevented the Creator, if he thought the islands should have a woodpecker-type bird, from creating a real woodpecker? If he thought a vampire was a good idea, why didn't he give the job to a vampire bat instead of a finch for heaven's sakes? A vampire finch?

The theory of evolution proper also better explains other observable facts. For instance, DNA is a molecule which encodes genetic information. The development of an organism is controlled by its DNA; a change in the DNA of an organism will affect its development. The DNA of humans and other primates is very similar; the primate most closely related to humans is a type of chimpanzee. Its DNA structure is more than 99% similar to the DNA structure of humans. It could be argued that DNA is a structure created by God for the purpose of transmitting genetic information from one generation to the next, and that the reason the DNA is so similar is that the morphology, or physical appearance and structure, of humans and these chimpanzees is so similar; that is, the fact that the appearances are similar is a consequence of the fact that the DNA is so similar. This would be a perfectly acceptable argument, except for two things.

First, even though this explanation is plausible, Occam's Razor strongly suggests that we should adopt the solution which does not require that we postulate an entity, such as "God."

Second, not all of the sections in a molecule of DNA are used for coding; that is, DNA is the molecule which controls the physical appearance and structure of an organism, but only some of the DNA is actually used to do this. If God created DNA to transmit genetic information, there is no reason to believe that he (or she or it) would create extra, "junk," sections of information. It's like writing a book and, in certain sections, simply typing gibberish, preceded and followed by meaningful text. Also, there is no reason that, even if God were to create gibberish sections, they would be so similar between humans and apes. And yet, the "junk" sections of DNA are very similar in the two species.