|

|

|

|

| - What's New

- About Chapter 108 - Contact Us - Calendar - Newsletters - Projects and Planes - Safety/Regulations - Scrapbook - Young Eagles - For Sale - Links - Home |

Technical Sergeant Jim Brown

U.S. Army Air Corps (ret) Bataan Death March Survivor Presentation to EAA Chapter 108

If I live to June 12, 2000, next month, I will be 79 years old.

Is there anybody here my senior? (Lou Henderson raised his hand.)

During these 79 years I have had two rounds of pulmonary tuberculosis,

two rather sever cases of pneumonia. I’ve had throat cancer, lung

surgery, four colon surgeries, two plastic eyeballs, and an eyesomdectomy*.

I mention this is to demonstrate to you that the only reason I’m here tonight

is that I was just too confounded contrary to let the Japs do me in.

There is something else that brought me home that I think I should mention.

There was a Captain Coffee that was a Viet Nam prisoner for about six years,

and he explained that there were four faiths that brought him home.

There was the faith in himself, the faith in his fellow man, his faith

in his country, and faith in Almighty God. I had these four attributes

and I one other thing. I had this dream to come home to, my wife

Pauline.

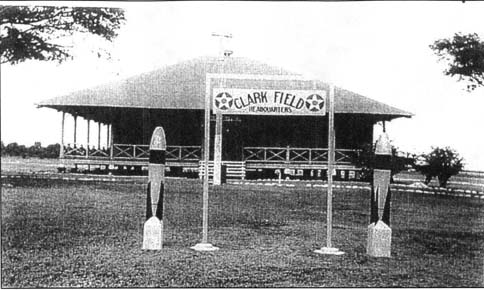

I joined the Army Air Corps at Chanute Field in June 1939 on my eighteenth birthday. I went to technical school at Chanute. Upon graduation I was sent to the Philippine Islands. I arrived July 20th 1940 at Clark Field. At that time Clark field had about 106 men and officers. There were 66 of us that came in and which kicked the number up to roughly 172. In those days we had what were called composite groups, I don’t know if any of you gentlemen are familiar with those. The Fourth Composite Group was composed of the 28th Bomb Squadron, the 3rd Pursuit Squadron, the 2nd Observation Squadron, and the 20th Air Base Squadron. The 20th Air Base Squadron serviced all the Squadrons and was stationed at Nichols Air Base. I was on detached duty for orders, quarters, and rations at the 28th Bomb Squadron.

Clark Field, circa 1938

Clark Field, 1938 In those days we had some rather obsolete aircraft. I have some pictures that are being past around. There was the Martin B-10 Bomber, which was made in 1932, assigned to the 28th Bomb Squadron. The P-26A, the Peashooter, was assigned with the Pursuit Squadron. The 2nd Observation Squadron flew the O-19 and O-46 aircraft, and a few miscellaneous airplanes sitting around.

B-10b Bomber Aircraft We towed targets for the tow target group with the B-10’s, and we had an OA-9 and an OA-4 observation amphibians that were mostly used by the officers for fishing trips to some of the nicer little lakes around the island.

We had some pretty nice times at Clark Field in peacetime. Then I transferred down to Nichols Field to the 20th Pursuit Squadron after it arrived over here in late 1940. I went down to Nichols on March the first and joined the squadron. At that time the squadron was flying only P-26A aircraft. A little later we confiscated a shipload of Simanese (Thailand) Severski P-35A aircraft. These aircraft had no machine guns installed in them and they were equipped with metric instruments. I was made an instant instrument mechanic and went to the air depot to remove the metric instruments and install inch system instruments in those aircraft. The armament boys modified the wing roots and put a couple of 50 caliber machine guns in the wings of the P-35's. We kept these aircraft until just before the war, at which time we got a squadron of P-40-B aircraft. The P-40-B's had four 30’s in the wings and two 50’s that fired through the propeller. That was the equipment my squadron was flying when the war started.

We were sent to Clark Field for extended maneuvers on the first day

of July 1941 and lived in hangar number one, which you can see in the picture.

The entire squadron lived in this hangar. We drew lines on the floor

to designate the first three grade accommodations and the private accommodations.

We lived there until a week before the war started. At that time

we moved into new bamboo shacks, which was the first time I was in a bed

with a roof over my head like that since we arrived up there. We

were in those accommodations for one whole week before things happened.

We scrambled for our foxholes. They hit and just blew the hell out of the place. And then an estimated 90 fighters came in and finished it off the attack. My Squadron Commander, now LtGeneral Joe Moore, took off with two wingmen, a pilot by the name of Edwin B. Gilmore and a one by the name of Randel D. Keator. They shot down four planes. I heard they were going to court-martial them for taking off against orders. Later, rumor had it that in the end, they gave the three pilots the Distinguished Flying Cross. The next four pilots in my squadron were killed on the ground during the takeoff run. After the Japs left I think we had a total of five aircraft which remained in flying condition in my squadron. The three that were in the air and two that were in the bushes that they didn’t get. They were NOT…I SAY, NOT, lined up wingtip to wingtip. Our planes were dispersed all over a large field and pushed back into the jungle all the way around. That they were not lined up wingtip to wingtip as you hear. That rumor is absolutely not true. We worked there from the eighth until the 24th of December operating against the Lingayen landing. The Japs had brought in 90 ships up there and they were unloading them. We kept our aircraft in the air continually. The planes came in with holes punched in the wings and we put cloth patches on metal aircraft. We would glue the patches down and they would stay. MacArthur had orders when the war started to initiate what was called the Orange Plan. The original plan was devised in 1902 when Admiral Dewy took the Philippines Island from the Spanish. The Orange Plan said we would pull all of our equipment, our food and our troops into the Bataan peninsula, put up a perimeter line, and hold off any enemy until ships could come in from the United States with the reserves, ammunition, food and supplies. Well, at the last minute, MacArthur decided not to follow this plan, so he dragged all his supplies up with him up to Lingayen in Northern Luzon, strung them all the way up there. We had warehouse built in Bataan to hold this food and some of them were sitting nearly empty. Let me mention right now that the Philippine Scouts were some of the finest troops to ever take the field. They were wonderful, all of the different regiments of Philippine Scouts . For those of you not familiar with this organization, they were Philippine troops and American officers in charge. When a boy was born to a Philippine Scout father, as soon as he could walk, he would start to get training in the field his Daddy was in. When he was eighteen years old he was a combat ready soldier. Our government in Manila sent a selected number of Filipino’s to West Point every year. I forget the number. I understand these officers would come back and finish their enlistment, then take a discharge and join the Philippine Scouts as a Sergeant. That’s the difference between the Philippine army and Philippine Scouts. On Christmas Eve, I was ordered to retreat down into Bataan. I rode down in a Pampanga Bus Company bus. This was a large old straight axle truck with a roof on it and slat seats. That’s how I went down to Bataan. My squadron landed at Marivelas Field. We were suppose to have a whole gaggle of a A-20’s come in and we were suppose to get the field ready and the revetments built, because any day the airplanes were suppose to start rolling down the runway. Four months later none of the planes had arrived, nor had any of the medicine or food -- nothing. But we fought the Japs for four months there. We completely ran out of food. We ran out of ammunition. We ran out of medicine. Over fifty percent of the men were sick with malaria and diarrhea. Then MacArthur was sent to Australia. He was ordered to Australia don’t cha know. So he got on a PT boat. He took his Master Sergeant gun bearer. The only thing he had ever done in the service was to clean the general's 45. MacArthur took his wife and his kid, and he left us. He left us with strict orders not to surrender. Well, when we ran out of all of the food supplies on Bataan, we were issued the cavalry horses. These were butchered and eaten, then the mules. After a couple of days boiling, you could swallow one of those mules. We ate monkeys, dogs, lizards and whatever you could dig out of the ground. When that was all gone and there was nothing left General King surrendered. That was on April the ninth. A Jap tank came by and ordered us to go down the flying field to surrender. When we got there we were lined up and blankets were spread on the ground in front of us. We were ordered to place any item of gold on the blankets under the penalty of death. Being a southern Indiana pig farmer, I was just a little bit bull headed, so I took the watch that my dad had given me for graduation and crushed it between a couple of rocks and threw the smashed pieces in the underbrush. My mother had died shortly after I went into the service. She only lived for about ten minutes after she was stricken but she told Dad, “Jim take my wedding band off and give it to Bus. If his bride chooses to wear it, it’s my prayer that their lives will be as happy and productive as ours have been.” Well, I had the ring, and I wasn’t about to give it to a Jap. So I taped it under my armpit with some adhesive tape. The second day of the march a Jap guard found it. I thought he was going to kill me. I kept spitting on my finger and pointing toward Heaven. I had seen people do this in a movie but I didn’t know what it meant. He looked at me. I know now what he said, he said “Oh Mama. Mama awory” (Mother dead). Well I thought it was a good idea to agree with him and I said “yup”. He told me to tape this ring just above my anus, that no Jap would ever feel there. Show the people the ring sweetheart. (Mrs. Brown was in the audience and held the ring up for all to see.) I started the Death March on the 11th, lets see captured on the ninth, in place on the airfield two days, started on the 11th. I got to San Fernando Pampanga on the 19th. I was there two nights. We were then placed on railroad cattle cars and taken to the town of Capas. From there we marched on to O’Donnell, the first prison camp. During the nine days of the march I was issued two balls of rice, that was all from the Japs. Along the national highway were beautiful artesian wells. We were not allowed access to the wells. Guards were placed around the wells to deny us the water. However we could dip anything we wanted to out of the ditches. I carried a rusty five-gallon gas can on my back the entire march. Toward evening if I could, I would dip up a gallon or two of water. If I could get to a fire I would boil it and fill mine and my buddy’s canteen and canteen cup and wash our face if there was had any left. I never drank a drop of water on the march that I didn’t boil other than once or twice, when I could get to an artesian well that didn’t have any guards stationed around it. One of the punishments they would make us endure on the march was the Japanese sun treatment of submission. They would set the first guy down on the ground with his legs spread and set another guy down right in his crotch and pack them just as tight as they could for a row. Then start another row. They would make us take our hats off. Then we were made to set there in the boiling noonday sun for an hour or an hour and a half. That was the sun treatment of submission. Then we would get up and march again. They used us as hostages or shields between them and the guns on Corregidor. Corregidor was in sight of the national highway at Bataan. As we were being marched out of the compound in columns of four, the Japs were bringing in all of their artillery, horses and other equipment down into Bataan. They had built one gun implacement made out of sandbags. It must have been six feet high. A Battery of Artillery on Corregidor opened up with a firing box of four on the hill. The very next round landed exactly in the middle of this gun emplacement. When it exploded you could see the breech and wheels of the gun, along with the bodies of the gun crew rise up above the pal of the smoke, sort of hang there for a moment and then they settled back down. Unfortunately several of our guys were hit when the shell went off that close to the road. I helped carry a Captain who had a terrible wound in one hip. He would walk on one leg with a guy holding him up on each side. When we would get tired we would pass him to someone else. He made it through the war and I saw him a few years ago. After we got to San Fernando at the end of the march, we were held in

cattle corrals for two days. They did give us rice twice a day and

we did have water. Then they packed us in railroad cars to take us

to Capas. The cars were narrow gauge Philippine railroad cars,

small boxcars. With bayonets they packed a hundred men in the cars

and locked the doors. Most of these were steel boxcars.

I can’t imagine the hell those prisoners went through. I got into

a cattle car with slat sides. Being railroad wise, I lived by the

railroad tracks, I got back in the corner where the overhead vent could

let air in. I had a reasonably comfortable ride if you could call

it that. When we went through Angelis City, any of you guys know

Clark? Angelis was the rail center for Clark Air Base. The

Queen of the prostitutes was Carabao Annie. As the train pulled through,

Carabao Annie was on the docks. She went to each car one at a time

and ask, “Hey anyone see Joe P? Joe in there? You see Joe you

tell him I do my part. I give every Jap come my place the clap."

They had a row of rooms, how do I explain this to you? There was a row of rooms about 12 by 12 and one side was open. Three of the sides were covered and had a roof over it if you get the picture. They put our doctors in there for sick call. One of the doctors was Col. Worthington, who was a horse cavalry veterinarian. Old Doc had him a stall right along with the MD's and the PHD’s you know what I mean. I think he did more good than any doctor in camp. A guy would come in and say “Oh my God Doc, I haven’t had a bowel movement in ten or twelve days. "Son have you eaten anything beside what the Japs have given you." " No I haven’t." Doc would say, "if you have a crap in the next ten or twelve days you will be lucky. Let me tell you, go down and get a half a spoon of wood ashes and mix it in a quarter of a canteen cup of water and mix it up real good and drink it. I believe you will find it will help you." Next guy would come in, “Oh Doc. I’ve got the dysentery something awful, I’m just going constantly." Same Doctor, same prescription. You couldn’t find a spoonful of wood ash in the whole camp. After the war, Doc was murdered in Brownsville, Texas because he loaned a neighbor a garden hose. When the guy wouldn’t bring it back, Doc went to get it and was shot in the head. Doctor Worthington was a wonderful man. Anyhow, I was in this camp from April 21st to May the fifth. At this time I was sent on bridge detail. The first night I was at the camp I think one guy died. The day I left, I think they said 141 died and then it got worse. This was at O’Donnell. I went out on the bridge detail at Gapan, not Japan, but Gapan, a city to the east of the camp. There was a five span bridge located there and our engineers had blown three spans. They took 200 of us up there as slave labor to rebuild this bridge. We were there from May the fifth until June 21st or so. At that time I think 89 of the guys had died, and the ones that were left were so sick that they could not do any work. They hauled us back to the new prison camp at Cabanatuan. I stayed there until October the fifth. Conditions were a little better there. We had rice twice a day. We had some semblance of government. It wasn’t a picnic, but it was better than what we had been in. I was sent on a 2000 man detail to go to Japan and Manchuria. I was taken to Manila and we crawled aboard the Tottori Maru. She was an old ship that was built in the Port of Glasgow, Scotland in 1910 and was bought by the Japs for salvage. She had some holes at the waterline that you could have driven a jeep through. The pumps ran continuously. I was on that ship for thirty-one days. I thought it was the Hell ship. However after hearing some of the stories of the other Hell ships, I was on a floating palace. They packed us down in the hold as crowded as can be until we got out onto the high seas. Then the Captain opened the hatches and we had free run of the ship. I don't think any of the other ships had this privilege. A couple of days out a submarine threw two fish (torpedoes) at us. They were fired at extreme long range and they started to run on the surface. The Jap skipper saw them coming and turned the bow of the ship into them and both of them missed us. If he had not turned both of them would have hit. We had one heck of a typhoon and we went into the port of Macow a Portuguese city. We rode at anchor there and the guys started dying. Then one of the nicer things happened. The Jap Captain, who was a civilian, broke out the American flag out of his flag locker. We were allowed to use it in the burial at sea ceremony, like the US Navy tradition where you put the body on a board and cover them with the flag and then tip the board. The body would then slide into the water. We thought that was really a great gesture on the Captain's part. We were on that boat for thirty-one days. We finally docked in

Korea at the Port of Fusan. We call it Pusan now, I think.

We got off the boat and the Japs marched us for hours in sort of a victory

parade to show the Koreans what wonderful, big guys they had captured.

Some of us were almost naked. Then we got on a train and rode for

four days to Mukden Manchuria.

The first winter we were in a bunch of mud and board hovels that had been a Chinese training ground. The walls were boards with mud stuffed in-between them and the ceiling was the same. They were dug two and one half or three feet into the ground. It got down to 40 degrees below zero. We got one bucket of coal dust a day to warm those things. We never got the frost off of the floor. We did have four blankets. We would use one of them to cover our heads after we got into bed. When we woke up in the morning there would be frost around the hole over our mouth where our breath went. You would pretty much pry yourself out of the blankets. While I was in this camp, I had two toenails that were growing straight up. Our American surgeon decided he would do surgery. This surgery consisted of soaking my feet in a pan of cold water for a couple of hours in the cold barracks. Then he took a pair of pliers and just tore the nails out. It worked, they came back in straight. But, I took pneumonia. I got so bad they knew I was going to die. There was a place we called the zero ward. They would take one there just before death or just after they died. The body would be laid out with no heat. It would then freeze up solid. The temperature outside was so cold that we couldn’t dig graves so we had a morgue where the bodies were stacked up like chord wood. When the spring thaw came, there were some 250 bodies racked up in this one building were they had been collecting all winter long. I was placed in the zero ward. Anyhow, I went into a coma for about six days. I fooled them. Damn them. I didn’t die. I think there were two of us that didn’t die in the zero ward. I was lying there. I had been in a coma, and I heard this scratching noise. Scratch, scratch, scratch. We had rats two feet long. I thought my God the rats are going to eat me for sure. Then, I felt something pulling up on the board that was the bed. I thought, "Oh, here they come. "Then I felt something warm against my lip and I thought, "Oh my God, they are going to start on my face first. But it was my buddy who was suffering from spinal TB. He couldn’t walk. He had crawled in on his hands and knees with a cup of gruel twice a day and kept me alive. I made it out of there. A bunch of us were sent to Manchuria to install and operate a model 1156 machine, one of the most modern tool machines made in America. The Bill of Lading date on the boxes we unloaded was from New York, and San Francisco, October 1941, two months before the war started. These were sophisticated machines. I worked for the Navy after I got home, starting in 1956, for twenty years. I was making missile parts with machines that were more ancient than the ones we installed in that factory in Manchuria. We were sabotage experts. We sabotaged and we sabotaged. We had a British officer who was a mathematical genius. I would be making a bellcrank to duplicate the German index machine, one of the most sophisticated single spindle machine tools that existed in those days. The Japs had bought three of them and tore them down and copied them to make blueprints of them. We were to mass-produce this German index machine. When I was making a bellcrank, this British Officer would come over and say, "Now Jim, listen to me. Move every dimension to the plus side of the x and y axis, but do not get it out of tolerance. I want the piece to pass inspection." Well I would do this. He could see in his mind how these pieces worked together. He would go to Joe who was making the next piece. Same story. So what we did was to manufacture all these different pieces with all of the tolerance going in one direction. Now this can’t happen naturally. The errors will cancel each other if you just let nature take its course. But nature had the help of this officer. The Japs never could just assemble a machine and get it running. They did hand file and hand scrape some of them and they finally got 5 or 6 of them, at the end of two years, that that would run. When we installed these machines, we would do all kinds of sabotage. We had the biggest Grey planer I have ever seen. Two guys were required to ride the tool post to operate it. The bed was in, I don’t know how many, eight-foot sections. We would level and shim it. Then we would get the Jap to O.K. it. He would look at the level; he would bless it. We would send him to do something then we would pull shims out of one end and add shims to the other end. Stupid jerks never did figure it out. We had a shipment of electric motors come in. They were 1 ½ horse motors, which were pretty big. We had taught the honey dippers, the Chinese fertilizer merchants who brought in two wheel carts to dip out the latrines, how to put false bottoms in the crap box of their carts. We would give them these motors which they would stick in the false bottom and cover it with stuff. You know what. The Japs would probe it but they couldn’t tell it was one foot thick in places instead of two foot thick. Them Japs, honest now as God is my witness, would strip us naked to see if we had motors in our britches. We were unloading these freight cars which contained sausages and cheeses and foodstuff for the Japs. There was a bunch of abandoned foxholes along the side of the railroad tracks. We could flip a package of sausage or cheese down in these holes. The Japs thought there were snakes in the holes and they would never look in them. At night we would recover the packages. A civilian we called "Henry Ford" was a Jap who had been in charge of a Ford plant located in Mexico. He had returned to Japan to see his dad who was dying. However the Japs would not let him return to Mexico. He was sent to the factory to be a sabotage expert. He would go around with his little pad making notes all of the time. He called our section leader aside and said, “My wife and I are not eating very well. Figure some way to get us some of those sausages and cheeses, and I won’t find out about it. If not, I know all about it". He got out his little book out and started to tell about some of the things he knew. He ate sausage and cheese until the end of the war. But you know, that guy never found out a thing about sabotage. We had 150 prisoners that were eightballs and they put yellow tags on them. They sent this group to a hide factory. I was a semi eightball. I wasn’t bad enough to be an eightball. They sent me along with another 150 to a textile mill. By this time I learned if you were a little bit crazy the Japs, if they were of the right persuasion, thought that their gods looked after you. I convinced them that I was really crazy. There was a sergeant there that had lost a son and he wanted to have an Easter Service. The Japs wouldn’t let him have it. He said, “Brown would you please go over and see if you can get permission from that guy to have an Easter sunrise service." I said, "No I’m scared." He said, "Go ahead, I don’t think they will hurt you too much." So I went over and said, “Sir I would like to have a sunrise service." He stared at me and I stared at him. He reached into his desk and put a great big pair of paper shears next to me. I stared at him and he stared at me. He took his saber out and laid it on the desk in the scabbard with the handle towards me. I looked at him and he looked at me. He unsheathed his sword, stuck the point against his belly with the handle toward me across the table. I looked at him and he looked at me. He said, “Brown-san do you love me?” I said, “No I hate your black guts”. "Why don’t you take the sword and shove? It’s as sharp as a razor. I can't protect myself." I said, "What gained. One dead Jap, one dead American. Nothing gained". "Bachero bachero you are crazy, go go go have your service". Then is when I really got scared. I got over there and Arron said, “Brown since you got permission you will have to conduct the service”. I was a twenty-year-old kid. What did I know about holding a service? He said, "Well that’s what its going to have to be." I was pretty scared and when I went to bed, with no lights on, I lay there thinking. I thought and I thought. The next day I got up in front of these hundred and fifty Americans and all of these Jap officers and men and I looked out across there. I started out like this: Now I’m not a preacher

The meeting will now be in the charge of Sgt. Arron and I sat down. Sergeant Arron then ran the rest of the meeting. Bill Van Meter. May I ask one question? Just your point

of view. The difference between the situation of the lads that were

on Corregidor as opposed to those that were on Bataan.

On the trip home. I got on APA145, a beautiful new Attack Troop Carrier, the USS Colbert. We arrived at Okinawa and dropped the hook. The big blow, Typhoon, that hit Buckner Bay was coming our way and we were ordered out to sea to ride out the storm. We hit a 1500-pound mine and it blew the ship to hell. We lay dead in the water in 90-foot waves and 100 MPH winds. We were eventually towed into port. We were taken to the airport as they had decided to fly us to Manila.

There at the airport was the prettiest airplane I had ever seen, a C-54.

I had never seen anything like that before. As I was in line to get

on the plane, they shut the doors at three guys ahead of me, full.

They brought an old, war weary, oil dripping, wrinkle-skinned C-47 up there.

I guess now days you would call them a loadmaster, but then they were just

a sergeant in charge of the back end. I had some wings I had carved

out of brass.

I said “Yeah.”

Audience comment: What About Sections of Ten?.

Question from the audience. From your perspective. I

just received an e-mail that speculates that Franklin Roosevelt knew the

attack was coming.

Bill Van Meter: Jim, I can back that up a little bit. I have an uncle who was a Lieutenant in the artillery. He died on the Death March. My Aunt was sent back, in November, 1941. I remember my mother and my sister, my father and me talking with her. She said, “The war is coming. They have sent us all back. It’s got to be a few days away." This is my aunt, this was not the intelligence we had at that time. It’s not the politics that we had at the time because I checked that first. All this dawned on me later in life. Something was not kosher. And I can only say this in my opinion, and I’m biased. MacArthur's excuses for letting us sit on the ground and getting our whole damn Philippine fleet of airplanes wiped out. If we shot first the Japs would take revenge out on the Filipino's. So they had to hit us hard. He didn’t know that the Filipino's were Asian's and the Jap culture believed that if an Asian fought alongside of us they would be regarded as being of lower status than we were. Hell, they died at ten times the rate the Americans did. Anything else?

Question from the Audience: We had a gentleman two or three weeks ago who came into the Philippines about nineteen days before the war started for a B-24 squadron. He escaped into the woods before he got captured. He stayed free all the time that the Philippines were occupied. I wonder if there were many people that did that? There were a great number of guerrillas. It wasn’t the B-24, must have been the B-17 because we didn’t have any B-24s. (Questioner: The B-24’s never got there, just the crews came in. The planes never got there.) Could that have been the 27th Bomb Group? It could have been. Well it doesn’t matter. Several did escape and go into the jungle. I had one personal friend that was with a group of guerrillas. He got caught, some of the native in the huts turned him in. The Japs turned the whole village out and made them watch them behead him, that’s Betty’s brother. (Addressed to his wife in the audience) On the Death March I saw them blow the head off a little baby with a 30.06. I saw four Jap officers take five of six Filipino's across the road into a little ravine. I heard pop, pop, pop, pop. I heard a few screams; the Japs came back but the Filipino's never came back. They were all carrying American 45's (pistols) in their hands when they came back up from the hollow. Would you give your impressions of Generals MacArthur and Wainright?

There is another little human-interest story. Pauline and I were engaged five years, six months, and five days without a single date. The last five minutes I was in Indianapolis I popped the question. She said I thought you would never ask. I ordered her a diamond ring from the PX at Clark. Had it sent from New York to me. I said “yup that’s it” when I saw it. I put it on the China Clipper and sent it back to her in Indiana. I was missing in action and presumed dead for about two years. Pauline said, “ He is not dead. I would know". They put a gold star with my name on it up on the bulletin board there in the Town Square. When word came through that I was alive they told the guy that put the star up there to take it off. Jim’s coming home. He said “I’ll wait and let Jim take it down himself. When I got home, I took a putty knife, popped it off, and painted over it. Thank you guys. *Mr. Brown explains: eyesomdectomy: A surgical procedure where

the nerve between the eyes and the rectum is severed. This precludes

a shitty outlook on life.

|