THE

WESTERN GHATS

Geomorphology and climate of the Western

Ghats

The landscape of the Southern Indian tectonic

shield is believed to have evolved through a slow geomorphic process

(Radhakrishna 1993), which arose as a result of the movement of the

peninsular region into the rest of the Asian mainland and the resulting

geologic transformations. Volcanic activity over a period of 120 - 130

million years resulted in the formation of the present day Western

Ghats (Daniels 2001b). Along

with this, the peninsula also experienced an eastward tilt which

changed

the pattern of drainage. In many cases, like the river Sharavati and

Kali

in Uttara Kannada, the western faulting led to 'river capture' and

diversion of the easterly drainage to the west (Radhakrishna, 1991).

The Western

Ghats, which arose from these activities, presently forms a continuous

chain

of small to medium sized mountain ranges running along the western

coast

of Southern India. Recent work by Valdiya (2001) also indicates that

there

have been active neotectonic movements along the NNW-SSE leading to the

formation of faults and fractures. Among other geologic changes, this

has resulted in changes in the flow character of all rivers and streams

that flow to

the west and descend across the western margins of the Western Ghats.

There

are abrupt drops as water falls through gorges and cascades of rivers

flow

along the upper reaches of the Western Ghats. Rivers show anastomosing

patterns in the sinuosity of meandering in the upstream stretches. It

has also lead to the formation of stream ponds as the rivers flow

through these faults. For instance, in Uttara Kannada, we find the

ponding of the river Bedti

at the study sites of Ramanguli and Hoskambi.

The Western Ghats is a forested tract of relatively

smooth, but very old, mountain ranges bordering the South Western

coastline of India, starting from Central Maharashtra to the southern

tip of Kerala. The Western Ghats, along with another range of smaller

mountains - the Eastern Ghats, form a substantial percentage

(approximately 10%) of the forested area of the Indian Subcontinent.

It runs rather continuously north- south between 8

and 210 N latitudes. It covers a distance of approximately 1600 km-

being interrupted just once by the 30 km wide Palghat Gap at around 11

N. The narrow coastal strip that separates the hill chain from the

Arabian sea in the west varies in width from 30 to 60 km being the

narrowest between 14 and 15 N. Hills are generally of elevations

between 600 and 1000 m. However there are higher hills of 1000- 2000 m

between 8 and 13 N and

18- 19 N. Peaks over 2000 m are found only in the Nilgiris, Palanis and

Anaimalais. The Nilgiris and Palanis are spurs from the main hill

chain,

which extend the Western Ghats eastwards to approximately 78 E. Annual

rainfall on the Western Ghats averages 2500 mm. Rainfall as high as

7600

mm in localities such as Agumbe between 13 and 14 N is not uncommon.

The Western Ghats receives much of their rain from the southwest

monsoon.

Hence the wettest season generally lies between June and October. The

rainy

season in the southern latitude is however often prolonged locally due

to

pre-monsoon and winter showers. Thus the dry periods in parts of the

Western

Ghats south of 13 N are the shortest (2- 5 months) while in the north

it

varies from 5 to 8 months. Mean temperature ranges between 20 and 24 C.

However,

it frequently shoots beyond 30 C during April- May (summer) and

sometimes

falls to 0 C during winter in the higher hills. The Western Ghats

harbours

approximately 38 east flowing and 27 west flowing major rivers. The

west

flowing rivers originate in the Western Ghats and drain into the

Arabian

Sea while the East fowing ones merge into the three major river

systems-

Cauvery, Krishna or Godavari- before they drain into the Bat of Bengal.

Soil

The soil mainly consists of

the derivatives of the ancient metamorphic rocks in India, rich in iron

and manganese (Pascal 1988). There are exposed lateritic rocks along

the coastal hills

which appear black and are barren and mostly unfit for plant growth.

Some

granitic rocks are also present towards the southern parts of the

district. One distinct feature of this region is the formation of

limestone pannicles in the forests of Yanna. These are a unique feature

for the Western Ghats; they are, however, common in the forests of

South - East Asia.

Biogeography

An early attempt to classify the various

vegetation types of the Western Ghats was done by Champion in 1936 and

was later revised and enlarged by Champion and Seth in 1968.

Nagendra and Gadgil (1998) have identified 11 landscape elements (LSE)

or vegetation mosaics, including some anthropogenic kinds,

characteristic of the Western Ghats.

Because of its African origin, much of the flora

and fauna of the Western Ghats are shared with Africa, Madagascar and

also South America. Amongst fishes, some species of catfish (Clarias),

some Cyprinids (Puntius, Labeo, Rasbora and Barilius) as well as genera

like Notopterus and Mastacembelus are common to both India and Africa.

There are also similarities between the biodiversity of this region

with the East - Himalayan region. This is found to be true of some

species of fishes, mammals as well as birds (Hora 1949).

On a broader scale of the Western Ghats, studies on the biodiversity

of this region have shown that the overall species diversity here is

high. In fact, it has been counted as one of the world’s 18

biodiversity “hotspots”. There is also a high level of endemicity in a

number of taxa in this region - with nearly 2000 species of higher

plants, 87 species of amphibians, 89 species of reptiles, 15 species of

birds and 12 species of mammals (Daniels, 1997). There are around 218

species of primary and secondary freshwater fishes in the Western

Ghats. 53% of all fish species (116 species in 51 genera)

in the Western Ghats are endemic (Talwar and Jhingran 1991, Jayaram

1999,

Menon 1999, Daniels 2001a). Furthermore, freshwater fishes of the

Western Ghats have a high economic value – they are caught extensively

for food as well as ornamental purposes (in aquaria).

230 species of woody plants and 480 species of birds have been

recorded in the Uttara Kannada district. There is a distinct gradient

in species richness of plants in Uttara Kannada. The plant species

densities increase both from east to west as well as north to south.

This gradient of plant species richness coincides with the rainfall

gradient. A similar trend in bird species diversity is also observed,

but for birds, species diversity increases with decreasing rainfall,

with the maximum diversity being found in the intermediate rainfall

zone (Daniels 1989). Diversity patterns of reptiles and amphibians have

also been studied by Daniels (1991). The central Western Ghats are

rather

rich in butterfly species. While 249 species are known from the state

of

Goa, the Uttara Kannada district alone is known to harbour 300 species

(Gaonkar,

1996). Species richness data for fish and aquatic invertebrates have,

however,

not been documented in the recent times. A number of species have been

introduced into the waters of this region, most of which are in the

reservoir areas

of dams. Many have naturalised in the streams, ponds and tanks of the

region. Species like Oreochromis mossambics, Gambusia officinis,

Poecilia reticulata etc. are exotic species which are originally from

Africa and South America. Species like Rohu, Catla, Mrigal (carps which

are from the northern parts of India) have been introduced recently,

mostly for commercial purposes.

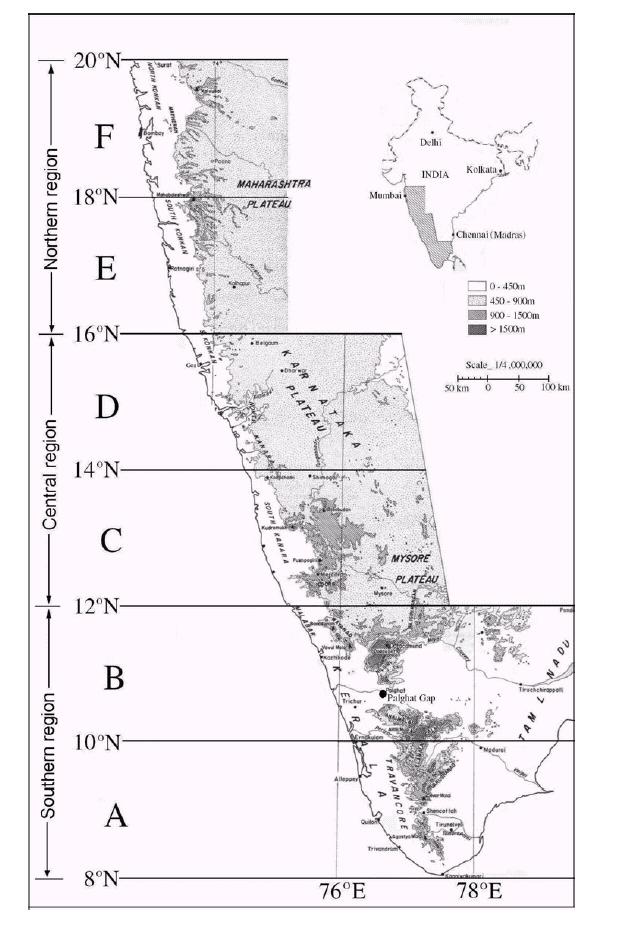

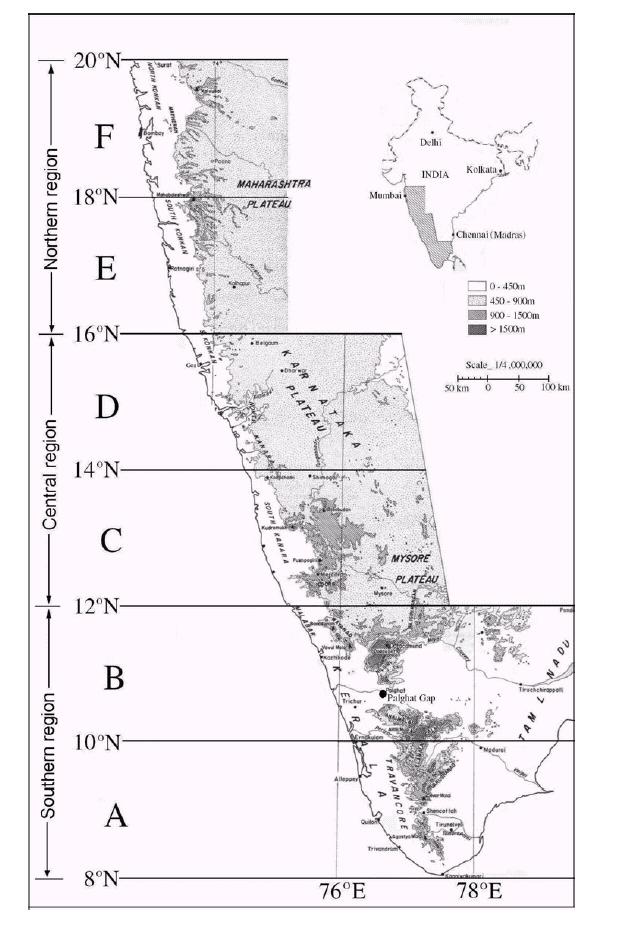

Figure 1: Map of Southern Western India showing latitudinal divisions.

Map adapted from Samant et al. (1996).

References:

Daniels, R J R (1989). A conservation strategy

for the birds of the Uttara Kannada district. PhD Thesis: Indian

Institute of Science, Bangalore. pp238.

Daniels, R J R (1991). The problem of conserving amphibians in the

Western Ghats, India. Curr. Sci., 60(11): 630-632.

Daniels, R. J. R. (1997). Taxonomic uncertainties and conservation

assessment of the Western Ghats. Curr. Sci. 73 ( 2): 169- 170.

Daniels, R. J. R. (2001a). Endemic fishes of the Western Ghats and the

Satpura Hypothesis. Curr. Sci., 81 (3):240-244.

Daniels, R. J. R. (2001b). A Report on the National

biodiversity Strategy and Action plan- the Western Ghats Ecoregion:

Submitted to the Ministry

of Environment and Forest, India. pp 129.

Gaonkar, H. (1996) Butterflies of Western Ghats, India including Sri

Lanka: a biodiversity assessment of a threatened mountain system.

Unpublished Report submitted to Centre for Ecological Sciences, IISc,

Bangalore.

Hora, S L (1949) Satpura Hypothesis of the Distribution of the Malayan

Fauna and Flora to Peninsular India. Proc. Nat. Inst. Sci. India,

15(8):309-314.

Nagendra, H and Gadgil, M (1998) Linking regional landscape scales for

assessing biodiversity: a case study from the Western Ghats. Curr.

Sci.,

75(3):264-271.

Pascal, J P (1988). Wet evergreen forests of the Western Ghats of

India. Pondicherry: Institut Francaise.

Radhakrishna, B P (1991) An excursion into the past - 'the

Deccan volcanic episode'. Curr. Sci., 61 (9&10):641-647.

Radhakrishna, B P (1993) Neogene uplift and geomorphic

rejuvenation of the Indian Peninsula. Curr. Sci., 64 (11&12)

:787-793.

Samant, J. S. Ajit Kumar, C.R., Thomas, R. and Biju, C. R.

(1996). Ecology of hill streams of the Western Ghats with special

reference to fish community. Annual (draft) submitted to Bombay Natural

History Society.

Valdiya, K. S. (2001). Tectonic resurgence of the Mysore

plateau and surrounding regions in cratonic Southern India. Curr. Sci.,

81 (8): 1068-1089).

Back to Main Page