The 1979

Moon Mission

Perhaps the most curious and inspiring event of the 1970's

was the Salvage 1 moon operation. In 1979, a private group set out to

salvage the equipment left behind by the Apollo moon missions.

Unfortunately, history seems to have forgotten the venture, perhaps

because its motivation seemed to be financial gain. However, junkman

Harry Broderick also had other more adventuresome desires driving him.

Broderick hired ex-NASA engineers to work in his junkyard with the idea

of eventually putting such a spaceflight together.

Click

for larger version.

|

|

These engineers decided simplicity was the only way they would be

successful. Whereas NASA space vehicles had redundancy upon redundancy,

the Salvage crew settled for an 85% to 90% safety factor. They were

wanting something that was quick and cheap since they didn't have the

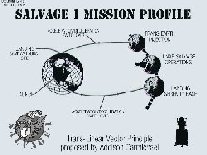

luxury of tapping the resources of an entire country. The Salvage 1

mission to the moon was successful because of two main things: the

flight plan and the fuel.

Click

for larger verson.

|

Click

for larger version. |

The flight plan was based on an idea called the Trans-Linear Vector

Principle, as put forth by ex-astronaut Addison Carmichael. Under this

principle, the Vulture rocket lifted off for the moon under slow but

constant acceleration. Although the initial velocity seemed much too

slow to ever reach the moon, the steady acceleration soon brought the

Vulture to great speeds once in space. Acceleration continued until

they reached the halfway point between the Earth and Moon, at which

time the ship began to decelerate ending in a smooth touchdown on the

lunar surface. Total time to reach the moon was a mere 24 hours

compared to three days for the Apollo missions. The trip back home

followed the same procedure. The advantages of the Trans-Linear Vector

Principle were many-fold:

- Two days round trip to the moon and back.

- A single stage rocket was all that was needed

for the flight, reducing complexity.

- No mid-flight orbiting of either the Earth or

the moon. It was a direct ascent and descent flight.

- No re-entry heating since the trip through the

atmosphere was a slow, gentle descent.

- No weightlessness since the ship was always in

a state of acceleration or deceleration.

Click image for

larger version. |

The disadvantage was that the fuel had to be more

powerful and therefore more dangerous than conventional rocket fuels.

This fuel was the highly unstable mono-hydrazine. Mono-hydrazine

combusted explosively when its temperature rose too high. Melanie

Slozar worked on this problem and was able to raise the critical

temperature point up to 150 degrees F. The ship's tank was surrounded

by coolant loops to keep the temperatures within constraints. The

Vulture had the capacity to carry 1000 gallons of Mono-Hydrazine, but

only 800 gallons were needed for the round trip to the moon. Guidance

was provided by hacking into an aerospace company's super-computer. On

the return home, due to some unforseen problems, NASA allowed the use

of their tracking system. Had they tried this flight today, no doubt a

laptop computer would have been sufficient!

|

|

Skip Carmichael and Melanie Slozar piloted the

Vulture on its mission, landing at Serenity Base on January 20, 1979.

After the ship was loaded up with old Apollo equipment (lunar rover,

etc.), they began the trip home. There were problems encountered during

the return flight, namely the loss of their guidance link and a coolant

leak, but the mission was carried out successfully much to the delight

and admiration of the world. Leaders including President Jimmy Carter

sent their congratulations to the Salvage 1 team.

In these days when the governments of the world rarely look beyond low

Earth orbit, perhaps someday soon another bold team of individuals will

take on the adventure of flying to the moon.

The Salvage team after the mission

|

|