THE HOMESTEAD OF JOHN CHAFE (c.1685-1759) IN PETTY HARBOUR, NEWFOUNDLAND

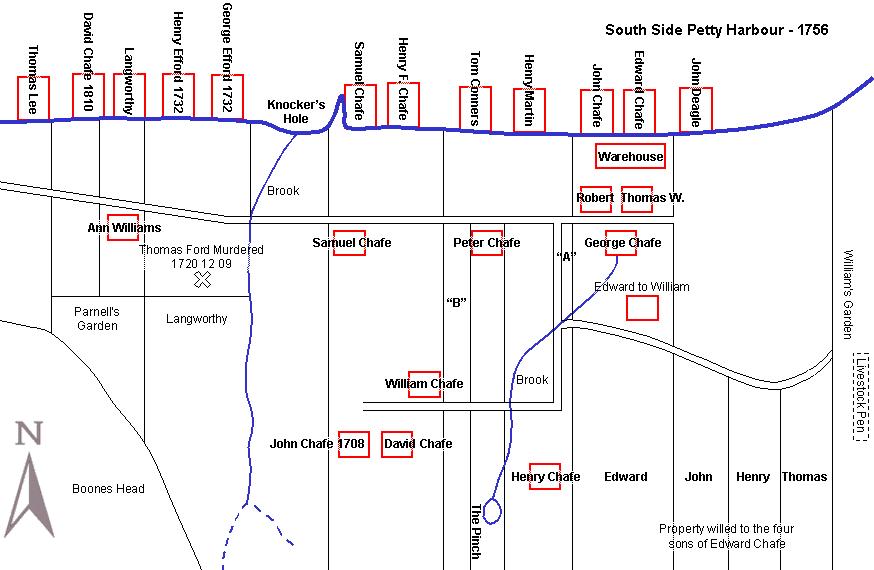

by Ray Leaman with dates and notes in italics by webmasterThe four Chafe Brothers were Samuel, William, Henry, Edward all born in Newfoundland and listed in the 1794 census in that order. The homes of those four are found on early photographs. As they and the succeeding generations houses were identified it became that each had a large piece of land with their children gathered around them. Samuel had no children but his house was located. An extensive search was made of the Colonial Office files, the Registry of Deeds, verbal information and private papers. The Colonial files shows the oldest house was a sod covered rock wall basement said to belong to John Chafe, the father of the above four. The transfer of property 1724, the Registry of Deeds shows the transfer of property in 1735 and private papers show the sale of Henry Martin's land in 1756.

The western boundary of what was known as William's garden is clearly marked by two small properties given to his grand children. One of whom was my grandfather. The larger part went to William's (b.1803) son Robert (b.1832). It was well known in my time that Robert's son Josiah (1867-1949) held possession.

William's grandfather was Edward (Henry? 1725-1801) who was in the 1794 census. To locate his western boundary, it is necessary to refer to his brother Henry's land which was next to his. William John Leamnan about 1940 gave up fishing with his father and brother. With his own crew a boat and three cod traps, he became a very successful fisherman. He acquired the fishing rooms of Robert Chafe. A parcel of Henry Chafe's land identified by an "A". On the death of James Chafe, he acquired a third property identified by a 'B". William John hired a lawyer to take care of the sale and registry. He was told that James Chafe's land was purchased from Henry Chafe's estate by James' great-great-grandfather John Chafe. By referring to William John Leaman's land, the lower part of Henry Chafe's land can be established with great accuracy. Sadly, to gain title, none of the rich background was used.

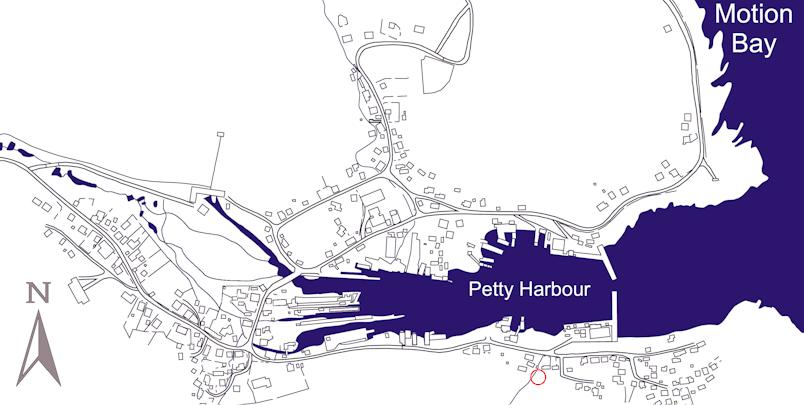

James Chafe's great-great-grand father, John Chafe also held the Henry Francis Tree Rooms from 31 Oct 1805. James fished from those rooms up to a short time before his death. The photo on the right, shows the possible location of Chafe homes circled in red. John Chafe's house could be the house in the background on the right. This photo is not in Leaman's document.

Knockers Hole was the watering place for the four fishing vessels anchored at Admiral's Room on the opposite side of the harbour. By 1770 vessels from Devonshire no longer came to fish and Henry Daspher built a fishing room there. Henry married Ann Chafe 13 May 1800 the daughter of Henry. On the 5 Dec 1814 Henry sold Knockers Hole to his father-in-law's brother William Chafe and took his wife and their three children back to Devonshire.

The Ford property was occupied by Jacob Chafe of Petty Harbour Bait Skiff fame about 1827. William and Ann Williams occupied the Langworthy rooms next to him. Her will of 184 states that Jacob Chafe lay on the East boundary, to the south lay Pamell's Gaden, on the West lay Codner's Room, on the North was the saltwater. In 1810 David Chafe owned Codner's Room. In 1817 Sam Codner called his loan of £50 and David's possessions were auctioned on Newman's wharf in St. John's. Dartmouth merchants Daniel Codner and John Jennings ran a business from this site for the next forty years.

The nearby land where Thomas Ford was murdered was "held up" for a long time and eventually bought by Jacob Chafe (b.1842).

Webmasters Note: From a site visit in August 2004, it is likely the John Chafe's house was more to the west as it was told that those in the house could reach out of their window and pull water from the brook.

John Chafe's house was likely rebuilt a century years ago. A house that was located on this site was still standing in the late 1970's. It is locally believed that the house was approximately 100 years old. There is no house located on this site today.

(Town layout showing homestead location near the brook leading to Knocker's Hole - above layout not in Leaman's document)

A native of Boston, Massachusetts, William Keen went to Newfoundland in 1704 to act as agent for New England merchants involved in the supply trade. After 1713 he commenced trading on his own account. As one of the first men to exploit the salmon fishery along the old French shore north of Cape Bonavista, he was a powerful force in the extension of English settlement into that area. By 1740 he was carrying on a considerable trade to New England, Britain, and southern Europe, exchanging fish and possibly furs, for provisions and manufactured goods. At the time of his death he possessed extensive property in St Johnís, Harbour Grace, and Greenspond.

Keen is remembered, however, not for commercial acumen, but as a key figure in the development of justice in Newfoundland. By 1699 the British government had decided to allow limited settlement in Newfoundland, without encouraging its expansion. A rudimentary legal system was created which vested all power in the "fishing Admirals," who migrated annually to Newfoundland during the fishing season, with a power of appeal to the equally transitory naval convoy commanders who escorted the fishing fleet from Europe. The theory behind this system was that fixed government would inevitably encourage an increase in fixed settlement and destroy the migratory "nursery of seamen" so vital to Englandís Royal Navy. This rudimentary justice was probably inefficient and corrupt even when the fishing admirals were visiting Newfoundland, but when convoy and fishing ships left the island at the end of the fishing season, there was no established judiciary for the winter inhabitants. Under the system, all men accused of capital crimes were to be transported, with two witnesses, to England for trial. Not surprisingly, few men were ever accused of capital crime, and from 1715 onwards the "respectable" portion of the Newfoundland residents began to agitate for a judicial system that would protect their lives and property from lawless servants and "masterless men" during the winter.

Many naval convoy commanders, distrusting the fishing admirals and detesting lawlessness, sympathized with the need for a more permanent judicial system, and in 1718 one of them, Commodore Thomas Scott, recommended that "winter justices" be appointed annually to serve until the fleet returned the following year. His first suggestion for magistrate was William Keen who "tho a native of New England seem[s] concerned for the prosperity of the fishery . . . and has spirit enough." The Board of Trade refused to change their policy but in 1720 the murder of a prominent planter, Thomas Ford, created a new crisis. Keen apprehended the suspects, and sent them with witnesses to England in one of his ships, at his own expense, but pointed out that the cost discouraged "respectable" inhabitants from apprehending criminals. A petition of the planters of Petty Harbour asked that winter justices be appointed and that "encouragement be given to such useful and able men as Mr. Keen." The Board of Trade again refused to take action. In the winter of 1723-24 the planters of St Johnís, in some desperation, formed themselves, for their mutual protection, into a Lockian "society" which, though it soon collapsed, once more demonstrated to the authorities that a growing population would inevitably require a formal year-round legal system. Keen sent a capital criminal for trial in England again in 1728, and noted that malcontents, knowing their chances of conviction were remote, were growing daily more insolent and the "sober inhabitants" would soon be forced to leave the country.

Keenís attempts were now greatly aided by the reports and arguments of Lord Vere Beauclerk, the convoy commander in 1728, who was distressed by lawlessness in St Johnís and by the inefficiency of the fishing admirals. Above all he felt that only permanent civilian magistrates could control the depredations committed by Samuel Gledhill, garrison commander at Placentia. When he left Newfoundland in the fall, Beauclerk appointed Keen to report on any lawless occurrences. Keen duly wrote several letters urging that magistrates be appointed, and offering himself as a candidate. In 1729 the English government admitted the need for justice by issuing an order in council which turned the naval convoy commander into a "governor" (though still migratory) and by sanctioning the establishment of "winter" justices of the peace who were to act only when the fishing admirals were absent and hear only petty criminal offences. William Keen was one of the first magistrates appointed, and he retained the position almost annually until his death.

In fact the first "governor," Captain Henry Osborn*, encouraged the magistrates to hear cases on a year-round basis, and also to settle civil disputes. Until 1732 there were many conflicts between the new justices and the fishing admirals. The latter had legality on their side, but the magistrates had the active support of the governors, such as George Clinton, and the passive acquiescence of the English authorities. By 1735 the migratory merchants, some of whom were staying on through the winter, either themselves became the magistrates, or controlled those who were appointed, and they ceased to oppose the innovation. Keen, as the leader of those who had urged a magistracy, now became the leading figure in Newfoundland. Successive governors, appointed only for a year or two and spending only a few months on the island, relied heavily upon him for advice and assistance, and Keen was able to monopolize whatever meagre official positions were created during his lifetime, becoming commissary of the vice-admiralty court in 1736, naval officer for St Johnís in 1742, and Newfoundland prize officer in 1744. He was often criticized for his conduct as a magistrate, as in 1753 when Christopher Aldridge Jr., commander of the St Johnís garrison, charged that Keen had jailed some of his soldiers without trial. His mercantile contemporaries characterized him as a man who used his official influence for private advancement and gain and was "careful to keep in with the Commodores." Though there is little doubt that he took whatever advantages came from his position, it is difficult to see that any man of this age would have acted differently.

The order in council of 1729 had created a resident judiciary in Newfoundland, but the trial of capital crimes was still reserved for English courts. During the 1730s successive governors, such as Fitzroy Henry Lee, urged that a court of oyer and terminer be established in Newfoundland, and in 1737 the Board of Trade almost decided to initiate one. No action was taken, however, and the war of 1740-48 forced both naval governors and English authorities to turn their attention elsewhere. In 1750 another order in council provided that the justices of the peace in St Johnís might act as commissioners of oyer and terminer in all cases except treason, although they could only sit during the presence of the governor. William Keen was the first commissioner to be appointed.

Ironically one of the first cases of murder to be tried by the new court was that of Keen himself, committed by soldiers and fishermen in the course of robbery in September 1754. Four of the nine persons implicated in the murder were subsequently hanged; the remainder were reprieved. The accused were all Irish, and fear surged through the English populace, who took the murder as an indication of widespread looting and violence to come. The Irish, for their part had grown justifiably incensed by their inferior treatment, especially in the intolerance to their religion. Keenís son, William, inherited his fatherís business and his position as a magistrate, but was eclipsed in political influence by another New England immigrant, Michael Gill. By 1760 he had moved to Teignmouth, Devonshire, England, and the centre of his Newfoundland commerce shifted north to Greenspond. The Keen plantations in St Johnís and Harbour Grace remained, however, in the familyís possession until 1839.

CORRESPONDANCE BY JOHN CHAFE - 1721

Source: CO 194/7, page 21 dated April 1, 1721 and sent as a result of the Thomas Ford Murder (copy of document in possession of the webmaster)

To the Right Honourable the Lords Commerce for Trade and Plantations

The Petition of the Inhabitants of Petty Harbour in Newfoundland

Most Humbly Sheweth

That your poor petitioners in the plantations under the Immediate Care of your Lord labour under severe difficulty for Want of the administration of Justice Amongst us, and in the winter Season especially are in danger of our lives from our Servants whose debauched Principals lead them to Commit wilfull and open murder upon their masters, an instance of which has lately happened upon this place.

Your Lords will be pleased to take notice that Mr. William Keen of his own free will and at his own Cash and Charge now sends the mallifactors with evidence for their Conviction and we humbly pray that justice may be done to the offenders and encouragement given such Usefull and able men as Mr. Keen has approved himself for sixteen years past in our world of Troubles. Your Poor Petitioners humbly pray that such power may be granted to Reside at St. Johns as may be need free for punishing offenders without which will be Impossible for your poor petitioners to live in safety.

Your Petitioners only beg justice in common with the rest of His majesty Loyal subjects and Your Petitioners as in Duty Bound shall ever Pray.

Edward Andrews

Samuell Angell

John Chafe

Henry Warn

John Churchwood

Arthur Liscum

Edward Salisbury

Richard Jackson

Azarias Cundett