Very few fountains were known to exist prior to the mid 16th century,

due to the lack of running water that during the Middle Ages

for about 1,000 years represented one of Rome's main problems.

The only aqueduct still partly working was the Aqua Virgo, whose springs

were located east of Rome, although it reached the city from the

north, due to the duct's winding course. The water flow was much lower than in

ancient roman times, as the original channels were damaged, and new springs

were used, closer to Rome, yet less abundant and less clean (see also

Aqueducts,

page 6).

The aqueduct ended in a central spot,

below the Quirinal Hill, by a three-way junction (in Latin trivium),

mentioned in old chronicles as Treio, whence the other name "Trevi water"

still in use today, although some maintain that this name derived from the

location of the original springs, a place once called Trebium.

The water gushed out from three individual outputs, each of which had a plain

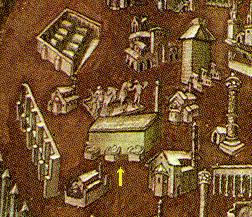

basin, without any particular decoration. Visual records of this early fountain

are very scarce; one of them is a painted medallion by Taddeo di Bartolo

(c.1410), featuring a simplified map of Rome's monuments and ancient ruins.

Few would recognize in this small structure the

nucleus of what is today one of Rome's most renowned landmarks, the Fountain of

Trevi, described in a further page. |

the three original basins (arrow) |

the fountain, following Nicholas V's alterations |

Only at the end of the Middle Ages pope Nicholas V improved

its shape by replacing the three basins with a long rectangular one, also

adding a large marble plaque, whose inscription read: pope Nicholas V,

after decorating the city with important monuments, in 1453 restored the

Aqua Virgo from its old decay.

This look remained basically unchanged for over two centuries.

In the city's western outskirts stood St.Peter's basilica.

The Aqua Traiana, which in ancient times had served this part of Rome,

had been restored in the late 8th century, but it had only worked again for

200 years. |

The Vatican could still rely on a small amount of water, thanks to a few

very early ducts, that had been originally dug by the time of pope Damasus (366-84);

they drew water from minor springs, that had been found somewhere below the

nearby Janiculum and Vatican hills.

These ducts supplied the main fountain

in St.Peter's courtyard (see part I page 2),

and probably also two smaller ones, located not very far from the basilica.

They had remained in good condition thanks to maintainance works occasionally carried out,

especially under two popes: the afore-mentioned Nicholas V (1447-55) and Julius II (1503-13).

|

the old fountain facing St.Peter's,

featured in mid 16th century drawings |

One of the two working fountains stood in the open place in front of the basilica,

today's St.Peter's Square; a few old drawings show in detail its elegant shape,

consisting of two round basins of different size, collecting the water that gushed

from the uppermost element, decorated with four small figures, and resting

on a circular base of three steps. |

the old St.Peter's basilica and the fountain (arrow),

in the mid 1500s |

According to old documents, it was built around 1490. A decade later, probably

among other works for the Jubilee year 1500, pope Alexander VI had nozzles

shaped as bull's heads added to the top basin, but the fountain's shape remained

basically the same.

An even older one is featured by the church of Santa Maria in Trastevere,

in a map dated 1472 which shows no fountain by St.Peter's yet. Being similar to

the previous one, it is likely that it may have acted as a source of inspiration

for the one described above.

(left) S.Maria in Trastevere in a map of 1472, and (right) enlargement

of the fountain; in this map no fountain stood yet before St.Peter's

|

|

Santa Maria's church stands on the same side of the

Tiber as St.Peter's, about 1.5 Km or 1 mile further south,

thus the fountain was almost certainly connected to the same early ducts that drew

water from the Janiculum's springs.

In the map its lower basin appears square in shape, but this may have

been a simplification due to the miniature size of the actual drawing:

in fact, many medieval baptismal fonts and wells

were octagonal, and this shape was also maintained by several fountains of

the 16th century. Furthermore, in 16th century maps it seems to have

eight sides. |

Built around the mid 1400s, some scholars suspect that it may

have replaced an even older one, whose dating could likely extend far back

to the ancient roman days. In fact, the Aqua Alsietina, i.e. the aqueduct

that emperor Octavianus had built for his naval stadium in Trastevere (see Curious and Unusual,

page 4),

very close to this spot, may have easily supplied also a local fountain,

although the water it drew was non-drinkable.

But the Aqua Alsietina had been

abandoned during the late imperial age; sometime around the 4th century, the surface of the

lake from which the water was drawn (see Aqueducts, part III page 3) had dropped below the level of the aqueduct's tunnel. Therefore, in the 15th century Trastevere's fountain could only work with the little water drawn from the Janiculum springs, whose pressure was also rather low.

For this reason, around year 1500, the uppermost basin was removed, so to lower

the height of the nozzle. We see the

result in 16th century maps (more detailed visual sources are not available).

Scholar Cesare D'Onofrio maintains that wolf's heads were also added to the

remaining round basin, referring to cardinal Lopez, who was in charge for

Santa Maria in Trastevere and its surroundings, and whose surname was

reminiscent of the Latin word lupus ("wolf"). |

the fountain without its top basin |

During the following centuries, both the fountain in front of St.Peter's

and the one in Trastevere underwent further changes.

The former, deeply altered, still exists, while the latter, also altered,

was definitively replaced in 1873. Since their evolution

was affected by the reopening of the ancient Aqua Traiana aqueduct (1612),

they will be dealt with again in the pages yet to be published.

Nevertheless, their classic shapes stirred the architects' interest

throughout the Renaissance, and inspired

many fountains built up to the turn of the 17th century.

FOUNTAIN-MAKING AND FOUNTAIN-MAKERS

During the Renaissance the making of fountains became a new and rather

frequently requested activity. Owners of mansions and villas,

city administrators, the popes, anybody who could afford fountains

wanted them. Special skills were developed in the field of hydraulics,

and a few architects became specialized in blending art and science,

obtaining results in which beauty and utility were cleverly combined.

The making of a fountain was a complex team work, that involved a certain

number of artists and craftsmen.

Usually the architect was in charge for the final result;

he was the one who designed the fountain, agreed its shape and costs

with the client, but also kept in mind the water's pressure and flow,

the hight of the chosen spot, the distance from the aqueduct's main course,

and other technical parameters.

Very often a different artist designed in full detail the single statues, groups and

reliefs needed for the project (seldom the architect did this himself);

his artistic level was sometimes rather high, as in the case of the fountains built

by Giacomo della Porta, whose preparatory drawings were made by the professional

painter Jacopino del Conte. |

|

marbles and stones more often used

1 - travertine

2 - white marble

3 - portasanta marble |

|

4 - African grey marble

5 - basalt

6 - granite |

|

|

The drawings were then handed to one or more skilled stone-masons, who actually

carved the statues, reliefs, etc. In a few cases also this duty was carried out by distinguished

artists, as in the case of the Fountain of the Tortoises, whose bronze groups

are by sculptor Taddeo Landini.

But with very few exceptions, the only name remembered

(or blamed, in a few cases) for the fountain was, and still is, the architect's

own.

The type or types of marble and other stones used in the

making of a fountain depended both on their cost and on their availability;

if one quality was reputed too expensive, or a block suitable for being carved

could not be found, often a different marble was agreed.

The main qualities used were the whitish travertine (the cheapest one,

thus the kind more extensively used), the more expensive white marble,

the reddish portasanta marble (from the island of Chios, Greece), and the African grey marble.

Other stones, such as basalt and granite, are sometimes found

in the shape of statues and basins from ancient Rome or

Egypt, unearthed and recycled in various ways during the Renaissance.

Also bronze was used in a few cases, for statues and other additional elements.

Curiously, most of the marble used for the making of Rome's fountains

did not come from quarries, as one could expect; it consisted of blocks

taken from the remains of many ancient establishments (baths, fora, etc.) all over Rome,

that were cut and reshaped to fit the new project's needs. Up to the 17th century, many of today's most important

archaeological sites were literally plundered by the popes and their artists.

|

GIACOMO DELLA PORTA (1533 - 1602)

Born in Genoa, della Porta was one of the most distinguished

architects and sculptors of the 16th century. In Rome he worked in an

incredible number of churches and buildings, often taking over unfinished

projects by Vignola (his main teacher) and Michelangelo, and sometimes

modifying their original designs.

During the last three decades of the 16th century he supervised the works

for the making of the new St.Peter's basilica, whose dome he completed.

After the reopening of the first aqueduct, he became the first official

fountain-maker, and certainly the most prolific one Rome ever had:

he is credited for fourteen main fountains, which he built in

piazza del Popolo, piazza Colonna, piazza Navona (two), piazza della Rotonda,

piazza San Marco, Campo de' Fiori, piazza Mattei, piazza Madonna dei Monti,

piazza Giudia, piazza Montanara, piazza Campitelli, and two of the

fountains on the Capitolium hill. Also the grotesque mask for the

drinking trough in Campo Vaccino was carved by this architect (see part II,

page 1), as well as a small semipublic

fountain, no longer existing.

Della Porta is often accused by modern critics of

having followed a somewhat monotonous scheme, which always includes one or two

small basins (1), supported by a baluster (2), in the middle of a larger

lower basin (3), usually with a complex geometric shape, resting on three or

four steps (4) so to compensate

any uneveness or slope of the ground.

This scheme was clearly inspired by the late medieval fountains previously

mentioned. |

typical scheme of della Porta's fountains |

DOMENICO AND GIOVANNI FONTANA (1543-1607) (1540-1614)

Domenico was the most outstanding member of a whole family of architects from

Ticino region, now in Switzerland. Still young, he came to Rome to work in the villa

of cardinal Peretti, before he was elected pope (Sixtus V). Later on he worked on

St.Peter's central lantern and naves, replacing della Porta as a supervisor,

together with C.Maderno.

the no longer existing fountain by G. Fontana |

|

According to Sixtus V's busy town-planning projects,

D.Fontana opened new main streets that cut straight through the old districts;

he also moved four ancient obelisks to their

new location, and built the new Lateran Palace.

The only fountain still standing that was entirely drawn by this architect is

that of Moses, i.e. the main output of the Aqua Felix aqueduct.

Fontana's elder brother Giovanni, instead, is credited for having supervised the

making of the Aqua Felix aqueduct and for having cooperated with Flaminio Ponzio for the making of the huge Acqua Paola fountain

on the Janiculum hill. He also cooperated with Vasanzio for the fountain by Sisto Bridge.

A smaller yet elaborate work entirely by G.Fontana (left), on the same hill, was removed in the 19th century,

probably because badly damaged during a battle. |

Other members of the family who worked in Rome were Carlo (Domenico's nephew,

1638-1714), Francesco (Carlo's son, 1668-1708) and Mauro (Francesco's son, 1701-67).

Carlo added a basin to the Acqua Paola fountain, and

slightly altered the old one before Santa Maria in Trastevere;

he is also often credited for the second fountain in St. Peter's square,

although this is controversial, as some reliable scholars maintain that

Bernini was the actual maker.

GIOVANNI VASANZIO (JAN VAN SANTEN, or VAN ZANTEN 1550 - 1621)

A Dutch architect, wood-carver and engraver from Utrecht, whose name was Italianized when he came to Rome. Here he studied with Flaminio Ponzio, with whom later on he also cooperated. Although in the early 1600s Paul V appointed him "fountain architect", i.e. the official supervisor of fountain-making in Rome, he is mainly remembered for having built the large one by Sisto Bridge, and for having drawn a few minor ones for the Vatican grounds.

CARLO MADERNO (1556 - 1629)

One more member of the Fontana clan: he was Domenico's nephew.

Maderno began his carreer as a stone-mason. When his uncle

called him to Rome, he distinguished himself with the making of Santa Susanna's church.

In charge for St.Peter's works together with Domenico Fontana, he is credited for

the enormous façade of the basilica. He also took part to the making of several among Rome's palaces

and mansions, among which the Quirinal Palace and the famous "harpsichord"

of the Borghese family (see

The 22 Rioni,

Rione IV - Campo Marzio).

He is also remembered as the author of the first of the two fountains in

St.Peter's square, into which he turned the late medieval one previously described

in this page. Maderno also built the fountain in front of Santa Maria Maggiore,

and the one for piazza Scossacavalli (moved to the bottom of corso Rinascimento

when this square disappeared).

Remarkably, also one of Carlo Maderno's nephews was to become a famous architect in Rome, although he only built a small wall fountain in the Vatican: Francesco Castelli, who later on changed name in Francesco Borromini (1599-1667). |

|

GIROLAMO RAINALDI (1570 - 1655)

Another dinasty of architects was the Rainaldi family. After having

been taught by his own father Adriano, Girolamo came to Rome, where he met

both Domenico Fontana and Giacomo della Porta; due to their influence,

Rainaldi's architectural schemes mainly remained those of the

late Renaissance, despite with the turn of the 17th century, in Rome

the Baroque age had already begun.

His most famous building is Palazzo Pamhilj, but among other works

he is also remembered for the curious bird cage built for Villa Borghese.

His only fountains are the couple of ancient tubs that face Palazzo

Farnese.

His son Carlo (1611-1691) at first cooperated with Girolamo in the making of

the Palazzo Nuovo, on the Capitolium, then worked alone

on the façade of Sant'Andrea della Valle, drew the project for

the twin churches of piazza del Popolo, but he did not build

any fountain.

GIANLORENZO BERNINI (1598 - 1680)

Architect, sculptor, painter, playwright and scene-painter, master of Rome's

Baroque age.

|

His teacher was

his own father Pietro (1562-1629), author of the Barcaccia fountain.

After his early works for cardinal Borghese, he became the artist that

pope Urban VIII preferred among the many available in Rome;

for this pope Bernini built the famous

canopy in St.Peter's, and created the colonnade that surrounds the vast square

in front of the basilica.

He is also remembered for several sculptures ( Extasy of St.Theresa,

and the so-called Minerva's Chick,

among others). Despite Urban's successor, Innocent X,

preferred to him Francesco Borromini, Bernini's production continued

throughout the century, as he outlived three more popes.

As a fountain-maker, he is credited for masterpieces such as the Triton in

piazza Barberini, and the great Fountain of the Rivers in the center of piazza Navona,

the square in which he also improved one of the two preexisting works

by della Porta. Some claim his authorship for the second fountain in St.Peter's square,

but this issue is debated. |

NICOLA (or NICCOLÒ) SALVI (1697 - 1751)

A pupil of architect Antonio Canevari, he would have remained an obscure

personage, had his only masterpiece not become one of Rome's very symbols: the Fountain of Trevi.

Enough for his name to enter the hall of fame of the city's most famous

fountain-makers.

other pages in part III (clickable)