Esperanto - la internacia lingvo por la tuta mondo

Esperanto seems to me beyond doubt, taken all round, superior to all present competitors, but its chief claim to support seems to me to rest on the fact that it has already the premier place, has won the widest measure of practical acceptance, and developed the most advanced organisation. It is in fact in the position of an orthodox church facing not only unbelievers but schismatics and heretics -- a situation that was foretold by the philologist. But granted a certain necessary degree of simplicity, internationality, and (I would add) individuality and euphony -- which Esperanto certainly reaches and passes -- it seems to me obvious that much the most important problem to be solved by a would-be international language is universal propagation. An inferior instrument that has a chance of achieving this is worth a hundred theoritically more perfect. There is no finality in linguistic invention and taste. Nicety of invention in detail is of comparatively little importance, beyond the necessary minimum; and theorists and inventors (whose band I should delight to join) are simply retarders of the movement, if they are willing tosacrifice unanimity to "improvement".

Actually it seems to me, too, that technical improvement of the machinery, either aiming at greater simplicity and perspicuity of structure, or at greater internationality, or what not, tends (to judge by recent examples) to destroy the "humane" or aesthetic aspect of the invented idiom. This apparently unpractical aspect appears to be largely overlooked by theorists; though I imagine it is not really unpractical, and will have ultimately great influence on the prime matter of universal acceptance. N**, for instance, is ingenious, and easier than Esperanto, but hideous -- "factory product" is written all over it, or rather, "made of spare parts" -- and it has no gleam of the individuality, coherence and beauty, which appear in the great natural idioms, and which do appear to a considerable degree (probably as high a degree as is possible in an artificial idiom) in Esperanto -- a proof of the genius of the original author...

My advice to all who have the time or inclination to concern themselves with the international langauage movement would be: "Back Esperanto loyally."

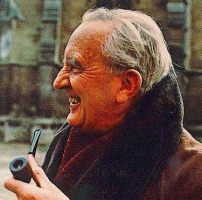

J.R.R. Tolkien

(from The British Esperantist, 1932)

(Note: N** probably refers to Novial)

Esperanto sxajnas al mi sendube, en sia tutajxo, supera al cxiuj aktualaj konkurajxoj, sed gxia cxefa pretendo al subteno laux mia opinio estas la fakto, ke gxi jam okupas la unuan lokon, havigis al si la plej largxan kvanton da praktika akcepto kaj evoluigis la plej altgradan organizadon. Gxi fakte similas ortodoksan eklezion, kiu frontas ne nur al nekredantoj, sed ankaux al skismemuloj kaj herezuloj -- situacio antauxvidita de filologoj. Sed kondicxe je ia necesa grado de simpleco, internacieco, kaj (mi volas aldoni) individueco kaj euxfonio, -- kiun Esperanto nepre atingas kaj superas -- sxajnas al mi memevidente, ke la plej elstare grava problemo solvenda de aspiranta internacia lingvo estas universala diskonigo. Ilo, kiu estas malpli perfekta, tamen havas eblecon realigi tion, pli valoras ol cent, kiuj teorie pli perfektaj. Ne ekzistas definitivo en lingvaj inventado kaj gusto. Fajna inventemo pri detaloj estas kompare malgrava, post la necesa minimumo; kaj teoriemuloj kaj inventemuloj (al kies trupo mi volonte aligxus) simple malhelpas la movadon, se ili pretas oferi unuanimecon pro "plibonigado".

Efektive sxajnas al mi ankaux, ke tehxnika plibonigo de la strukturo, cxu cele al plia simpleco kaj klareco, cxu al pli largxa internacieco, aux al kio ajn, emas detrui la "homecan" aux estetikan aspekton de la inventita idiomo. Tiun supozeble nepraktikan aspekton sxajnas grandparte malatentita de teoriemuloj; kvankam mi imagas, ke gxi ne estas vere nepraktika, kaj finfine profunde influos la cxefaferon de universala akceptigxo. Ekzemple N** estas ingxenia kaj pli facila ol Esperanto, sed malbelega -- "uzina produktajxo" estas klare surskribita. Aux prefere "kreita per rezervaj partoj" -- kaj tute mankas al gxi tiu ekbrilo de individueco, kohereco kaj belo, kiu aperas en la grandaj naturaj idiomoj, kaj kiu efektive aperas certagrade (versxajne gxis tia grado, kia eblas cxe artefarita idiomo) en Esperanto -- kio pruvas la genion de la originala auxtoro...

Mia konsilo al cxiu, kiuj disponas tempon aux inklinon okupigxi pri la internacilingva movado, estus: "Subtenu lojale Esperanton".

J.R.R. Tolkien

(el The British Esperantist, 1932)

(Notu: N** versxajne estas Novial)

Fonto: Tolkien en Esperanto

|

|