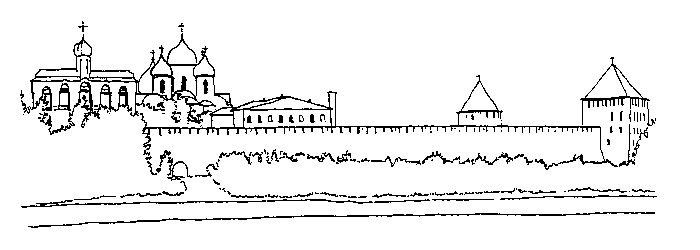

Novgorod sits astride the Volkov River, on water routes linking the Baltic to Byzantium, and to the Caspian Sea and Central Asia. Spanning the river, a single bridge connected the commercial side of town to the fortified Kremlin, or hill castle. The Kremlin included a stone citadel dating from 1044 and the Cathedral of St. Sophia. The cathedral was first built in wood in 989, at the time of the conversion, and rebuilt in stone from 1045 to 1050. (1) Both halves of the city were ringed with defensive walls-at first wood and earth palisades, but later stone-and surrounded by a flooded ditch. Six stone gates allowed access to the city. Additional defensive perimeters surrounded the city at two, seven, and twelve miles distant, using natural features and monasteries as strong points.(2)

The Rus learned to build in stone from the Byzantines. The first stone hall appeared in Kiev in 945. Typically, stone was reserved for churches. The cathedrals featured a large, high dome on piers over the central space with subsidiary cupolas on a cruciform plan surrounding it. Interiors were sumptuously decorated with mosaics, frescoes, and icons. Novgorod had a number of magnificent churches, some sponsored by merchants. Notable churches included the Cathedral of St. Nicholas, built in 1113-36 with exterior frescoes; the Cathedral of St. John built in 1127; the Church of the Assumption built in 1135-44; and beyond the town the Cathedral of the Nativity of Our Lady at the Antoniev Monastery, built 1117-19.(3) Churches were among the few buildings that had glass windows and drains. The richly decorated Cathedral of St. Sophia was famous for its bronze doors, created in Poland around 1150.

Novgorod manufactured goods for all Russia and for trade beyond its borders. Shoemakers, silversmiths, leather workers, tanners, coppersmiths, steel smelters, ironworkers, woodworkers, carpenters, turners, coopers, engravers, spoon makers, joiners, bone carvers, icon painters, spinners, weavers, bakers, cake makers, brewers, fishmongers and fish curers all plied their trade in the city. Some workshops were at home; others were located in buildings dedicated solely to that purpose.(4) Districts were sectioned off by trade, (5) while the market was centered on a plaza near the wharves on the commercial side of town.

The city was divided into five boroughs: the Slovenian, the Carpenters, the Potters, Nevorsky and Beyond the City Walls.(6) Three districts were on the Kremlin side of the river and two on the commercial side. At its height, nearly 30,000 people jammed within the city's wall. They came from all classes: courtiers, boyars, merchants, craftsmen, freemen, serfs, and slaves, as well visiting traders.

Novgorod was traversed by 9-to-14-foot wide roads paved with half logs, curved side down.(7) A rudimentary drainage system controlled the area's high water table. Sump drains constructed like bottomless barrels and sunken rooms were connected to drainage pipes. The pipes were made from hollowed-out logs and tilted to drain toward gullies and the river.(8)

Public baths of a kind, were apparently part of city life. An early traveler reported:

"[in Novgorod] I saw wooden bath houses, and they heat them fiercely, and then they undress and are naked and pour tanning fluid over themselves and take young twigs and beat themselves until they emerge half dead; and then they pour cold water over themselves and that revives them. And they do this every day; not compelled by anybody they torment themselves. And they do this in order to bathe themselves, not in order to torment themselves"(9)

Despite the attention to personal hygiene, Novgorod was still subject to uncontrollable waves of disease. In 1158, the chronicles reported a terrific plague in which men, horses, and cows died in such numbers that the bodies could not be buried for a long time and the market was unreachable due to the stench.(10)

A wooden city, Novgorod was swept by fires, much of it burning down every 20 years or so. In 1211, 15 churches and 4300 homes were burned. Quarters of the city were consumed in 1231 and 1267, while other major fires occurred in 1217, 1252, 1261, and 1275.

Novgorod was first mentioned in the chronicles in 862. It appears to have served as a fortress in the 9th and 10th centuries. By 1019 the town had a charter. In 1135 the town council asserted power over the princes. In 1200 Novgorod's army was defeated by Prince Vsevolod III of Suzdal, yet 11 years later he reconfirmed their right to select their prince. In 1215 Novgorod defeated Suzdal and asserted trade control over the Volga river. Troops from Novgorod fought through the 1200s in raids and skirmishes against Lithuanian tribes, Swedes, Germans, and other Russian cities.(11) The Mongol invasion halted some trade routes, but their hegemony made others safer (except during periods of Mongol civil wars). The city continued to prosper through the time of the Golden Horde.

(1) "Novgorod," Encyclopedia Britannica (1973) 16: 683. The term 'Lord Novgorod the Great' refers not to the great wealth and power of the city, but to its self-governance. See Section Government and Law for details.

(2) Riasanovsky, p. 89.

(3) "Novgorod," Encyclopedia Britannica (1973) 16: 683.

(4) Thompson, pp. 6, 7, 43.

(5)Society for Medieval Archaeology, p. 73.

(6)Vernadsky, Kievan Russia, p. 199.

(7) Society for Medieval Archaeology, p. 158.

(8)Thompson, p.13.

(9) Cross, p. 55.

(10) Vernadsky, Kievan Russia p. 311.

(11) Mitchell. See years 1200 to 1300.