Liancourt Rocks Bombing Range: 1947-1952

The

use of Dokdo (also known as "Liancourt Rocks" or "Takeshima") as a live bombing range took place during the

U.S. military occupation of Japan and southern Korea after the end of the

Pacific War, from 1947 to 1952. As the highest governing authority of the occupation effort, the General Headquarters of the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP) used its power to implement laws regarding military uses of land and sea-space in and around Japan and Korea, including the establishment of aerial live-fire practice ranges for the occupation forces. In order to enact these laws, SCAP issued orders to the Government of Occupied Japan in the form of "SCAPINs" (SCAP Instructions). It was in this way that SCAP established the Dokdo islets as an aerial bombing range in September 1947. Dokdo´s designation as a bombing range would have implications for those Korean seafarers who relied on the waters at and around Dokdo, and would have later implications for both the Korean and the Japanese claims of sovereignty over the island. One interesting study by two researchers of territorial cession and international treaty law, Richard W. Hartzell and Roger C. S. Lin, believe that Dokdo Island is STILL under the jurisdiction of the US military authorities.

The Dokdo Islets, also known as "Liancourt Rocks"

|

Occupation Boundaries

Under American military occupation, occupation force

boundaries were

established across Korea and Japan that separated the

areas of governing

responsibility between the different major U.S. Army

commands that made up the

occupation forces. The U.S. XXIV

Corps under the command of Army Lieutenant General

John R. Hodge was charged with

governing all of southern Korea and its various

outlying islands. Of all the islands

south of the 38th parallel known to have

originally belonged to Korea, only Dokdo Island was

not explicitly placed under the

control of the XXIV Corps. Instead,

occupation boundaries drawn up in the weeks

immediately after the Pacific War had placed

Dokdo within the Japan-based U.S. Sixth Army´s

area of responsibility, on the

Japanese side of the occupation force boundary.

Still, SCAP issued an instruction on

September 27, 1945, just weeks into the occupation of

Japan, that ordered Japanese nationals not to approach

within 12 miles of Dokdo. Within five

months, SCAP issued Instruction No. 677 which

explicitly excluded Dokdo from Japanese administrative

control, and excluded the island from the allowable

fishing areas for Japanese boats. The

occupation boundary between Korea and Japan was

thereby replaced by the so-called

´MacArthur´ line, which placed Dokdo

within the XXIV Corps´ area of responsibility,

and therefore on Korea´s side of the new

boundary line (see maps).(1)

It is important to recognize that the

boundaries were to be utilized only

for the administrative purposes of the occupation

forces. The boundaries were in no

way meant to establish either Japanese or

Korean territorial waters, fishery areas, nor were

they meant to determine the

final disposition of islands in the waters surrounding

the two countries.(2) However, it is

possible that since Dokdo was initially placed in the

area of

responsibility of occupation forces based in Japan,

the occupation authorities there might have already

made decisions to reserve the island as a bombing

range before SCAP enacted Instruction No. 677 in

January 1946, placing Dokdo on Korea´s side of

the MacArthur Line. This may explain why

decisions regarding the island´s use came from

occupation authorities in Japan, and not from the

Korea-based occupation authorities.

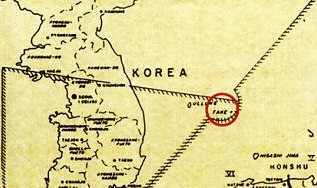

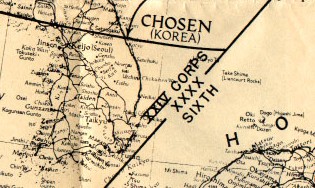

This map accompanied SCAPIN

677, which delimited the Japanese territorial sphere

to

the exclusion of Dokdo, and thereby creating the

´MacArthur Line´.

|

The initial delineation of the

occupation boundaries was drawn on this map, which was

found among a collection of the first Instructions

(SCAPINs) issued by the Supreme Commander for the

Allied Powers (SCAP) in September

1945.

|

Despite this, it is still unclear what

role

the initial occupation boundary played regarding the

island´s use as a bombing range. It

may be possible that American occupation officials

could have

been influenced by the opinions of their counterparts

in the Japanese Government

regarding the status of the island, since it is known

that Japanese officials petitioned SCAP to view

sovereignty rights over

the island in Japan´s favor from early on in the

occupation.(3) What is clear from the

documentation is that the decisions made to turn Dokdo

into a bombing range in both 1947 and 1951 came from

SCAP General Headquarters in Tokyo.

Early Gunnery and Bombing Ranges

The very first aerial ranges known to have been

established in the

sea-space around Japan during the occupation were set

up in March 1946 off the

coasts of the three main islands of

Japan. SCAPIN No. 833 informed the

Japanese Government of the three open-water

areas to be used as aerial gunnery ranges, and

instructed the Government to

"notify all Japanese agencies concerned that all

surface craft will remain out

of the areas...except when specific authority has been

granted."(4) The notification

was meant to protect fishermen, since these ranges

were

also within the authorized fishing areas that had been

allowed for Japanese

fishermen. In a similar

fashion, SCAP issued warnings when that command

designated Dokdo a bombing

range 18 months later.

In contrast to these Japanese sea ranges and the

bombing range at Dokdo, the occupation authorities in

Korea, not SCAP, established the Kimpo Air Base Air to Ground

Gunnery Range on the West Coast of Korea in the

Yellow Sea. This range, situated just nine

kilometers north of downtown Incheon on the island of

Koch´um-do, was established in June 1946.

It is not known if any warnings were issued to the

surrounding communities regarding this gunnery range,

but it is known that this range was shut down in

February 1948 due to saftey concerns involving

commercial shipping in the area and the range´s

proximity to nearby land. It is not known

if the occupation authorities in Korea issued warnings

to Korean civilians concerning either this gunnery

range or the bombing range at Dokdo.

The Designation of Dokdo as a Bombing Range and

the

Warnings Issued

Dokdo was listed as an

available "Air to Ground Target Range,"

according to USAFIK (United States Army Forces in

Korea) documents from 1948. See the whole

document.

|

As an island in a relatively isolated location in the

ocean, not known to be

inhabited, and yet close enough for U.S. air units

based in Japan, Dokdo was an

enticing choice as a bombing range for American forces

during the occupation and

Korean War period (1945-1953). The

island became an important part of US military

preparedness in the Far East soon after the US Air

Force became a separate branch of the American

military in September 1947, upon which a rotation

programme was established for its Strategic Air

Command´s (SAC) Bombardment Groups. Under

this programme, strategic bomber units based in the

United States would rotate through Kadena Air Base on

Okinawa in order to gain experience in forward

deployments, overwater flights, and bombing practice.

Dokdo was actually one of many islands in the

Pacific region that the US Air Force used as a bombing

range, particulary in training its B-29 bomber crews.

(Other islands used as bombing ranges in this

period were Farallon de Medinilla, Farallon de Pajaros

(Uracas), and the Maug Islands in the Marianas, and

Minami-Daito-jima and Oki-Daito-jima in the Ryukyus).

The first order from SCAP that designated Dokdo as an

aerial bombing range was

SCAPIN No. 1778,

issued on September 16, 1947. This

instruction, like SCAPIN No. 833, ordered Japanese

authorities to warn

their civilian populations of the presence of a danger

area at sea. SCAPIN No. 1778

mentions that American military government units and

Japanese civil authorities were ordered to warn

"inhabitants of Oki-Retto

(Oki-Gunto) and the inhabitants of all the ports on

the West Coast of the island

of Honshu north to the 38th parallel" of

Dokdo´s use as a range

prior to any live bombing exercises. (5)

SCAPIN

No. 1778 does not mention that warnings were to be

given to Korean

seafarers who visited the island, nor are there any

other communications known

to have been issued for the

purpose of warning Korean nationals of the

island´s use as a bombing range, despite the

fact that Koreans

living on Ullung Island were almost seventy kilometers

(thirty-six miles) closer

to Dokdo than the closest Japanese populations on Oki

Island. However, USAFIK (United States

Army Forces in Korea) documents

from 1948 show Dokdo to be listed as an "Air to

Ground Range" that was available to the U.S.

Fifth Air Force for use on a daily basis from 7:00am

to 5:00pm. Therefore, occupation

authorities in Korea were evidently aware of

Dokdo´s status as a bombing range, but there is

no evidence to show that even they had warned Korean

civillians of this fact.(6)

Indeed, statements

made by Gong Du-up, one of the survivors of the June 8, 1948 bombing

incident, would seem to support the idea that

Koreans had not been informed of the danger

that was present at the island. According

to his testimony, Mr. Gong

stated that he had witnessed aircraft shooting at

Dokdo days before the June 8th incident and had later

reported what

he had seen to the Ullung Island police chief, Lee

Jong-o.(7) The police chief told Mr. Gong

not to worry and that it was safe to go

back to work at Dokdo. When Mr. Gong

returned to Dokdo on June 8th to

harvest edible seaweed, the island was

bombed. The police were later not

able to give an explanation as to why the island had

been bombed. This testimony

would make it seem that authorities on Ullung Island,

who should have been made

aware of the island´s status as a bombing range,

were indeed uninformed. One central

question is still unanswered: How, and if, occupation

authorities communicated these warnings to Korean

civilians or civil authorities. In any

case, no evidence exists to show that either SCAP or

the U.S. occupation authorities in Korea had warned

Koreans of the danger posed by bombing exercises at

Dokdo. The only indication that the

occupation authorities directly warned seafarers of

the danger area at Dokdo is from a statement that Air

Force Headquarters made in Tokyo to the United Press

on June 16th, in which the Air Force said that

"vessels have been repeatedly warned to stay out

of the area since it has become an American practice

bombing run."(8) This statement still does

not make clear whether Korean seafarers and

vessels were specifically warned about the danger area

around Dokdo.

SCAPIN No. 1778 was in place at the time of the June

8, 1948 bombing, but it was quickly removed from the

list of available bombing ranges in the region.

On June 15, 1948, seven days after the

bombing, USAFIK issued an

order to stop all bombing practices at

Dokdo. By September 13th, the Far East Air

Force (FEAF) had officially and permanently closed the

bombing range at Dokdo. (9)

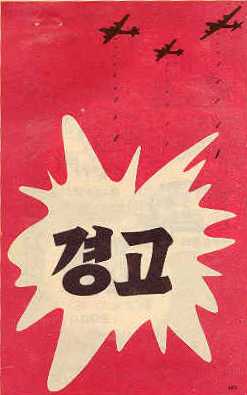

"Warning" announces this 1953 leaflet. Leaflets like this one were dropped over areas of North Korea during the Korean War to warn civilians away from areas that were to be bombed by the U.S. Air Force. It is still not known why Koreans were not warned of the danger present at Dokdo.

|

Later, during the Korean War, U.S. military authorities in Korea filed a request and received permission from the Government of the Republic of Korea (ROK) for use of the Dokdo islets as a bombing range. General John Coulter of the U.S. Eighth Army relayed this request from the U.S. Air Force to ROK Prime Minister Chang Myun on June 20, 1951. The request was for use of what he called "the Liancourt Rocks Bombing Range" for training purposes on a 24-hour basis. Coulter further stated that "the Air Force is prepared to give 15 days advance notice and to clear the area of any personnel or boats." Coulter´s mentioning of "personnel or boats" may have been a reference to the bombing of Korean boats in June 1948, and an effort to assure the ROK Government that such an incident would not be repeated. By July 1, 1951 the ROK Defense Ministry, the Ministry of Home Affairs and the Prime Minister had given their assent to the Air Force request.

Five days later, SCAP rescinded

instruction No. 1778 and issued SCAPIN No. 2160 on July 6, 1951. This new instruction from SCAP simply reasserted the island´s

designation as a bombing range. The

new SCAPIN also established new surface and air space danger areas around the

island, and again ordered that warnings be given to essentially the same

populations in Japan that had been cited in SCAPIN No. 1778.(10)

Like the previous document, SCAPIN No. 2160 included no mention of

warnings to be communicated to Korean populations, despite the fact that General Coulter had stated in his letter to the ROK Prime Minister that notice would be given to the Korean Government and the area would be cleared before actual use of the bombing range. Even though U.S. occupation authorities had been previously aware that a number of Korean fishermen had been killed in a bombing

exercise at Dokdo, that the ROK Government had received and approved a request from the U.S. Air Force, and that SCAPINs were issued making the islets a bombing range, it is not known whether warnings had been disseminated to Korean seafarers of the danger area placed around

Dokdo. In fact, there is evidence that authorities in Korea behaved as if they were unaware of Dokdo's status as a bombing range until September 1952.(11)

Restrictions Placed on Japanese

The warnings given to Japanese nationals as issued in SCAPIN Nos. 1778

and 2160 seem to have been warranted, as Dokdo was clearly a danger area. It is interesting to note however, that while SCAP warned Japanese

nationals of Dokdo´s use as a bombing range in 1947, an instruction issued a

year earlier, SCAPIN No. 1033 of June 1946, included orders that prohibited

Japanese nationals and Japanese-owned vessels from approaching within 12 miles

of Dokdo or from having any contact with the island.(12) The 12-mile restriction placed on Japanese was not rescinded until just

before the 1952 San Francisco Peace Treaty was signed between the former Allied

Powers and Japan, therefore, the restriction presumably stood for six years.(13) Thus, it is curious that SCAP would first prohibit Japanese nationals

from approaching within 12 miles of Dokdo, and then later warn them of the

island´s periodic use as a bombing range. If Japanese nationals could not be anywhere within sight distance (12

miles) of the island, then it seems reasonable to assume that they were in no

danger from any live bombing exercises taking place there. In fact, SCAPIN No. 2160 of July 1951 provided for only a five-mile

radius sea and air space off-limits area around Dokdo for safety purposes.(14) Perhaps the warning provisions in SCAPIN Nos. 1778 and 2160 were simply

meant to ensure the safety of some Japanese that might have sailed to the island

despite the restriction that had been issued in 1946. It may also be possible that the drafter(s) of SCAPIN Nos. 1778 and 2160

were unaware of the 12-mile restriction placed on Japanese nationals in the

earlier SCAPIN, No. 1033. In

any case, the restrictions and warnings that were given were completely ineffective in

preventing the tragedy that took place at Dokdo on June 8, 1948, since the

warnings were intended only for the inhabitants of Japan´s west coast and

not for the many seafarers of Korea´s east coast and Ullung Island who often

frequented Dokdo.

Japanese Government Action

As the military occupation of Japan came to an end after the signing of

the San Francisco Peace Treaty, another policy-making body in Japan chose to use

Dokdo as a bombing range. On July

26, 1952, Japanese Foreign Ministry resolution Number 34 designated the island

as a bombing range.(15) As evident

in U.S. State Department documents, U.S. officials based in Japan and the

government of Japan worked together to come to the decision. According to an October 3, 1952 memo from the U.S. Embassy in Tokyo, a

"Joint Committee" comprised of U.S. and Japanese officials that were

responsible for implementing Japanese-American security arrangements, had, in

their "selection of maneuvering areas" for military forces in Japan,

"agreed that these rocks would be designated as a facility by the Japanese

Government".(16) The memo mentions

the reasoning behind the Joint Committee´s decision and the actions that had

been taken to implement it. The

war in Korea seemed to be one of the motivating factors:

"The rocks, standing as they do in the open waters of the Japan Sea

between Korea and Japan, have a certain utility to the United Nations aircraft

returning from bombing runs in North Korean territory. They provide a radar point which will permit the dumping of unexpended

bomb loads in an identifiable area. Being

uninhabited and providing a point of navigational certainty, they are also ideal

for a live bombing target...They were turned into a bombing target, were

declared a danger area, and have been posted as out-of-bounds on a 24-hour,

7-day a week basis. Information to this effect was disseminated throughout

the Far East Command and presumably throughout the subordinate commands of the

Far East Air Force and the Naval Forces, Far East. Very recently, the information has been passed on to the

Commander-in-Chief of the Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor, in order that he may

give it formal dissemination in the form of a hydropac, or notice to

mariners."(17)

The above warnings that were given in 1952 proved to be about as

ineffective in alerting Korean nationals of the danger present at Dokdo as the

ones SCAP had issued previously. More

than a month after the announcement of the Japanese Foreign Ministry´s

resolution Number 34, the United Nations Naval Commander in Pusan (an American), not knowing that the island was a designated bombing range and

had been placed off-limits, granted permission to the Republic of Korea Navy on September 7, 1952 to allow a

300-ton Korean ship, named the Chinnamho, to travel to Dokdo on a scientific

expedition. The

expedition reported, upon safely returning, that an "unmistakably American"

aircraft dropped bombs on the island on September 15th while they were there,

forcing the expedition to cut short its activities. Such an occurrence would certainly make it seem that authorities in Korea

were neither involved in, nor even informed of the decision made by the Joint

Committee. Again, it seems unlikely that neither American nor Korean authorities in Korea were aware of any of the warnings that had been issued concerning

Dokdo. In a letter to the State Department written two weeks after the incident, the American embassy in Tokyo stated that they believed that the warnings that were in place were sufficient, and implied that authorities in Korea would be responsible for any future incidents:

"It is considered that the recent reassertion of the danger zone on these rocks should suffice to prevent the complicity of any American or United Nations Commanders in any further expeditions to the rocks which might result in injury or death to Koreans. However, owing to the crude implementation of Government controls in Korea, it is questionable that all independent Korean fishermen can be dissuaded from continuing their expeditions into these rocks."(18)

A 1,000-pound AN-M-65 General Purpose bomb photographed near the wharf at Dokdo´s East Islet in 2008. Information from the available US Air Force Documentation shows that this bomb was most likely dropped by either the 22nd Bombardment Group on March 25, 1948, or by the 93d Bombardment Group on June 8, 1948. Both units flew out of Kadena Air Base on Okinawa in 1948. As Dokdo served as a US Air Force bombing range between September 1947 and March 1953, it is possible, however, that it could have been dropped by a different Air Force unit on another occasion during this period. Dokdo´s role as a bombing range was considered an important part of the training regimen for US Air Force´s strategic bomber rotation initiative that began that year. This unexploded bomb serves as a reminder of this history, and of the lives lost in the June 8, 1948 bombing.

|

This second bombing incident at Dokdo had also caused great concern in South Korea over the territorial sovereignty of the island for the first time, and would set events in motion that would result in the end of the island´s use as a bombing range six months later.(19) By March 19,

1953, the U.S. military had officially excluded Dokdo as a practice area for American forces in the region.(20) The decision to stop using Dokdo as a bombing range seemed to be the result of a growing realization among American authorities of the possibility that the continued use of the island as a bombing range would have, in the words of American embassy personnel, "potentially explosive political implications" for the United States.(21) Embassy officials were fearful that the U.S. would be unhappily forced into choosing sides in a territorial dispute between Korea and Japan, in addition to facing possible "adverse publicity and/or legal action in the event that fishermen, who use the Island occasionally, are killed or injured by bombs."(22)

The available documentation from this time period shows that for the entire five-year period of 1947-1952, there appears to have been a failure to disseminate the warnings concerning Dokdo to the appropriate authorities and populations in the Republic of Korea. This failure seems to have been a major cause of the tragic 1948 bombing incident at Dokdo.

NEXT

WORKS CITED FOR THIS PAGE