The Forts of Verdun - Part 3

Back to Part One

Back to Part Two

Part III - Fort Vaux

In late May, the German troops could tell that something was in preparation.

Assault training increased. The ammo dumps were filling up with heavy shells, each bearing a mysterious green cross. Generals and staff officers seemed more optimistic. At the end of the month, the Kaiser himself was rumored to be near the front,

along with a large brass band.

German 210mm howitzers firing.

At the start of June the German offensive struck. It began, of course, with an artillery bombardment. But the

French noticed right away that this bombardment was different from most. The shells impacted almost silently.

The newer soldiers said "Look, the Germans are shooting duds!".

The veterans shouted "Gas!" and donned

their masks.

The "Green Cross Gas" was more technically known as phosgene.

The Germans had intended to produce a

gas which French gas masks would be ineffective against, while German

gas masks would neutralize it.

Although the French masks performed much better than the Germans hoped,

forcing virtually all the French

artillerymen into gas masks greatly reduced their effectiveness.

Hard breathing and fogged lenses didn't help

them load heavy shells or aim their weapons. The gas persisted

for two days due to a lack of wind. Sure that

phosgene would lead to victory, the Kaiser had, in fact, been near the front, planning to enter Verdun in triumph.

The plan of simply bleeding the French had, for the moment, been abandoned.

The Germans made a considerable dent in the French front southeast of Fort Douaumont on the first

day. They overran Fort Vaux, which was

externally defenseless because a "Big Bertha" round had earlier detonated a French internal demolition charge and blown out the fort's twin 75mm turret. All other weapons had been stripped off earlier in the war to supply the field army.

Nonetheless, Fort Vaux was much better prepared than Fort Douaumont

had been. Its commander was Major Raynal, who had been wounded in the leg and captured earlier in the war. Because of his wound, the Germans had exchanged him, and he had been assigned to fortress troops so he could keep off his leg much of the time. Now he was to prove that a wounded man is still very dangerous.

His garrison was nearly 300 men, armed with rifles, pistols, machine guns, and hand grenades.

The Germans occupied the counterscarp galleries and proceeded up the

communicating tunnels. The French had established blockages at these tunnels, with a machine gunner and grenadier stationed at each. Behind each blockage was constructed another, to limit the German advance at the inevitable time when the forward team should be killed. This held off the Germans for three days.

Inside Fort Vaux. One hopes the men are just sleeping.

The Germans then tried to smoke out the fort by dumping flamethrowers

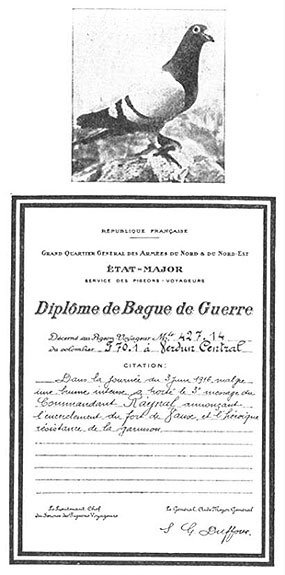

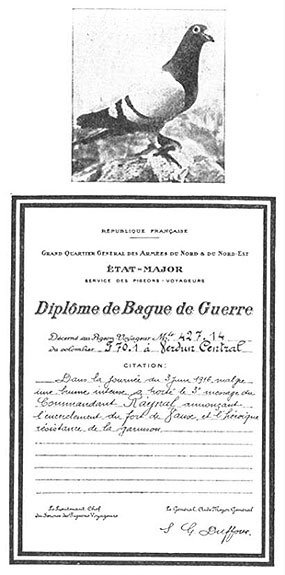

into every opening simultaneously. But the French survived. Major Raynal then sent out his last carrier

pigeon with a desperate plea for help. The bird, badly gassed, at first returned to its cage. But on the second attempt, it flew off to a command post in Verdun. After being relieved of its message, the pigeon collapsed and died. It received a posthumous Legion of Honour, and has been preserved in a museum.

Fort Vaux's last carrier pigeon.

The French made five attacks in four days to attempt to relieve Fort Vaux. But only one of these got within sight

of the fort, and was beaten back. Incredibly, a junior officer

sneaked through the lines to get word to higher

headquarters that the fort was still in French hands. More incredibly,

he returned to Fort Vaux immediately afterward.

On the second day, Fort Vaux had run out of water. Their cistern's

level gage had been stuck, and it was actually empty. By the fourth day, the French were nearly dying of thirst. Major Raynal, though it broke his heart, had to surrender. There was nothing more to do. The fort had been beaten more by thirst than by the Germans.

Part IV - Fort Douaumont (II)

The Germans' June offensive quickly stalled. Over the next few months, command changes occurred on both sides. Due to the failure of his efforts at Verdun, Falkenhayn was demoted and replaced by the Hindenburg-Ludendorff team, whose strategy was to defeat Russia first, then use manpower from that front to

defeat the French and British. General Petain was promoted to an army group command, being replaced at Verdun by General Nivelle.

Another Verdun veteran worth noting is Charles de Gaulle, who was wounded and captured as a junior officer early in the battle. He spent the rest of the war as a prisoner.

Fort Douaumont's twin to the south, Fort Moulainville, came under heavy fire from the 420's. The observers at the fort learned that it took precisely sixty-three seconds after firing

for the shells to impact. After dozens of hits, a lucky shell finally knocked out the 155mm turret. This demonstrates

the meaning of the phrase "all but impervious".

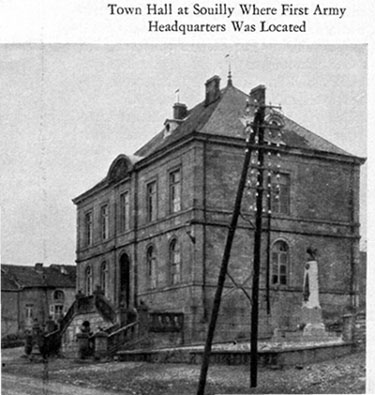

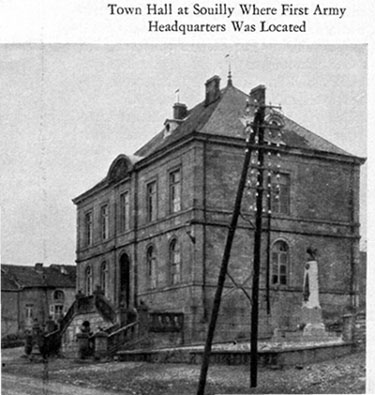

The "mairie" or town hall at Souilly near Verdun, used as a command post by General Petain, and later by General Pershing during the Meuse-Argonne offensive.

Two famous phrases that came into use during the battle bear explanation. The first is "They Shall Not Pass" (On Ne Passe Pas), which became the French motto and later served as the motto of the Maginot Line. The second is the "Sacred Way" (Voie Sacree). This is the road from Bar-Le-Duc to Verdun, which was the primary French supply line. A 24-hour endless chain of trucks was employed to keep the French forces supplied. Two divisions worked constantly to maintain the road by shovelling gravel on it. Today, each kilometer-post on the Sacred Way is in the shape of a French World War 1 monument.

The pointless bloodshed continued. On July 1st, 1916, the British and French launched the Somme Offensive, partly to relieve the pressure on Verdun. Despite a heavy artillery

preparation, the German artillery and machine guns caused 50,000 casualties (killed, wounded, prisoner) the first day. And the Allies gained little ground, even at this cost. But, at Verdun, the Germans were getting weaker, and the French were getting stronger, especially in artillery. In October of 1916, General Nivelle determined to retake Fort Douaumont.

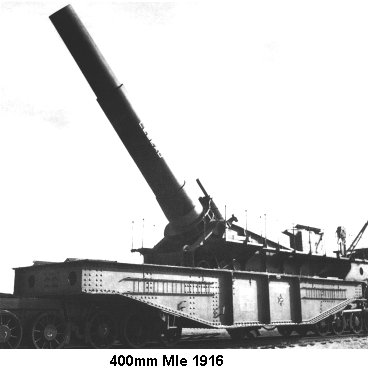

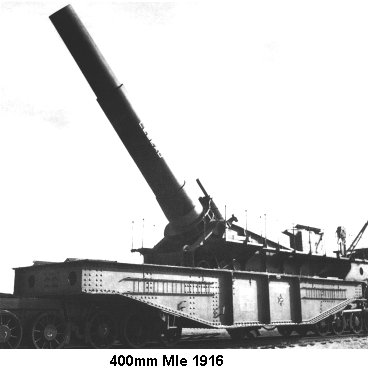

French 400mm railway howitzer.

They

had a new heavy artillery weapon, a 400mm railway howitzer, fresh from the Schneider-Creuzot works. Of higher velocity than the German 420mm, it was the most powerful weapon the Western Front had yet seen.

Moroccan troops serving in the French army. The Moroccans were tied with the Foreign Legion for receiving the most unit awards in WW1.

A battalion of tough Moroccans and a French

engineer company were assigned the supreme task of taking the fort.

They were extensively trained on a hill of the same shape as the fort, with all the important points laid out on it. The rest of the Moroccan division, and several French divisions, were also prepared for the attack.

The famous "French 75", or "Soixante-Quinze".

Nivelle made numerous tactical improvements, including burying the forward observers' telephone wires and better employment of the French army's mass of 75mm guns.

The attack jumped off on schedule. As the Moroccans approached,

the 400mm howitzer began to fire on Fort Douaumont. The first four hits were impressive, but did not penetrate.

The fifth hit cracked the concrete above the main tunnel, the first shell to ever do this to a Sere de Rivieres fort. The sixth hit was miraculous. Impacting in precisely the same spot as the fifth, it penetrated all the way down into the lower main tunnel, igniting a magazine. The fort began to fill with fumes from the burning ammunition. Even gas masks were ineffective, as

the fumes became thick enough to displace the oxygen and create a suffocating atmosphere. The Germans were forced to leave the fort. The Moroccans walked in behind them, assisted by the French engineers. A Moroccan proudly waved the French flag over the fort, signaling the other troops that it was secure.

Fort Douaumont in 1918.

The Moroccans' French battalion commander received the Legion of Honour.

Two months later, he was killed

in another attack. In the four days surrounding the capture of

Ft. Douaumont, the Moroccan battalion took 85%

casualties.

Another attack in November reclaimed Fort Vaux. An offensive

in December pushed the Germans back almost

to where they had started the battle. Marshal Joffre, commander of the

French army, was sidelined and replaced by Petain, who himself became a Marshal of France. This had been partly engineered by Andre Maginot, a member of the National Assembly.

At the start of the war Maginot had resigned his position as Assistant Secretary of War, and enlisted in the army to avoid charges of favoritism. Near Verdun in 1914 he was wounded and discharged, re-entering politics shortly thereafter, determined to correct the French army's flaws.

Thus, nearly a million dead and wounded later, Verdun ended near where

it began. Had the French given up the

position early on, it would have made little difference militarily.

There was plenty of defensible terrain to the

south and west, and their front would have been shorter. Thus,

Verdun stands out as a great waste of life with

no gain for anyone.

Part V - Denouement

Soon, General Nivelle replaced

Marshal Petain at the head of the French Army, and proposed to repeat his success at Verdun on an even larger

scale. He was convinced that he had

arrived at the formula for success in this war, and any attack that

adhered to it would be irresistible. He

proposed to attack in April 1917, at the Chemin des Dames, a long ridge

parallel to the Aisne River south of

Laon. Convinced he would succeed, he made no secret of the timing

of his attack, and took months to

prepare. But the Germans, being warned, were not idle either.

They prepared a series of trench lines that considerably shortened their front and withdrew to them, scorching the zone they had left.

The French moved up behind them, and prepared to attack as if nothing had changed. But now the French faced a stronger defensive position. In mid-April, Nivelle ordered the infantry

to attack anyway. They were slaughtered, but were still ordered

to attack each day. After about two weeks, a

regiment ordered to move to the front refused to do so. Another

regiment, ordered to move up and show the

first one an example, also refused. The spirit of mutiny spread

to whole divisions at a time. The mutiny was

suppressed with great difficulty, and a secrecy which persists to this

day. Marshal Petain was reinstated at the

head of the Army. His statement was "We must wait for the tanks,

and for the Americans".

Eventually, the Americans came. From the Aisne-Marne offensive

of June 1918, to the giant Meuse-Argonne

offensive that helped end the War on November 11, 1918, the U. S. Army dominated

the battlefield. The Americans

used primarily French artillery and supplies. The French army

played important roles in the American offensives, with simultaneous British Commonwealth offensives and the blockade of Germany all contributing to the final outcome.

In the 1920's the French and Germans effectively forgave each other.

The massive Ossuary at Douaumont was

constructed to house the remains of 150,000 unknowns of both sides.

The museum flew both French and

German flags. But the rise of Nazism overwhelmed the spirit of

collective remembrance.

In the late 20's, Andre Maginot had become the Minister of War. Having observed

the successful aspects of the forts at

Verdun, he determined to protect France, and especially the recovered

Alsace and Lorraine (where his home

village was destroyed), with the latest in fortifications. However,

he was only able to cover the area between

Switzerland and Belgium, and the Italian border, due to lack of funds

and national will on the part of others, and

his own death in 1932.

The tragedies of France's defeat in 1940, and of Marshal Petain, are beyond the scope of this piece.

Part 4

Back to Part One

Back to Part Two

Back to The Fort Page.